Alcohol withdrawal syndrome

Alcohol withdrawal syndrome (AWS) is a set of symptoms that can occur following a reduction in alcohol use after a period of excessive use.[1] Symptoms typically include anxiety, shakiness, sweating, vomiting, fast heart rate, and a mild fever.[1] More severe symptoms may include seizures, and delirium tremens (DTs) which can be fatal in untreated patients.[1] Symptoms start at around 6 hours after last drink.[2] Peak incidence of seizures occurs at 24-36 hours[4] and peak incidence of delirium tremens is at 48-72 hours.[5]

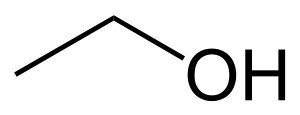

| Alcohol withdrawal syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ethanol | |

| Specialty | Toxicology, addiction medicine, intensive care medicine, psychiatry |

| Symptoms | Anxiety, shakiness, sweating, vomiting, fast heart rate, mild fever[1] |

| Usual onset | Six hours following the last drink[2] |

| Duration | Up to a week[2] |

| Causes | Reduction or cessation of alcohol intake after a period of excessive use[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol (CIWA-Ar)[3] |

| Treatment | Benzodiazepines, thiamine[2] |

| Frequency | ~50% of people with alcoholism upon reducing use[3] |

Alcohol withdrawal may occur in those who are alcohol dependent.[1] This may occur following a planned or unplanned decrease in alcohol intake.[1] The underlying mechanism involves a decreased responsiveness of GABA receptors in the brain.[3] The withdrawal process is typically followed using the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol scale (CIWA-Ar).[3]

The typical treatment of alcohol withdrawal is with benzodiazepines such as chlordiazepoxide or diazepam.[2] Often the amounts given are based on a person's symptoms.[2] Thiamine is recommended routinely.[2] Electrolyte problems and low blood sugar should also be treated.[2] Early treatment improves outcomes.[2]

In the Western world about 15% of people have problems with alcoholism at some point in time.[3] Alcohol depresses the central nervous system, slowing cerebral messaging and altering the way signals are sent and received. Progressively larger amounts of alcohol are needed to achieve the same physical and emotional results. The drinker eventually must consume alcohol just to avoid the physical cravings and withdrawal symptoms. About half of people with alcoholism will develop withdrawal symptoms upon reducing their use, with four percent developing severe symptoms.[3] Among those with severe symptoms up to 15% die.[2] Symptoms of alcohol withdrawal have been described at least as early as 400 BC by Hippocrates.[6][7] It is not believed to have become a widespread problem until the 1700s.[7]

Signs and symptoms

Signs and symptoms of alcohol withdrawal occur primarily in the central nervous system. The severity of withdrawal can vary from mild symptoms such as insomnia, trembling, and anxiety to severe and life-threatening symptoms such as alcoholic hallucinosis, delirium tremens, and autonomic instability.[8][9]

Withdrawal usually begins 6 to 24 hours after the last drink.[10] Symptoms are worst at 24 to 72 hours, and improve by seven days.[2][3] To be classified as alcohol withdrawal syndrome, patients must exhibit at least two of the following symptoms: increased hand tremor, insomnia, nausea or vomiting, transient hallucinations (auditory, visual or tactile), psychomotor agitation, anxiety, generalized tonic–clonic seizures, and autonomic instability.[11]

The severity of symptoms is dictated by a number of factors, the most important of which are degree of alcohol intake, length of time the individual has been using alcohol, and previous history of alcohol withdrawal.[11][12] Symptoms are also grouped together and classified:

- Alcohol hallucinosis: patients have transient visual, auditory, or tactile hallucinations, but are otherwise clear.[11]

- Withdrawal seizures: seizures occur within 48 hours of alcohol cessations and occur either as a single generalized tonic-clonic seizure or as a brief episode of multiple seizures.[13]

