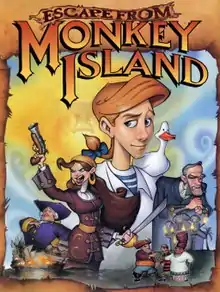

Escape from Monkey Island

Escape from Monkey Island is an adventure game developed and released by LucasArts in 2000. It is the fourth game in the Monkey Island series, and the sequel to the 1997 videogame The Curse of Monkey Island. It is the first game in the series to use 3D graphics and the second game to use the GrimE engine, which was upgraded from its first use in Grim Fandango.

| Escape from Monkey Island | |

|---|---|

| |

| Developer(s) | LucasArts |

| Publisher(s) | LucasArts |

| Designer(s) | Sean Clark Michael Stemmle |

| Programmer(s) | Michelle Hinners |

| Artist(s) | Chris Miles |

| Writer(s) | Sean Clark Michael Stemmle |

| Composer(s) | Clint Bajakian Michael Land Peter McConnell Anna Karney Michael Lande |

| Series | Monkey Island |

| Engine | GrimE iMUSE |

| Platform(s) | Microsoft Windows, Mac OS, PlayStation 2 |

| Release | Microsoft Windows Mac OS PlayStation 2 |

| Genre(s) | Graphic adventure |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

The game centers on the pirate Guybrush Threepwood, who returns home with his wife Elaine Marley after their honeymoon, to find her erroneously declared dead, and her office of governor up for election. Guybrush must find a way to restore Elaine to office, while uncovering a plot to turn the Caribbean into a tourist trap, headed by his nemesis LeChuck and an Australian conspirator Ozzie Mandrill.

Escape from Monkey Island won positive reviews and was a moderate commercial success. It was ultimately the last LucasArts adventure game to be released, as the company's later projects Full Throttle: Hell on Wheels and Sam & Max: Freelance Police were canceled in 2003 and 2004, respectively. The game was followed by Tales of Monkey Island, released by Telltale Games in 2009.

Gameplay

Escape from Monkey Island is an adventure game that consists of dialogue with characters and solving puzzles. The game is controlled entirely with the keyboard or alternatively with a joystick, making it the only non-point-and-click game in the Monkey Island series.

A feature of the game are action-lines: Guybrush will glance at any items that can be interacted with; the player can use 'Page Up' or 'Page Down' to select the item that he wants Guybrush to look at.

One of the hallmark aspects of the Monkey Island games, the insult swordfighting — the sword duels which were won by knowing the appropriate insults and responses — is briefly touched upon in the game as "insult armwrestling", and in an unwinnable insult duel against Ozzie Mandrill. In the second part of the game, the insult games are replaced by "Monkey Kombat", the name being a parody of Mortal Kombat with a symbol to match. Monkey Kombat is a sub-game akin to rock-paper-scissors, where the player needs to memorize lines of "monkey insults and retorts" which consist of per-game randomized compositions of "monkey words" like "oop", "chee", "ack" and "eek".

Plot

Guybrush Threepwood and Elaine Marley return to Mêlée Island from their honeymoon. They find that Elaine has been declared officially dead, her position as governor has been revoked and her mansion is scheduled to be demolished. The governorship is up for election, and suddenly a person known as Charles L. Charles presents himself as the lead candidate. As Elaine begins her campaign to recover her position, Guybrush hires navigator Ignatius Cheese in a game of insult arm-wrestling, meets again with two of his old "friends", Carla and Otis, and heads out to Lucre Island to recover the Marley family heirlooms and obtain the legal documents to save her mansion. During his trip, Guybrush learns of the Marley family's greatest secret: a voodoo talisman known as the Ultimate Insult, which allows the user to spread insults so heinous, it destroys the spirit and will of those who hear it. He is framed for bank robbery by crook Pegnose Pete at the hiring of the Australian land developer Ozzie Mandrill, but proves his innocence.

After acquiring the legal deeds and returning to the manor, Guybrush and Elaine discover that Charles L. Charles is really the shape-shifting Demon Pirate LeChuck, having been freed from his ice prison and seeking the Ultimate Insult. As Elaine continues her campaign, Guybrush searches the Jambalaya and Knuttin Atoll islands and recovers the pieces of the Ultimate Insult. Upon returning home, he is ambushed by the newly elected governor LeChuck and Ozzie Mandrill, who steal the pieces from him. The two villains are revealed to be working together, with Ozzie to rid of all pirates and turn the Caribbean into a resort and LeChuck out of debt to Ozzie for freeing him from his icy tomb and to use the Ultimate Insult to break Elaine and marry her. Feeling they might need Guybrush as a hostage, the two dump him on Monkey Island.

