Environmental sensitivity

Environmental sensitivity describes the ability of an individual to perceive and process information about their environment.[1][2][3] It is a basic trait found in many organisms that enables an individual to adapt to different environmental conditions. Levels of Environmental Sensitivity often vary considerably from individual to individual, with some being more and others less sensitive to the same conditions. Such differences have been observed across many species such as pumpkinseed fish, zebra finches, mice, non-human primates and humans, indicating that there is a biological basis to differences in sensitivity.

Theoretical background

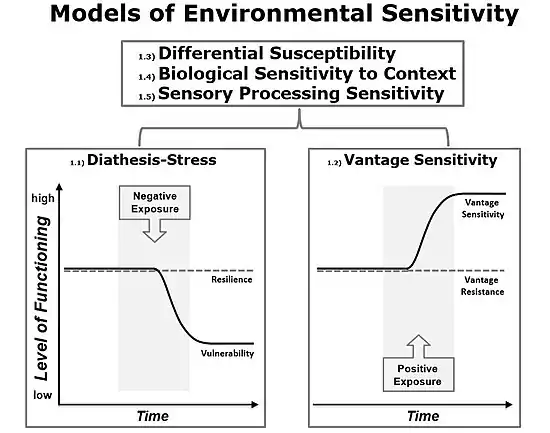

The concept of Environmental Sensitivity integrates multiple theories on how people respond to negative and positive experiences. These include the frameworks of Diathesis-stress model[4] and Vantage Sensitivity,[5] as well as the three leading theories on more general sensitivity: Differential Susceptibility,[6][7] Biological Sensitivity to Context,[8] and Sensory processing sensitivity[9] (see Figure 1 for an illustration of the different models). These will be described briefly in turn, before presenting the integrative theory of Environmental Sensitivity in more detail.[1]

Diathesis-stress

According to the long-standing Diathesis-stress model, people differ in their response to adverse experiences and environments, with some individuals more negatively affected by environmental stressors than others.[4] The model proposes that such differences in response result from the presence of "vulnerability" factors, which include psychological (e.g., impulsive personality), physiological (e.g., high physiological reactivity) and genetic factors (e.g., genetic variation in the serotonin transporter [5-HTTLPR short allele]). In other words, the model suggests that individuals carrying certain vulnerability factors are at greater risk of developing problems when exposed to adverse environments. While the Diathesis-stress model is helpful in understanding differences in response to negative stressors, it does not consider or describe differences in response to positive experiences.

Vantage sensitivity

The vantage sensitivity framework was developed in 2013 by Michael Pluess and Jay Belsky to describe individual differences in response to positive experiences and environments. While some people appear to benefit particularly strongly from positive experiences (e.g., positive parenting, supportive relationships, psychological interventions), others appear to benefit less.[5] Although a relatively new concept, a growing number of studies provides evidence to support the framework. While the Vantage Sensitivity framework considers individual differences in response to positive experiences, it does not make predictions about the response to negative experiences.

Differential susceptibility

Differential susceptibility, proposed by Jay Belsky, brings the differential responses to both positive and negative experiences together in one single model. Grounded in evolutionary theory, Belsky and colleagues sought to understand why and how children differ so fundamentally in their developmental response to external influences, with some being more and others less susceptible.[6][7] Importantly, the theory finds that more susceptible individuals are not only more negatively affected by adverse experiences (as described in the Diathesis-stress model) but also particularly positively affected by the presence of favourable conditions (as described in the Vantage Sensitivity model). According to empirical studies, Differential Susceptibility is associated with various genetic, physiological and psychological factors, some of which are described below (see Empirical Evidence). Although early research suggested that differences in individuals' susceptibility are rooted in genetic factors, more recent research has shown that susceptibility is also influenced by prenatal and early postnatal environmental factors.

Biological Sensitivity to Context

The theory of Biological Sensitivity to Context by Tom Boyce and Bruce Ellis is based on evolutionary thinking and proposes that an individual's sensitivity to the environment is shaped by the quality of early life experiences.[8] For example, particularly negative or especially positive childhood environments are understood to predict greater physiological reactivity later in life. In contrast, sensitivity is expected to be lowest for individuals with childhood environments that were neither extremely beneficial nor extremely adverse.