- Delirium tremens: hyperadrenergic state, disorientation, tremors, diaphoresis, impaired attention/consciousness, and visual and auditory hallucinations.[11]

Progression

.jpg.webp)

Six to 12 hours after the ingestion of the last drink, withdrawal symptoms such as shaking, headache, sweating, anxiety, nausea or vomiting may occur.[14] Twelve to 24 hours after cessation, the condition may progress to such major symptoms as confusion, hallucinations[14] (with awareness of reality), while less severe symptoms may persist and develop including tremor, agitation, hyperactivity and insomnia.[12]

At 12 to 48 hours following the last ethanol ingestion, the possibility of generalized tonic–clonic seizures should be anticipated, occurring in 3-5% of cases.[12] Meanwhile, none of the earlier withdrawal symptoms will typically have abated. Seizures carry the risk of major complications and death for individuals with an alcohol use disorder.[15][12]

Although the person's condition usually begins to improve after 48 hours, withdrawal symptoms sometimes continue to increase in severity and advance to the most severe stage of withdrawal, delirium tremens. This occurs in 5 to 20% of patients experiencing detoxification and one third of untreated cases,[13][12] which is characterized by hallucinations that are indistinguishable from reality, severe confusion, seizures, high blood pressure, and fever that can persist anywhere from 4 to 12 days.[14]

Protracted withdrawal

A protracted alcohol withdrawal syndrome occurs in many alcoholics when withdrawal symptoms continue beyond the acute withdrawal stage but usually at a subacute level of intensity and gradually decreasing with severity over time. This syndrome is sometimes referred to as the post-acute-withdrawal syndrome. Some withdrawal symptoms can linger for at least a year after discontinuation of alcohol. Symptoms can include a craving for alcohol, inability to feel pleasure from normally pleasurable things (known as anhedonia), clouding of sensorium, disorientation, nausea and vomiting or headache.[16]

Insomnia is a common protracted withdrawal symptom that persists after the acute withdrawal phase of alcohol. Insomnia has also been found to influence relapse rate. Studies have found that magnesium or trazodone can help treat the persisting withdrawal symptom of insomnia in recovering alcoholics. Insomnia can be difficult to treat in these individuals because many of the traditional sleep aids (e.g., benzodiazepine receptor agonists and barbiturate receptor agonists) work via a GABAA receptor mechanism and are cross-tolerant with alcohol. However, trazodone is not cross-tolerant with alcohol.[17][18][19] The acute phase of the alcohol withdrawal syndrome can occasionally be protracted. Protracted delirium tremens has been reported in the medical literature as a possible but unusual feature of alcohol withdrawal.[20]

Pathophysiology

Chronic use of alcohol leads to changes in brain chemistry especially in the GABAergic system. Various adaptations occur such as changes in gene expression and down regulation of GABAA receptors. During acute alcohol withdrawal, changes also occur such as upregulation of alpha4 containing GABAA receptors and downregulation of alpha1 and alpha3 containing GABAA receptors. Neurochemical changes occurring during alcohol withdrawal can be minimized with drugs which are used for acute detoxification. With abstinence from alcohol and cross-tolerant drugs these changes in neurochemistry may gradually return towards normal.[21][22] Adaptations to the NMDA system also occur as a result of repeated alcohol intoxication and are involved in the hyper-excitability of the central nervous system during the alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Homocysteine levels, which are elevated during chronic drinking, increase even further during the withdrawal state, and may result in excitotoxicity.[23] Alterations in ECG (in particular an increase in QT interval) and EEG abnormalities (including abnormal quantified EEG) may occur during early withdrawal.[23] Dysfunction of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and increased release of corticotropin-releasing hormone occur during both acute as well as protracted abstinence from alcohol and contribute to both acute and protracted withdrawal symptoms. Anhedonia/dysphoria symptoms, which can persist as part of a protracted withdrawal, may be due to dopamine underactivity.[24]

Kindling

Kindling is a phenomenon where repeated alcohol detoxifications leads to an increased severity of the withdrawal syndrome. For example, binge drinkers may initially experience no withdrawal symptoms, but with each period of alcohol use followed by cessation, their withdrawal symptoms intensify in severity and may eventually result in full-blown delirium tremens with convulsive seizures. Alcoholics who experience seizures during detoxification are more likely to have had previous episodes of alcohol detoxification than patients who did not have seizures during withdrawal. In addition, people with previous withdrawal syndromes are more likely to have more medically complicated alcohol withdrawal symptoms.