Despite temporary discouragement, Guybrush sets about making his escape. He learns the art of Monkey Kombat from the "monkey prince of Monkey Island" and, upon restoring the hermit Herman Toothrot's memory, discovers that the old man is actually Elaine's missing grandfather, having contracted amnesia twenty years prior due to being pushed into a whirlpool off the coast of Australia by Ozzie. After constructing an even bigger Ultimate Insult, Guybrush discovers that the colossal monkey head statue of the island hides a giant pilot-able monkey robot. He reactivates the Mecha and powers it and Herman and the island's monkeys join him in piloting it. With the robot, Guybrush manages to disable an Ultimate Insult amplifier made by Ozzie before returning to Mêlée. During this time, Ozzie has managed to capture Elaine and assemble the Ultimate Insult. When it appears to fail due to the lack of the amplifier, LeChuck takes matters into his own hands and possesses a statue of himself he had built shortly after his gubernatorial victory. Ozzie uses the Ultimate Insult to take control of LeChuck's statue form and engages Guybrush's monkey robot in Monkey Kombat. During the duel, Guybrush performs repeated ties, allowing Elaine to escape and causing LeChuck to smack his head in exasperation, crushing Ozzie and destroying the Ultimate Insult. LeChuck explodes. Guybrush and Elaine are reunited and Grandpa Marley resumes being the governor of Mêlée Island, so that the couple can go back to being pirates.

Development

The game was made with Sean Clark and Michael Stemmle as lead designers, both of whom worked on LucasArts' previous adventure titles Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis and Sam & Max Hit the Road. Sean Clark also worked on Loom and The Dig. Escape uses a slightly improved version of the GrimE engine introduced by Grim Fandango. Compared to the rest of the series, the SCUMM scripting language was replaced by the Lua programming language. This is referenced in-game; the pirate-themed SCUMM Bar, which first appeared in The Secret of Monkey Island, is replaced during the game with the tropical-themed Lua Bar.

A new version of the iMUSE interactive music system incorporating MP3 compression, among other changes, was built and used for the game. Interactive programming of the music and ambiance streams in the iMUSE system was done by lead sound designer Larry the O. Escape's introductory music is identical to that of the third game, unlike the earlier sequels which featured newly composed remixes of the well-known Monkey Island theme. Clint Bajakian, who had previously been an additional composer on Monkey Island 2: LeChuck's Revenge, acted as the game's main composer, with additional tracks by Michael Land (who had been the lead composer on the previous three Monkey Island games), Peter McConnell, Anna Karney, and Michael Lande (not to be confused with Michael Land).[6]

The voice cast saw the return of Dominic Armato as Guybrush, Earl Boen as LeChuck, Leilani Jones Wilmore as the Voodoo Lady and Denny Delk as Murray. The only major voice not to return was Alexandra Boyd who voiced Elaine in the previous game. She was replaced by Charity James. Stan is also voiced by a different actor, Pat Fraley. Additionally, characters who had previously appeared in The Secret of Monkey Island such as Carla, Otis and Herman Toothrot, are heard with voice actors for the first time.

The game was also released on PlayStation 2 in 2001. Apart from obvious control differences, the PS2 version only varies by a slightly higher polygon count and use of less pre-rendered material. Escape is the third LucasArts adventure game to have a console release, following The Secret of Monkey Island for the Sega CD and Maniac Mansion for the NES.

According to Heinrich Lenhardt of PC Gamer US, "[I]f it wasn't for the sales figures in Germany, LucasArts probably wouldn't have bothered doing another Monkey Island" after The Curse of Monkey Island.[7] In response to questions about the success of Grim Fandango and the viability of adventure games in the United States market, Tom Sarris of LucasArts defended the company's decision to make Escape from Monkey Island in 2000. He told GameSpot: "We look at the sales figures from a worldwide standpoint and ask ourselves if it still makes sense to make adventure games. Grim Fandango made a profit, so the answer is yes, it's still viable from a financial point of view".[8]

Reception

Sales

Discussing Escape from Monkey Island's performance in December 2000, Simon Jeffery of LucasArts said that the company was "really happy with the [game's] success". He noted that it was "selling well" in the United States and "incredibly well in Europe", which he called proof that a market still existed for adventure games, despite a widespread belief that the genre had died.[9] The game's computer version sold 55,275 copies and earned $2 million in the United States by the end of 2000, according to the market research firm PC Data.[10] In the German market, Escape debuted at #4 on Media Control's computer game sales chart for November 2000.[11] It placed ninth and 16th in its following two months, respectively.[12] PC Data estimated its sales in the United States at 32,576 units for 2001,[13] and 9,168 for the first six months of 2002.[14] Its jewel case SKU sold 11,061 copies in North America during 2003.[15]

In March 2003, LucasArts' Bill Tiller said that he was not sure what EMI sold, but thought it had decent numbers on the PC. In contrast, he reported that he "heard rumor of ... abysmal" sales for its PlayStation 2 release.[16] In retrospect, Rob Smith wrote in Rogue Leaders: The Story of LucasArts that "the stateside reception [for Escape of Monkey Island] was disappointing, but retail response was buoyed by overseas interest and sales—particularly in Europe, where the demand for adventure games hadn't fallen as flat".[17]

Critical response

| Aggregator | Score | |

|---|---|---|

| PC | PS2 | |

| GameRankings | 84%[18] | 83%[19] |

| Metacritic | 86/100[20] | 84/100[21] |

| Publication | Score | |

|---|---|---|

| PC | PS2 | |

| AllGame | ||

| Edge | 5 of 10[24] | N/A |

| Electronic Gaming Monthly | N/A | 9 of 10[25] |

| Eurogamer | 9 of 10[26] | N/A |

| Game Informer | 8.25 of 10[27] | 8.5 of 10[28] |

| GamePro | ||

| GameRevolution | B+[31] | B+[32] |

| GameSpot | 8.1 of 10[33] | 8.1 of 10[34] |

| GameSpy | 85%[35] | 91%[36] |

| IGN | 8.7 of 10[37] | 8.7 of 10[38] |

| Next Generation | ||

| Official U.S. PlayStation Magazine | N/A | |

| PC Gamer (US) | 85%[42] | N/A |

| Maxim | N/A | 6 of 10[43] |

| Playboy | N/A | 85%[44] |

The game was met with a generally favorable reception. The gameplay received criticism for its interface and the difficulty of keyboard or joystick control as compared to mouse controls. The "Monkey Kombat" was also criticized, with the GameSpot review stating that it was the single biggest problem in Escape from Monkey Island.[45] Another reviewer speculated that the designers presumably figured that combining insult fighting, cute monkeys, and a Mortal Kombat spoof would work well, but it did not.[46]

PC Zone gave it 82% and called it an enjoyable and fun game despite not having innovations.[47] Adventure Gamers gave it four stars out of five and called it "a quality adventure game"; he was critical of restyling of the old locations on Mêlée Island and Monkey Island, but was satisfied with game's ending.[48] Jeff Lundrigan in Next Generation, rated it three stars out of five, having a praise on the story, characters, and production values.[39]

Playboy gave the PS2 version a score of 85% and said that the game captures aging Marx Brothers appeal, but with modern-day flair, also having high remarks of gameplay and characters.[44] Maxim, however, gave the same version six out of ten, criticising tongue-in-cheek jokes as tasteless.[43] Jeff Lundrigan reviewed the PlayStation 2 version of the game for Next Generation, rating it three stars out of five, and stated that the puzzles are confusing, but recommended to the gamers who have a patience to solve it.[40]

Awards

Escape from Monkey Island was a runner-up for GameSpot's, The Electric Playground's, IGN's and Computer Gaming World's awards for the best computer adventure title of 2000, all of which went to The Longest Journey.[49][50][51][52] Computer Gaming World's editors remarked that Escape from Monkey Island is "a lot of fun and is strongly recommended to fans, but it's a few jokes and puzzles short of being a classic like the other games in the series".[52] However, CNET Gamecenter named it the year's best adventure game over The Longest Journey, and its editors wrote that they could not "imagine a better graphic adventure" than LucasArts' title. It was also a finalist for their overall game of the year award, which went to The Sims.[53]

The editors of Computer Games Magazine similarly nominated Escape from Monkey Island for their 2000 "Adventure Game of the Year" award.[54] During the 4th Annual Interactive Achievement Awards, the Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences nominated Escape from Monkey Island in the categories for "PC Action/Adventure", "Art Direction", and "Original Musical Composition".[55]

- E3 2000 Game Critics Awards: Best Action/Adventure Game

References

- "ZDNet: GameSpot: PC Home: Escape from Monkey Island". ZDNet. 2000-11-21. Archived from the original on 2000-11-21. Retrieved 2023-05-24.

