English Mastiff

The English Mastiff, or simply the Mastiff, is a British dog breed of very large size. It is likely descended from the ancient Alaunt and Pugnaces Britanniae, with a significant input from the Alpine Mastiff in the 19th century. Distinguished by its enormous size, massive head, short coat in a limited range of colours, and always displaying a black mask, the Mastiff is noted for its gentle and loving nature. The lineage of modern dogs can be traced back to the early 19th century, but the modern type was stabilised in the 1880s and refined since. Following a period of sharp decline, the Mastiff has increased its worldwide popularity. Throughout its history the Mastiff has contributed to the development of a number of dog breeds, some generally known as mastiff-type dogs or, confusingly, just as "mastiffs". It is the largest living canine, outweighing the wolf by up to 50 kg (110 lbs) on average.

| Mastiff | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

A Mastiff | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other names | Mastiff | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Origin | England | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dog (domestic dog) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Appearance

With a massive body, broad skull and head of generally square appearance, it is the largest dog breed in terms of mass. It is on average slightly heavier than the Saint Bernard, although there is a considerable mass overlap between these two breeds. Though the Irish Wolfhound and Great Dane can be more than six inches taller, they are not nearly as robust.[1]

The body is large with great depth and breadth, especially between the forelegs—which causes these to be set wide apart. The length of the body taken from the point of the shoulder to the point of the buttock is greater than the height at the withers. The AKC standard height (per their website) for this breed is 30 inches (76 cm) at the shoulder for males and 27.5 inches (70 cm) (minimum) at the shoulder for females. A typical male can weigh 150–250 pounds (68–113 kg), a typical female can weigh 120–200 pounds (54–91 kg), with very large individuals reaching 300 pounds (140 kg) or more.

Coat colour standards

The former standard specified the coat should be short and close-lying. Long-haired Mastiffs, known as "Fluffies", are caused by a recessive gene — they are occasionally seen. The AKC considers a long coat a fault but not cause for disqualification. English Mastiff colours are apricot-fawn, silver-fawn, fawn, or dark fawn-brindle, always with black on the muzzle, ears, and nose and around the eyes.

The colours of the Mastiff coat are differently described by various kennel clubs, but are essentially fawn or apricot, or those colours as a base for black brindle. A black mask should occur in all cases. The fawn is generally a light "silver" shade, but may range up to a golden yellow. The apricot may be a slightly reddish hue up to a deep, rich red. The brindle markings should ideally be heavy, even and clear stripes, but may actually be light, uneven, patchy, faint or muddled. Piebald Mastiffs occur rarely. Other non-standard colours include black, blue brindle, and chocolate (brown) mask. Some Mastiffs have a heavy shading caused by dark hairs throughout the coat or primarily on the back and shoulders. This is not generally considered a fault. Brindle is dominant over solid colour, other than black, which may no longer exist as a Mastiff colour. Apricot is dominant over fawn, though that dominance may be incomplete. Most of the colour faults are recessive, though black is so rare in the Mastiff that it has never been determined whether the allele is recessive or a mutation that is dominant.[2]

The genetic basis for the variability of coat in dogs has been much studied, but all the issues have not yet been resolved.[3] On the basis of what is known (and remembering that, as dogs are diploid animals, each gene location (locus) appears twice in every animal, so questions of dominance also must be resolved), the gene possibilities allowed by the Mastiff standard are AyBDEmh(kbr_or_ky)mS. This describes a dog which is fawn with a dark nose, non-dilute, black-masked, non-harlequin, brindled or not brindled, non-merle, and non-spotted. To allow for the rare exceptions we must include "b" (brown mask and possible brown brindling), "d" (blue mask and possible blue brindling), "sp" (pied spotting), and perhaps "a" (recessive black). The possible combination of homozygous brown and homozygous blue is a pale brown referred to as Isabella in breeds where it is relatively common. On a Mastiff, this would appear on mask, ears, and any brindling that was present. Speculative gene locations may also exist, so a Mastiff may be "I" (apricot) or "i" (non-apricot) and perhaps "cch" (silver lightening) or "C" (without silver lightening).[4] (Note that this "C locus" may not be the same as the one identified in other animals, SLC45A2.)

