European robin

The European robin (Erithacus rubecula), known simply as the robin or robin redbreast in Great Britain and Ireland, is a small insectivorous passerine bird that belongs to the chat subfamily of the Old World flycatcher family.[3] It is found across Europe, east to Western Siberia and south to North Africa; it is sedentary in most of its range except the far north.

| European robin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Gran Canaria robin call | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Muscicapidae |

| Genus: | Erithacus |

| Species: | E. rubecula |

| Binomial name | |

| Erithacus rubecula | |

| Subspecies | |

|

7–10, see text. | |

| |

| Range of E rubecula Breeding Resident Non-breeding Possible extinct & Introduced | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

It is about 12.5–14.0 cm (4.9–5.5 in) in length; the male and female are similar in colouration, with an orange breast and face lined with grey, brown upper-parts and a whitish belly.

Names

The distinctive orange breast of both sexes contributed to the European robin's original name of "redbreast", orange as a colour name being unknown in English until the 16th century, by which time the fruit had been introduced. The Dutch roodborstje, French rouge-gorge, Swedish rödhake, German Rotkehlchen, Italian pettirosso, Spanish petirrojo and Portuguese pisco-de-peito-ruivo all refer to the distinctively coloured front.[4]

In the 15th century, when it became popular to give human names to familiar species, the bird came to be known as robin redbreast, which was eventually shortened to robin.[5] As a given name, Robin is originally a smaller form of the name Robert. The term robin is also applied to some birds in other families with red or orange breasts. These include the American robin (Turdus migratorius), a thrush, and the Australasian robins of the family Petroicidae, the relationships of which are unclear.

Other older English names for the bird include ruddock and robinet. In American literature of the late 19th century, this robin was frequently called the English robin.[6]

Taxonomy and systematics

The European robin was described by Carl Linnaeus in 1758 in the 10th edition of his Systema Naturae under the binomial name Motacilla rubecula.[7] Its specific epithet rubecula is a diminutive derived from the Latin ruber, meaning 'red'.[8][9] The genus Erithacus was introduced by French naturalist Georges Cuvier in 1800, giving the bird its current binomial name E. rubecula.[10][11] The genus name Erithacus is from Ancient Greek[12] and refers to an unknown bird, now usually identified as robin.[13]

The genus Erithacus previously included the Japanese robin and the Ryukyu robin. These east Asian species were shown in molecular phylogenetic studies to be more similar to a group of other Asian species than to the European robin.[14][15] In a reorganisation of the genera, the Japanese and the Ryukyu robins were moved to the resurrected genus Larvivora leaving the European robin as the sole member of Erithacus.[3] The phylogenetic analysis placed Erithacus in the subfamily Erithacinae, which otherwise contained only African species, but its exact position with respect to the other genera was not resolved.[15]

The genus Erithacus was formerly classified as a member of the thrush family (Turdidae) but is now considered to belong to the Old World flycatcher family (Muscicapidae), specifically to the chats (subfamily Saxicolinae) which also include the common nightingale.[16]

Subspecies

In their large continental Eurasian range, robins vary somewhat, but do not form discrete populations that might be considered subspecies.[17][18] Robin subspecies are mainly distinguished by forming resident populations on islands and in mountainous areas. The robin found in the British Isles and much of western Europe, Erithacus rubecula melophilus, occurs as a vagrant in adjacent regions. E. r. witherbyi from northwest Africa, Corsica, and Sardinia closely resembles melophilus but has shorter wings.[19] The northeasternmost birds, large and fairly washed-out in colour, are E. r. tataricus. In the southeast of its range, E. r. valens of the Crimean Peninsula, E. r. caucasicus of the Caucasus and northern Transcaucasia, and E. r. hyrcanus southeastwards into Iran are generally accepted as significantly distinct.[19]

On Madeira and the Azores, the local population has been described as E. r. microrhynchos, and although not distinct in morphology, its isolation seems to suggest the subspecies is valid (but see below).[20]

Canary Islands robin

The most distinct birds are those of Gran Canaria (E. r. marionae) and Tenerife (E. r. superbus), which may be considered two distinct species or at least two different subspecies. They are readily distinguished by a white eye-ring, an intensely coloured breast, a grey line that separates the orange-red from the brown colouration, and the belly is entirely white.[21][22]