Kindling can cause complications and may increase the risk of relapse, alcohol-related brain damage and cognitive deficits. Chronic alcohol misuse and kindling via multiple alcohol withdrawals may lead to permanent alterations in the GABAA receptors.[25] The mechanism behind kindling is sensitization of some neuronal systems and desensitization of other neuronal systems which leads to increasingly gross neurochemical imbalances. This in turn leads to more profound withdrawal symptoms including anxiety, convulsions and neurotoxicity.[26]

Binge drinking is associated with increased impulsivity, impairments in spatial working memory and impaired emotional learning. These adverse effects are believed to be due to the neurotoxic effects of repeated withdrawal from alcohol on aberrant neuronal plasticity and cortical damage. Repeated periods of acute intoxication followed by acute detoxification has profound effects on the brain and is associated with an increased risk of seizures as well as cognitive deficits. The effects on the brain are similar to those seen in alcoholics who have detoxified repeatedly but not as severe as in alcoholics who have no history of prior detox. Thus, the acute withdrawal syndrome appears to be the most important factor in causing damage or impairment to brain function. The brain regions most sensitive to harm from binge drinking are the amygdala and prefrontal cortex.[27]

People in adolescence who experience repeated withdrawals from binge drinking show impairments of long-term nonverbal memory. Alcoholics who have had two or more alcohol withdrawals show more frontal lobe cognitive dysfunction than those who have experienced one or no prior withdrawals. Kindling of neurons is the proposed cause of withdrawal-related cognitive damage. Kindling from repeated withdrawals leads to accumulating neuroadaptive changes. Kindling may also be the reason for cognitive damage seen in binge drinkers.[28]

Diagnosis

Many hospitals use the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol (CIWA) protocol in order to assess the level of withdrawal present and therefore the amount of medication needed.[11] When overuse of alcohol is suspected but drinking history is unclear, testing for elevated values of carbohydrate-deficient transferrin or gammaglutamyl transferase can help make the diagnosis of alcohol overuse and dependence more clear. The CIWA has also been shortened (now called the CIWA-Ar), while retaining its validity and reliability, to help assess patients more efficiently due to the life-threatening nature of alcohol withdrawal.[29]

Other conditions that may present similarly include benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome (a condition also mainly caused by GABAA receptor adaptation).

Treatment

Benzodiazepines are effective for the management of symptoms as well as the prevention of seizures.[30] Certain vitamins are also an important part of the management of alcohol withdrawal syndrome. In those with severe symptoms inpatient care is often required.[31] In those with lesser symptoms treatment at home may be possible with daily visits with a health care provider.[31]

Benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepines are the most commonly used medication for the treatment of alcohol withdrawal and are generally safe and effective in suppressing symptoms of alcohol withdrawal.[32] This class of medication is generally effective in symptoms control, but need to be used carefully. Although benzodiazepines have a long history of successfully treating and preventing withdrawal, there is no consensus on the ideal one to use. The most commonly used agents are long-acting benzodiazepines, such as chlordiazepoxide and diazepam. These are believed to be superior to other benzodiazepines for treatment of delirium and allow for longer periods between doses. However, benzodiazepines with intermediate half-lives like lorazepam may be safer in people with liver problems.[33] Benzodiazepines showed a protective benefit against alcohol withdrawal symptoms, in particular seizure, compared to other common methods of treatment.[34]