Sensory processing sensitivity

Sensory processing sensitivity (SPS) theory by Elaine N. Aron and Arthur Aron proposes that sensitivity is a stable human trait characterized by greater awareness of sensory stimulation, behavioural inhibition, deeper cognitive processing of environmental stimuli, and higher emotional and physiological reactivity.[9] According to this theory, approximately 20% of people fall into the category of a Highly Sensitive Person (HSP), in contrast to the remaining 80% who are considered less sensitive. Furthermore, the theory suggests that the sensitivity trait is adaptive from an evolutionary perspective, and regards differences in sensitivity as genetically determined and expressed via a more sensitive central nervous system.

Environmental sensitivity

The broad theory of Environmental sensitivity.[1] integrates all of the listed frameworks and proposes that although all people are sensitive to their environment, some individuals tend to be more sensitive than others. Furthermore, the theory of Environmental Sensitivity suggests that people vary in their sensitivity to the environment due to differences in their ability to perceive and process information about the environment. In other words, more sensitive individuals are characterised by heightened perception as well as deeper processing of external information due to neurobiological differences in the central nervous system, which are influenced by genetic as well as environmental factors. The integrative perspective of Environmental sensitivity further proposes that whilst some individuals are more sensitive to both negative and positive experiences, others may be particularly vulnerable to adverse experiences (but not very sensitive to positive ones), whilst some may be especially responsive to positive exposure (but not vulnerable to negative ones).

Empirical evidence for individual differences in sensitivity

Differences in sensitivity have been studied in relation to a wide range of sensitivity markers, such as genetic, physiological and psychological ones. These are now discussed in turn.

Genetic markers of sensitivity

A growing number of studies provide empirical evidence to support individual differences in sensitivity at the genetic level. These include traditional Gene-environment interaction studies featuring Candidate genes,[10][11] as well as more recent genome-wide approaches.[12] As an example for the latter, Keers et al.[13] created a polygenic score for Environmental Sensitivity based on about 25,000 gene variants across the genome and then tested whether children at the extremes of this spectrum of genetic sensitivity differed in their response to the parenting quality they received. According to the results, children with high genetic sensitivity were more likely to develop emotional problems when experiencing negative parenting but also less likely to develop problems when parenting was positive. On the other hand, children with low genetic sensitivity were not as impacted by the experience of negative or positive parenting, and did not differ from each other in emotional problems based on parenting quality. Hence, this study provides important evidence that genetic sensitivity, measured across the genome, predicts children's sensitivity to both negative and positive environmental influences.

Physiological markers of sensitivity

Several empirical studies have reported differences in sensitivity to the environment in relation to individuals' physiological reactivity. Higher reactivity generally appears to reflect greater sensitivity. For example, research has shown that children with a higher physiological response to stress (indicated by the hormone cortisol) are more strongly affected by their family's financial situation.[14] More specifically, a high cortisol response in children was associated with more positive cognitive development when family income was high, but with reduced cognitive development when family income was low. In contrast, family income was less relevant for the cognitive development of children who displayed low physiological reactivity (i.e., a low cortisol response). Similarly, adolescents with high cortisol levels have been found to report more stress when experiencing school-related challenges but also the lowest stress in less demanding situations, whereas adolescents with lower cortisol levels were generally less affected by either low or high school-related challenges [15]

Psychological markers of sensitivity

The majority of evidence for individual differences in sensitivity due to psychological markers of sensitivity is based on studies that investigate the interplay between infant temperament and parenting during childhood. Generally, higher fearfulness, fussiness, and negative emotionality in infancy have been associated with greater sensitivity to parenting quality. According to a large meta-analysis which summarises the findings from 84 individual studies, children that are characterised by a more sensitive temperament were more strongly affected by the parenting they receive.[16] More specifically, sensitive children were more likely to develop problems when experiencing harsh and punitive parenting but also least likely to have problems when they were raised in emotionally warm and caring environments. Less sensitive children, on the other hand, did not differ much from each other whether they received more negative or more positive parenting.

