Eritrea-Sudan border

The Eritrea–Sudan border (Tigrinya: ዶብ ኤርትራ-ሱዳን; Italian: Confine Eritrea-Sudan; Arabic: الحدود بين إريتريا والسودان) is 686 km (426 mi) in length and runs from Eritrea and Sudan's tripoint with Ethiopia in the south, to the town of Ras Kasar in the very south of Eritrea.[1][2] The border has been the site of several tensions, with deportations, border conflicts and colonialism by the United Kingdom and Italy. The border has also seen illegal acts such as human trafficking and hundreds of illegal crossings made by Eritreans.[3] Due to the Tigray War, Sudan saw a surge of Eritrean and Ethiopian civilians cross its border with Eritrea and by 2023 there were nearly 130,000 refugees and civilians confirmed living in the country.[4][5]

| Eritrea–Sudan border | |

|---|---|

Map of Eritrea, with Sudan to the west | |

| Characteristics | |

| Entities | |

| Length | 686 km (426 mi) |

| History | |

| Established | 24 May 1993 Eritrean War of Independence won in 1991, Eritrea officially declared a nation in 1993 after a referendum making Ethiopia landlocked. |

| Current shape | 24 May 1991 [lower-alpha 1] Eritrean–Ethiopian border conflict |

Description

The boundary starts in the north between the end of the Sudanese coast and the start of the Eritrean coast in the town of Ras Kasar, and proceeds overland in a very-deserted land in a southern direction, towards the town of Kerora where the city splits in half between both nations. The area then becomes primarily hilly, until becoming a mainly deserted terrain across the rest of the border. The largest town in the area is mainly Teseney, just a few miles away from the large city of Kassala. The border ends at a tripoint with a small city in Ethiopia called Himora.[6][7]

The border leaves the trifion between Eritrea, Ethiopia and Sudan, located on the course of the Tekezé River, near the Ethiopian town of Humera. It heads north for about 100 km before angling to the northeast. The land border ends at the shores of the Red Sea

The maritime border between the two countries then continues through the Red Sea for more than a hundred km, until it meets the maritime borders of Saudi Arabia. Administratively, the border separates the Eritrean regions of Anseba, Gash-Barka, and Semenawi-Keyih-Bahri from the Sudanese states of Kassala and Red Sea.

History

The border first emerged during the Scramble for Africa, a period of intense competition between European powers in the later 19th century for territory and influence in Africa.[8] The process culminated in the Berlin Conference of 1884, in which the European nations concerned agreed upon their respective territorial claims and the rules of engagements going forward. As a result of this France gained control the upper valley of the Niger River (roughly equivalent to the areas of modern Mali and Niger), and also the lands explored by Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza for France in Central Africa (roughly equivalent to modern Gabon and Congo-Brazzaville).[8] From these bases the French explored further into the interior, eventually linking the two areas following expeditions in April 1900 which met at Kousséri in the far north of modern Cameroon.[8] These newly conquered regions were initially ruled as military territories, with the two areas later organised into the federal colonies of French West Africa (Afrique occidentale française, abbreviated AOF) and French Equatorial Africa (Afrique équatoriale française, AEF).[9]

Italian occupation and war

The Italians colonised Eritrea in 1882 and ruled it until 1941.[10] In 1936, Italy invaded Ethiopia and declared it part of their colonial empire, which they called Italian East Africa. Italian Somaliland and Eritrea were also part of that entity, ruled by a Governor-General or Viceroy.[11]

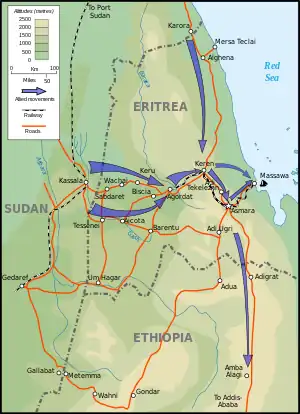

Allied invasion of Eritrea from Sudan (1941)