The primary debate between use of long-acting benzodiazepines and short-acting is that of ease of use. Longer-acting drugs, such as diazepam, can be administered less frequently. However, evidence does exist that "symptom-triggered regimens" such as those used when treating with lorazepam, are as safe and effective, but have decreased treatment duration and medication quantity used.[33]

Although benzodiazepines are very effective at treating alcohol withdrawal, they should be carefully used. Benzodiazepines should only be used for brief periods in alcoholics who are not already dependent on them, as they share cross tolerance with alcohol. There is a risk of replacing an alcohol addiction with benzodiazepine dependence or adding another addiction. Furthermore, disrupted GABA benzodiazepine receptor function is part of alcohol dependence and chronic benzodiazepines may prevent full recovery from alcohol induced mental effects.[35][36] The combination of benzodiazepines and alcohol can amplify the adverse psychological effects of each other causing enhanced depressive effects on mood and increase suicidal actions and are generally contraindicated except for alcohol withdrawal.[37]

Vitamins

Alcoholics are often deficient in various nutrients, which can cause severe complications during alcohol withdrawal, such as the development of Wernicke syndrome. To help to prevent Wernicke syndrome, these individuals should be administered a multivitamin preparation with sufficient quantities of thiamine and folic acid. During alcohol withdrawal, the prophylactic administration of thiamine, folic acid, and pyridoxine intravenously is recommended before starting any carbohydrate-containing fluids or food. These vitamins are often combined into a banana bag for intravenous administration.[38]

Anticonvulsants

Very limited evidence indicates that topiramate or pregabalin may be useful in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome.[39] Limited evidence supports the use of gabapentin or carbamazepine for the treatment of mild or moderate alcohol withdrawal as the sole treatment or as combination therapy with other medications; however, gabapentin does not appear to be effective for treatment of severe alcohol withdrawal and is therefore not recommended for use in this setting.[39][40] A 2010 Cochrane review similarly reported that the evidence to support the role of anticonvulsants over benzodiazepines in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal is not supported.[41] Paraldehyde combined with chloral hydrate showed superiority over chlordiazepoxide with regard to life-threatening side effects and carbamazepine may have advantages for certain symptoms.[41] Long term anticonvulsant medications are not usually recommended in those who have had prior seizures due to withdrawal.[42]

Prevention of further drinking

There are three medications used to help prevent a return to drinking: naltrexone, acamprosate, and disulfiram. They are used after withdrawal has occurred.[43]

Other

Clonidine may be used in combination with benzodiazepines to help some of the symptoms.[11] No conclusions can be drawn concerning the efficacy or safety of baclofen for alcohol withdrawal syndrome due to the insufficiency and low quality of the evidence.[44]

Antipsychotics, such as haloperidol, are sometimes used in addition to benzodiazepines to control agitation or psychosis.[11] Antipsychotics may potentially worsen alcohol withdrawal as they lower the seizure threshold. Clozapine, olanzapine, or low-potency phenothiazines (such as chlorpromazine) are particularly risky; if used, extreme caution is required.[45]

While intravenous ethanol could theoretically be used, evidence to support this use, at least in those who are very sick, is insufficient.[46]

Hypertension is common, and some doctors also prescribe beta blockers during withdrawal.

Prognosis

Failure to manage the alcohol withdrawal syndrome appropriately can lead to permanent brain damage or death.[47] It has been proposed that brain damage due to alcohol withdrawal may be prevented by the administration of NMDA antagonists, calcium antagonists, and glucocorticoid antagonists.[48]

References

- National Clinical Guideline Centre (2010). "2 Acute Alcohol Withdrawal". Alcohol Use Disorders: Diagnosis and Clinical Management of Alcohol-Related Physical Complications (No. 100 ed.). London: Royal College of Physicians (UK). Archived from the original on 31 January 2014. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- Simpson SA, Wilson MP, Nordstrom K (September 2016). "Psychiatric Emergencies for Clinicians: Emergency Department Management of Alcohol Withdrawal". The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 51 (3): 269–73. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.03.027. PMID 27319379.