Determinants of Environmental Sensitivity

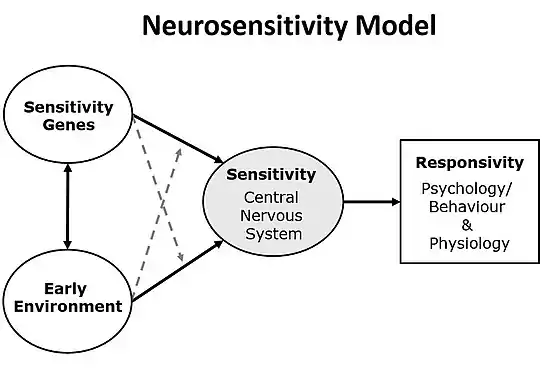

An individual's level of Environmental Sensitivity is the result of a complex interplay between genes and environmental influences across development.[1] Empirical studies suggest that genetic influences are important for the development of the trait, but only about 50% of the differences in sensitivity between people can be explained by genetic factors, with the remaining 50% being shaped by environmental influences (see Figure 2). Furthermore, the genetic component of sensitivity is most likely made up by a large number of genetic variants across the whole genome, each making a small contribution, rather than a few specific genes. Importantly, although sensitivity has a substantial genetic basis, it may be the quality of the environment when growing up that shapes this genetic potential for sensitivity further. For example, those carrying a larger number of sensitivity genes may develop a sensitivity that is more geared towards threat when growing up in a challenging or adverse environment (i.e., vulnerability as described in the Diathesis-Stress model), whereas those growing up in a predominately supportive and secure context may develop heightened sensitivity towards positive aspects of the environment (i.e., Vantage Sensitivity). Similarly, those that experienced similar levels of both negative and positive exposures during childhood may develop equal levels of sensitivity to negative and positive experiences (i.e., Differential Susceptibility).

Underlying biological mechanisms of Environmental Sensitivity

Environmental Sensitivity proposes that sensitivity is driven primarily by a heightened sensitivity of the central nervous system (i.e., neurosensitivity)(see Figure 2 for an illustration of the neurosensitivity hypothesis). In other words, sensitive people have more sensitive brains, which perceive information about the environment more readily and process such information in greater depth. This likely involves specific structural and functional aspects of various brain regions, including the amygdala and hippocampus.[1] These characteristics of the brain are then responsible for the typical experiences and behaviours associated with high sensitivity, such as experiencing emotions more strongly, responding more strongly to stressful situations or change, having a higher physiological reactivity, processing experiences in depth by thinking a lot about them, appreciating beauty, and picking up on subtle details.

Measurement of Environmental Sensitivity

In the last few decades, researchers have identified a wide range of individual characteristics that reflect or are associated with sensitivity to environmental influences. These include specific aspects of child temperament (e.g., difficult temperament, negative emotionality, and impulsivity), physiological reactivity (e.g., high cortisol reactivity) and various genetic variants that can be combined into a polygenic score of sensitivity. However, although these characteristics are important and capture some aspects of sensitivity they cannot be considered precise measures in themselves. Given that sensitivity is a complex trait, similar to other personality dimensions, it is more helpful to measure sensitivity with questionnaires, interviews, or behavioural observations that focus on the assessment of the typical behaviours and experiences that reflect the core attributes of sensitivity (i.e., perception and processing).

Questionnaires

A series of such sensitivity scales have been developed and are briefly described below.

The Highly Sensitive Person Scale(HSP)

The Highly Sensitive Person Scale (HSP)[9] is a 27-item self-report measure designed to assess Environmental Sensitivity in adults. Items are rated on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 = "Not at All" to 7 = "Extremely". Items search for a tendency to be easily overwhelmed by external and internal stimuli (e.g. "Do you find it unpleasant to have a lot going on at once?"), greater aesthetic awareness (e.g. "Do you seem to be aware of subtleties in your environment?"), and unpleasant sensory arousal to external stimuli (e.g. "Are you bothered by intense stimuli, like loud noises or chaotic scenes?"). The scale exists also in a brief version with 12 items.[17]

Highly Sensitive Child (HSC) scale

The Highly Sensitive Child (HSC) scale[18] is a 12-item self-report measure that is based on the adult HSP scale and has been designed to assess Environmental Sensitivity in children and adolescents between the ages of 8 and 18 years. Items included in the HSC scale are rated on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 = "Not at All" to 7 = "Extremely". Items are designed to capture different facets of sensitivity, such as the tendency to become mentally overwhelmed by both internal and external stimuli, greater appreciation of beauty, and overstimulation when experiencing intense sensory inputs. The HSC scale also exists in parent-rated version where parents can rate their child.

Observational measures

The Highly Sensitive Child – Rating System (HSC – RS)[19] is an observational measure designed to assess Environmental Sensitivity in three-year-old children. Children's responses in a series of standardised situations are observed and rated by trained experts.

Sensitivity groups

Orchids, tulips and dandelions

Initially, several psychological theories of sensitivity differentiated between two basic groups of people: those that are highly sensitive and those that are not.[9] The assumption was that about 20% of the general population are characterised by high sensitivity. Such individuals have been compared to the "Orchid", a plant that requires optimal conditions and care in order to flourish. In contrast, the remaining 80%, thought to be less sensitive, were compared to the "Dandelion", a plant that is robust and grows under many different conditions, to reflect this group's tendency to be less affected by the quality of the environment.[8][20] More recently, this two-group hypothesis has been challenged by several studies reporting that sensitivity is more likely a common trait that is best considered a spectrum from low to high. This means that all people are sensitive but to different degrees. These studies found that people fall into three, rather than two, distinct sensitivity groups along a spectrum of sensitivity from low (30% of the population), to medium (40%), to high (30%).[17][18][21] According to this research, the 40% that fall into the middle of the sensitivity continuum are referred to as "Tulips", a plant that is more delicate than the "Dandelion" but less fragile then the "Orchid".

See also

References

- Pluess, M., Individual Differences in Environmental Sensitivity. Child Development Perspectives, 2015. 9(3): p. 138-143.

- Terr, Abba I. (May 2003). "Environmental sensitivity". Immunology and Allergy Clinics of North America. National Center for Biotechnology Information. pp. 311–328. doi:10.1016/s0889-8561(02)00090-5. PMID 12803365. Retrieved 2020-08-10.

- US Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. "What is an environmental sensitivity index map?". oceanservice.noaa.gov. U.S.: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2020-08-10.

- Monroe, S.M. and A.D. Simons, Diathesis-stress theories in the context of life stress research: implications for the depressive disorders. Psychol Bull, 1991. 110(3): p. 406-25.

- Pluess, M. and J. Belsky, Vantage sensitivity: Individual differences in response to positive experiences. Psychological Bulletin, 2013. 139(4): p. 901-16.

- Belsky, J., Variation in susceptibility to rearing influences: An evolutionary argument. Psychological Inquiry, 1997. 8: p. 182-186.

- Belsky, J. and M. Pluess, Beyond diathesis stress: differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Psychol Bull, 2009. 135(6): p. 885-908.

- Boyce, W.T. and B.J. Ellis, Biological sensitivity to context: I. An evolutionary-developmental theory of the origins and functions of stress reactivity. Dev Psychopathol, 2005. 17(2): p. 271-301

- Aron, E.N. and A. Aron, Sensory-processing sensitivity and its relation to introversion and emotionality. J Pers Soc Psychol, 1997. 73(2): p. 345-68.

- Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J. and M.H. van IJzendoorn, Differential susceptibility to rearing environment depending on dopamine-related genes: new evidence and a meta-analysis. Development and Psychopathology, 2011. 23(1): p. 39-52.

- Schlomer, G.L., et al., Extending Previous cGxI Findings on 5-HTTLPR's Moderation of Intervention Effects on Adolescent Substance Misuse Initiation. Child Dev, 2017. 88(6): p. 2001-2012.

- Keers, R., et al., A Genome-Wide Test of the Differential Susceptibility Hypothesis Reveals a Genetic Predictor of Differential Response to Psychological Treatments for Child Anxiety Disorders. Psychotherapy and psychosomatics, 2016. 85(3): p. 146-158.

- Keers, R., et al., A genome-wide test of the differential susceptibility hypothesis reveals a genetic predictor of differential response to psychological treatments for child anxiety disorders. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 2016.

- Obradovic, J., X.A. Portilla, and P.J. Ballard, Biological Sensitivity to Family Income: Differential Effects on Early Executive Functioning. Child Dev, 2016. 87(2): p. 374-84.

- Xu, Y., et al., Interaction Effects of Life Events and Hair Cortisol on Perceived Stress, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptoms Among Chinese Adolescents: Testing the Differential Susceptibility and Diathesis-Stress Models. Front Psychol, 2019. 10(297): p. 297.

- Slagt, M., et al., Differences in Sensitivity to Parenting Depending on Child Temperament: A Meta-Analysis. Psychol Bull, 2016.

- Pluess, M., et al., People differ in their sensitivity to the environment: Association with personality traits and experimental evidence. In preparation.

- Pluess, M., et al., Environmental sensitivity in children: Development of the Highly Sensitive Child Scale and identification of sensitivity groups. Dev Psychol, 2018. 54(1): p. 51-70.

- Lionetti, F., et al., Observer-Rated Environmental Sensitivity Moderates Children's Response to Parenting Quality in Early Childhood. Developmental Psychology, 2019.

- Aron, E.N., A. Aron, and J. Jagiellowicz, Sensory processing sensitivity: a review in the light of the evolution of biological responsivity. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 2012. 16(3): p. 262-82.

- Lionetti, F., et al., Dandelions, tulips and orchids: evidence for the existence of low-sensitive, medium-sensitive and high-sensitive individuals. Translational Psychiatry, 2018. 8(1): p. 24.