Eucalyptus camaldulensis

Eucalyptus camaldulensis, commonly known as the river red gum,[3] is a species of flowering plant in the family Myrtaceae, and is endemic to Australia. It is a tree with smooth white or cream-coloured bark, lance-shaped or curved adult leaves, flower buds in groups of seven or nine, white flowers and hemispherical fruit with the valves extending beyond the rim. A familiar and iconic tree, it is seen along many watercourses across inland Australia, providing shade in the extreme temperatures of central Australia.

| River red gum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Eucalyptus camaldulensis in the Wonga Wetlands, NSW | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Myrtales |

| Family: | Myrtaceae |

| Genus: | Eucalyptus |

| Species: | E. camaldulensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Eucalyptus camaldulensis | |

Description

Eucalyptus camaldulensis is a tree that typically grows to a height of 20 metres (66 ft) but sometimes to 45 metres (148 ft) and often does not develop a lignotuber. The bark is smooth white or cream-coloured with patches of yellow, pink or brown. There are often loose, rough slabs of bark near the base. The juvenile leaves are lance-shaped, 80–180 mm (3.1–7.1 in) long and 13–25 mm (0.51–0.98 in) wide. Adult leaves are lance-shaped to curved, the same dull green or greyish green colour on both sides, 50–300 mm (2.0–11.8 in) long and 7–32 mm (0.28–1.26 in) wide on a petiole 8–33 mm (0.31–1.30 in) long. The flower buds are arranged in groups of seven, nine or sometimes eleven, in leaf axils on a peduncle 5–28 mm (0.20–1.10 in) long, the individual flowers on pedicels 2–10 mm (0.079–0.394 in) long. Mature buds are oval to more or less spherical, green to creamy yellow, 6–9 mm (0.24–0.35 in) long and 4–6 mm (0.16–0.24 in) wide with a prominently beaked operculum 3–7 mm (0.12–0.28 in) long. Flowering mainly occurs in summer and the flowers are white. The fruit is a woody, hemispherical capsule 2–5 mm (0.079–0.197 in) long and 4–10 mm (0.16–0.39 in) wide on a pedicel 3–12 mm (0.12–0.47 in) long with the valves raised above the rim.[3][4][5][6][7]

The limbs of river red gums, sometimes whole trees, often fall without warning so that camping or picnicking near them is dangerous, especially if a tree has dead limbs or the tree is under stress.[8]

Taxonomy and naming

Eucalyptus camaldulensis was first formally described in 1832 by Friedrich Dehnhardt who published the description in Catalogus Plantarum Horti Camaldulensis.[9][10]

Seven subspecies of E. camaldulensis have been described and accepted by the Australian Plant Census. The most variable character is the shape and size of the operculum, followed by the arrangement of the stamens in the mature buds and the density of veins visible in the leaves. The subspecies are:[4]

- Eucalyptus camaldulensis subsp. acuta Ian Brooker & M.W.McDonald[11] has mature flower buds with a pointed operculum 6–9 mm (0.24–0.35 in) long and erect stamens and broadly lance-shaped or egg-shaped juvenile leaves;

- Eucalyptus camaldulensis subsp. arida Ian Brooker & M.W.McDonald[12] has bluish green adult leaves with only a few veins and mature flowers buds with a curved to rounded operculum 3–7 mm (0.12–0.28 in) long;

- Eucalyptus camaldulensis Dehnh. subsp. camaldulensis[13] has a strongly beaked operculum, incurved or irregularly bent stamens and narrow lance-shaped juvenile leaves;

- Eucalyptus camaldulensis subsp. minima Ian Brooker & M.W.McDonald[14] has mature flower buds that are small with a conical operculum 2–4 mm (0.079–0.157 in) long and broad juvenile leaves that are usually covered with a powdery bloom;

- Eucalyptus camaldulensis subsp. obtusa (Blakely) Ian Brooker & M.W.McDonald[15] has white, powdery bark in some months and mature flower buds with a curved, conical operculum 4–7 mm (0.16–0.28 in) long;

- Eucalyptus camaldulensis subsp. refulgens Ian Brooker & M.W.McDonald[16] has very glossy green adult leaves with a dense network of veins;

- Eucalyptus camaldulensis subsp. simulata Ian Brooker & Kleinig.[17] has a horn-shaped operculum 9–16 mm (0.35–0.63 in) long.