- Schuckit MA (November 2014). "Recognition and management of withdrawal delirium (delirium tremens)". The New England Journal of Medicine. 371 (22): 2109–13. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1407298. PMID 25427113. S2CID 205116954.

- Liu, Grant T.; Volpe, Nicholas J.; Galetta, Steven L. (1 January 2019), Liu, Grant T.; Volpe, Nicholas J.; Galetta, Steven L. (eds.), "12 - Visual Hallucinations and Illusions", Liu, Volpe, and Galetta's Neuro-Ophthalmology (Third Edition), Elsevier, pp. 395–413, ISBN 978-0-323-34044-1, retrieved 12 June 2023

- Helmus, Christian; Spahn, James G. (September 1974). "Delirium Tremens in Head and Neck Surgery". The Laryngoscope. 84 (9): 1479–1488. doi:10.1288/00005537-197409000-00004. ISSN 0023-852X. PMID 4412722. S2CID 28374619.

- Martin SC (2014). The SAGE Encyclopedia of Alcohol: Social, Cultural, and Historical Perspectives. SAGE Publications. p. Alcohol Withdrawal Scale. ISBN 9781483374383. Archived from the original on 22 October 2016.

- Kissin B, Begleiter H (2013). The Biology of Alcoholism: Volume 3: Clinical Pathology. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 192. ISBN 9781468429374. Archived from the original on 22 October 2016.

- Theisler, Charles (17 May 2022), "Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome", Adjuvant Medical Care, New York: CRC Press, pp. 6–7, doi:10.1201/b22898-7, ISBN 9781003291381, retrieved 28 September 2022

- Rahman, Abdul; Paul, Manju (2022), "Delirium Tremens", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 29489272, retrieved 9 February 2022

- Muncie HL, Yasinian Y, Oge' L (November 2013). "Outpatient management of alcohol withdrawal syndrome". American Family Physician. 88 (9): 589–95. PMID 24364635.

- Bayard M, McIntyre J, Hill KR, Woodside J (March 2004). "Alcohol withdrawal syndrome". American Family Physician. 69 (6): 1443–50. PMID 15053409. Archived from the original on 16 October 2008.

- Perry, Elizabeth C. (30 April 2014). "Inpatient Management of Acute Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome". CNS Drugs. 28 (5): 401–410. doi:10.1007/s40263-014-0163-5. ISSN 1172-7047. PMID 24781751. S2CID 42958201.

- Manasco A, Chang S, Larriviere J, Hamm LL, Glass M (November 2012). "Alcohol withdrawal". Southern Medical Journal. 105 (11): 607–12. doi:10.1097/smj.0b013e31826efb2d. PMID 23128805. S2CID 25769989.

- "Alcohol Withdrawal: Symptoms of Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome". WebMD. WebMD, LLC. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- McKeon, A.; Frye, M. A.; Delanty, Norman (1 August 2008). "The alcohol withdrawal syndrome". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 79 (8): 854–862. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2007.128322. ISSN 0022-3050. PMID 17986499. S2CID 2139796.

- Martinotti G, Di Nicola M, Reina D, Andreoli S, Focà F, Cunniff A, et al. (2008). "Alcohol protracted withdrawal syndrome: the role of anhedonia". Substance Use & Misuse. 43 (3–4): 271–84. doi:10.1080/10826080701202429. PMID 18365930. S2CID 25872623.

- Hornyak M, Haas P, Veit J, Gann H, Riemann D (November 2004). "Magnesium treatment of primary alcohol-dependent patients during subacute withdrawal: an open pilot study with polysomnography". Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 28 (11): 1702–9. doi:10.1097/01.ALC.0000145695.52747.BE. PMID 15547457.

- Le Bon O, Murphy JR, Staner L, Hoffmann G, Kormoss N, Kentos M, et al. (August 2003). "Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy of trazodone in alcohol post-withdrawal syndrome: polysomnographic and clinical evaluations". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 23 (4): 377–83. doi:10.1097/01.jcp.0000085411.08426.d3. PMID 12920414. S2CID 33686593.