Cytochrome b sequence data and vocalisations[23] indicate that the Gran Canaria/Tenerife robins are indeed very distinct and probably derived from colonisation by mainland birds some 2 million years ago.[24]

Christian Dietzen, Hans-Hinrich Witt and Michael Wink published in 2003 in Avian Science a study called "The phylogeographic differentiation of the European robin Erithacus rubecula on the Canary Islands revealed by mitochondrial DNA sequence data and morphometrics: evidence for a new robin taxon on Gran Canaria?".[17] In it they concluded that Gran Canaria's robin diverged genetically from their European relatives as far back as 2.3 million years, while the Tenerife ones took another half a million years to make this leap, 1.8 million years ago. The most likely reason would be a different colonisation of the Canaries by this bird, which arrived at the oldest island first (Gran Canaria) and subsequently passed to the neighbouring island (Tenerife).[25]

A thorough comparison between marionae and superbus is pending to confirm that the first one is effectively a different subspecies. Initial results suggest that birds from Gran Canaria have wings about 10% shorter than those on Tenerife.[17] The west Canary Islands' populations are younger (Middle Pleistocene) and only beginning to diverge genetically. Robins from the western Canary Islands: El Hierro, La Palma and La Gomera (E. r. microrhynchus) are similar to the European type subspecies (E. r. rubecula).[19]

Finally, the robins which can be found in Fuerteventura are the European ones, which is not surprising as the species does not breed either in this island or in the nearby Lanzarote; they are wintering birds or just passing through during their long migration between Africa and Europe.[25]

Other robins

The larger American robin (Turdus migratorius) is a much larger bird named for its similar coloration to the European robin, but the two birds are not closely related, with the American robin instead belonging to the same genus as the common blackbird (T. merula), a species which occupies much of the same range as the European robin. The similarity between the European and American robins lies largely in the orange chest patch found in both species. This American species was incorrectly shown "feathering its nest" in London in the film Mary Poppins,[26] but it only occurs in the UK as a very rare vagrant.[27]

Some South and Central American Turdus thrushes are also called robins, such as the rufous-collared thrush. The Australian "robin redbreast", more correctly the scarlet robin (Petroica multicolor), is more closely related to crows and jays than it is to the European robin. It belongs to the family Petroicidae, whose members are commonly called "Australasian robins". The red-billed leiothrix (Leiothrix lutea) is sometimes named the "Pekin robin" by aviculturalists. Another group of Old World flycatchers, this time from Africa and Asia, is the genus Copsychus; its members are known as magpie-robins, one of which, the Oriental magpie robin (C. saularis), is the national bird of Bangladesh.[28]

Description

The adult European robin is 12.5–14.0 cm (4.9–5.5 in) long and weighs 16–22 g (0.56–0.78 oz), with a wingspan of 20–22 cm (8–8.5 in). The male and female bear similar plumage: an orange breast and face (more strongly coloured in the otherwise similar British subspecies E. r. melophilus), lined by a bluish grey on the sides of the neck and chest. The upperparts are brownish, or olive-tinged in British birds, and the belly whitish, while the legs and feet are brown. The bill and eyes are black. Juveniles are a spotted brown and white in colouration, with patches of orange gradually appearing.[29]

Distribution and habitat

The robin occurs in Eurasia east to Western Siberia, south to Algeria and on the Atlantic islands as far west as the Central Group of the Azores and Madeira. It is a vagrant in Iceland. In the southeast, it reaches Iran the Caucasus range.[1] Irish and British robins are largely resident but a small minority, usually female, migrate to southern Europe during winter, a few as far as Spain. Scandinavian and Russian robins migrate to Britain and western Europe to escape the harsher winters. These migrants can be recognised by the greyer tone of the upper parts of their bodies and duller orange breast. The continental European robins that migrate during winter prefer spruce woods in northern Europe, contrasting with its preference for parks and gardens in Great Britain.[30]

In southern Iberia, habitat segregation of resident and migrant robins occurs, with resident robins remaining in the same woodlands where they bred.[31]

Attempts to introduce the European robin into Australia and New Zealand in the latter part of the 19th century were unsuccessful. Birds were released around Melbourne, Auckland, Christchurch, Wellington and Dunedin by various local acclimatisation societies, with none becoming established. There was a similar outcome in North America, as birds failed to become established after being released in Long Island, New York in 1852, Oregon in 1889–1892, and the Saanich Peninsula in British Columbia in 1908–1910.[32]

Behaviour and ecology

_with_mealworm.jpeg.webp)

The robin is diurnal, although it has been reported to be active hunting insects on moonlit nights or near artificial light at night.[18] Well known to British and Irish gardeners, it is relatively unafraid of people and drawn to human activities involving the digging of soil, in order to look out for earthworms and other food freshly turned up. The robin is considered to be a gardener's friend, and from the traditional association of the red breast with the blood of Christ,[33] the robin would never be harmed. In continental Europe, on the other hand, robins were hunted and killed as were most other small birds, and are therefore more wary.[29] Robins also approach large wild animals, such as wild boar, which disturb the ground, to look for any food that might be brought to the surface.

In autumn and winter, robins will supplement their usual diet of terrestrial invertebrates, such as spiders, worms and insects, with berries and fruit.[30] They will also eat seed mixtures and suet placed on bird-tables.[29][34]

Male robins are noted for their highly aggressive territorial behaviour. They will fiercely attack other males and competitors that stray into their territories and have been observed attacking other small birds without apparent provocation. There are instances of robins attacking their own reflection.[35] Territorial disputes sometimes lead to fatalities, accounting for up to 10% of adult robin deaths in some areas.[36]

Because of high mortality in the first year of life, a robin has an average life expectancy of 1.1 years; however, once past its first year, life expectancy increases. One robin has been recorded as reaching 19 years of age.[37] A spell of very low temperatures in winter can, however, result in higher mortality rates.[38] The species is parasitised by the moorhen flea (Dasypsyllus gallinulae)[39] and the acanthocephalan Apororhynchus silesiacus.[40]

Breeding

Robins may choose a wide variety of sites for building a nest. In fact, anything which can offer some shelter, like a depression or hole, may be considered. As well as the usual crevices, or sheltered banks, other objects include pieces of machinery, barbecues, bicycle handlebars, bristles on upturned brooms, discarded kettles, watering cans, flower pots and hats. Robins will also nest in manmade nest boxes, favouring a design with an open front placed in a sheltered position up to 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) from the ground.[41] Nests are generally composed of moss, leaves and grass, with fine grass, hair and feathers for lining.[22]

Two or three clutches of five or six eggs are laid throughout the breeding season, which commences in March in Britain and Ireland. The eggs are a cream, buff or white speckled or blotched with reddish-brown colour, often more heavily so at the larger end.[42] When juvenile birds fly from the nests, their colouration is entirely mottled brown. After two to three months out of the nest, the juvenile bird grows some orange feathers under its chin, and over a similar period this patch gradually extends to complete the adult appearance of an entirely red-orange breast.[22]

Vocalisation

The robin produces a fluting, warbling ⓘ during the breeding season. Both the male and female sing during the winter, when they hold separate territories, the song then sounding more plaintive than the summer version.[29] The female robin moves a short distance from the summer nesting territory to a nearby area that is more suitable for winter feeding. The male robin keeps the same territory throughout the year. During the breeding season, male robins usually initiate their morning song an hour before civil sunrise, and usually terminate their daily singing around thirty minutes after sunset.[43] Nocturnal singing can also occur, especially in urban areas that are artificially lit during the night.[43] Some urban robins opt to sing at night to avoid daytime anthropogenic noise.[44]

Magnetoreception

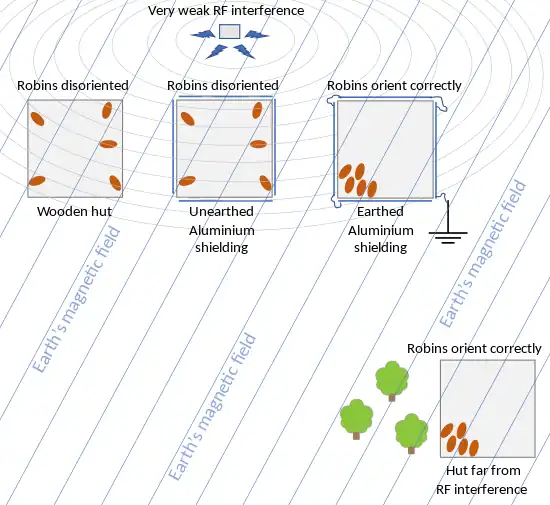

The avian magnetic compass of the robin has been extensively researched and uses vision-based magnetoreception, in which the robin's ability to sense the magnetic field of the earth for navigation is affected by the light entering the bird's eye. The physical mechanism of the robin's magnetic sense involves quantum entanglement of electron spins in cryptochrome in the bird's eyes.[46][45]

Conservation status

The European robin has an extensive range and a population numbering in the hundreds of millions. The species does not approach the vulnerable thresholds under the population trend criterion (>30 per cent decline over ten years or three generations); the population appears to be increasing. The International Union for Conservation of Nature evaluates it as least concern.[1]

Cultural depictions

The robin features prominently in British folklore and that of northwestern France, but much less so in other parts of Europe.[47] It was held to be a storm-cloud bird and sacred to Thor, the god of thunder, in Norse mythology.[48] Robins feature in the traditional children's tale Babes in the Wood; the birds cover the dead bodies of the children.[49]

The robin has become strongly associated with Christmas, taking a starring role on many Christmas cards since the mid-19th century.[49] The robin has appeared on many Christmas postage stamps. An old British folk tale seeks to explain the robin's distinctive breast. Legend has it that when Jesus was dying on the cross, the robin, then simply brown in colour, flew to his side and sang into his ear in order to comfort him in his pain. The blood from his wounds stained the robin's breast, and thereafter all robins carry the mark of Christ's blood upon them.[48][50]

An alternative legend has it that its breast was scorched fetching water for souls in Purgatory.[49] The association with Christmas more probably arises from the fact that postmen in Victorian Britain wore red jackets and were nicknamed "Robins"; the robin featured on the Christmas card is an emblem of the postman delivering the card.[51]

In the 1960s, in a vote publicised by The Times, the robin was adopted as the unofficial national bird of the United Kingdom.[52] In 2015, the robin was again voted Britain's national bird in a poll organised by birdwatcher David Lindo, taking 34% of the final vote.[53]

Several English and Welsh sports organisations are nicknamed "the Robins". The nickname is typically used for teams whose home colours predominantly use red. These include the professional football clubs Bristol City, Crewe Alexandra, Swindon Town, Cheltenham Town (with Bristol City, as of 2019,[54] Swindon Town, and Cheltenham Town also incorporating a robin image in their current badge designs), and, traditionally, Wrexham A.F.C., as well as the English rugby league team the Hull Kingston Rovers (whose home colours are white with a red band).[55] A small bird is an unusual choice, although it is thought to symbolise agility in darting around the field.[56]

Citations

- BirdLife International (2018). "Erithacus rubecula". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T22709675A131953953. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22709675A131953953.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- "Erithacus rubecula". Global Biodiversity Information Facility. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (2016). "Chats, Old World flycatchers". World Bird List Version 6.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- Holland, J. (1965). Bird Spotting. London, UK: Blandford. p. 225.

- Lack, D. (1950). Robin Redbreast. Oxford: Oxford, Clarendon Press. p. 44.

- Sylvester, Charles H. (2006). Journeys Through Bookland. BiblioBazaar, LLC. p. 155. ISBN 978-1-4264-2117-4.

- Linnaeus, Carolus (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata (in Latin). Vol. 1. Holmiae. (Laurentii Salvii). p. 188.

M. grisea, gula pectoreque fulvis.

- Simpson, D.P. (1979). Cassell's Latin Dictionary (5th ed.). London, UK: Cassell Ltd. p. 883. ISBN 978-0-304-52257-6.

- ruber. Charlton T. Lewis and Charles Short. A Latin Dictionary on Perseus Project.

- Mayr, Ernst; Paynter, Raymond A. Jr. (1964). Check-list of Birds of the World. Volume 10. Vol. 10. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Museum of Comparative Zoology. p. 32.

- Cuvier, George (1800). Leçons d'anatomie comparée. Volume 1 (in French). L'Institute National des Sciences et des Arts. Table 2. (The year is given on the title page as "VIII" in the French Republican Calendar)

- ἐρίθακος. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London, United Kingdom: Christopher Helm. p. 149. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- Seki, Shin-Ichi (2006). "The origin of the East Asian Erithacus robin, Erithacus komadori, inferred from cytochrome b sequence data". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 39 (3): 899–905. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2006.01.028. PMID 16529957.

- Sangster, G.; Alström, P.; Forsmark, E.; Olsson, U. (2010). "Multi-locus phylogenetic analysis of Old World chats and flycatchers reveals extensive paraphyly at family, subfamily and genus level (Aves: Muscicapidae)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 57 (1): 380–392. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2010.07.008. PMID 20656044.

- Monroe Jr. BL; Sibley CG (1993). A World Checklist of Birds. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. p. 228. ISBN 978-0-300-05549-8.

- Dietzen, Christian; Witt, Hans-Hinrich; Wink, Michael (2003). "The phylogeographic differentiation of the robin Erithacus rubecula on the Canary Islands revealed by mitochondrial DNA sequence data and morphometrics: evidence for a new robin taxon on Gran Canaria?" (PDF). Avian Science. 3 (2–3): 115–131.

- Pätzold, R. (1995). Das Rotkehlchen Erithacus rubecula. Neue Brehm-Bücherei (in German). Magdeburg/Heidelberg: Westarp Wissenschaften/Spektrum. ISBN 978-3-89432-423-0.

- Lack, D. (1946). "The Taxonomy of the Robin, Erithacus rubecula (Linnaeus)". Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club. 66: 55–64.

- Naish, Darren. "How Robins Became the Birds of Christmas". Scientific American Blog Network.

- Cramp S, ed. (1988). Handbook of the Birds of Europe, the Middle East and North Africa. The Birds of the Western Palearctic. Volume V. Tyrant Flycatchers to Thrushes. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-857508-5.

- "Robin (Erithacus rubecula)". Nhm.ac.uk.

- Bergmann, H.H.; Schottler, B. (2001). "Tenerife robin Erithacus (rubecula) superbus – a species of its own?". Dutch Birding. 23: 140–146.

- Although Dietzen et al. (2003) conclude that both the Tenerife and Gran Canaria populations are independently derived from mainland populations and should constitute two species or both be placed in E. rubecula as subspecies, their data does not allow for a definite conclusion. The alternative explanation – that Tenerife was colonised by already-distinct Gran Canaria robins – has not been explored and the proposed model relies only on probabilistic inference. Likewise, the seemingly exact molecular dating is doubtful as it assumes a molecular clock that may or may not be correct, and of course the assumption that the ancestor of all robins was similar in colouration to superbus and not the continental birds is, being inferred from their model of colonisation, entirely conjectural.

- César-Javier Palacios, "Hallazgo en Gran Canaria de una especie de petirrojo única en el mundo", Newspaper Canarias 7 (2006) Archived 7 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine; accessed February 24, 2015.

- "Mary Poppins (1964)". IMDb. Retrieved 21 January 2008.

- Roberts, John. "Village braced for invasion of twitchers as rare visitor flies in". Yorkshire Post. Archived from the original on 8 May 2006. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- "National icons of Bangladesh". Bangla 2000. Retrieved 5 August 2010.

- Hume, R. (2002). RSPB Birds of Britain and Europe. London: Dorling Kindersley. pp. 263. ISBN 978-0-7513-1234-8.

- Jonsson, Lars (1976). Birds of Wood, Park and Garden. Middlesex, England: Penguin. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-14-063002-2.

- De La Hera, I.; Fandos, G.; Fernández‐López, J.; Onrubia, A.; Pérez‐Rodríguez, A.; Pérez‐Tris, J.; Tellería, J. L. (2018). "Habitat segregation by breeding origin in the declining populations of European Robins wintering in southern Iberia". Ibis. 160 (2): 355–364. doi:10.1111/ibi.12549.

- Long, John L. (1981). Introduced Birds of the World: The worldwide history, distribution and influence of birds introduced to new environments. Terrey Hills, Sydney: Reed. p. 309. ISBN 978-0-589-50260-7.