- "Escape from Monkey Island Release Information for PC". GameFAQs. Archived from the original on October 14, 2015. Retrieved October 11, 2015.

- "Aspyr: Inside Aspyr". 2003-08-09. Archived from the original on 2003-08-09. Retrieved 2023-03-27.

- "Date Set For Monkey Island". IGN. 2001-05-24. Retrieved 2023-05-24.

- "Escape from Monkey Island Release Information for PlayStation 2". GameFAQs. Archived from the original on October 15, 2015. Retrieved October 11, 2015.

- Larry the O personal files, by permission

- Lenhardt, Heinrich (July 2001). "Gaming Goes Global". PC Gamer US. 8 (7): 44–47, 50–52.

- Ajami, Amer (September 8, 2000). "Escape from Monkey Island Preview". GameSpot. Archived from the original on November 17, 2000.

- Rubenstein, Glenn (December 1, 2000). "Pt. IV: Future Star Wars Games". CNET Gamecenter. Archived from the original on January 24, 2001.

- "It's All in the Numbers". PC Gamer. Future US. 8 (4): 40, 41. April 2001.

- "Stand: November 2000" (in German). Verband der Unterhaltungssoftware Deutschland. Archived from the original on December 9, 2000. Retrieved August 11, 2019.

- "Zeitraum: Januar 2001" (in German). Verband der Unterhaltungssoftware Deutschland. Archived from the original on February 7, 2001. Retrieved August 11, 2019.

- Sluganski, Randy (March 2002). "State of Adventure Gaming - March 2002 - 2001 Sales Table". Just Adventure. Archived from the original on June 19, 2002. Retrieved May 19, 2018.

- Sluganski, Randy (August 2002). "State of Adventure Gaming - August 2002 - June 2002 Sales Table". Just Adventure. Archived from the original on March 14, 2005. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- Sluganski, Randy (March 2004). "Sales December 2003 - The State of Adventure Gaming". Just Adventure. Archived from the original on April 11, 2004. Retrieved May 19, 2018.

- "The Celebrity Corner; Interview with Bill Tiller". The Inventory. No. 5. Just Adventure. March 2003. pp. 8–19. Archived from the original on August 13, 2006. Retrieved July 14, 2018.

- Smith, Rob (November 26, 2008). Rogue Leaders: The Story of LucasArts. Chronicle Books. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-8118-6184-7.

- "Escape from Monkey Island for PC". GameRankings. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on 2014-04-24. Retrieved 2014-04-24.

- "Escape from Monkey Island for PlayStation 2". GameRankings. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on 2014-04-24. Retrieved 2014-04-24.

- "Escape from Monkey Island for PC Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on 2013-10-10. Retrieved 2014-04-24.

- "Escape from Monkey Island for PlayStation 2 Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on 2016-05-24. Retrieved 2014-04-24.

- Norands, Alec. "Escape From Monkey Island (PC) - Review". AllGame. Archived from the original on 2014-11-13. Retrieved 2015-09-21.

- Barnes, J.C. "Escape From Monkey Island (PS2) - Review". AllGame. Archived from the original on 2014-11-13. Retrieved 2015-09-21.

- "Escape from Monkey Island (PC)". Edge. No. 93. January 2001.

- "Escape from Monkey Island (PS2)". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 146. August 2001. p. 111.

- Bramwell, Tom (9 December 2000). "Escape From Monkey Island Review (PC)". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on 12 October 2013. Retrieved 2013-10-09.

- Reppen, Erik (January 2001). "Escape from Monkey Island (PC)". Game Informer. No. 93. p. 128.

- Reiner, Andrew (September 2001). "Escape from Monkey Island (PS2)". Game Informer. No. 101. Archived from the original on 2008-01-30. Retrieved 2014-04-24.

- Sean Molloy (2000-11-13). "Escape from Monkey Island Review for PC on GamePro.com". GamePro. Archived from the original on 2005-02-12. Retrieved 2014-04-24.

- Star Dingo (2001-06-18). "Escape from Monkey Island Review for PS2 on GamePro.com". GamePro. Archived from the original on 2005-02-12. Retrieved 2014-04-24.

- Gee, Brian (November 2000). "Escape From Monkey Island Review (PC)". Game Revolution. Archived from the original on 2014-04-24. Retrieved 2014-04-24.

- Silverman, Ben (June 2001). "Escape From Monkey Island - PS2". Game Revolution. Archived from the original on 2007-08-24. Retrieved 2014-04-24.

- Dulin, Ron (2000-11-09). "Escape from Monkey Island Review (PC)". GameSpot. Retrieved 2017-03-28.

- Kasavin, Greg (2001-06-21). "Escape from Monkey Island Review (PS2)". GameSpot. Retrieved 2014-04-24.

- Schembri, Tamara "Curacao" (2000-11-20). "Escape from Monkey Island (PC)". GameSpy. Archived from the original on 2008-07-02. Retrieved 2014-04-24.

- Garbutt, Russell (2001-06-25). "Escape from Monkey Island". PlanetPS2. Archived from the original on 2001-08-19. Retrieved 2014-04-24.

- Lopez, Vincent (2000-11-08). "Escape From Monkey Island (PC)". IGN. Archived from the original on 2014-02-19. Retrieved 2014-04-24.

- Smith, David (2001-06-20). "Escape From Monkey Island (PS2)". IGN. Archived from the original on 2014-04-24. Retrieved 2014-04-24.

- Lundrigan, Jeff (February 2001). "Escape from Monkey Island". Next Generation. Lifecycle 2, Vol. 3 (2): 85.

- Lundrigan, Jeff (July 2001). "Finals". Next Generation. Vol. 4, no. 7. Imagine Media. p. 83.

- "Escape From Monkey Island". Official U.S. PlayStation Magazine. August 2001.

- Kuo, Li C. (February 2001). "Escape From Monkey Island". PC Gamer: 85. Archived from the original on 2005-03-18. Retrieved 2014-04-24.

- Steinberg, Scott (2001-06-18). "Escape From Monkey Island (PS2)". Maxim. Archived from the original on 2014-04-25. Retrieved 2014-11-01.

- "Escape from Monkey Island (PS2)". Playboy. 2001. Archived from the original on 2001-07-14. Retrieved 2015-09-21.

- Dulin, Ron (2000-11-09). "Escape from Monkey Island Review (PC)". GameSpot. Archived from the original on 2014-04-14. Retrieved 2014-04-24.

- UHS: Escape from Monkey Island Review Archived 2006-08-07 at the Wayback Machine

- "PC Review: Escape From Monkey Island". PC Zone. 2001-08-13. Archived from the original on 2008-06-23. Retrieved 2014-04-24.

- Bronstring, Marek (2002-05-20). "Escape From Monkey Island review". Adventure Gamers. Archived from the original on 2014-04-24. Retrieved 2014-04-24.

- "Blister Awards 2000". The Electric Playground. February 2001. Archived from the original on February 8, 2002.

- "Best and Worst of 2000". GameSpot. Archived from the original on February 2, 2002.

- "IGNPC's Best of 2000 Awards". IGN. January 26, 2001. Archived from the original on April 13, 2001.

- "The 2001 Premier Awards; Games of the Year". Computer Gaming World. No. 201. April 2001. pp. 72–80, 82, 83.

- "Gamecenter's computer game awards for 2000". CNET Gamecenter. January 25, 2001. Archived from the original on February 8, 2001. Retrieved June 23, 2018.

- "Computer Games Magazine announces nominees for annual best in computer gaming awards". Computer Games Magazine. February 8, 2001. Archived from the original on February 9, 2005.

- "D.I.C.E. Awards By Video Game Details Escape from Monkey Island". interactive.org. Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences. Retrieved 9 August 2023.

External links

- Escape from Monkey Island at IMDb

- Official Escape from Monkey Island website at LucasArts (currently down)

- Escape from Monkey Island at MobyGames