Redirects here: Allied invasion of Eritrea

Anglo-Egyptian Sudan or British Sudan shared a 1,000 mi (1,600 km) border with the AOI and on 4 July 1940, was invaded by an Fascist Italian force of about 6,500 men from Eritrea, which advanced on a railway junction at Kassala. The Italians forced the British garrison of 320 men of the SDF and some local police to retire after inflicting casualties of 43 killed and 114 wounded for ten casualties of their own. [12][13]

Conquered by the Allies in 1941, Italian East Africa was sub-divided. Ethiopia liberated its formerly Italian-occupied land in 1941. Italian Somaliland remained under Italian rule, but as a United Nations protectorate, not a colony, until 1960 when it united with British Somaliland, to form the independent state of Somalia.[14]

Eritrea was made a British protectorate from the end of World War II until 1951. However, there was debate as to what should happen with Eritrea after the British left. The British delegation to the United Nations proposed that Eritrea be divided along religious lines with the Christians to Ethiopia and the Muslims to Sudan.[14] In 1952, the United Nations decided to federate Eritrea to Ethiopia. About nine years later, Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie annexed Eritrea, triggering a thirty-year armed struggle in Eritrea.[15]

During the 1960s, the Eritrean independence struggle was led by the Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF). The independence struggle can properly be understood as the resistance to the annexation of Eritrea by Ethiopia long after the Italians left the territory. Additionally, one may consider the actions of the Ethiopian Monarchy against Muslims in the Eritrean government as a contributing factor to the revolution.[16]

Tensions and independence

A 30-year war of independence occurred in Eritrea between 1961 and 1991 and on 24 May 1991, the country declared de facto independence from Ethiopia. This caused a time of tense relations between both nations.[17] Between April to May 1993, the country launched a large referendum to declare de-jure independence and at the end ending with a 98.5% turnout within the population, this made Ethiopia landlocked and caused a long period of border conflicts for several decades.[18][19]

On 1 January 1956 Anglo-Egyptian Sudan declared independence as the Republic of Sudan; Eritrea followed decades later on 24 May 1993 and the border then became an international frontier between two independent states.[8][9]

By the end of 1993, shortly after Eritrea's independence from Ethiopia, Eritrea charged Sudan with supporting the activities of Eritrean Islamic Jihad, which carried out attacks against the Eritrean government.[20] Eritrea broke relations with Sudan at the end of 1994, became a strong supporter of the Sudan People's Liberation Movement/Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA), and permitted the opposition National Democratic Alliance to locate its headquarters in the former Sudan embassy in Asmara.[20] At the urging of the United States, Ethiopia and Eritrea joined Uganda in the so-called Front Line States strategy, which was designed to put military pressure on the Sudanese government.[20]

Eritrea's surprise 1998 invasion of the Ethiopian-administered border village of Badme dramatically changed the political situation in the region.[20] Operating on the axiom that the "enemy of my enemy is my friend," Sudan closed its border with Eritrea in 2002, and the Sudanese foreign minister charged in February 2003 that Eritrea had amassed forces along the border with Sudan. The Sudanese government also accused Eritrea of supporting rebel groups in Darfur.[20] The undemarcated border with Sudan also posed a problem for Eritrean external relations.[21]

During the spring of 2000, when tensions remained high in the area Sudan reported over 100,000 Eritreans had crossed the border into the country, most in dire conditions.[22]

.svg.png.webp)

Sudan closed its border with Eritrea in January 2018, citing concerns over illegal crossings and human trafficking which were staggering at the time.[23] Sudan reopened the border once again in 2019 after the country managed to have a successful coup d'état earlier in the year, An agreement between Isaias Afwerki and Mohammed Hamdan Dagalo was made.[24]

On 7 May 2023, The Guardian confirmed that the Eritrean government had forcefully deported over 3,500 Eritreans and Sudanese-Eritreans from Kassala during the large civil conflict in the country. Eritrea was reported to have used to border to send these civilians to Asmara and Teseney where over 100 of them were forcefully put in prison. Some of those detained were reported to be activists who had fled the dictatorship of Isaias Afwerki.[25]

Security

2018–19 border clashes and border crossing crisis

On 6 January 2018, Sudan closed its border with Eritrea after a huge influx of refugees emerged in the country, followed by extreme protests and a state of emergency declared a week before the announcement.[26] On the same day the governor of Kassala, Adam Jamaa announced that the state hadn't received anything of a border closure.[27]

The following day, on 7 January 2018. Kassala fully announced that the border had been officially closed stating:

Kassala governor, Adam Gemaa Adam, issued a decree ordering the closure of all border crossings with the state of Eritrea, based on the presidential decree … that declared the state of emergency in the state of Kassala.[28]

On the same day, Egyptian-backed UAE forces were deployed to the Eritrean border along with Sudanese forces as well. Kassala also announced a full on "state of emergency" for the entire state.[28] On 31 January 2019, Omar al-Bashir announced the reopening of the border in Kassala after over a year of large clashes which had killed at least 30 people in the last few months.[29]

2021 Sudan-Eritrea and Ethiopia border tensions

On 5 May 2021, Isaias Afwerki arrived at the Khartoum International Airport to discuss the large border dispute and Tigray tensions between both countries. The U.S. had ordered Eritrea to withdraw troops from the Tigray region fully due to the growing threat across the region. Eritrea had accused Sudan of siding with Ethiopia in the conflict, after Sudan had occupied a part of the province.[30][31]

2020–22 Eritrean refugee influx

Between 2020 and 2022, Eritrea reported a massive refugee crisis due to its war in Tigray with Sudan and Ethiopia. With thousands of refugees living in Tigray Refugee Camps and spreading to the rest of Sudan and Ethiopia.[32] The refugee crisis crew so much to the point where the UNHCR was reporting thousands of refugees a day entering Eastern Sudan, with thousands of them being disabled people and children separated from their families. Most of the refugees were also reported to have moved into Kassala and Gadaref states. The UNHCR also confirmed 5 border crossings and hundreds of refugee camps near the border.[33][34]

On 29 March 2020, the UN confirmed over 114,000 Eritrean refugees had either crossed the border or had gotten displaced within the nation or Ethiopia.[35]

Notes

- Due to the large border conflicts with Ethiopia, borders were finally confirmed in 2000, even tho they can be dated back to 1991 due to the de-facto independence

References

- "Eritrea–Sudan Land Boundary". Sovereign Limits. Retrieved May 13, 2023.

- "Eritrea country profile". BBC News. May 10, 2011. Retrieved May 13, 2023.

- Simpson, Gerry (February 11, 2014). ""I Wanted to Lie Down and Die"". Human Rights Watch.

- Webb, Jake. "Eritrean refugees trapped in Sudan try to escape to Halifax | SaltWire". www.saltwire.com. Retrieved May 13, 2023.

- Kibreab, Gaim (2005), "Eritreans in Sudan", in Ember, Melvin; Ember, Carol R.; Skoggard, Ian (eds.), Encyclopedia of Diasporas: Immigrant and Refugee Cultures Around the World, Boston, MA: Springer US, pp. 785–795, doi:10.1007/978-0-387-29904-4_81, ISBN 978-0-387-29904-4, retrieved May 13, 2023

- Nashed, Mat. "Will Ethiopia and Eritrea be dragged into Sudan's complex war?". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved May 13, 2023.

- "How Do I Get To Eritrea?". Young Pioneer Tours. February 5, 2018. Retrieved May 13, 2023.

- International Boundary Study No. 16 – Central African Republic-Sudan Boundary (PDF), June 22, 1962, retrieved December 18, 2019

- Brownlie, Ian (1979). African Boundaries: A Legal and Diplomatic Encyclopedia. Institute for International Affairs, Hurst and Co.

- Mesghenna, Yemane (2011). "Italian colonialism in Eritrea 1882–1941". Scandinavian Economic History Review. 37 (3): 65–72. doi:10.1080/03585522.1989.10408156.

- Epstein, M. (2016). The Statesman's Year-Book: Statistical and Historical Annual of the States of the World for the Year 1937. Springer. p. 675. ISBN 9780230270671.

- Schreiber, Stegemann & Vogel 2015, pp. 262–263.

- Raugh 1993, p. 72.

- Daniel Kendie, The Five Dimensions of the Eritrean Conflict 1941–2004: Deciphering the Geo-Political Puzzle. United States of America: Signature Book Printing, Inc., 2005, pp.17–8.

- "Ethiopia and Eritrea", Global Policy Forum

- "HISTORY OF ERITREA". www.historyworld.net. Retrieved September 20, 2017.

- "Eritrea – Postindependence Conflicts, Human Rights Violations, and Peace with Neighbours | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved May 13, 2023.

- "Elections in Eritrea". africanelections.tripod.com. Retrieved May 13, 2023.

- Lorch, Donatella (April 24, 1993). "Eritreans Voting on Independence From Ethiopia". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 13, 2023.

- Shinn, David H. (2015). "Ethiopia and Eritrea" (PDF). In Berry, LaVerle (ed.). Sudan: a country study (5th ed.). Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. pp. 280–282. ISBN 978-0-8444-0750-0.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Though published in 2015, this work covers events in the whole of Sudan (including present-day South Sudan) until the 2011 secession of South Sudan.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Though published in 2015, this work covers events in the whole of Sudan (including present-day South Sudan) until the 2011 secession of South Sudan.{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - "Eritrea-Sudan relations plummet". London: BBC. January 15, 2004. Retrieved June 7, 2006.

- "Human rights in Sudan". Amnesty International. Retrieved May 7, 2023.

- "Sudan political forces support decision to close border with Eritrea". Middle East Monitor. January 8, 2018. Retrieved May 13, 2023.

- Admin. "Eritrea and Sudan to reopen border crossings". Madote. Retrieved May 13, 2023.

- Salih, Zeinab Mohammed (May 7, 2023). "Eritrea accused of forcibly repatriating civilians caught up in Sudan fighting". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved May 13, 2023.

- "Sudan closes border with Eritrea". Reuters. January 6, 2018. Retrieved May 13, 2023.

- "Sudan closes border with Eritrea". The Financial Express. Retrieved May 13, 2023.

- "Sudan closes border with Eritrea". Middle East Monitor. January 7, 2018. Retrieved May 13, 2023.

- "Sudan's Bashir Says Border With Eritrea Reopens After Being Shut For a Year". VOA. Retrieved May 13, 2023.

- AfricaNews (May 4, 2021). "Eritrean president visits Sudan amid border tensions". Africanews. Retrieved May 13, 2023.

- "Eritrea's Isaias meets Sudanese leaders amid Ethiopia tensions". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved May 13, 2023.

- Plaut, Martin (November 9, 2022). "The forgotten victims of the Tigray war – the fate of 100,000 Eritrean refugees". Eritrea Hub. Retrieved May 14, 2023.

- "Sudan: Eritrean Refugees Overview in Sudan (as of 30 November 2022) – Sudan | ReliefWeb". reliefweb.int. Retrieved May 14, 2023.

- Official, Embassy Content (July 19, 2021). "Official Statement on the situation of Eritrean Refugees in Ethiopia (July 14, 2021) – Embassy of Ethiopia". Retrieved May 14, 2023.

- "America Team for Displaced Eritreans » Refugee Stats". Retrieved May 14, 2023.

Sources

- Raugh, H. E. (1993). Wavell in the Middle East, 1939–1941: A Study in Generalship. London: Brassey's. ISBN 978-0-08-040983-2.

- Schreiber, G.; et al. (2015) [1995]. Falla, P. S. (ed.). The Mediterranean, South-East Europe and North Africa, 1939–1941: From Italy's Declaration of non-Belligerence to the Entry of the United States into the War. Germany and the Second World War. Vol. III. Translated by McMurry, D. S.; Osers, E.; Willmot, L. (2nd pbk. trans. Oxford University Press, Oxford ed.). Freiburg im Breisgau: Militärgeschichtliches Forschungsamt. ISBN 978-0-19-873832-9.

Further reading

- Bascom, Johnathan B. 1990. Border Pastoralism in Eastern Sudan US: Taylor & Francis, Ltd. An article about the refugee influx and the war of independence between the border