The specific epithet (camaldulensis) is a reference to a private estate garden (L'Hortus Camaldulensis di Napoli) near the Camaldoli monastery in Naples, where Frederick Dehnhardt was the chief gardener.[4] The type specimen was grown in the gardens from seed presumably collected in 1817 near Condobolin by Allan Cunningham,[18] and was grown there for about one hundred years before being removed in the 1920s.[19] Herbarium specimen of the holotype is deposited in the herbarium of Natural History Museum of Vienna.[20]

Although Dehnhardt was the first to formally describe E. camaldulensis, his book was largely unknown to the botanical community. In 1847 Diederich von Schlechtendal gave the species the name Eucalyptus rostrata but the name was illegitimate (a nomen illegitimum) because it had already been applied by Cavanilles to a different species (now known as Eucalyptus robusta).[21] In the 1850s, Ferdinand von Mueller labelled some specimens of river red gum as Eucalyptus longirostris and in 1856 Friedrich Miquel published a description of von Mueller's specimens, formalising the name E. longirostris.[22] Finally in 1934, William Blakely recognised Dehnhardt's priority and the name E. camaldulensis for river red gum was accepted.[19]

Northern Territory Aboriginal names for this species are:[23]

- aper (Alyawarr, Anmatyerr), aper or per (Eastern Arrernte), apere (Kaytetye), aylpele (Pintupi Luritja), itara, ngapiri, pipalya, yitara (Pitjantjatjara) apara, itara, piipalya, (Waramangu), kunjumarra (Warlpiri), kunjumarra and ngapiri (Western Arrernte).

Dimilan is the name of this tree in the Miriwoong language of the Kimberley.[24]

Distribution and habitat

Eucalyptus camaldulensis has the widest natural distribution of any eucalyptus species. It is commonly found along waterways and there are only a few locations where the species is found away from a watercourse.[25][26]

- Subspecies acuta is common along rivers from south of Cape York Peninsula in Queensland to the north west slopes and plains of New South Wales but is absent from coastal areas and the arid inland.

- Subspecies arida has the widest distribution of the subspecies and is found in all mainland states except Victoria. It grows in arid regions but only where there is sufficient subsoil moisture.[4][27]

- Subspecies camaldulensis is the dominant eucalypt along the Murray-Darling river system and its tributaries. It also occurs on the Eyre and Yorke Peninsulas and Kangaroo Island in South Australia and in some locations along the Hunter River in New South Wales. It is the only subspecies in coastal Victoria.[4][28]

- Subspecies minima is endemic to South Australia, where it grows in the northern Flinders Ranges and the northern Eyre Peninsula.[4]

- Subspecies obtusa is endemic to tropical northern Australia, including parts of the Kimberley, the Top End and the Gulf of Carpentaria hinterland as far east as the Gilbert River, Queensland in Queensland.[4]

- Subspecies refulgens is endemic to the Pilbara-Gascoyne-Carnarvon region, along rivers flowing westwards, including along some of the tributaries of the upper Murchison River.[4]

- Subspecies simulata is mainly restricted to some rivers on Cape York Peninsula, but with some populations further south.[4]

Ecology

The species can be found along the banks of watercourses, as well as the floodplains of those watercourses. Due to the proximity to these watercourses, river red gum is subject to regular flooding in its natural habitat. River red gum prefers soils with clay content. The trees not only rely on rainfall but also on regular flooding, since flooding recharges the sub-soil with water.[29]

The association of the river red gum with water makes the tree a natural habitat choice, indeed sometimes the only choice in drier areas, for other species. The trees provide a breeding habitat for fish during the flooding season, which also benefits aquatic bird life that depend on fish as a food source during their own breeding season. Wilson,[26] who examined the management of river red gums in NSW, suggests shelter is provided for fish in rivers and streams by fallen branches from the river red gum. The "snags" formed when river red gums fall into rivers such as the Glenelg, are an important part of river ecosystems, and vital habitat and breeding sites for native fish like river blackfish. Unfortunately most snags have been removed from these rivers, beginning in the 1850s, due to river-improvement strategies designed to prevent hazards to navigation, reduce damage to in-stream structures, rejuvenate or scour channels, and increase hydraulic capacity to reduce flooding.[30] However, the Murray–Darling Basin Commission has recognised the importance of snags as aquatic habitat, and a moratorium on their removal from the Murray River has been recommended.[31]

Hollows start to form at around 120–180 years of age, creating habitat for many wildlife species, including a range of breeding and roosting animals such as bats, carpet pythons, and birds.[26] The dense foliage of the tree also provides shade and shelter from the sun in drier areas.

The superb parrot, a threatened species, is amongst the bird species that nest in the river red gum.[32]

River red gums contribute to the provision of nutrients and energy for other species through leaf and insect fall. This is especially important to the ecology in areas of low nutrients.[26] The tree's preferred habitat of floodplains and watercourses also gives it the role of flood mitigator, which slows silt runoff.

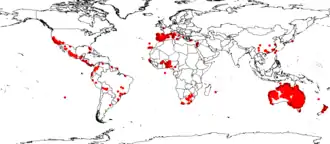

Weed

The global weed compendium[33] lists E. camaldulensis as a weed in Portugal, Canary Islands, South Africa, Spain, Bangladesh, the United States, Ecuador, the Galapagos and other countries.[33] The species, while native to parts of Western Australia, has become naturalised via garden escapees and introduction as a restoration plant; they are the subject of weed management programs.[7] Its ability to tolerate drought and soil salinity, together with its prolific seed production, and capacity to reproduce when very young, mean that it is highly adaptable, and it has been declared invasive in South Africa, California, Jamaica, Spain, and Hawaii[34]

Reproduction and dispersion

The flower begins as an "invaginated receptacle".[35] The operculum, or cap, protects the interior of the flower bud, as the male and female parts develop.

The male parts of the flower consist of the stamen, a slender filament, and the anther, two pollen sacs located at the top of the stamen. The anther sacs open into longitudinal slits to release their pollen. These filaments will extend to encircle the receptacle during flowering.

The female parts of the flower, the ovaries, are contained in ovary chambers. These chambers are separated from the receptacle containing the male parts by a disc. From the top of the ovaries a structure called the style extends into the receptacle, to form the stigma.

During flowering, pollen from the anthers can fall onto the stigma. This can occasionally lead to self-pollination, although the stigma does not become receptive until a few days after the operculum has been detached by the expanding stamens, and the flower's pollen has already been released.[36] Fertilisation will therefore occur with other flowers on the same tree or other flowers on a different tree. Insects, birds, and small mammals help in the pollination of other flowers.[35][36]

After flowering, the stamens will detach. The fruit is the part of the flower that remains after fertilisation, which enlarges, dries, and becomes woody. Triangular valves in the fruit will open, dispersing yellow, cuboid seeds. When seeds are shed from a tree, most fall onto the ground below the crown, with some seed carried by the wind and water. Dissemination occurs mostly in spring and summer,[29][37] while natural flooding occurs during winter and spring.[29] As the tree is inextricably linked with waterways, seed dispersion would logically be facilitated by floodwater. There is some contention in this theory, however, where the CSIRO describes an experiment that demonstrated seeds were found to sink after only 36 hours.[37] It would also seem that as the seeding and flooding do not entirely coincide, it could be inferred that the conditions for germination, such as damp soil and plenty of sunlight, are more important in the continuation of the species than seed dispersal by means of floodwater. Seeding during the flooding season would prevent desiccation of the seed, which is the main cause of a seed's failure to reproduce.[36] Despite this apparent evolutionary advantage of the species living near watercourses to avoid seed desiccation, many seeds will be produced within an E. camaldulensis forest before one will grow to its own reproducing stage. A gap in the forest must be available for the germinated seed to receive adequate sunlight.[36]

Formation of the Barmah red gum forests

The formation of the noted Barmah red gum forests is due to a relatively recent geological event in the Murray-Darling Basin involving the Cadell Fault.

River red gum seeds germinate readily after floods and require regular spring floods throughout their life to survive. In the Murray-Darling Basin, such floods are now rare due to river regulation for irrigation, and as a result, 75% of River red gums in the lower Murray are stressed, dead or dying.