- "Robin-Fact and Folklore". Birmingham and Black Country Wildlife Trust. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- Trust, Woodland. "What do Robins Eat? And What to Feed them". Woodland Trust. Retrieved 18 August 2021.

- RHS (December 2018). "December wildlife: Robins have a new family". The Garden RHS. 143 (12): 29.

- "The RSPB-Robin:Territory". RSPB website. Archived from the original on 11 December 2008. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- "Euring: European Longevity Records". euring.org. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- "The RSPB-Robin:Threats". RSPB website. Retrieved 17 May 2008.

- Rothschild, Miriam; Clay, Theresa (1957). Fleas, Flukes and Cuckoos. A study of bird parasites. New York: Macmillan. p. 113.

- Dimitrova, Z. M.; Murai, Éva; Georgiev, Boyko B. (1995). "The first record in Hungary of Apororhynchus silesiacus Okulewicz and Maruszewski, 1980 (Acanthocephala), with new data on its morphology". Parasitologia Hungarica. 28: 83–88. S2CID 82191853.

- "NEST BOXES : YOUR ESSENTIAL GUIDE" (PDF). Bto.org. pp. 12–13. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- Evans, G. (1972). The Observer's Book of Birds' Eggs. London, UK: Warne. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-7232-0060-4.

- Da Silva; Samplonius; Schlicht, Valcu; Gaston (2014). "Artificial night lighting rather than traffic noise affects the daily timing of dawn and dusk singing in common European songbirds". Behavioral Ecology. 25 (5): 1037–1047. doi:10.1093/beheco/aru103.

- Fuller RA, Warren PH, Gaston KJ (2007). "Daytime noise predicts nocturnal singing in urban robins". Biology Letters. 3 (4): 368–70. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0134. PMC 2390663. PMID 17456449.

- Hore, Peter J; Mouritsen, Henrik (April 2022). "The quantum nature of bird migration". Scientific American. 326 (4): 26–31. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0422-26. ISSN 0036-8733. Retrieved 29 January 2023. Web version published under title "How migrating birds use quantum effects to navigate".

- Hore, Peter J.; Mouritsen, Henrik (5 July 2016). "The Radical-Pair Mechanism of Magnetoreception". Annual Review of Biophysics. 45 (1): 299–344. doi:10.1146/annurev-biophys-032116-094545. PMID 27216936. S2CID 7099782.

- Ingersoll, p. 167

- Cooper, JC (1992). Symbolic and Mythological Animals. London, UK: Aquarian Press. p. 194. ISBN 978-1-85538-118-6.

- de Vries, Ad (1976). Dictionary of Symbols and Imagery. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Company. pp. 388–89. ISBN 978-0-7204-8021-4.

- Goodall, Simon. "European robin (Erithacus rubecula)". Greater Manchester Local Record Centre. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

In Christian folklore the robin got its red breast because it plucked a thorn from Jesus' crown-of-thorns during His crucifixion. A drop of Jesus' blood fell on to the bird and thereafter they had a red breast – for Christians the robin has long been associated with charity and piety.

- "Robin". BBC. Archived from the original on 29 December 2002. Retrieved 3 January 2008.

- "Robin". BBC News. Retrieved 24 September 2010.

- "Robin wins vote for UK's national bird". The Guardian. London. 10 June 2015. Retrieved 13 June 2016.

- "Robin sees City soar into new era". Bristol City. Retrieved 27 June 2019.

- "Hull Kingston Rovers: History". Official Website. Hull Kingston Rovers RLFC. Archived from the original on 27 January 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- Morris, Desmond (1981). The Soccer Tribe. London, UK: Jonathan Cape. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-224-01935-4.

General and cited references

- Ingersoll, Ernest (1923). "Fire-birds: The Robin and the Wren". Birds in Legend, Fable and Folklore. New York: Longmans, Green and Co. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

Further reading

- Lack, Andrew (2008). Redbreast: The Robin in Life and Literature. SMH Books. ISBN 978-0-9553827-2-7.

External links

- Erithacus rubecula in Field Guide: Birds of the World on Flickr

- European Robin videos, photos & sounds on Internet Bird Collection.

- Sonatura: Song of the European Robin (Archived 27 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine)

- Ageing and sexing (PDF; 2.9 MB) by Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze