Ernst Königsgarten

Ernst Königsgarten, also known as Arnošt Königsgarten (14 July 1880 – 15 January 1942) was an Austrian businessman and fencer. He was the youngest member of the Austrian team in the Olympic 1906 Intercalated Games in Athens in four competitions, finishing sixth with the sabre. In 1907, he was one of the co-founders of the Wiener Fechtklub (Vienna Fencing Club), trained in the fencing academy of Luigi Della Santa and sat on the board of the Austrian Fencing Association and the Wiener AC. He fled Vienna after the Anschluss and returned to his hometown of Brno, but was deported by the Nazis and died in Theresienstadt.

Early life and family

Ernst Königsgarten came from a wealthy and extensive Jewish family in Brno, now in the Czech Republic, but then still part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He had seven siblings, four sisters and three brothers.[1] His eldest brother Friedrich "Fritz" Königsgarten took over the family metal-working business founded by their father Ignatz and also sat on the board of the Altbrünner Lederwerke.[2]

In 1903, Ernst's brother Fritz married Elise "Lisi" Brück. The couple had a son, Hugo, in 1904, who became a well-known librettist, author and theatre critic. In 1907 a second son Heinrich (later Henry) was born. Fritz however died in 1908 after a serious illness, when Henry was only seven months old. At some later date Henry learnt that Ernst Königsgarten was not just his uncle, but also his biological father, from a brief affair with his sister-in-law Lisi. Ernst Königsgarten remained a lifelong bachelor and officially had no offspring, but treated his nephew Henry "like a son" and showed special interest in him.[3]

Ernst, Lisi, and her sons moved from Brno to Vienna, some 140 kilometers away, in 1911, and lived at different but neighbouring addresses. However they frequently holidayed together.[4] But in 1915 Lisi Königsgarten married the Berlin stockbroker Max Bohne and moved with him and her two sons to the German capital.[5][6][7] In 1919, Königsgarten acquired a villa in Altaussee (Fischerndorf 59), a traditional summer resort of the Austrian upper classes, from a son of the artist Carl von Binzer.[8] There also lived some Jewish artists and authors like Jakob Wassermann. From then on he used the Villa Königsgarten as a summer house, where Henry continued to visit him every summer.[9]

His brother Hugo Königsgarten (later Hugo Garten) (1904–1975) had obtained his doctorate in philosophy at Heidelberg University in 1930 and worked as a freelance writer in Berlin until 1933 when he moved back to Vienna. There he had established a career as a writer and theatre critic.[10]

Königsgarten's son Heinrich (later Henry Garton) (1907–1988) went to London in 1930 after completing his doctorate in law at Leipzig University, and then to Paris for five years before finally settling in England. During the Second World War he served as a soldier in the British Army, ending up in the Intelligence Corps. In 1944 he married an Englishwoman. They had two children, a son and a daughter.[11]

Königsgarten's grandson Michael Garton (born 1947) learned little about the background of his family, as both his grandmother Lisi and his parents barely talked about the past. However, after the death of his mother in 2010, he found papers and family records of Lisi Bohne-Königsgarten in his mother's attic and began to investigate. In 2015 he published the book In Search of Ernst on the history of the Königsgartens and the story of his discovery.[12]

Fencing career

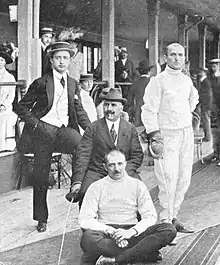

Despite suffering from a chronic eye disease, Königsgarten had a distinguished fencing career.[14] He fought left-handed with the foil and épée, but right-handed with his best weapon, the sabre. In 1906, at age 25, he was the youngest member of the Austrian team in the Olympic 1906 Intercalated Games in Athens in four competitions and finished sixth with the sabre. In 1907 he was one of the co-founders of the Wiener Fechtklub (Vienna Fencing Club), trained in the fencing academy of Luigi Della Santa and sat on the board of the Austrian Fencing Association and the Wiener AC.[15][16]

In the following years he competed in numerous tournaments throughout Europe, including Marienbad (1905), Prague, Milan and Trieste (1906), Carlsbad and Ostend (1907), and Baden-Baden (1909).[17] In some reports of those days he is referred to as Ernesto Königsgarten.[18] In 1908 the fencers from Vienna, including Königsgarten, performed demonstration fights in front of the English king Edward VII in Marienbad, who was staying there for talks with the French Foreign Minister, Georges Clemenceau, and the Russian diplomat Alexander Izvolsky. On this occasion the King presented a medal to Della Santa.[19]

Business career

Ignatz Königsgarten (1836–1927) noted in a family chronicle that his son Ernst had first trained as a merchant in Prague, then completed his one-year military service, where he achieved the rank of Lieutenant. Ernst Königsgarten then set out to become a leather goods manufacturer, and trained first in Liptószentmiklós in Hungary, before acquiring further theoretical knowledge in Freiberg, Saxony, and ultimately going to London to complete his training. However, in London he contracted a chronic eye disease. Despite excellent treatment in Moorfields Eye Hospital,[20] this illness made it impossible for him to continue his chosen career.[14]

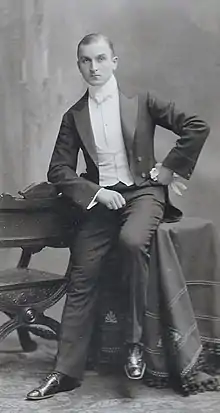

In society newspapers of the time Königsgarten was referred to as a man of independent means ("Privatier"),[21] but from 1923 he was mentioned as being a "banker".[22] He was described as an "elegant and distinguished young man",[23] He was also an officer in the Cavalry Reserve in France and a member of the Imperial Military Riding School in Vienna.[17] The writer Oskar Jellinek, brother-in-law of Königsgarten's brother Ludwig, attested to him as having "international blood that flowed through his veins" ("Weltblut, das seine Adern durchfloss".)[24]

Königsgarten put money into a variety of undertakings; he was a partner in Rudolf Klein Ges.mbH, which was devoted to the sale of car parts and accessories,[25] and a shareholder in Richard Hüpeden & Cie. which distributed bicycle, motorcycle and automotive parts.[26] In 1923 he joined the management of the Bovis Wurstwarenfabrik. Until August 1938 he also belonged to the Board of Directors of the Theater in der Josefstadt.[27] At the same time as these economic activities, he was still active as a fencer. During this period he lived first in an elegant apartment in No.10 Schwindgasse in Vienna's 4th district; his neighbours included, among others, the entrepreneur Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer and his wife Adele (Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I); the two families were also linked by marriage.[28][29] He subsequently moved to a first-floor apartment in No. 2 Argentinierstrasse in the same district, which enjoyed an enviable view onto the baroque Karlskirche opposite.[30]

Flight to Brno and death

On 12 March 1938 German troops rolled into Austria and the next day Austria was officially annexed into the German Reich. On the recommendation of Königsgarten, Henry had already moved to London in 1930. Hugo (who had returned to Vienna in 1933) fled Vienna on 13 March and joined Henry in London. Lisi had also moved back to Vienna in 1933 and in August 1938 managed to join her two sons in London, even taking some of her furniture with her. On 20 November 1938 Königsgarten too left Vienna, and perceiving Czechoslovakia to be safe, moved back to the family home in Dornichgasse 55 (now Dornych) in Brno, where his widowed brother Ludwig had taken over the family business after the death of his brother Fritz. According to shipping documents, Königsgarten even managed to take quite a few works of art with him.[31] In July 1941, Ludwig was forced to "sell" the family business to an Aryan competitor.[32]

Hugo Königsgarten, living in Vienna, was immediately in danger after the Anschluss, not only as a Jew, but also as a member of the "politically hottest cabaret of Vienna", the "ABC".[10] He left Austria on 13 March 1938 on the day of the Anschluss, on one of the last scheduled trains to Switzerland. Thanks to his Czech passport, he was able to cross the border unmolested. Two days later, the Gestapo arrived at his house to arrest him.[33] Thanks to his brother Henry living in England and being able to act as guarantor, he was able to get an entry visa and continue his involvement in cabaret, jointly forming the exile cabaret "Laterndl" in Hampstead. Like his mother and brother he was later able to obtain British citizenship. Lisi Bohne followed her sons to London in September 1938. Max Bohne (born 1883), who had also moved to Vienna in 1933, but by 1938 was living separately from Lisi, stayed behind in Vienna in 1938. After being forced into ever smaller accommodation, he too was deported to Theresienstadt on 20 August 1942, where he died a year later. Lisi only became aware of the fate of both Ernst Königsgarten and Max Bohne after the war. She died in London in 1956.[34]

On 5 December 1941 Königsgarten was deported from Brno to Theresienstadt on the second transport from that city, and he died there five weeks later, on 15 January 1942. On the same transport were his brother-in-law Leopold Schnürer, his sister Frieda, and their two daughters. They were all subsequently transported again, this time to Auschwitz, where they all perished. On Königsgarten's official death certificate, his profession is given as "sports teacher", and the cause of death as tubercular meningitis and cardiac paralysis.[35] His older brother Ludwig was himself deported to Theresienstadt in April 1942 as well, where he was put in charge of building the railway line into the camp, but once that project was completed he was transported again, this time to Auschwitz in December 1943 where he perished, possibly on the day he arrived.[36] In total, around 11,000 Jewish people were deported from Brno, of which only a few hundred survived.[37]

Aryanisation of property

The villa in Altaussee was seized and occupied by the Gestapo for the duration of the war. Königsgarten's "ethnographic collection" (consisting of local painted furniture and antiques) was confiscated and, as with other collections of Jewish property seized in the "wild Aryanisation of the Salzkammergut",[38] ended up in various museums, but also in the private property of the local representative of the Nazi Party Wilhelm Haenel.[39][40]

Thirty-four Jewish houses in the village came into the hands of prominent National Socialists such as Ernst Kaltenbrunner, who housed a lover there,[41] and Adolf Eichmann, who housed his wife there.[42] In 1945 Henry Königsgarten (now Garton) recovered the house and some of the belongings, but sold it in 1947. In the 1950s, it was rented by the writer Friedrich Torberg. Since 1979 the Villa Königsgarten has been owned by the artist Horst K. Jandl.[43][44]

On the outside of the cemetery wall in Altaussee is a small memorial plaque for Königsgarten. His son Henry had first installed one in the churchyard after the war, but this was mysteriously removed at least twice.[45] His grandson Michael Garton had a new one installed in May 2018.[46]

Notes and references

- Garton, In Search of Ernst p. xi.

- "Fritz Königsgarten – Encyklopedie dějin města Brna – Profil osobnosti". Encyklopedie.brna.cz (in Czech). Retrieved 2018-09-14.

- Garton, In Search of Ernst, p. 56/57.

- Brioni Insel-Zeitung, July 27, 1913, p. 7.

- Garton, In Search of Ernst, p. 58.

- "Ernst Königsgarten – Encyklopedie dějin města Brna – Profil osobnosti". Encyklopedie.brna.cz (in Czech). 1942-01-15. Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- The address in Berlin was: Brandenburgische Str. 46, Wilmersdorf.

- "Binzer, Carl von". Austria-forum.org. Retrieved 2018-08-11.

- Garton, In Search of Ernst, p. 90.

- "Zur Geschichte des Österreichischen Kabaretts". Kabarettarchiv.at. Retrieved 2018-08-11.

- Garton, In Search of Ernst, p. 33f.

- Garton, In Search of Ernst, p. 2.

- Békéssy was a participant of the 1912 Summer Olympic in Stockholm und competed for Hungary as a fencer. In the First World War he was killed in action and is worshiped as a hero in Hungary:

- Garton, In Search of Ernst p. 80/81.

- Michael Wenusch (1996), Geschichte des Wiener Fechtssport im 19. und 20 Jahrhundert, Dissertationen der Universitaet Wien (in German), vol. 3, Wien: WUV Universitätsverlag, pp. 92f., 151f, ISBN 3851141911 According to this source Luigi Della Santa was born in Modena in 1866 und passed his fencing diploma exams in 1887. Subsequently he worked as fencing master at the Military Academy of Modena, from 1885 to 1900 he was a teacher at the Bulgarian military academy in Sofia. Since 1900 he owned a fencing school in Brno. In 1905 he settled in Vienna; patrons made it possible for him to rent spacious rooms at Schwarzenbergplatz 7. During World War I he had to leave Austria.

- Alexander Juraske. "Der Wiener Athletiksport-Club und seine jüdischen Mitglieder". davidkultur.at. Retrieved 2018-08-17.

- "Ernst Königsgarten Bio, Stats, and Results". Sports-reference.com. Archived from the original on 2020-04-18. Retrieved 2016-08-20.

- Neues Wiener Abendblatt, April 8, 1908, p. 44.

- Das interessante Blatt, September 10, 1908, p. 19.

- Garton, In Search of Ernst p. 1.

- Curlisten Bad Ischl, August 9, 1904, p. 5.

- Wiener Zeitung, 14. September 1923, p. 11.

- Sport und Salon, May 8, 1909, p. 15.

- Richard Thieberger (1973), Fritz Martini/Walter Müller-Seidel/Bernhard Zeller, im Auftrag des Vorstands (ed.), "Oskar Jellinek (Brünn 1886–Los Angeles 1949). Mit einem bisher unveröffentlichten Emigrationsbericht", Jahrbuch der Deutschen Schillergesellschaft (in German), Stuttgart: Alfred Kröner, no. 17. Jahrgang, p. 96

- Matthias Marschik (2016), ""Der Herr Kommerzialrat". Theodor Schmidt und Rudolf Klein. Sporträume als Orte jüdischer Selbstvergewisserung in der Ersten Republik", Wiener Geschichtsblätter (in German), vol. 71, no. 4, p. 310

- (Wiener) Sporttagblatt, January 12, 1924, p. 12.

- Angela Eder (1998), Hilde Haider-Pregler (ed.), "Künstler und Kaufleute am Theater in der Josefstadt", Zeit der Befreiung. Wiener Theater Nach 1945 (in German), Wien: Picus, p. 150, ISBN 3-85452-413-7

- Illustrierte Kronen-Zeitung, March, 27, 1923, S. 7.

- Ferdinand's nephew and personal assistant Robert Bloch-Bauer (later Bentley) was married to Thea (née Stern), who was a third cousin of Ernst Königsgarten. Robert Bloch-Bauer's sister was Maria Altmann, who is noted for her successful legal campaign to reclaim from the Government of Austria five family-owned paintings by the artist Gustav Klimt which were stolen by the Nazis during World War II.

- "Adolph Lehmann's allgemeiner Wohnungs-Anzeiger [684]". Digital.wienbibliothek.at. 1934. Retrieved 2018-08-13.

- Garton, In Search of Ernst, p. 93.

- Garton, In Search of Ernst, p. 94.

- Garton, In Search of Ernst, p. 68f.

- Garton, In Search of Ernst, p. 54.

- "Königsgarten Arnošt: Todesfallanzeige, Ghetto Theresienstadt". Holocaust.cz (in Czech). Retrieved 2017-11-19.

- Garton, In Search of Ernst, p. 100.

- "Brünn (Mähren)". Aus der Geschichte der jüdischen Gemeinden im deutschen Sprachraum. Retrieved 2018-08-11.

- "Die Causa Löhne. Vermögensentzug ("Arisierungen") an jüdischen Liegenschaften in Bad Ischl" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-08-11. Retrieved 2018-08-14.

- "Arisierung von Kunst – Forum OÖ Geschichte". Ooegeschichte.at. Retrieved 2018-08-11.

- Birgit Schwarz: Hitlers Sonderauftrag Ostmark. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2018, ISBN 978-3-205-20355-1, S. 132 (, p. 132, at Google Books).

- Garton, In Search of Ernst, p. 106f.

- ""Eichmann ist meine Leidenschaft"". diepresse.com. 2010-09-03. Retrieved 2018-08-13.

- "Binzer, Carl von". Austria-Forum. Retrieved 2017-11-19.

- "Altaussee: Der Mythos der Lederhosenmetropole". Kurier.at. 2017-06-10. Retrieved 2018-08-11.

- Garton, In Search of Ernst p. 14f.

- Alpenpost, 21. Juli 2018, p. 10.

Bibliography

- Michael Garton (2015), In Search of Ernst. Discovering the Unspoken Fate of the Königsgartens, Oxford: Horsgate, ISBN 978-0-9927152-4-3

External links

- "Arnošt Königsgarten". Holocaust.cz. Retrieved 2018-08-11.