- Borras L, de Timary P, Constant EL, Huguelet P, Eytan A (November 2006). "Successful treatment of alcohol withdrawal with trazodone". Pharmacopsychiatry. 39 (6): 232. doi:10.1055/s-2006-951385. PMID 17124647. S2CID 260250503.

- Miller FT (March–April 1994). "Protracted alcohol withdrawal delirium". Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 11 (2): 127–30. doi:10.1016/0740-5472(94)90029-9. PMID 8040915.

- Sanna E, Mostallino MC, Busonero F, Talani G, Tranquilli S, Mameli M, et al. (December 2003). "Changes in GABA(A) receptor gene expression associated with selective alterations in receptor function and pharmacology after ethanol withdrawal". The Journal of Neuroscience. 23 (37): 11711–24. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-37-11711.2003. PMC 6740939. PMID 14684873.

- Idemudia SO, Bhadra S, Lal H (June 1989). "The pentylenetetrazol-like interoceptive stimulus produced by ethanol withdrawal is potentiated by bicuculline and picrotoxinin". Neuropsychopharmacology. 2 (2): 115–22. doi:10.1016/0893-133X(89)90014-6. PMID 2742726.

- Hughes JR (June 2009). "Alcohol withdrawal seizures". Epilepsy & Behavior. 15 (2): 92–7. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.02.037. PMID 19249388. S2CID 20197292.

- Heilig M, Egli M, Crabbe JC, Becker HC (April 2010). "Acute withdrawal, protracted abstinence and negative affect in alcoholism: are they linked?". Addiction Biology. 15 (2): 169–84. doi:10.1111/j.1369-1600.2009.00194.x. PMC 3268458. PMID 20148778.

- Malcolm RJ (2003). "GABA systems, benzodiazepines, and substance dependence". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 64 (Suppl 3): 36–40. PMID 12662132.

- Becker HC (1998). "Kindling in Alcohol Withdrawal" (PDF). Alcohol Health & Research World. 22 (1): 25–33. PMC 6761822. PMID 15706729. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 December 2010.

- Stephens DN, Duka T (October 2008). "Review. Cognitive and emotional consequences of binge drinking: role of amygdala and prefrontal cortex". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 363 (1507): 3169–79. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0097. PMC 2607328. PMID 18640918.

- Courtney KE, Polich J (January 2009). "Binge drinking in young adults: Data, definitions, and determinants". Psychological Bulletin. 135 (1): 142–56. doi:10.1037/a0014414. PMC 2748736. PMID 19210057.

- Sullivan JT, Sykora K, Schneiderman J, Naranjo CA, Sellers EM (November 1989). "Assessment of alcohol withdrawal: the revised clinical institute withdrawal assessment for alcohol scale (CIWA-Ar)". British Journal of Addiction. 84 (11): 1353–7. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.489.341. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb00737.x. PMID 2597811.

- Amato L, Minozzi S, Vecchi S, Davoli M (March 2010). Amato L (ed.). "Benzodiazepines for alcohol withdrawal". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3 (3): CD005063. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005063.pub3. PMID 20238336.

- Muncie HL, Yasinian Y, Oge' L (November 2013). "Outpatient management of alcohol withdrawal syndrome". American Family Physician. 88 (9): 589–95. PMID 24364635.

- Bird RD, Makela EH (January 1994). "Alcohol withdrawal: what is the benzodiazepine of choice?". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 28 (1): 67–71. doi:10.1177/106002809402800114. PMID 8123967. S2CID 24312761.

- McKeon A, Frye MA, Delanty N (August 2008). "The alcohol withdrawal syndrome". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 79 (8): 854–62. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2007.128322. PMID 17986499. S2CID 2139796.

