Little tunny

The little tunny (Euthynnus alletteratus), also known as the false albacore, little tuna, bonita, or erroneously as the blue bonito, is a species of tuna in the family Scombridae. It can be found in the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean and Black seas; in the western Atlantic, it ranges from Brazil to the New England states. The little tunny is a pelagic fish that can be found regularly in both offshore and inshore waters, and it is classified as a highly migratory species.[3][4] The little tunny is best identified by the "worm-like" markings on its back and the dark spots appearing between its pectoral and ventral fins.[5]

| Little tunny | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Scombriformes |

| Family: | Scombridae |

| Genus: | Euthynnus |

| Species: | E. alletteratus |

| Binomial name | |

| Euthynnus alletteratus (Rafinesque, 1810) | |

| |

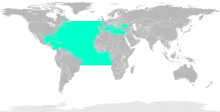

| Range of the little tunny | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

Commercially, the fish is used as bait for sharks and marlin due to its high oil content and hook retention. Because of its strong "fishy" taste and the considerable effort required to prepare it, the little tunny is considered by many to be a rough fish and is not commonly eaten.[6][7] However, it is sought after as a sport fish due to its line-stripping 64 km/h (40 mph) runs and hard fighting ability when hooked. By trolling with lures near reefs, it can be caught on hook and line.[6]

Taxonomy

Constantine Samuel Rafinesque identified the little tunny in 1810 and gave the fish its current name, Euthynnus alletteratus. Synonyms for used for the name include E. alleteratus alleteratus, E. alliteratus, E. thunina, and E. alletteratus aurolitoralis.[6] The little tunny is not part of the genus Thunnus like many tuna, but it is part of the tribe Thunnini.

Description

The little tunny is small in body size compared to other tuna species. It has a compact and stream-lined body built to facilitate bursts of speed, as well as endurance while swimming. Its torpedo-shaped, robust body is made for powerful swimming.[6] It has a large mouth with rigid jaws and a slightly protruding lower jaw, with a single row of small, inwardly curved, cone-shaped teeth on the palate.[8] Teeth are absent on the vomer, the small bone in the roof of the mouth,[6] and the tongue has two longitudinal ridges.[6]

The snout is shorter than the rest of the head. The little tunny has a dorsal fin with 10 to 15 tall, descending spines, as well as a much smaller second dorsal fin followed by eight finlets. At the base, the two dorsal fins are separated by a small interspace.[8] The anal fin has 11 to 15 slightly defined rays, and is followed by seven finlets. The pectoral fins are short and do not reach the end of the first dorsal fin and are joined to the pelvic fins by interpelvic processes.[6] There are 37-45 gill rakers, bony projections off the gills, on the first arch. There are no scales on the body of the little tunny except along the lateral line and on the corselet: a thick band of scales circling the body.[6][9]

The coloration of the little tunny is typically metallic blue or blue-green with dark, wavy stripes above the lateral line. These "worm-like" lines are within a well-marked border that never extends farther forward than the middle of the first dorsal fin.[8] The belly is bright white with three to seven dark, fingerprint-like spots around the pectoral and pelvic fins. The little tunny is commonly confused with the Atlantic bonito because of coloration, but the two fish differ in their color patterns and overall body size.

The little tunny's markings allow it to easily be distinguished from similar species. It is often confused with the skipjack tuna, the frigate tuna, the Atlantic bonito, and the bullet tuna. Close relatives also include the kawakawa and the black skipjack. The scattering of dark, fingerprint-like spots between the pectoral and pelvic fins cannot be found on any related Atlantic species. The first dorsal fin of the Atlantic bonito is also lower and sloping. Its lack of teeth on the vomer can set it apart from its close Pacific relatives, the kawakawa and the black skipjack. The dorsal fins of the bullet and frigate mackerel are set apart. Unlike the little tunny, the skipjack tuna lacks markings on the back and has broad, straight stripes on the underside.[10]

The little tunny reaches a maximum weight of 12 kg (26 lb) in the Mediterranean, and averages about 7 kg (15 lb) through its entire range. Its maximum fork length (distance from the tip of the snout to the fork of the tail) in the Mediterranean is about 100 cm (39 in) and in the Atlantic is about a 90 cm (35 in).[11] Average fork length for an adult fish throughout the entire range is about 85 cm (33 in).[12] Some fish may reach a length of 100 cm (39 in) or more, but most commonly they are around 64 cm (25 in). The largest little tunny on record is 120 cm (47 in) and 17 kg (37 lb).[13] Females reach sexual maturity at 27 to 37 cm (11–15 in) in fork length, while males mature at about 40 cm (16 in).[6]

Anatomy

The little tunny has some anatomical variations when compared to other species of Euthynnus. E. alletteratus lacks a swim bladder, like most other tuna, so it must constantly keep moving to stay afloat. The pectoral fins are crucial to the little tunny in maintaining its position in the water column. Its liver is very disproportionate, with the right lobe much longer than the left or middle lobes. The stomach of the little tunny is a long sac that stretches almost the entire length of its body. The intestinal tract is fairly short, coming from the left and right sides of the stomach, and extending without looping down the length of its body. The different sections are characterized by their diameter and color.[14] The ventral vertebral column of the little tunny has unique trelliswork, which is important to its family (Scombridae). Divided haemapophyses, or parts of the vertebrate forming a long canal, enclose the large ventral blood vessel.[15]

Feeding habits

In coastal waters along the North American eastern seaboard, little tunny are carnivorous, and primarily feed on small fish and invertebrates that occur in schools. Its diet consists mostly of fish; it particularly likes the Atlantic bigeye and largehead hairtail. Second to fish, the little tunny consumes crustaceans, and lastly cephalopods and gastropods make up a small part of its diet. Sardines, scad, and anchovies are common in the diet along with squid, stomatopods, and organisms from the family Diogenidae. The diet of the fish is also relative to its size. A smaller fish's diet typically consists of clupeiforms, and larvae, while the larger fish mostly eat Maurolicus muelleri. The typical diet is very similar to that of the king mackerel because the fish are of a similar size and live in the same area of the water column.[16] The little tunny is an opportunistic predator, feeding on crustaceans, clupeid fishes, squids, and tunicates. Its diet also responds to seasonal changes in food availability. There is conflicting evidence on if the little tunny is a nocturnal or diurnal feeder.[17] It is a specialist feeder, often feeding on herring and sardines in inshore waters near the surface of the water.[6] The little tunny commonly feeds in large schools because their primary food sources (small fish and the larval forms of crustaceans) are typically in schools, as well.

Distribution and habitat

The little tunny is found in the neritic waters of the temperate and tropical zones in the Atlantic ocean. It can also be found in the waters of the Mediterranean Sea and the Black Sea. In the eastern Atlantic, the little tunny has been found from Skagerrak to South Africa. Although found it this broad range of latitudes, it is rare north of the Iberian Peninsula or farther south than Brazil. On the Atlantic coast of the United States, they can be caught as far north as Cape Cod, Massachusetts, and as far south as the tip of Florida, as well as throughout the waters of the Gulf of Mexico.[18]

The little tunny's habitat tends to be near-shore waters, much closer to shore than most other tunas. They live in and around inlets, points, jetties, and sandbars. All of these places are where bait fish like sardine and menhaden, both favorites of the little tunny, form large schools, which are very helpful to the little tunny's feeding style. While the little tunny is abundant in offshore ocean waters, it is unusual to find it in brackish water of estuaries. The very young will enter estuaries in South Africa.[15] The little tunny prefers relatively warm water, from 24 to 30 °C. The little tunny migrates south in the winter and fall, and northward in the spring, through coastal waters. It is not as migratory as other tuna species.[10]

The little tunny is typically a schooling species.[15] It lives in schools based primarily on fish size rather than species, so other members of the family Scombridae, like the Atlantic bonito, may be present. These schools cover areas up to 3.2 kilometres long. Little tunny that have not yet reached adulthood form tight schools offshore. Larger schools are more common offshore whereas smaller groups may wander far inshore.

Reproduction

Little tunny spawn in water that is at least 25 °C (77 °F) in the months of April through November in the Atlantic Ocean. The spawning season of the little tunny in the Mediterranean is generally between May and September, but the most intensive spawning occurs between July and August. The major spawning areas are offshore, in waters that are 30 to 40 metres deep. The females are prolific fish, and can release 1.75 million eggs, in multiple clutches over a mating season.[6] The eggs are fertilized in the water column after the males release sperm. The eggs are buoyant, spherical, transparent, and pelagic. A droplet of oil within the egg adds to its buoyancy. The diameter of the eggs can be anywhere from 0.8 mm to 1.1 mm, and they are light amber. Larvae are released 24 hours after fertilization and are approximately 3 mm in size. Pigmentation in the eyes appear 48 hours after hatching. The teeth and fins develop at sizes of 3.7–14 mm. Once the larvae are 14 mm to 174 mm long, they take on the adult appearance; the body becomes more elongated.[19] Studies have found that it takes approximately 3 years for the little tunny's gonads to reach sexual maturity. The average size of a sexually mature individual is 38 cm (15 in) in fork length.[20]

Predators and parasites

Bony fish, Marlins, sea birds, sharks, and rays prey on the little tunny.[13] Other tunas, including conspecifics and yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares) are predators of the little tunny. Fish such as the dolphin fish (Coryphaena hippurus), wahoo (Acanthocybium solandri), Atlantic sailfish (Istiophorus albicans), swordfish (Xiphias gladius), and various sharks as well as other large marine carnivores all prey on the little tunny. Among those sharks is the whale shark, which feeds on the little tunny's recently spawned eggs. Seabirds prey on small little tunny.[6]

At least 3 species of sea lice are known parasites of the little tunny, all of the Caligus genus. These are found on the body surface and the wall of the branchial cavities. Another copepod, Pseudocycnoides appendiculatus, is a known parasite of the gill filaments. Other parasites include Digenea (flukes), Monogenea (gillworms), Cestoda (tapeworms), and isopods.[6]

Fishing

As with many inshore gamefish like bluefish and striped bass, schools of little tunny are usually indicated by flocks of birds diving in coastal waters. Fishermen targeting them often troll bait, cast lures, and float fish. When trolling for little tunny, fishermen often use small lures baited with either mullet or ballyhoo or lures dressed with colored feathers. When float fishing, popular baits are Spot, Bluefish, or Pinfish. Popular lures include deadly dicks, maria jigs, and other slender-profiled, brightly colored metal lures that can be cast far and retrieved quickly that imitate the small baitfish the little tunny are often feeding on. It is not uncommon for little tunny to be taken while shore fishing in the northern states along the East Coast of the United States, especially during late summer when the water near beaches is generally clear and easy for the fish to hunt in. Some anglers use little tunny for strip bait to catch other species, but most fish are released as the little tunny is not commonly thought of as a food fish. There is little regulation of the fishery, no size or bag limits, and no closed season. The flesh of the little tunny is coarse in texture, strong in flavor, and dark in color if compared to bluefin or yellowfin tuna.[21]

The little tunny is also native to the entire Mediterranean, especially around Sicily and the Ionian Sea. They love warm waters and cover long distances during the spring and summer mating season. The tuna is caught with longlines, containment nets and drift nets. The highest catch quota is achieved from April to September. Before overfishing, large schools migrated to the upper Adriatic, where they were observed from the karst. The last major catch in this regard was made in 1954 in the Trieste area by fishermen from Santa Croce and Barcola.[22]

References

- Collette, B.; Amorim, A.F.; Boustany, A.; et al. (2011). "Euthynnus alletteratus". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011: e.T170345A6759394. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-2.RLTS.T170345A6759394.en.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2018). "Euthynnus alletteratus" in FishBase. February 2018 version.

- Majkowski 2010.

- "Learn about the Little Tunny". guidesly.com. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- Schultz 2004, p. 259.

- Bester, Cathleen. "Little Tunny". Ichthyology Section. Florida Museum of Natural History. Archived from the original on 2013-06-03. Retrieved 25 October 2010.

- Steve Junker (16 September 2016). "Yummy or Not? The Myth of the Inedible False Albacore". capeandislands.org. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- "A Guide to the Tunas of the Western Atlantic". noreast.com. Retrieved 5 January 2011.

- Smith, Scott; Rohde, Fritz; Bissette, Jesse; Schobernd, Christina; Tracy, Bryn; Etchison, Luke; Hogue, Gabriela (2022). "Frigate Mackerel vs Bullet Mackerel". NCFishes.com. Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- "Little Tunny Fishing". GoFISHn. Archived from the original on 24 November 2010. Retrieved 4 January 2011.

- Macías et al. 2008, p. 2.

- Valeiras & Abad 2006, p. 233.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Euthynnus alletteratus" in FishBase. January 2012 version.

- Godsil 1954, p. 141.

- Romeo & Mansueti 1962.

- Manooch, Mason & Nelson 1985, p. 1207.

- Bahou 2007.

- Richardson 2001, p. 78.

- Kahraman & Akkatyli 2008, p. 551.

- Kahraman & Akkatyli 2008, p. 552.

- Romeo & Mansueti 1962, p. 257.

- Di Andrea Di Matteo (23 August 2014). "Santa Croce, 1954: ultima grande pescata di tonni". Il Piccolo (in Italian).

Cited texts

- Bahou, Laurent; Koné, Tidiani; N'Douba, Valentin; N'Guessan, Kouassi; Kouamélan, Essetchi; Gouli, Gooré (2006). "Food composition and feeding habits of little tunny (Euthynnus alletteratus) in continental shelf waters of Côte d'Ivoire (West Africa)". ICES Journal of Marine Science. 64 (5): 1044–1052. doi:10.1093/icesjms/fsm065.

- Falautano, M.; Castriota, L.; Finoia, M.G.; Andaloro, F. (2007). "Feeding ecology of little tunny Euthynnus alletteratus in the central Mediterranean Sea". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 87 (4): 999–1005. doi:10.1017/s0025315407055798. S2CID 84428736.

- Gilbert, Carter; Williams, James (1983). National Audubon Society Field Guide to Fishes. pp. 529–530.

- Godsil, Harry Carr (1954). "A descriptive study of certain tuna-like fishes". Fish Bulletin (97): 141–154. a54-9681. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- Kahraman, Alicli; Akkatyli, Oray (2008). "Reproductive biology of little tunny, Euthynnus alletteratus Rafinesque, from the northeastern Mediterranean Sea". Journal of Applied Ichthyology. 24 (5): 551–554. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0426.2008.01068.x.

- Liddell, H.G.; Scott, R.; Whiton, J.M. (1887). A lexicon abridged from Liddell and Scott's Greek-English lexicon (17th ed.). Ginn & Co. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- Macías D, Ortiz de Urbina JM, Gómez-Vives MJ, Godoy L, de la Serna J (2008). Size distribution of Atlantic little tuna (Euthynnus alletteratus) caught by south western Spanish Mediterranean traps and recreational trawl fisher (PDF) (Report). Fuengirola, Spain: Spanish Institute of Oceanography. pp. 1–7. Retrieved 4 January 2011.

- Majkowski, Jacek (15 November 2010). "FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Department". Rome. Retrieved 26 November 2010.

- Manooch, Charles S.; Mason, Diane L.; Nelson, Russell S. (1985). "Foods of little tunny Euthynnus alletteratus collected along the southeastern and Gulf coasts of the United States". Bulletin of the Japanese Society of Scientific Fisheries. 51 (8): 1207–1218. doi:10.2331/suisan.51.1207.

- Manooch, Charles (1984). Fisherman's Guide: Fishes of the Southeastern United States. pp. 200–201. ISBN 9780917134074. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- Richardson, Tom (2001). Inshore Salt Water Fishing: Learn from the Experts at Salt Water Magazine. Creative Publishing international, Inc. pp. 78–80. ISBN 978-0-86573-132-5.

- Romeo, J.; Mansueti, Alice (December 1962). "Little tuna, Euthynnus alletteratus, in northern Chesapeake Bay, Maryland, with an illustration of its skeleton". Chesapeake Science. 3 (4): 257–263. doi:10.2307/1350633. JSTOR 1350633.

- Schultz, Ken (2004). "Little Tunny". Ken Schultz's Field Guide to Saltwater Fish. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons, Inc. ISBN 978-0-471-44995-9. 597.177/dc22. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- Ursin, Michael (1977). A Guide to Fishes of the Temperate Atlantic Coast. pp. 198–199.

- Valeiras, J.; Abad, E. (4 September 2006). "Atlantic Black Skipjack" (PDF). ICCAT Manual: 233–238. Retrieved 8 September 2010.

- McClane's New Standard Fishing Encyclopedia and International Angling Guide. 1965. p. 553.

- "Sport Fishing - Little Tunny". TCPalm.com. E.W. Scripps. Archived from the original on 2013-05-12.

- Bahou, L. (July 2007). "Food composition and feeding habits of little tunny (Euthynnus alletteratus) in continental shelf waters of Côte d'Ivoire (West Africa)". ICES Journal of Marine Science. 64 (5): 1044–1052. doi:10.1093/icesjms/fsm065. Retrieved 6 October 2022.