The largest remaining stand of river red gum is the 65,000 ha (160,000 acres) Barmah-Millewa forest straddling the border of Victoria and New South Wales, due north of Melbourne. It retains enormous cultural significance to the Indigenous traditional owners, the Yorta Yorta Nation. Like many stands of river red gum, the Barmah-Millewa has been drastically altered by over 100 years of timber harvesting. There is a paucity of old hollow-bearing trees which provide habitat for rare and threatened fauna such as the superb parrot, brush-tailed phascogale and inland carpet python. (Though these species are currently not under threat.) The increasing scale of logging machinery is creating large areas of intensive soil disturbance and bare earth, which is likely to increase weed invasion and increase the likelihood of the extinction of rare understorey plants.

About 25,000 years ago, displacement occurred along the Cadell fault, raising the eastern edge of the fault (which runs north-south) 8–12 metres (26–39 ft) above the floodplain. This created a complex series of events. A section of the original Murray River channel immediately behind the fault was abandoned, and exists today as an empty channel known as Green Gully. The Goulburn River was dammed by the southern end of the fault to create a natural lake. The Murray River flowed to the north around the Cadell Fault, creating the channel of the Edward River which exists today and through which much of the Murray River's waters still flow. Then the natural dam on the Goulburn River failed, the lake drained, and the Murray River abruptly deviated to the south and started to flow through the smaller Goulburn River channel, creating "The Barmah Choke" and "The Narrows" (where the river channel is unusually narrow), before entering into the proper Murray River channel again.

The primary result of the Cadell Fault however is that the west-flowing water of the Murray River strikes the north-south running fault and diverts both north and south around the fault in the two main channels (Edwards and ancestral Goulburn) as well as a fan of small streams, and regularly floods a large amount of low-lying country in the area. These conditions are perfect for river red gums, which rapidly formed forests in the area. Thus the displacement of the Cadell Fault 25,000 years BP led directly to the formation of the Barmah river red gum forests.

Uses

Use in horticulture

E. camaldulensis readily germinates from both fresh seed and seed stored in cool dry conditions. It quickly toughens up and can withstand drought even whilst in forestry tubes. It makes an excellent bonsai and will readily regrow both from the base and from epicormic buds.

Timber

Red gum is so named for its brilliant red wood, which can range from a light pink through to almost black, depending on the age and weathering. It is somewhat brittle and is often cross-grained, making hand working difficult. Traditionally used in rot resistant applications like stumps, fence posts and sleepers, more recently it has been recognised in craft furniture for its spectacular deep red colour and typical fiddleback figure. It needs careful selection, as it tends to be quite reactive to changes in humidity (moves about a lot in service). It is quite hard, dense (about 900 kg/m3 (1,500 lb/cu yd)), can take a fine polish and carves well. It is a popular timber for wood turners, particularly if old and well-seasoned.

It is also popular for use as firewood. Significant amounts of Victoria and NSW's firewood comes from red gums in the Barmah forest.

The wood makes fine charcoal, and is successfully used in Brazil for iron and steel production. In addition, this plant is used for beekeeping in Brazil and Australia. Recently, it has been used to produce decks (Patagonian cherry) and wooden floors (Andean cherry).

It is one of the most widely planted eucalypts in the world (c. 5,000 km2 (1,900 sq mi) planted) (NAS, 1980a). Plantations occur in Argentina, Arizona, Brazil, Burkina Faso, California, Egypt, Kenya, Morocco, Nepal, Nigeria, Pakistan, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Spain, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Tanzania, Uruguay, and Zimbabwe. The areas of significance to humans of Eucalyptus camaldulensis include agricultural, ecological, cultural, and recreational significance.

The speed of growth of the tree makes it a useful plantation timber. Apiarists also use the tree’s flowers for honey production. E. camaldulensis is important in supporting the ecology of its habitat through providing food, and shelter for breeding. Culturally, the species is an iconic part of Australia. Its leaves have appeared on Australian stamps[38] and is widely recognised due to its widespread range. The use of the waterways for seasonal recreation also occurs within the habitat of the river red gum, again due their fundamental link to watercourses and floodplains.[26]

An image of The Old Gum Tree was engraved for a stamp in 1936 to commemorate the centenary of foundation of South Australia.[39]

Population management

The predilection of the river red gum for waterways has been a successful evolutionary niche. This has resulted in a large population and range for the species, and so it is not considered endangered. Changes in its habitat, however, could be detrimental not just for the tree, but also for species that depend on the tree for their own survival. These changes include grazing, and water regulation for irrigation purposes. For example, grazing reduces the ability of the species to regenerate, as stock eat or trample the seedlings. However, grazing may aid regeneration by removing thick ground cover.[26]

In regards to water regulation, there are two problems. One is the timing of the water flow, and the other is the minimisation of natural flooding.

Regulation causes flooding to be decreased during the winter and spring months, and water more consistently flows during the summer and autumn months. Since the river red gum disperses its seed during spring, regulating the water may affect the species' ability to disperse using water as a dispersing agent, especially in floodplain red gum forests. Natural water run-off can also be affected, leaving some trees permanently flooded due to the build-up of water behind dams, or the permanent water flow. Neither can seeds germinate in constantly flooded areas.

Infrequent flooding due to water regulation provides inadequate water to recharge the floodplain subsoils that river red gums depend on. This will result in stunted tree growth, death of existing trees, and poor conditions for seed germination. Lack of flooding in floodplain areas will change the suitability of river red gum habitat as a breeding ground and food source for other species. Indeed, extinctions of some species have already occurred in river red gum habitats in the Murray-Darling catchment.[26]

It has been recognised since around the early 1980s that managing water more effectively would ensure the maintenance of river red gum habitat. Water management would include the removal of subsidies for irrigation, issuing water licenses, and the flooding of forests in suitable seasons.[29]

In popular culture

Examples of river red gums include:

- The Big Tree near Moulamein - one of the largest river red gums in the Riverina, with a circumference of 11.6 metres;[40]

- Cazneaux Tree - Photographed by Harold Cazneaux in the Spirit of Endurance;

- Separation Tree - Where celebrations were held when Victoria became a separate colony to New South Wales;

- The Old Gum Tree - Where the colony of South Australia was proclaimed;

- The Queen's Tree - Planted in Kings Park, Perth Western Australia in 1954 by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II on her first visit to Australia.

Galleries

Adult leaves

Adult leaves Buds

Buds Fruit

Fruit Seeds

Seeds Trunk bark

Trunk bark

- Examples of river red gums

A river red gum near Bolin Bolin Billabong on the Yarra River.

A river red gum near Bolin Bolin Billabong on the Yarra River. A view down the Murray River – every tree pictured is a river red gum.

A view down the Murray River – every tree pictured is a river red gum. A 700-year-old tree at the Wonga Wetlands, NSW.

A 700-year-old tree at the Wonga Wetlands, NSW. Many river red gums on the banks of the Barcoo River, south-west Queensland.

Many river red gums on the banks of the Barcoo River, south-west Queensland..jpg.webp) River red gums; the Murrumbidgee River in flood.

River red gums; the Murrumbidgee River in flood.

"The Queen's Tree", Kings Park, Perth, WA.

"The Queen's Tree", Kings Park, Perth, WA. A river red gum in a bend of the Murrumbidgee River near Hay, NSW.

A river red gum in a bend of the Murrumbidgee River near Hay, NSW.

See also

References

- CSIRO, 2004. Eucalyptus camaldulensis Dehnh. River Red Gum.

- Mackay, Norman and David Eastburn (eds) 1990. The Murray. Murray-Darling Basin Commission, Canberra. ISBN 1-875209-05-0.

References

- Fensham, R.; Laffineur, B.; Collingwood, T. (2019). "Eucalyptus camaldulensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T61909812A61909824. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T61909812A61909824.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- "Eucalyptus camaldulensis". Australian Plant Census. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- Brooker, M. Ian; Slee, Andrew. "Eucalyptus camaldulensis". Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- "Eucalyptus camaldulensis subsp. camaldulensis River red gum, Murray red gum". Euclid: Centre for Australian National Biodiversity Research. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- Hill, Ken. "Eucalyptus camaldulensis". Royal Botanic Garden Sydney. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- "Eucalyptus camaldulensis". State Herbarium of South Australia. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- "Eucalyptus camaldulensis". FloraBase. Western Australian Government Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions.

- "Tree risk". Parks Victoria. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- "Eucalyptus camaldulensis". APNI. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- Dehnhardt, Friedrich (1832). Catalogus Plantarum Horti Camaldulensis (2nd ed.). Naples. p. 20. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- "Eucalyptus camaldulensis subsp. acuta". Australian Plant Census. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- "Eucalyptus camaldulensis subsp. arida". Australian Plant Census. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- "Eucalyptus camaldulensis subsp. camaldulensis". Australian Plant Census. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- "Eucalyptus camaldulensis subsp. minima". Australian Plant Census. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- "Eucalyptus camaldulensis subsp. obtusa". Australian Plant Census. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- "Eucalyptus camaldulensis subsp. refulgens". Australian Plant Census. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- "Eucalyptus camaldulensis subsp. simulata". Australian Plant Census. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- Cleland, J. B. (1956). "Eucalyptus camaldulensis and E. longirostris (rostrata)". The Victorian Naturalist. 73: 10–14.

- Boland, D.J.; Brooker, M.I.H.; Chippendale, G.M.; Hall, N.; Hyland, B.P.M.; Johnston, R.D.; Kleinig, D.A. [in Spanish]; McDonald, M.W.; Turner, J.D. (2006). Forest Trees of Australia (5th ed.). Collingwood, VIC: CSIRO Publishing. p. 320. ISBN 0-643-06969-0.

- W 0003122 (mirror in JSTOR)

- "Eucalyptus rostrata Schltdl". APNI. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- "Eucalyptus longirostris F.Muell. ex Miq". APNI. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- "NT Flora Eucalyptus camaldulensis subsp. obtusa". Northern Territory Flora Online. Northern Territory Government. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- Miriwoong Woorlang Yawoorronga-woor - a Miriwoong Lexicon for all. Mirima Dawang Woorlab-gerring Language and Culture Centre. 2017.

- Colloff, Matthew (2014). Flooded Forest and Desert Creek]. CSIRO Publishing. ISBN 9780643109193.

- Wilson, N. (1995). The Flooded Gum Trees: Land Use and Management of River Red Gums in New South Wales. Sydney: Nature Conservation Council of New South Wales.

- "Eucalyptus camaldulensis subsp. arida". FloraBase. Western Australian Government Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions.

- Messina, Andre; Stajsic, Val. "Eucalyptus camaldulensis subsp. camaldulensis". Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- Dexter, B. D.; Rose, H. J.; Davies, N. (1986). "River regulation and associated forest management problems in the River Murray red gum forests". Australian Forestry. 49 (1): 16–27. doi:10.1080/00049158.1986.10674459.

- Gippel, C. J.; O'Neill, I.; Finlayson, B. L; Schnatz, I. (1996). "Hydraulic guidelines for the re-introduction and management of large woody debris in lowland rivers". Regulated Rivers: Research and Management. 12 (2–3): 223–36. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1646(199603)12:2/3<223::AID-RRR391>3.0.CO;2-#.

- Lawrence, B. W. (1991). Draft Fish Management Plan. Canberra: Murray–Darling Basin Commission.

- BirdLife International (2018). "Polytelis swainsonii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T22685072A130018368. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22685072A130018368.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- The Global Compendium of Weeds: Eucalyptus camaldulensis

- CABI Eucalyptus camaldulensis (red gum)

- Brooker, M. I. H.; Kleinig, D. A. (1990). Field Guide to Eucalypts. Vol. 1 South-eastern Australia. Sydney: Inkata Press.

- Penfold, A. R.; Willis, J. L. (1961). The Eucalypts. London: Leonard Hill.

- CSIRO (2005). "Eucalyptus camaldulensis Dehnh". CSIRO-Water for a Healthy Country. Retrieved 26 August 2005.

- Chippendale, G. M.; Johnston, R. D. (1969). Kelly, S. (ed.). Eucalypts (1st ed.). Melbourne: Nelson. ISBN 0-17-006221-X.

- "Proclamation Tree, SA, Eucalyptus camaldulensis". Australian Plants on Postage Stamps. Australian National Herbarium. Retrieved 10 December 2010.

- "The Big Tree". River Country Tourism. Retrieved 18 April 2020.