- Amato L, Minozzi S, Davoli M, et al. (Cochrane Drugs and Alcohol Group) (June 2011). "Efficacy and safety of pharmacological interventions for the treatment of the Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011 (6): CD008537. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008537.pub2. PMC 7173734. PMID 21678378.

- Toki S, Saito T, Nabeshima A, Hatta S, Watanabe M, Takahata N (February 1996). "Changes in GABAA receptor function and cross-tolerance to ethanol in diazepam-dependent rats". Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 20 (1 Suppl): 40A–44A. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01726.x. PMID 8659687.

- Rassnick S, Krechman J, Koob GF (April 1993). "Chronic ethanol produces a decreased sensitivity to the response-disruptive effects of GABA receptor complex antagonists". Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 44 (4): 943–50. doi:10.1016/0091-3057(93)90029-S. PMID 8385785. S2CID 5909253.

- Ziegler PP (August 2007). "Alcohol use and anxiety". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 164 (8): 1270, author reply 1270–1. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07020291. PMID 17671296. Archived from the original on 12 June 2011.

- Myrick H, Anton RF (1998). "Treatment of Alcohol Withdrawal" (PDF). Alcohol Health & Research World. 22 (1): 38–43. PMC 6761817. PMID 15706731. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 December 2010.

- Hammond CJ, Niciu MJ, Drew S, Arias AJ (April 2015). "Anticonvulsants for the treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome and alcohol use disorders". CNS Drugs. 29 (4): 293–311. doi:10.1007/s40263-015-0240-4. PMC 5759952. PMID 25895020.

- Leung JG, Hall-Flavin D, Nelson S, Schmidt KA, Schak KM (August 2015). "The role of gabapentin in the management of alcohol withdrawal and dependence". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy (Review). 49 (8): 897–906. doi:10.1177/1060028015585849. PMID 25969570. S2CID 19857498.

- Minozzi S, Amato L, Vecchi S, Davoli M (March 2010). Minozzi S (ed.). "Anticonvulsants for alcohol withdrawal". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3 (3): CD005064. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005064.pub3. PMID 20238337. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 January 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2010.

- "American Epilepsy Society Choosing Wisely". www.choosingwisely.org. 14 August 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- "Acamprosate: A New Medication for Alcohol Use Disorders" (PDF). 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- Liu, Jia; Wang, Lu-Ning (20 August 2017). "Baclofen for alcohol withdrawal". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 8 (8): CD008502. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008502.pub5. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6483686. PMID 28822350.

- Ebadi M (23 October 2007). "Alphabetical presentation of drugs". Desk Reference for Clinical Pharmacology (2nd ed.). USA: CRC Press. p. 512. ISBN 978-1-4200-4743-1.

- Hodges B, Mazur JE (November 2004). "Intravenous ethanol for the treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome in critically ill patients". Pharmacotherapy. 24 (11): 1578–85. doi:10.1592/phco.24.16.1578.50945. PMID 15537562. S2CID 19242952.

- Hanwella R, de Silva V (June 2009). "Treatment of alcohol dependence". The Ceylon Medical Journal. 54 (2): 63–5. doi:10.4038/cmj.v54i2.877. PMID 19670554.

- Hunt WA (November–December 1993). "Are binge drinkers more at risk of developing brain damage?". Alcohol. 10 (6): 559–61. doi:10.1016/0741-8329(93)90083-Z. PMID 8123218.

- Gitlow S (1 October 2006). Substance Use Disorders: A Practical Guide (2nd ed.). USA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. pp. 95–96. ISBN 978-0-7817-6998-3.

- Durazzo TC, Meyerhoff DJ (May 2007). "Neurobiological and neurocognitive effects of chronic cigarette smoking and alcoholism". Frontiers in Bioscience. 12 (8–12): 4079–100. doi:10.2741/2373. PMID 17485360. Archived from the original on 25 May 2011.

External links

- CIWA-Ar for Alcohol Withdrawal

- Alcohol Detox Guidelines Example Archived 19 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine