Hawksbill sea turtle

The hawksbill sea turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) is a critically endangered sea turtle belonging to the family Cheloniidae. It is the only extant species in the genus Eretmochelys. The species has a global distribution that is largely limited to tropical and subtropical marine and estuary ecosystems.

| Hawksbill sea turtle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Hawksbill sea turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Suborder: | Cryptodira |

| Superfamily: | Chelonioidea |

| Family: | Cheloniidae |

| Subfamily: | Cheloniinae |

| Genus: | Eretmochelys Fitzinger, 1843 |

| Species: | E. imbricata |

| Binomial name | |

| Eretmochelys imbricata | |

| |

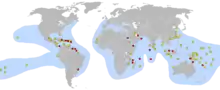

| Expert range map of the hawksbill sea turtle | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The appearance of the hawksbill is similar to that of other marine turtles. In general, it has a flattened body shape, a protective carapace, and flipper-like limbs, adapted for swimming in the open ocean. E. imbricata is easily distinguished from other sea turtles by its sharp, curving beak with prominent tomium, and the saw-like appearance of its shell margins. Hawksbill shells slightly change colors, depending on water temperature. While this turtle lives part of its life in the open ocean, it spends more time in shallow lagoons and coral reefs. The World Conservation Union, primarily as a result of human fishing practices, classifies E. imbricata as critically endangered.[1] Hawksbill shells were the primary source of tortoiseshell material used for decorative purposes. The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) regulates the international trade of hawksbill sea turtles and products derived from them.[3]

Taxonomy

Linnaeus described the hawksbill sea turtle as Testudo imbricata in 1766, in the 12th edition of his Systema Naturae.[4] In 1843, Austrian zoologist Leopold Fitzinger moved it into the genus Eretmochelys.[5] In 1857, the species was temporarily misdescribed as Eretmochelys imbricata squamata.[6]

Neither the IUCN[1] nor the United States Endangered Species Act assessment[7] processes recognize any formal subspecies, but instead recognize one globally distributed species with populations, subpopulations, or regional management units.

Fitzinger derived the genus name Eretmochelys from the Ancient Greek roots eretmo and chelys, corresponding to "oar" and "turtle", respectively, in reference to the turtles' oar-like front flippers. The species name imbricate is Latin, corresponding to the English term imbricate, in reference to the turtles' shingle-like, overlapping carapace scutes.

Description

Adult hawksbill sea turtles typically grow to 1 m (3 ft) in length, weighing around 80 kg (180 lb) on average. The heaviest hawksbill ever captured weighed 127 kg (280 lb).[8] The turtle's shell, or carapace, has an amber background patterned with an irregular combination of light and dark streaks, with predominantly black and mottled-brown colors radiating to the sides.[9]

Several characteristics of the hawksbill sea turtle distinguish it from other sea turtle species. Its elongated, tapered head ends in a beak-like mouth (from which its common name is derived), and its beak is more sharply pronounced and hooked than others. The hawksbill's forelimbs have two visible claws on each flipper.

An readily distinguished characteristic of the hawksbill is the pattern of thick scutes that make up its carapace. While its carapace has five central scutes and four pairs of lateral scutes like several members of its family, E. imbricata's posterior scutes overlap in such a way as to give the rear margin of its carapace a serrated look, similar to the edge of a saw or a steak knife. The turtle's carapace can reach almost 1 m (3 ft) in length.[10] The hawksbill appears to frequently employ its sturdy shell to insert its body into tight spaces in reefs.[11]

Crawling with an alternating gait, hawksbill tracks left in the sand are asymmetrical. In contrast, the green sea turtle and the leatherback turtle have a more symmetrical gait.[12][13]

Due to its consumption of venomous cnidarians, hawksbill sea turtle flesh can become toxic.[14]

The hawksbill is biofluorescent and is the first reptile recorded with this characteristic. It is unknown if the effect is due to the turtle's diet, which includes biofluorescent organisms like the hard coral Physogyra lichtensteini. Males have more intense pigmentation than females, and a behavioral role of these differences is speculated.[15][16]Hawksbill turtles are an endangered species under the protection of the US National Endangered Species Preservation act.