Record size

The greatest weight ever recorded for a dog, 343 pounds (155.6 kg), was that of an English Mastiff from England named Aicama Zorba of La Susa, although claims of larger dogs, including Saint Bernards, Tibetan Mastiffs, and Caucasian ovcharkas exist.[5] According to the 1989 edition of the Guinness Book of Records, in March 1989, when he was 7 years old, Zorba stood 37 inches (94 cm) at the shoulder and was 8 ft 3 in (251 cm) from the tip of his nose to the tip of his tail, about the size of a small donkey.[6] After 2000, the Guinness Book of World Records stopped accepting largest or heaviest pet records.[7]

Temperament

The Mastiff breed has a desired temperament, which is reflected in all formal standards and historical descriptions. Sydenham Edwards wrote in 1800 in the Cynographia Britannica:

What the Lion is to the Cat the Mastiff is to the Dog, the noblest of the family; he stands alone, and all others sink before him. His courage does not exceed his temper and generosity, and in attachment he equals the kindest of his race. His docility is perfect; the teazing of the smaller kinds will hardly provoke him to resent, and I have seen him down with his paw the Terrier or cur that has bit him, without offering further injury. In a family he will permit the children to play with him, and suffer all their little pranks without offence. The blind ferocity of the Bull Dog will often wound the hand of the master who assists him to combat, but the Mastiff distinguishes perfectly, enters the field with temper, and engages in the attack as if confident of success: if he overpowers, or is beaten, his master may take him immediately in his arms and fear nothing. This ancient and faithful domestic, the pride of our island, uniting the useful, the brave and the docile, though sought by foreign nations and perpetuated on the continent, is nearly extinct where he probably was an aborigine, or is bastardized by numberless crosses, everyone of which degenerate from the invaluable character of the parent, who was deemed worthy to enter the Roman amphitheatre, and, in the presence of the masters of the worlds, encounter the pard, and assail even the lord of the savage tribes, whose courage was sublimed by torrid suns, and found none gallant enough to oppose him on the deserts of Zaara or the plains of Numidia.[8]

The American Kennel Club sums up the Mastiff breed as:

- a combination of grandeur and good nature as well as courage and docility. Domesticated Mastiffs are powerful yet gentle and loyal dogs, but due to their physical size and need for space, are best suited for country or suburban life.[9]

Health

At all stages of development, the Mastiff should show the breed characteristics of massiveness and sound, if cumbersome, movement. The Mastiff is a particularly large dog demanding correct diet and exercise. Excessive running is not recommended for the first 2 years of the dog's life, in order not to damage the growth plates in the joints of this heavy and fast-growing dog, which in some weeks may gain over 5 lb. However, regular exercise must be maintained throughout the dog's life to discourage slothful behaviour and to prevent a number of health problems. A soft surface is recommended for the dog to sleep on to prevent the development of calluses, arthritis, and hygroma (an acute inflammatory swelling). Due to the breed's large size, puppies may potentially be smothered or crushed by the mother during nursing. A whelping box, along with careful monitoring, can prevent such accidents. The average lifespan of the Mastiff is about 7 years, although it is not uncommon for some to live 10–13 years, and there are records of a female named Kush making it to an age of 15.[10][11] [12]

Major problems can include hip dysplasia and gastric torsion. Other problems include obesity, osteosarcoma, and cystinuria. Problems only occasionally found include cardiomyopathy, allergies, vaginal hyperplasia, cruciate ligament rupture, hypothyroidism, OCD, entropion, progressive retinal atrophy (PRA), and persistent pupillary membranes (PPM).

When purchasing a purebred Mastiff, experts often suggest that the dog undergo tests for hip dysplasia, elbow dysplasia, thyroid, and DNA for PRA.

A Mastiff may be kept in an apartment, but care must be taken to give it enough exercise. Mastiffs should be fed two or three times a day; it is believed that one large meal per day can increase the chance of gastric torsion.[13]

History

From ancient times to the early 19th century

There is a ceramic and paint sculpture of a mastiff-like dog from Mesopotamia region during the Kassite period (mid-2nd millennium B.C.).[14]

These dogs may be related to the dogs that fought lions, tigers, bears, and gladiators in Roman arenas.[15] Certainly an element in the formation of the English Mastiff was the Pugnaces Britanniae that existed at the time of the Roman conquest of Britain. The ancient Roman poet Grattius (or Grattius Faliscus) wrote of British dogs, describing them as superior to the ancient Greek Molossus, saying:

What if you choose to penetrate even among the Britons? How great your reward, how great your gain beyond any outlays! If you are not bent on looks and deceptive graces (this is the one defect of the British whelps), at any rate when serious work has come, when bravery must be shown, and the impetuous War-god calls in the utmost hazard, then you could not admire the renowned Molossians so much.[16]

The turn-of-the-millennium Greek historian Strabo reported that dogs were exported from Britain for the purpose of game hunting, and that these dogs were also used by the Celts as war dogs.[17] As far as the origin of the Pugnaces Britanniae is concerned, there is unproven speculation that they were descended from dogs brought to Britain by the Phoenicians in the 6th century BC.[18][19][20] This breed's first written accounts in England date back to 55 BC when Caesar noted them during his invasions. Many were sent to Italy and in the Roman Empire they became fighting dogs.[20]

The Alaunt is likely to have been another genetic predecessor to the English Mastiff. Introduced by the Normans, these dogs were developed by the Alans, who had migrated into France (then known as Gaul) due to pressure by the Huns at the start of the 5th century. Intriguingly they were known from the Romans to live in a region (the Pontic-Caspian Steppe) about 700 km to the north of the region where the Assyrians once lived. Again, any canine connections are speculative.[21]

The linguistic origin of the name "Mastiff" is unclear. Many claim that it evolved from the Anglo-Saxon word "masty", meaning "powerful".[22] Other sources, such as the Oxford English Dictionary, say the word originated from the Old French word mastin (Modern French mâtin), the word being itself derived from Vulgar Latin *ma(n)suetinus "tame", see Classical Latin mansuetus with same meaning. The first list of dog breed names in the English language, contained within The Book of Saint Albans, published in 1465, includes "Mastiff ".[23] This work is attributed to Prioress Juliana Berners, but in part may be translated from the early 14th century Norman-French work Le Art de Venerie, by Edward II's Huntmaster Guillaume Twici.[24]

In 1570, Conrad Heresbach, in Rei Rusticae Libri Quatuor, referred to "the Mastie that keepeth the house".[25] Heresbach was writing in Latin; his work was translated a few years later into English by Barnabe Googe as Foure Bookes of Husbandrie.[26] This work was originally adapted from De Re Rustica by 1st century Roman writer Columella, which highlights the Roman connection. Certainly from Roman to medieval times, Mastiff-like dogs were used in the blood sports of bull-baiting, bear-baiting, lion-baiting, and dog fighting, as well as for hunting and guarding.

Dogs known as Bandogs, who were tied (bound) close to houses, were of the Mastiff type.

They were described by John Caius[27] in 1570 as vast, huge, stubborn, ugly, and eager, of a heavy and burdensome body—noted for their use as guard dogs on remote estates.

The naturalist Christopher Merret in his 1666 work Pinax Rerum Naturalium Brittanicarum has a list of British mammals, including 15 kinds of dog, one of which is "Molossus, Canis bellicosus Anglicus, a Mastif".[28] Literally, "Molossus, warlike English dog, a Mastiff", and perhaps the first conflation of the breeds Molossus and Mastiff.

When in 1415 Sir Peers Legh was wounded in the Battle of Agincourt, his Mastiff stood over and protected him for many hours through the battle. The Mastiff was later returned to Legh's home and was the foundation of the Lyme Hall Mastiffs. Five centuries later this pedigree figured prominently in founding the modern breed.[29] Other aristocratic seats where Mastiffs are known to have been kept are Elvaston Castle (Charles Stanhope, 4th Earl of Harrington and his ancestors) and Chatsworth House. The owner of the Chatsworth Mastiffs (which were said to be of Alpine Mastiff stock) was William Cavendish, 5th Duke of Devonshire, known to his family as Canis.[30] Mastiffs were also kept at Hadzor Hall, owned by members of the Galton family, famous for industrialists and scientists, including Charles Darwin. Some evidence exists that the Mastiff first came to America on the Mayflower, but the breed's further documented entry to America did not occur until the late 19th century.

From the early 19th century to World War I

In 1835, the Parliament of the United Kingdom implemented an Act called the Cruelty to Animals Act 1835, which prohibited the baiting of animals. This may have led to decline in the aggressive Mastiffs used for this purpose, but Mastiffs continued to be used as guards for country estates and town businesses.

Systematic breeding began in the 19th century,[31] when J.W. (John Wigglesworth) Thompson purchased a bitch, Dorah, from John Crabtree, the head gamekeeper of Kirklees Hall, whose dogs were often held in the name of his employer, Sir George Armitage. Dorah was descended in part from animals owned by Thompson's grandfather Commissioner Thompson at the beginning of the century, as well as a Mastiff of the Bold Hall line (recorded from 1705), a bitch purchased from canal boat men, another caught by Crabtree in a fox trap, a dog from Nostal priory and another dog from Walton Hall, owned by the naturalist, Charles Waterton. J. W. Thompson's first stud dog, Hector, came from crossing a bitch, Juno, bought from animal dealer Bill George, to a dog, Tiger, owned by a Captain Fenton. Neither of these had any pedigree, as was normal for the period. Between 1830 and 1850 he bred the descendants of these dogs and some others to produce a line with the short, broad head and massive build he favoured. In 1835, T.V.H. Lukey started his operations by breeding an Alpine Mastiff bitch of the Chatsworth line, Old Bob-Tailed Countess (bought from dog dealer Bill White), to Pluto, a large black Mastiff of unknown origin belonging to the Marquis of Hertford. The result was a bitch called Yarrow, who was mated to Couchez, another Alpine Mastiff belonging (at the time) to White and later mated to a brindle dog also in White's possession. Lukey produced animals that were taller but less massive than Thompson's. After 1850, Thompson and Lukey collaborated, and the modern Mastiff was created, though animals without pedigree or of dubious pedigree continued to be bred from into the 20th century.

Another important contribution to the breed was made by a dog called Lion, owned by Captain (later Colonel) John Garnier of The Royal Engineers.[32] He bought two Mastiffs from the previously mentioned dealer Bill George. The bitch, Eve, bought by George at Leadenhall Market, was old enough to be grey-muzzled, but of good type. The dog, Adam, was of reputed Lyme Hall origin, but bought at Tattersalls and suspected by Garnier of containing a "dash of Boarhound", an ancestral form of Great Dane. Garnier took them with him when he was posted to Canada and brought back their puppy, Lion. He was bred to Lukey's Countess to produce Governor, the source of all existing male Mastiff lines (Lion was also mated to Lufra, a Scottish Deerhound, and their puppy Marquis appears in the pedigrees of both Deerhounds and Irish Wolfhounds).

.jpg.webp)

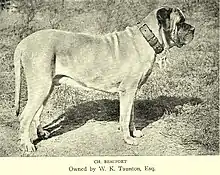

In the 1880s soundness was sacrificed for type, which was widely attributed to the short-headed, massive, but straight-stifled and chocolate-masked Ch. Crown Prince. This dog dominated all of his contemporaries in terms of the number of offspring. Subsequently, the Mastiff lost popularity but gained a consistency of type, with leaner, longer-headed specimens becoming relatively less common.

Prominent among the breeders of this era who began to restore soundness were Edgar Hanbury and his relation, the politician and philanthropist Mark Hanbury Beaufoy, later Chairman of The Kennel Club, who reaching his peak as a breeder with the Crown Prince grandson, Ch. Beaufort, eventually exported to America.

AKC recognition occurred in 1885.[20] Despite such imports, Mastiff numbers in the US declined steadily through the 1890s and the early 20th century. From 1906 to 1918, only 24 Mastiffs were registered in the United States. After 1910, none of these were bred in America. By the time World War I ended, other than a few exports to North America, the breed was extinct outside of Great Britain.

After World War I

In 1918, a dog called Beowulf, bred in Canada from British imports Priam of Wingfied and Parkgate Duchess, was registered by the American Kennel Club, starting a slow re-establishment of the breed in North America. Priam and Duchess, along with fellow imports Ch Weland, Thor of the Isles, Caractacus of Hellingly and Brutus of Saxondale, ultimately contributed a total of only two descendants who would produce further offspring: Buster of Saxondale and Buddy. There were, however, a number of other imports in the period between the wars and in the early days of the Second World War Those who can still be found in modern pedigrees were 12 in number,[33] meaning the North American contribution to the gene pool after 1945 (including Buster and Buddy) consisted of 14 Mastiffs.

In the British Isles during World War II, virtually all Mastiff breeding stopped due to the rationing of meat. After the war, such puppies as were produced mostly succumbed to canine distemper, for which no vaccine was developed until 1950.[34] Only a single bitch puppy produced by the elderly stock that survived the war reached maturity, Nydia of Frithend. Her sire had to be declared a Mastiff by the Kennel Club, as his parentage was unknown, and he was thought by some to be a Bullmastiff.

After the war, animals from North America (predominantly from Canada) were imported into Britain. Therefore, all Mastiffs in the late 1950s were descended from Nydia and the 14 Mastiffs previously mentioned, with each all-male bloodline going back to Ch. Crown Prince. It has been alleged that the Mastiff was bred with other more numerically significant giant breeds, such as Bullmastiffs and St. Bernards, with the justification that these were considered close relatives to the Mastiff. In 1959, a Dogue de Bordeaux, Fidelle de Fenelon, was imported from France to the U.S., registered as a Mastiff, and became the 16th animal in the post-war gene pool.[35] Since that time, the breed has gradually been restored in Great Britain, has reached the 28th most popular breed in the U.S.,[36] and is now found worldwide.

Famous English Mastiffs

- "Carlo" from "The Adventure of the Copper Beeches", a Sherlock Holmes short story by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle[37]

- "Crown Prince", progenitor of the modern breed, owned by psychiatrist L. Forbes Winslow[31]

- "Chupadogra" (a.k.a. "Buster") is an elderly English Mastiff, voiced by Sam Elliott in the 2010 film Marmaduke.[38]

- "Hercules" (a.k.a. "the Beast"), from the film The Sandlot[39]

- "Goliath" (a.k.a. "the Great Fear"), from the film The Sandlot 2[40]

- "Keeper", Old English Mastiff known as "the keeper's night-dog.[41]

- "Lady Marton", owned by Victorian industrialist Henry Bolckow, and claimed by some to have been a St. Bernard[31]

- "Lenny" is a brindle English Mastiff from the 2009 movie Hotel for Dogs[42]

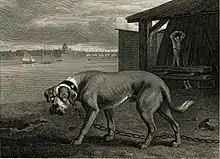

- "Leo", owned by Richard Ansdell, RA, and the model for his painting "The Poacher", a.k.a. "The Poacher at Bay"[31]

- "Mason the Mastiff", in the 2007 film Transformers[43]

- "Moss" and "Jaguar", of the Japanese series Ginga: Nagareboshi Gin and its sequel Ginga Densetsu Weed[44]

- "Mudge" – Henry and Mudge (children's books)[45][46]

- "Old Major", owned by Joseph Smith, Jr. After his death, owned by his son Joseph Smith III. [47]

- "Zorba", officially recognised as the world's longest and heaviest dog.[48]

See also

References

- "The Biggest Dog Breed". Bigpawsonly.com. Archived from the original on 25 July 2013. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- Clarence C. Little, The Inheritance of Coat Color in Dogs, Howell Book House, 1957

- "Dog Coat Color Genetics". Homepage.usask.ca. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- Sheila M. Schmutz (27 December 2008). "Coat Color Alleles in Dogs". Retrieved 12 September 2010

- Guinness World Records 2000 – Millennium edition, Pg 106, Guinness World Records Ltd., 2000, ISBN 0-85112-098-9

- "Breeds of Livestock – Miniature Donkey". Ansi.okstate.edu. Archived from the original on 31 October 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- "Frequently Asked Questions". Guinness World Records. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- Sydenham EdwardsCynographia Britannica, 1800 London: C. Whittingham

- "American Kennel Club – Mastiff". The American Kennel Club. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- "Health Survey Statistics". Mastiff Club of America. Archived from the original on 23 June 2017. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- O'Neill, D. G.; Church, D. B.; McGreevy, P. D.; Thomson, P. C.; Brodbelt, D. C. (2013). "Longevity and mortality of owned dogs in England" (PDF). The Veterinary Journal. 198 (#3): 638–43. doi:10.1016/j.tvjl.2013.09.020. PMID 24206631."n=35 median=7.1 IQR=2.01–9.01"

- "What You Need to Know About the Old English Mastiff". 6 December 2020.

- "Gastric Torsion in Dogs - Vet Help Direct". 16 March 2011.

- "Mastiff". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Gallery 406

- mastiff. Britannica Concise Encyclopedia. Chicago, 2012. Accessed 3 October 2013.

- "Grattius – Cynegeticon". Retrieved 7 June 2009.

- "Strabo's Geography". Retrieved 7 June 2009.

- Leighton, R. (1907). The New Book of the Dog. Cassell.

- Pugnetti, Gino (1980). Simon & Schuster's guide to dogs. Schuler, Elizabeth Meriwether. New York: Simon and Schuster. pp. 58. ISBN 0671255266. OCLC 6200215.

- Bell, Jerold (2012). Veterinary medical guide to dog and cat breeds. Kathleen Cavanagh,Larry Tilley, Francis W. K. Smith. Jackson, WY: CRC Press. pp. 309–311. ISBN 9781482241419. OCLC 878262855.

- Hancock, David (2001). The Mastiffs: The Big Game Hunters

- "Mastiff Breed Standard – Club – Old English Mastiff Club". Mastiffclub.com. Archived from the original on 29 January 2018. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- "The history of the dog in Britain".

- Twiti, William. The Art of Hunting translator/editor Danielson, B.. Cynegetica Anglica 1. Stockholm Studies in English XXXVII. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell Int. 1977.

- Andersson, D. D. (1999). The Mastiff: Aristocratic Guardian. Doral Publishing. ISBN 978-0-944875-51-3

- Foure bookes of husbandrie, collected by M. Conradus Heresbachius, councellour to the high and mightie prince, the Duke of Cleue: containing the whole art and trade of husbandry, gardening, graffing, and planting, with the antiquitie, and commendation thereof. Newly Englished, and increased by Barnabe Googe, Esquire, Conrad Heresbach, [Rei rusticae libri quatuor. English] London : Printed by T. Este, for Thomas Wight, 1596

- "BC Museum: Caius". Gis.net. 18 August 2010. Archived from the original on 30 November 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- Ford, E. B. (1977) [1945]. Butterflies. Collins (New Naturalist).

- Homan, M. (2000). A Complete History of Fighting Dogs (Pg.10) Howell Book House Inc. ISBN 1-58245-128-1

- "Regency Personalities – Georgiana – Duchess of Devonshire". Homepages.ihug.co.nz. Archived from the original on 28 February 2018. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- The History of the Mastiff, M. B. Wynn 1885. William Loxley.

- "The chronicles of the Garniers of Hampshire during four centuries, 1530–1900" (https://archive.org/stream/chroniclesofgarn00garn/chroniclesofgarn00garn_djvu.txt)

- (1) Roxbury Boy, (2) Millfold Lass, (3) Buzzard Pride (survived only by Merle's Brunhilda of Lyme Hall, who was in turn survived only by Shanno of Lyme Hall), (4) Gyn of Hammercliffe, (5) Duke of Hellingly, (6) Kathleen of Hellingly, (7) King of Hellingly (survived only by Eric of Altnacraig), (8) Maude of Hellingly, (9) Crusader of Goring (survived only by Blythe of Hampden), (10) Goldhawk Elsie, (11) Broomcourt Nell, (12) Rolanda, The History & Management of the Mastiff, Author(s): Baxter, Elizabeth J; Hoffman, Patricia B., Dogwise 2004

- Pomeroy, L.W.; Bjørnstad, O.N; Holmes, E.C. (2008). "The Evolutionary and Epidemiological Dynamics of the Paramyxoviridae". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 66 (#2): 98–106. Bibcode:2008JMolE..66...98P. doi:10.1007/s00239-007-9040-x. PMC 3334863. PMID 18217182.

- The History & Management of the Mastiff, Author(s): Baxter, Elizabeth J; Hoffman, Patricia B., Dogwise 2004 ISBN 1-929242-11-5

- "AKC Dog Registration Statistics". Akc.org. Archived from the original on 16 July 2007. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- "Adventure 12: "The Adventure of the Copper Beeches" - The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes - Lit2Go ETC". Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. 18 August 2022. Retrieved 18 August 2022.

- "Marmaduke - Full Cast & Crew". TVGuide.com. 27 May 2010. Retrieved 18 August 2022.

- ""The Sandlot Dog" | Modern Molosser". www.modernmolosser.com. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- "Sandlot 2, The". Humane Hollywood. 14 February 2020. Retrieved 18 August 2022.

- Morrow, L.B. (2012). The Giant Book of Dog Names. Gallery Books. p. 228. ISBN 978-1-4516-6690-8. Retrieved 18 August 2022.

- Morgenstern, Joe (17 January 2009). "'Hotel for Dogs' Is Puppy Chow". WSJ. Retrieved 18 August 2022.

- "AT HOME WITH: Michael Bay; A Slam-Bang Master With a House of Om - The New York Times". The New York Times. 17 July 2003. Archived from the original on 29 July 2022. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- "Ginga Nagareboshi Gin (TV)". Anime News Network. 18 August 2022. Retrieved 18 August 2022.

- "ReadWriteThink: Lesson Plan: Word Study With Henry and Mudge". Archived from the original on 3 January 2010. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- "Henry and Mudge". Archived from the original on 31 May 2008. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- "Episode 85: Old Major - Alexander Baugh". LDS Perspectives Podcast. 27 June 2018.

- "Meet the world's biggest pets". MSN. Retrieved 23 January 2019.