Euphronios

Euphronios (Greek: Εὐφρόνιος; c. 535 – after 470 BC) was an ancient Greek vase painter and potter, active in Athens in the late 6th and early 5th centuries BC. As part of the so-called "Pioneer Group," (a modern name given to a group of vase painters who were instrumental in effecting the change from black-figure to red-figure pottery), Euphronios was one of the most important artists of the red-figure technique. His works place him at the transition from Late Archaic to Early Classical art, and he is one of the first known artists in history to have signed his work.

General considerations

The discovery of Greek vase painters

In contrast to other artists, such as sculptors, no Ancient Greek literature sources refer specifically to vase painters. The copious literary tradition on the arts hardly mention pottery. Thus, reconstruction of Euphronios's life and artistic development—like that of all Greek vase painters—can only be derived from his works.

Modern scientific study of Greek pottery began near the end of the 18th century. Initially, interest focused on iconography. The discovery of the first signature of Euphronios in 1838 revealed that individual painters could be identified and named, so that their works might be ascribed to them. This led to an intensive study of painters' signatures, and by the late 19th century, scholars began to compile stylistic compendia.

The archaeologist John D. Beazley used these compendia as a starting point for his own work. He systematically described and catalogued thousands of Attic black-figure and red-figure vases and sherds, using the methods of the art historian Giovanni Morelli for the study of paintings. In three key volumes on Attic painters, Beazley achieved a taxonomy that remains mostly valid to this day. He listed all known painters (named or unnamed) who produced individual works of art which can always be unmistakably ascribed. Today, most painters are identified, though their names often remain unknown.

The situation in Athens at the end of the 6th century BC

Euphronios must have been born around 535 BC, when Athenian art and culture bloomed during the tyranny of Peisistratos. Most Attic pottery was then painted in the black-figure style. Much of the Athenian pottery production of that time was exported to Etruria. Most of the extant Attic pottery has been recovered as grave goods (excavated or looted) from Etruscan tombs.

At the time, vase painting received major new impulses from potters such as Nikosthenes and Andokides. The Andokides workshop began the production of red-figure pottery around 530 BC. Gradually, the new red-figure technique began to replace the older black-figure style. Euphronios was to become one of the most important representatives of early red-figure vase painting in Athens. Together with a few other contemporary young painters, modern scholarship counts him as part of the "Pioneer Group" of red-figure painting.

Apprenticeship in the workshop of Kachrylion

Euphronios appears to have started painting vases around 520 BC, probably under the tutelage of Psiax. Later, Euphronios himself was to have a major influence on the work of his erstwhile master, as well as on that of several other older painters. Later he worked in the workshop of the potter Kachrylion, under supervision of the painter Oltos.

His works from this early phase already show several of Euphronios' artistic characteristics: his tendency to paint mythological scenes, his preference for monumental compositions, but also for scenes from everyday life, and his careful rendering of muscles and movement. The latter aspects particularly indicate a close link with Psiax, who painted in a similar style. Apart from a few fragments, a bowl in London (E 41) and one in Malibu (77.AE.20) can be ascribed to this phase of his work.

The most important early vase, however, is a signed specimen depicting Sarpedon. It was only through the appearance of this vase on the international market that Euphronios' early works could be recognised and distinguished from the paintings of Oltos, who had previously been credited with some works by Euphronios. Although it later became common for painters to sign their best works, signatures were rarely used in black-figure and early red-figure painting.

Even Euphronios's earliest known works show a total control of the technical abilities necessary for red-figure vase painting. Similarly, a number of technical advances which were adopted as part of the standard red-figure technique can be first seen in his work. To render the depictions of human anatomy more plastic and realistic, he introduced the relief line and the use of diluted clay slip. Depending on how it is applied, the slip can acquire a range of colours between light yellow and dark brown during firing, thus multiplying the stylistic possibilities available to the artist. Euphronios's technical and artistic innovations were apparently quickly influential; pieces produced during his early period by other painters working for Kachrylion, and even by his former teachers Psiax and Oltos, show stylistic and technical aspects first seen in Euphronios's own work.

Although Kachylion's workshop only produced drinking bowls, and Euphronios continued to work for him into his maturity, simple bowls soon failed to satisfy his artistic impulse. He began to paint other vase types, probably working with different potters. The Villa Giulia holds two very early pelikes by him. Such medium-size vases offered more space for his figural paintings. A psykter now in Boston is also counted among his early work, as it strongly resembles the work of Oltos: stiff garment folds, almond-shaped eyes, a small protruding chin and ill-differentiated hands and feet. Alternatively, it could be a relatively careless work from a later phase.

Such problems in assigning Euphronios' works to the different periods of his activity recur for several of his vases. Although the general chronology and development of his work is well known, some of his works remain difficult to place precisely. For example, a chalice krater in the Antikensammlung Berlin, depicting young men exercising in the palaistra is often counted among his later works due to the vase shape. Nonetheless, it seems that in spite of the occurrence of some advanced methods (careful representation of musculature, the use of the relief line), the krater must be dated to an earlier phase, since it borrows some stylistic motifs from black-figure vase painting. These motifs include an ivy garland below the mouth, the fairly small image format and the stylistic similarity to the work of Oltos.

Euphronios and Euxitheos: Mature phase, years of mastery

Innovation and competition

Around 510 BC, probably seeking new media for his compositions, Euphronios entered the workshop of Euxitheos, a potter who was similarly engaged in experimenting with form and decor in his own work. The stylistic development of Euphronios's work during this period, during which both painter and potter attempted bold and influential experiments, permits a reconstruction of its chronological sequence with some certainty.

A partially preserved chalice krater from this period (Louvre G 110) is indicative of the degree to which Euphronios was aware of the influence of his artistic innovations. The front of the chalice shows a classic scene that he had already painted on a bowl around 520 BC : the fight between Heracles and the Nemean Lion. The back, however, depicts a bold and innovative double composition : above, a komos scene, with the participants of the dance drawn in extreme physical postures, and below, a figure viewed from behind, arms leaning backwards. The striking scene has been thought to be the reason that Euphronios signed the work. The signature is unique, as the artist uses the formula Euphronios egraphsen tade - "Euphronios has painted these things". The piece is a characteristic example of the Pioneer Group's work and shows how a single vase could make an individual contribution to the development of the form.

This drive for innovation led to a spirit of competition even within individual workshops. On an amphora in Munich, Euthymides, another Pioneer Group Painter, claims that he has painted a picture "as Euphronios never could have done". This phrase implies respect for the colleague's and rival's skill, as well as a contest with him. Similarly, a somewhat younger painter, Smikros, probably a pupil of Euphronios, created some very successful early works that directly plagiarised his master. The Getty Museum has a signed psykter by Smikros that depicts Euphronios wooing an ephebe named as Leagros. The name Leagros occurs frequently in kalos inscriptions by Euphronios.

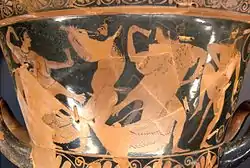

Herakles, Antaios and Sarpedon – the two masterpieces

A chalice krater with a depiction of Heracles and Antaios in combat is often considered one of Euphronios's masterpieces. The contrast between the barbarian Libyan giant Antaios and the civilised, well-groomed Greek hero is a striking reflection of the developing Greek self-image, and the anatomical precision of the struggling characters' bodies lends grace and power to the piece. The intensity of the work is increased by the presence of two female figures, whose statuesque appearance closes the image. During the restoration of the vase, an original outline sketch was found, showing that Euphronios initially had difficulties in depicting the dying giant's outstretched arm, but managed to overcome them while painting the scene.

The Sarpedon Krater or Euphronios Krater, created around 515 BC, is normally considered to be the apex of Euphronios' work. As on the well-known vase from his early phase, Euphronios sets Sarpedon at the centre of the composition. Following an order by Zeus, Thanatos and Hypnos carry Sarpedon's dead body from the battlefield. In the centre background is Hermes, here depicted in his role of accompanying the dead on their last voyage. The ensemble is flanked by two Trojan warriors staring straight ahead, apparently oblivious of the action that takes place between them. The figures are not only labelled with their names, but also with explanatory texts. The use of thin slip allowed Euphronios to deliberately use different shades of colour, rendering the scene especially lively. But the krater marks the peak of the artist's abilities not only in pictorial terms; the vase also represents a new achievement in the development of the red-figure style. The shape of the chalice krater had already been developed during the black-figure phase by the potter and painter Exekias, but Euxitheos's vase displays further innovations created specifically for the red-figure technique. By painting the handles, foot and lower body of the vase black, the space available for red-figure depictions is strictly limited. As is usual for Euphronios, the pictorial scene is framed by twisting curlicues. The painting itself is a classic example of the painter's work: strong, dynamic, detailed, anatomically accurate and with a strong hint of pathos. Both artists appear to have been aware of the quality of their work, as both painter and potter signed it. The krater is the only work by Euphronios to have survived in its entirety.

The back of the Sarpedon Krater shows a simple arming scene, executed more hastily as the massive krater's clay dried and rendered it less workable. This explicitly contemporary scene, depicting a group of anonymous youths arming themselves for war, is emblematic of the new realism in content as well as form which Euphronios brought to the red-figure technique. These scenes from everyday life, and the artistic conceit of pairing them with a mythological scene on the same piece, distinguish many of the pieces painted by Euphronios and those who followed him.

In addition to its unique archaeological and artistic status, the Sarpedon Krater played a pivotal role in the exposure and dismantling of a major antiquities smuggling network that traded in looted archaeological treasures and sold them on to major museums and collectors, including the Metropolitan Museum, the J. Paul Getty Museum in California, and Texan oil billionaire Nelson Bunker Hunt. The krater was one of a number of grave goods that were illegally unearthed in late 1971 when a gang of tombaroli (tomb robbers) led by Italian antiquities dealer Giacomo Medici looted a previously-undiscovered Etruscan tomb complex near Cerveteri, Italy. Medici subsequently sold the krater to American dealer Robert E. Hecht, who in turn negotiated its sale for US$1 million to the Metropolitan Museum, New York City, where it went on display from 1972. Over the next thirty years, a series of press investigations and a lengthy and extensive trans-national criminal investigation led by Italian authorities eventually smashed the smuggling ring, resulting in numerous prosecutions (including Medici, Hecht and Getty Museum curator Marion True), and the return to Italy of scores of looted antiquities illegally obtained by the Metropolitan, the Getty and other institutions. After lengthy negotiations, the Euphronios krater was formally returned to Italian ownership in February 2006, but remained on display as a loan to the Metropolitan Museum until its highly publicised repatriation to Italy in January 2008.[1]

Scenes from everyday life

Apart from mythological motifs, Euphronios also produced many pots incorporating scenes from everyday life. A chalice krater in the Staatliche Antikensammlungen at Munich depicts a symposium. Four men are lying on couches (klinai) and drinking wine. A hetaira, named "Syko" by the accompanying inscription, is playing the flute, while the host, named as Ekphantides, is chanting a song to honour Apollo. The words flood from his mouth in a composition resembling the speech bubbles of modern comics. Such scenes are relatively common. This is probably mostly because the vases were made to be used at comparable occasions, but perhaps also because painters like Euphronios belonged to the depicted circles of Athenian citizenry - or at least aspired to do so, as it is not clear to modern researchers what the social status of a vase painter was.

A signed psykter at the Hermitage (St. Petersburg) is also very well known. It depicts four hetairai feasting. One of them is labelled with the name Smikra, probably a humorous allusion to the young painter Smikros.

Apart from the feasting images, there are also some palaistra scenes, which permitted the artist to indulge his delight in movement, dynamics and musculature. One example is the only surviving piece by Euphronios in black-figure technique, fragments of which were found on the Athenian Acropolis. It was a Panathenaic amphora. Part of the head of Athena is recognisable. It is likely that the reverse, as was the norm for this vase shape, depicted an athletic competition in one of the sports that formed part of the Panathenaic Games.

Late phase

Euphronios's later works are partially beset by difficulties of attribution. In many cases, this is due to direct imitation or echoes of his own artistic style in the work of other painters working during his lifetime.

Well known is an unsigned volute krater, found in the 18th century near Arezzo. The main scene on the belly of the vase can easily be attributed to Euphronios. The krater shows a combat scene, with Heracles and Telamon at the center, fighting amazons. Telamon delivers the deathblow to a wounded amazon in Scythian clothing. Heracles is fighting the amazon Teisipyle, who is aiming an arrow at him. This late work is another example of Euphronios's search for new forms of expression. The scene is characterized by an impressive dynamic, which seems to have taken control of the artist, as he painted Telamon's leg in a very twisted position. The small frieze of komastes around the neck of the vase is problematic in terms of attribution. It may be by one of the master's assistants, perhaps by Smikros.

That particular krater appears to have been a central work, influencing and inspiring many others. For example, a neck amphora (Louvre G 107) shows a nearly identical scene, but in a style quite different from that of Euphronios. On it, Heracles is accompanied by a mysterious inscription: He appears to belong to Smikros. Perhaps it is a cooperation by both artists. A different situation applies to an amphora (Leningrad 610) that also shows a similar scene to the krater described above, but depicts Heracles as an archer. As the piece is similar to Euphronios's work not only in terms of motif but also of artistic style, Beazley hesitantly ascribed it to the master. The problem is that at this point, the style and skills of Smikros had grown very similar to those of his teacher, making it difficult to distinguish their works.

Euphronios's final works (Louvre G 33, Louvre G 43) are characterised by strong simplification. The motifs are less carefully composed than earlier works, probably because Euphronios concentrated on a different occupation from 500 BC onwards.

Euphronios as potter

Euphronios seems to have taken over a pottery workshop around 500 BC. It is not unusual in the history of Greek pottery and vase painting for artists to be active in both fields; several other painters from the Pioneer Group, such as Phintias and Euthymides are also known to have been potters. Nonetheless, the situation of Euphronios is unique insofar that he was initially active exclusively as a painter and later only as a potter.

In the following years, the Euphronios workshop mainly produced bowls. It is understandable that he should have made such a choice, as the potters (kerameis) probably were independent entrepreneurs, whereas the painters were employees. Thus, a potter had a higher chance to reach affluence. Some other hypotheses have been suggested, e.g. that Euphronios developed a true passion for the potter's craft. This is quite possible, as he turned out to be a highly skilled potter; in fact, his signature as potter survives on more vases than that as a painter. A further theory proposes that a deterioration of eyesight forced him to concentrate on a different activity. This view may be supported by the discovery of the base of a votive offering on the Acropolis. A fragmentary inscription contains the name Euphronios and the word hygieia (health). In modern scholarships, material considerations are, however, more generally accepted as relevant.

It is interesting that he chose bowls as the main product of his workshop. Heretofore, bowls had usually been painted by less skilled painters, and were probably in lower regards than other vases. His choice of painters indicates that he placed major emphasis on employing first class talents, such as Onesimos, Douris, the Antiphon Painter, the Triptolemos Painter and the Pistoxenos Painter, in his workshop.

Bibliography

- Euphronios, der Maler: eine Ausstellung in der Sonderausstellungshalle der Staatlichen Museen Preußischer Kulturbesitz Berlin-Dahlem, 20. März–26. Mai 1991. Fabbri, Milan 1991.

- Euphronios und seine Zeit: Kolloquium in Berlin 19./10. April 1991 anlässlich der Ausstellung Euphronios, der Maler. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-88609-129-5.

- Ingeborg Scheibler: Griechische Töpferkunst. 2nd ed. Beck, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-406-39307-1.

- Biography of Euphronios at the Getty Museum

References

- Vernon Silver, The Lost Chalice: The Epic Hunt for A Priceless Masterpiece (Harper Collins, 2009)