Carapace's serrated margin and overlapping scutes are evident in this individual

Carapace's serrated margin and overlapping scutes are evident in this individual Close-up of the hawksbill's distinctive beak

Close-up of the hawksbill's distinctive beak Fluorescent markings on Hawksbill sea turtle

Fluorescent markings on Hawksbill sea turtle- A Hawksbill turtle swims past a group of divers on the Great Barrier Reef, Australia

Distribution

Hawksbill sea turtles have a wide range, found predominantly in tropical reefs of the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic Oceans. Of all the sea turtle species, E. imbricata is the one most associated with warm tropical waters. Two significant subpopulations are known, in the Atlantic and Indo-Pacific.[17]

Atlantic subpopulation

In the Atlantic, hawksbill populations range as far west as the Gulf of Mexico and as far southeast as the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa.[17][18][19] They live off the Brazilian coast (specifically Bahia, Fernando de Noronha).

Along the East Coast of the United States, hawksbill sea turtle range from Virginia to Florida. In Florida, according to the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, hawksbills are found primarily on reefs in the Florida Keys and along the southeastern Atlantic coast. Several major nesting sites are found in coastal Palm Beach, Broward, and Dade County.[8] THE FLORIDA HAWKSBILL PROJECT, is a comprehensive research and conservation Program to study and protect the region’s hawksbill sea turtles and the habitats in which they live. Within the scope of this project, numerous studies have been undertaken to characterize the hawksbill aggregations found in southeast Florida waters, and educational programs have been developed to engage the local dive community in the protection of hawksbill sea turtles and coral reef habitats. This program is hosted by the National Save the Sea Turtle Foundation, located in Fort Lauderdale, Florida.Throughout their global range, hawksbill turtles are known to closely associate with coral reef habitats, mostly due to their preference for eating sponges and corals. Due to the large extent of Florida’s barrier reefs (approx. 350 linear miles), the Hawksbill Project focuses on representative sites in the northern, central, and southern sections of the Southeast Florida Reef Tract. The barrier reefs of northern Palm Beach County, the patch reefs of the northern Keys, and the finger reefs of Key West are the primary locations for their sampling efforts

In the Caribbean, the main nesting beaches are in the Lesser Antilles, Barbados,[20] Guadeloupe,[21] Tortuguero in Costa Rica,[22] and the Yucatan. They feed in the waters off Cuba[23] and around Mona Island near Puerto Rico,[24] among other places.

Indo-Pacific subpopulation

In the Indian Ocean, hawksbills are a common sight along the east coast of Africa, including the seas surrounding Madagascar and nearby island groups. Hawksbills are also common along the southern Asian coast, including the Persian Gulf, the Red Sea, and the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia coasts. They are present across the Malay Archipelago and northern Australia. Their Pacific range is limited to the ocean's tropical and subtropical regions. In the west, it extends from the southwestern tips of the Korean Peninsula and the Japanese Archipelago south to northern New Zealand.

The Philippines hosts several nesting sites, including the island of Boracay and Punta Dumalag in Davao City. Dahican Beach in Mati City, Davao Oriental, hosts one of the essential hatcheries of its kind, along with olive ridley sea turtles in the archipelagic country of the Philippines.[25] A small group of islands in the southwest of the archipelago is named the "Turtle Islands" because two species of sea turtles nest there: the hawksbill and the green sea turtle.[26] In January 2016, a juvenile was seen in Gulf of Thailand.[27] A 2018 article by The Straits Times reported that around 120 hawksbill juvenile turtles recently hatched at Pulau Satumu, Singapore.[28] Commonly found in Singapore waters, hawksbill turtles have returned to areas such East Coast Park and Palau Satumu to nest.[29] In Hawaii, hawksbills mostly nest on the "main" islands of Oahu, Maui, Molokai, and Hawaii.[30] In Australia, hawksbills are known to nest on Milman Island in the Great Barrier Reef.[31] Hawksbill sea turtles nest as far west as Cousine Island in the Seychelles, where the species since 1994 is legally protected, and the population is showing some recovery.[32] The Seychelles' inner islands and islets, such as Aldabra, are popular feeding grounds for immature hawksbills.[13][33]

Eastern Pacific subpopulation

In the eastern Pacific, hawksbills are known to occur from the Baja Peninsula in Mexico south along the coast to southern Peru.[17] Nonetheless, as recently as 2007, the species had been considered extirpated mainly in the region.[34] Important remnant nesting and foraging sites have since been discovered in Mexico, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Ecuador, providing new research and conservation opportunities. In contrast to their traditional roles in other parts of the world, where hawksbills primarily inhabit coral reefs and rocky substrate areas, in the eastern Pacific, hawksbills tend to forage and nest principally in mangrove estuaries, such as those present in the Bahia de Jiquilisco (El Salvador), Gulf of Fonseca (Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Honduras), Estero Padre Ramos (Nicaragua), and the Gulf of Guayaquil (Ecuador).[35] Multi-national initiatives, such as the Eastern Pacific Hawksbill Initiative, are currently pushing efforts to research and conserve the population, which remains poorly understood.

Habitat and feeding

Habitat

Adult hawksbill sea turtles are primarily found in tropical coral reefs. They are usually seen resting in caves and ledges in and around these reefs throughout the day. As a highly migratory species, they inhabit a wide range of habitats, from the open ocean to lagoons and even mangrove swamps in estuaries.[10][36] Little is known about the habitat preferences of early life-stage E. imbricata; like other young sea turtles, they are assumed to be completely pelagic, remaining at sea until they mature.[37]

Feeding

While they are omnivorous, sea sponges are their principal food; they constitute 70–95% of the turtles' diets.[38] However, like many spongivores, they feed only on select species, ignoring many others. Caribbean populations feed primarily on the orders Astrophorida, Spirophorida, and Hadromerida in the class Demospongiae.[39] Aside from sponges, hawksbills feed on algae, marine plants, cnidarians, comb jellies and other jellyfish, sea anemones, mollusks, fish and crustaceans.[10][40] They also feed on the dangerous jellyfish-like hydrozoan, the Portuguese man o' war (Physalia physalis). Hawksbills close their unprotected eyes when they feed on these cnidarians. The man o' war's stinging cells cannot penetrate the turtles' armored heads.[8]

Hawksbills are highly resilient and resistant to their prey. Some of the sponges they eat, such as Aaptos aaptos, Chondrilla nucula, Tethya actinia, Spheciospongia vesparium, and Suberites domuncula, are highly (often lethally) toxic to other organisms. In addition, hawksbills choose sponge species with significant numbers of siliceous spicules, such as Ancorina, Geodia (G. gibberosa[8]), Ecionemia, and Placospongia.[39]

Life history

Less is known about the life history of hawksbills by comparison to several other sea turtle species.[1][41] Their life history may be divided into three phases, the: (i) early life history phase from approximately 4–30 cm straight carapace length,[42] (ii) benthic phase when the immature turtles recruit to foraging areas, and (iii) reproductive phase, when individuals reach sexual maturity and begin periodically migrating to breeding grounds.[43][44] The early life history phase is not as geographically resolved as other sea turtle species. This phase appears to vary across ocean regions and may occur in both pelagic and nearshore waters, possibly lasting from 0–4 years of age.[42] One study from the central Pacific Ocean population used bomb radiocarbon (14C) dating and von Bertalanffy growth models to estimate hawksbills reach sexual maturity at ~ 72 cm and 29 years of age (range 23–36 years).[41] Hawksbills show a degree of fidelity after recruiting to the benthic phase[45] however, the movement to other similar habitats is possible.[46]

Breeding

Hawksbills mate biannually in secluded lagoons off their nesting beaches in remote islands throughout their range. The most significant nesting beaches are in Mexico, the Seychelles, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Australia. The mating season for Atlantic hawksbills usually spans April to November. Indian Ocean populations, such as the Seychelles hawksbill population, mate from September to February.[13] After mating, females drag their heavy bodies high onto the beach during the night. They clear an area of debris and dig a nesting hole using their rear flippers, then lay clutches of eggs and cover them with sand. Caribbean and Florida nests of E. imbricata typically contain around 140 eggs. After the hours-long process, the female returns to the sea.[10][18] Their nests can be found throughout beaches in about 60 countries.

Hatchlings, usually weighing less than 24 g (0.85 oz), hatch at night after around two months. These newly emergent hatchlings are dark-colored, with heart-shaped carapaces measuring approximately 2.5 cm (0.98 in) long. They instinctively crawl into the sea, attracted by the moon's reflection on the water (disrupted by light sources such as street lamps and lights). While they emerge under the cover of darkness, hatchlings that do not reach the water by daybreak are preyed upon by shorebirds, shore crabs, and other predators.[10]

Maturity

Hawksbills evidently reach maturity after 20 years.[18] Their lifespan is unknown.[47] Like other sea turtles, hawksbills are solitary for most of their lives; they meet only to mate. They are highly migratory.[48] Because of their tough carapaces, adults' only predators are humans, sharks, estuarine crocodiles, octopuses, and some pelagic fish[48] species.

A series of biotic and abiotic cues, such as individual genetics, foraging quantity and quality,[49] or population density, may trigger the maturation of the reproductive organs and the production of gametes and thus determine sexual maturity. Like many reptiles, all marine turtles of the same aggregation are highly unlikely to reach sexual maturity at the same size and thus age.[50]

Age at maturity has been estimated to occur between 10[51] and 25 years of age[52] for Caribbean hawksbills. Turtles nesting in the Indo-Pacific region may reach maturity at a minimum of 30 to 35 years.[53]

Evolutionary history

Within the sea turtles, E. imbricata has several unique anatomical and ecological traits. It is the only primarily spongivorous reptile. Because of this, its evolutionary position is somewhat unclear. Molecular analyses support Eretmochelys placement within the taxonomic tribe Carettini, including the carnivorous loggerhead and ridley sea turtles, rather than in the tribe Chelonini, which includes the herbivorous green turtle. The hawksbill probably evolved from carnivorous ancestors.[54]

Exploitation by humans

Throughout the world, hawksbill turtles have been hunted by humans, though it is illegal to capture, kill, and trade hawksbills in many countries today.[3][55] In some parts of the world, hawksbill turtles and their eggs continue to be exploited as food. As far back as the fifth century BCE, sea turtles, including the hawksbill, were eaten as delicacies in China.[56]

Beyond direct consumption for food, many cultures have also exploited hawksbill populations for their ornate carapace shells, known variously as tortoiseshell, turtle shell, and bekko.[57]

In China, where it was known as tai mei, the hawksbill is called the "tortoise-shell turtle", named primarily for its shell, which was used to make and decorate a variety of small items, as it was in the West.[56] Along the south coast of Java, stuffed hawksbill turtles are sold in souvenir shops, though numbers have decreased in the last two decades.[58] In Japan, the turtles are harvested for their shell scutes, called bekko in Japanese. Bekko is used in various personal implements, such as eyeglass frames and the shamisen (Japanese traditional three-stringed instrument) picks.[57] In 1994, Japan stopped importing hawksbill shells from other nations. Prior to this, the Japanese hawksbill shell trade was around 30,000 kg (66,000 lb) of raw shells per year.[23][59] In Europe, hawksbill sea turtle shells were harvested by the ancient Greeks and ancient Romans for jewellery, such as combs, brushes, and rings.[60] Recently, processed shells were regularly available in large amounts in countries including the Dominican Republic and Colombia.[61]

Global estimates of the historical exploitation of hawksbills have received recent attention. From 1950-1992, one pioneering study estimated that as many as 1.37 million adult hawksbills were killed in the international tortoiseshell trade alone.[1] With the aid of substantial additional trade data, including official trade records from the imperial Japanese archives, the international trade of tortoiseshell was recently updated to have killed approximately 8.98 million hawksbills (range 4.64 to 9.83 million) from 1844-1992.[62] Most of the trade occurred in the Pacific Ocean basin, and the countries of origin and trade routes bore similarity to what is known of illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing (IUU fishing).[62]

Conservation

Consensus has determined sea turtles, including E. imbricata to be at least threatened, because of their slow growth and maturity and low reproductive rates. Humans have killed many adult turtles, both accidentally and deliberately. Their existence is threatened due to pollution and loss of nesting areas because of coastal development. Biologists estimate that the hawksbill population has declined 80 percent in the past 100–135 years.[1] Human and animal encroachment threatens nesting sites, and small mammals dig up the eggs to eat.[10] In the US Virgin Islands, mongooses raid hawksbill nests (along with other sea turtles, such as Dermochelys coriacea) right after they are laid.[63]

In 1982, the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species first listed E. imbricata as endangered.[64] This endangered status continued through several reassessments in 1986,[65] 1988,[66] 1990,[67] and 1994[68] until it was upgraded in status to critically endangered in 1996.[1] Two petitions challenged its status as an endangered species prior to this, claiming the turtle (along with three other species) had several significant stable populations worldwide. These petitions were rejected based on their data analysis submitted by the Marine Turtle Specialist Group (MTSG). The MTSG data showed the worldwide hawksbill sea turtle population had declined by 80% in the three most recent generations, and no significant population increase had occurred as of 1996. CR A2 status was denied, however, because the IUCN did not find sufficient data to show the population likely to decrease by a further 80%.[69]

The species (along with the entire Cheloniidae family) has been listed in Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species.[3] This means commercial international trade (including in parts and derivatives) is prohibited and non-commercial international trade is regulated.[55]

The United States Fish and Wildlife Service and National Marine Fisheries Service have classified hawksbills as endangered under the Endangered Species Act[70] since 1970. The US government established several recovery plans[71] for protecting E. imbricata.[72]

The Zoological Society of London has inscribed the reptile as an EDGE species, meaning that it is both endangered and highly genetically distinct, and therefore of particular concern for conservation efforts.[73]

The World Wildlife Fund Australia (WWF-Australia) has several ongoing projects aiming at protecting the reptile.[74]

On Rosemary Island, an island in the Dampier Archipelago off the Pilbara coast of Western Australia, volunteers have been monitoring hawksbill turtles since 1986. In November 2020, a 60-year old turtle first tagged in November 1990 and again in 2011 returned to the same location.[75]

References

- Mortimer JA, Donnelly M (30 June 2008). "Eretmochelys imbricata". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, IUCN SSC Marine Turtle Specialist Group: e.T8005A12881238. doi:10.2305/iucn.uk.2008.rlts.t8005a12881238.en.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- CITES (14 June 2006). "Appendices". Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna. Archived from the original (SHTML) on 3 February 2007. Retrieved 5 February 2007.

- "Testudo imbricata Linnaeus, 1766". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 5 February 2007.

- "Eretmochelys Fitzinger, 1843". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 5 February 2007.

- "Eretmochelys imbricata squamata Agassiz, 1857". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 5 February 2007.

- "Hawksbill Sea Turtle (Eretmochelys Imbricata) 5-Year Review : Summary and Evaluation". US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2013.

- "Species Booklet: Hawksbill sea turtle". Virginia Fish and Wildlife Information Service. Virginia Department of Game & Inland Fisheries. Archived from the original on 24 September 2006. Retrieved 6 February 2007.

- "Hawksbill turtle – Eretmochelys imbricata: More information". Wildscreen. Archived from the original on 28 March 2007. Retrieved 5 February 2007.

- " Eretmochelys imbricata, Hawksbill Sea Turtle". MarineBio.org. Retrieved 5 February 2007.

- Witherington, B. (2006). Sea Turtles: An Extraordinary History of Some Uncommon Turtles. Minnesota: Voyager Press.

- "The Hawksbill Turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata)". turtles.org. Archived from the original on 21 February 2007. Retrieved 22 February 2007.

- "Hawksbill". SeychellesTurtles.org - Strategic Management of Turtles. Marine Conservation Society, Seychelles. Archived from the original on 17 October 2007. Retrieved 22 February 2007.

- "The Hawksbill Turtle: Eretmochelys imbricata". Auckland Zoo. Archived from the original on 9 October 2007. Retrieved 14 July 2007.

- Jane J. Lee. "Exclusive Video: First "Glowing" Sea Turtle Found". National Geographic.

- Gruber, David F.; Sparks, John S. (2015). "First Observation of Fluorescence in Marine Turtles". American Museum Novitates (3845): 1–8. doi:10.1206/3845.1. hdl:2246/6626. S2CID 86196418.

- "Species Fact Sheet: 'FIGIS - Fisheries Global Information System". United Nations. 2006. Retrieved 14 June 2009.

- "Hawksbill Sea Turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata)". North Florida Field Office. United States Fish and Wildlife Service. 9 December 2005. Retrieved 18 February 2007.

- Formia, Angela; Tiwari, Manjula; Fretey, Jacques; Billes, Alexis (2003). "Sea Turtle Conservation along the Atlantic Coast of Africa". Marine Turtle Newsletter. 100: 33–37. Retrieved 18 February 2007.

- Beggs, Jennifer A.; Horrocks, Julia A.; Krueger, Barry H. (2007). "Increase in hawksbill sea turtle Eretmochelys imbricata nesting in Barbados, West Indies" (PDF). Endangered Species Research. 3: 159–168. doi:10.3354/esr003159. Retrieved 6 December 2010.

- Kamel, Stephanie Jill; Delcroix, Eric (2009). "Nesting Ecology of the Hawksbill Turtle, Eretmochelys imbricata, in Guadeloupe, French West Indies from 2000–07". Journal of Herpetology. 43 (3): 367–76. doi:10.1670/07-231R2.1. S2CID 85699990.

- Bjorndal, Karen A.; Bolten, Alan B.; Lagueux, Cynthia J. (1993). "Decline of the Nesting Population of Hawksbill Turtles at Tortuguero, Costa Rica". Conservation Biology. 7 (4): 925–7. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1993.740925.x. JSTOR 2386826.

- Heppel, Selina S.; Larry B. Crowder (June 1996). "Analysis of a Fisheries Model for Harvest of Hawksbill Sea Turtles (Eretmochelys imbricata)". Conservation Biology. 10 (3): 874–880. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1996.10030874.x. JSTOR 2387111.

- Bowen, B. W.; Bass, A. L.; Garcia-Rodriguez, A.; Diez, C. E.; Van Dam, R.; Bolten, A.; Bjorndal, K. A.; Miyamoto, M. M.; Ferl, R. J. (1996). "Origin of Hawksbill Turtles in a Caribbean Feeding Area as Indicated by Genetic Markers". Ecological Applications. 6 (2): 566–72. doi:10.2307/2269392. JSTOR 2269392.

- Colacion, Artem; Danee Querijero (10 March 2005). "Uriel's journey home — a Young pawikan's story in Boracay". The Philippine Star. Archived from the original on 18 February 2006. Retrieved 6 February 2007.

- "Ocean Ambassadors - Philippine Turtle Islands". Coastal Resource & Fisheries Management of the Philippines. OneOcean.org. Retrieved 6 February 2007.

- "Wild Encounter Thailand". Facebook.

- "Almost 120 critically endangered turtles hatch at Raffles Lighthouse island". 26 September 2018.

- "Sea turtles on the Shores of Singapore".

- Hoover, John P. (2008). The Ultimate Guide to Hawaiian Reef Fishes, Sea Turtles, Dolphins, Whales, and Seals. Mutual Publishing. ISBN 978-1-56647-887-8.

- Loop, K. A.; Miller, J. D.; Limpus, C. J. (1995). "Nesting by the hawsbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) on Milman Island, Great Barrier Reef, Australia". Wildlife Research. 22 (2): 241–251. doi:10.1071/WR9950241.

- Allen, ZC; Shah, N. J.; Grant, A.; Derand, G-D.; Bell, D. (April 2010). "Hawksbill turtle monitoring in Cousin Island" (PDF). Endangered Species Research. 11 (3): 195–200. doi:10.3354/esr00281. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- Hitchins, P. M.; Bourquin, O.; Hitchins, S. (27 April 2004). "Nesting success of hawksbill turtles (Eretmochelys imbricata) on Cousine Island, Seychelles". Journal of Zoology. 264 (2): 383–389. doi:10.1017/S0952836904005904. Retrieved 21 February 2007.

- Gaos, Alexander; et al. (2010). "Signs of Hope in the Eastern Pacific: International collaboration reveals encouraging status of hawksbill turtles in the eastern Pacific". Oryx. 44 (4): 595. doi:10.1017/S0030605310000773.

- Gaos, Alexander; et al. (2011). "Shifting the life-history paradigm: discovery of novel habitat use by hawksbill turtles" (PDF). Biol Lett. 8 (1): 54–6. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2011.0603. PMC 3259967. PMID 21880620. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 December 2013.

- Lutz, P. L.; J. A. Musick (1997). The Biology of Sea Turtles. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-8422-6.

- Houghton, Jonathan D. R.; Martin J. Callow; Graeme C. Hays (2003). "Habitat utilization by juvenile hawksbill turtles (Eretmochelys imbricata, Linnaeus, 1766) around a shallow water coral reef" (PDF). Journal of Natural History. 37 (10): 1269–1280. doi:10.1080/00222930110104276. S2CID 55506652. Retrieved 17 March 2007.

- "Information About Sea Turtles: Hawksbill Sea Turtle – Sea Turtle Conservancy".

- Meylan, Anne (22 January 1988). "Spongivory in Hawksbill Turtles: A Diet of Glass". Science. 239 (4838): 393–395. Bibcode:1988Sci...239..393M. doi:10.1126/science.239.4838.393. JSTOR 1700236. PMID 17836872. S2CID 22971831.

- "Eretmochelys imbricata (Hawksbill)". Animal Diversity Web.

- Van Houtan, Kyle S.; Andrews, Allen H.; Jones, T. Todd; Murakawa, Shawn K. K.; Hagemann, Molly E. (13 January 2016). "Time in tortoiseshell: a bomb radiocarbon-validated chronology in sea turtle scutes". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 283 (1822): 20152220. doi:10.1098/rspb.2015.2220. PMC 4721088. PMID 26740617.

- Van Houtan, Kyle S.; Francke, Devon L.; Alessi, Sarah; Jones, T. Todd; Martin, Summer L.; Kurpita, Lauren; King, Cheryl S.; Baird, Robin W. (April 2016). "The developmental biogeography of hawksbill sea turtles in the North Pacific". Ecology and Evolution. 6 (8): 2378–2389. doi:10.1002/ece3.2034. PMC 4834323. PMID 27110350.

- Boulon, R. (1994). Growth Rates of Wild Juvenile Hawksbill Turtles, Eretmochelys imbricata, in St. Thomas, United States Virgin Islands. Copeia, 1994: 3 pp 811-814

- Van Dam, R. P.; Diez, C. E. (1997). "Diving behavior of immature hawksbill turtles (Eretmochelys imbricata) in a Caribbean reef habitat". Coral Reefs. 16 (2): 133–8. doi:10.1007/s003380050067. S2CID 2307103.

- Limpus, C. J. (1992). "The hawksbill turtle, Eretmochelys imbricata, in Queensland: population structure within a southern Great Barrier Reef feeding ground". Wildlife Research. 19 (4): 489–505. doi:10.1071/WR9920489.

- Boulon, R.H. 1989. Virgin Island turtle tags recovered outside the U. S. Virgin Islands. In: S.A. Eckert, K.L. Eckert & T.H. Richardson (Compilers). Proceedings of the Ninth Annual Workshop on Sea Turtle Conservation and Biology. U.S. Dept. of Commerce. NOAA Tech. Memo. NMFS-SEFC-232. pp 207.

- "Atlantic Hawksbill Sea Turtle Fact Sheet". New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- Edelman, Michael (2004). "Eretmochelys imbricata: Information". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Retrieved 4 February 2007.

- León, Y.M. and C.E. Diez (1999). "Population structure of hawksbill turtles on a foraging ground in the Dominican Republic". Chelonian Conservation and Biology. 3 (2): 230–236.

- Limpus CJ, Couper PJ, Read MA (1994). "The green turtle, Chelonia mydas, in Queensland: population structure in a warm temperate feeding area". Memoirs of the Queensland Museum. 35: 139–154.

- Moncada F, Carrillo E, Saenz A, Nodarse G (1999). "Reproduction and Nesting of the Hawksbill Turtle, Eretmochelys imbricata, in the Cuban Archipelago". Chelonian Conservation and Biology. 3 (2): 257–263.

- Diez CE, van Dam RP (2002). "Habitat effect on hawksbill turtle growth rates on feeding grounds at Mona and Monito Islands, Puerto Rico". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 234: 301–309. Bibcode:2002MEPS..234..301D. doi:10.3354/meps234301.

- Limpus, C.J. and Miller, J.D. |(2000) Final Report for Australian Hawksbill Turtle Population Dynamics Project. A Project Funded by the Japan Bekko Association to Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service. Dr. Colin J. Limpus and Dr. Jeffrey D. Miller, Planning and Research Division, Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service, P.O. Box 155, Brisbane Albert Street, Qld 4002, Australia.

- Bowen, Brian W.; Nelson, William S.; Avise, John C. (15 June 1993). "A Molecular Phylogeny for Marine Turtles: Trait Mapping, Rate Assessment, and Conservation Relevance". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 90 (12): 5574–5577. Bibcode:1993PNAS...90.5574B. doi:10.1073/pnas.90.12.5574. PMC 46763. PMID 8516304.

- UNEP-WCMC. "Eretmochelys imbricata". UNEP-WCMC Species Database: CITES-Listed Species. United Nations Environment Programme - World Conservation Monitoring Centre. A-301.003.003.001. Retrieved 5 February 2007.

- Schafer, Edward H. (1962). "Eating Turtles in Ancient China". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 82 (1): 73–74. doi:10.2307/595986. JSTOR 595986.

- "Sea Turtle Restoration Project : Hawksbill Sea Turtle". Archived from the original on 28 November 2010. Retrieved 25 October 2010. STRP Hawksbill Sea Turtle

- Nijman, Vincent (2015). "Decade's long open trade in protected marine turtles along Java's south coast". Marine Turtle Newsletter – via ResearchGate.

- Strieker, Gary (10 April 2001). "Tortoiseshell ban threatens Japanese tradition". CNN.com/sci-tech. Cable News Network LP, LLLP. Archived from the original on 11 March 2007. Retrieved 2 March 2007.

- Casson, Lionel (1982). "Periplus Maris Erythraei: Notes on the Text". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 102: 204–206. doi:10.2307/631139. JSTOR 631139. S2CID 161133205.

- "Turtles of the Caribbean: the curse of illegal trade". Newsroom. World Wide Fund for Nature. 1 October 2006. Archived from the original on 5 March 2007. Retrieved 27 February 2007.

- Miller, Emily A.; McClenachan, Loren; Uni, Yoshikazu; Phocas, George; Hagemann, Molly E.; Van Houtan, Kyle S. (March 2019). "The historical development of complex global trafficking networks for marine wildlife". Science Advances. 5 (3): eaav5948. Bibcode:2019SciA....5.5948M. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aav5948. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 6449156. PMID 30957017.

- Nellis, David W.; Vonnie Small (June 1983). "Mongoose Predation on Sea Turtle Eggs and Nests". Biotropica. 15 (2): 159–160. doi:10.2307/2387964. JSTOR 2387964.

- Groombridge, B. (1982). The IUCN Amphibia-Reptilia Red Data Book, Part 1: Testudines, Crocodylia, Rhynocehapalia. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. ISBN 9782880326012.

- IUCN Conservation Monitoring Centre (1986). 1986 IUCN Red List of Threatened Animals. Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK: IUCN. ISBN 978-2-88032-605-0.

- IUCN Conservation Monitoring Centre (1988). 1988 IUCN Red List of Threatened Animals. Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK: IUCN. ISBN 9782880329358.

- IUCN (1990). 1990 IUCN Red List of Threatened Animals. Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK.: IUCN.

- Groombridge, B. (1994). 1994 IUCN Red List of Threatened Animals. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. ISBN 978-2-8317-0194-3.

- Red List Standards & Petitions Subcommittee (18 October 2001). "Ruling of the IUCN Red List Standards and Petitions Subcommittee on Petitions against the 1996 Listings of Four Marine Turtle Species, 18 October 2001" (PDF). International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 December 2006. Retrieved 5 February 2007.

- "Endangered Species Act (ESA)". noaa.gov. 9 July 2019.

- "Recovery Plans for Endangered and Threatened Species". noaa.gov. 5 March 2021.

- "Species Profile: Hawksbill sea turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata)". USFWS Threatened and Endangered Species System (TESS). United States Fish and Wildlife Service. 2 June 1970. Archived from the original on 10 May 2007. Retrieved 5 February 2007.

- "Hawksbill Turtle".

- "Hawksbill turtle". WWF-Australia. 27 November 2020. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- Standen, Susan (22 November 2020). "Endangered hawksbill turtles return to nest on Pilbara coast raising hopes for conservation". ABC News. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

External links

- hawksbill-turtle/eretmochelys-imbricata Hawksbill sea turtle media from ARKive

- US National Marine Fisheries Service hawksbill sea turtle page

- Seaturtle.org Home to sea turtle conservation efforts such as the Marine Turtle Research Group and publisher of the Marine Turtle Newsletter.

- Hawksbill turtle in Bocas Del Toro

- Australian Government Department of the Environment

- Photos of Hawksbill sea turtle on Sealife Collection

- 3D animation of a Hawksbill sea turtle