Evans Bay Patent Slip

The Evans Bay Patent Slip is a heritage site of the former patent slip located in Evans Bay, in Wellington Harbour in the North Island of New Zealand. The first slipway on the site was commissioned in May 1863 to enable maintenance of the hulls of small vessels. The Wellington Provincial Council was keen to encourage shipping trade by improving facilities in Wellington Harbour and began planning later in 1863 for the construction of a larger patent slip. A concession was granted for the supply, construction and operation of a patent slip on the site. Equipment for the new slip was delivered in 1865 and 1866, but construction was delayed for several years because of a contractual dispute concerning the suitability of the design for the ground conditions. The original suppliers lost a court case and withdrew from the project. The Wellington Patent Slip Company was formed to take over the assets, and construction began in 1871. The Patent Slip was officially opened in March 1873.

| Evans Bay Patent Slip | |

|---|---|

NZGSS Matai, on Patent Slip at Evans Bay | |

| Nearest city | Wellington |

| Coordinates | 41°18′15.1″S 174°48′07.4″E |

| Built | 1863 |

| Demolished | 1980 |

| Current use | Public park |

| Owner | Wellington City Council |

| Designated | 25 November 1982 |

| Reference no. | 2895 |

A second slipway was constructed at the site in 1922. The original slip operated until 1969, and the second was closed on 31 July 1980. Most equipment has been removed from the site, and a residential development now occupies some of the original land. However, the site has been listed as a Category 2 historic place by Heritage New Zealand, and the area is classified as a heritage zone by the Wellington City Council.

The first slipway

In 1863, the New Zealand Steam Navigation Company decided to build a slip at Greta Point in Evans Bay to make it easier to repair and clean ships' hulls. A contract was let to shipwright Edward Thirkell, and by May 1863 the slip was in operation.[1] This first slip was 300 feet (91 m) long, with the upper part being bolted together so that it could be removed from under any ship if necessary. The slip itself consisted of two wooden "slideways" for the keel and the bilge, and the low end sat in eight feet (2.4 m) of water at low tide. Two manually-operated winches pulled ships up the runners.[2] Edward Thirkell managed this slip and its successor until his death in 1882.[3] The New Zealand Steam Navigation Company went into liquidation in 1871,[4] and management of the slip passed to the newly formed Patent Slip Company.[5][6] The wooden slip was in use at least until 1873, when the new slip was built slightly south of it.[7]

The Patent Slip

The immediate success of the first slipway led the Wellington Provincial Council to investigate building a bigger slip that could handle larger ships.[8] In December 1863, the New Zealand Government passed empowering legislation authorising the Superintendent of Wellington to compulsorily acquire an area of land up to 20 acres (8.1 ha) at Evans Bay for the construction of a larger Patent Slip.[9] The Wellington Provincial Council was keen to have a slip capable of taking large vessels to increase the attractiveness of Wellington Harbour for the shipping trade. However, the Provincial Council was unable to fund the construction, and decided to grant a concession for a slipway to be built and operated. The concession was granted to Kennard Bros., of London.[10]

Kennards manufactured and delivered hundreds of tons of machinery to Wellington in 1866.[11] However there was a contractual dispute about extra work required due to the nature of the site at Evans Bay, so the equipment sat there on the beach for five years while the dispute was discussed.[12] In 1871 Wellington businessmen formed the Wellington Patent Slip Company and bought the equipment from Kennards.[12][13] Construction began in 1871 and was completed in May 1873.[11][10][14]

.jpg.webp)

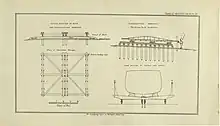

The Evans Bay Patent Slip, the first in New Zealand, was a major engineering achievement. A 200-ton, 180-foot-long (55 m) cradle moved on wheels along parallel rails. Two chains were used for hauling vessels out of the water and lowering them back down. The chains ran over a cogwheel winch powered by two steam engines. The main 'hauling up' chain was 1,700 feet (520 m) long and weighed 62 tons. Each link was 18 inches (46 cm) long and made of iron three inches (7.6 cm) thick. One end of the chain was attached to the cradle and the other dropped into a 35-foot-deep (11 m) well beneath the winding gear. The smaller 'lowering out' chain was a loop with links 1+1⁄4 inches (3.2 cm) thick. This was used for lowering ships down the slip and for bringing up the empty cradle.[15]

Construction on land above the high tide line was straightforward, but work under the water was much more complicated. Workers in a diving bell excavated the sea floor, shifting rock into a shallow iron box which they slid under the edge of the diving bell to be hauled to the surface and removed. The men worked in shifts of four to six hours. After this stage, a diver worked to position piles and join pieces together. Concrete was mixed in a boat on the surface and sent underwater down a tube with a canvas hose at the end so that the diver could direct the concrete to where it was needed. The workers underwater could only work in good weather conditions: in a southerly the current was strong enough to lift a diver off the sea floor.[15][16] This was the first large-scale underwater construction in New Zealand.[17] A 500-foot (150 m) jetty was also erected to improve communication with ships. Along with housing for the winches and boilers required to operate the slipways, there were some houses, a store, an inspector's office, a carpenter's shop, a messroom, and a blacksmith's shop.[17]

On 2 May 1873, the 316-ton barque Cyprus was the first ship to use the slipway.[11] If necessary, two ships could use the slip at the same time. The first ship would be raised up and then chocks put under it so that the cradle could be released and sent down to pull up a second ship.[18] A small vessel could be raised up the slip in about 20 minutes, and a larger ship could be raised at a rate of 15 or 16 feet per minute (4.6 or 4.9 m/min).[15] The press reported that the slip could handle ships weighing up to 2,000 tons and was "the finest and largest in the Australian colonies".[19] By the late 1890s there were calls for a dry dock in Wellington, amid claims that the Patent Slip could not cope with the increased size and number of ships visiting Wellington.[20]

Early in 1908, the Union Steam Ship Company acquired 90% of the shares in the Wellington Patent Slip Company.[21] In July 1908, after months of meetings and negotiations with the Patent Slip Company and the Union Steam Ship Company, Wellington Harbour Board acquired the property where the slip was located.[22][23] Under the agreement, the Patent Slip Company would continue to manage the slip for the next 25 years and build a second slip if required. This was constructed in 1922.[10] Also under the agreement, an area of land not required for slip operations was set aside for the use the Union Steam Ship Company for a 25-year period. After 25 years, the Harbour Board would pay the Patent Slip Company £30,000 and acquire the patent slip operation. The Harbour Board would also pay the USSCo for any improvements it made to the land it was using.[23] The agreement expired in 1933 and after consultation and negotiation it was decided in 1935 that the Harbour Board would continue to lease Patent Slip Company operations and the land used by the USSCo to those two companies on periodic leases.[24][25] In 1961, the Union Steamship Company chose not to renew its lease, so the Harbour Board took over management of both slips until 1969. At that time slipway No. 1 was taken out of service and slipway No. 2 was upgraded. The slipway closed on 31 July 1980.[10] The site was demolished and various equipment scrapped, sold or given to museums, and land was filled in for a new housing subdivision.[10]

The site was listed as a Category 2 historic place in 1982.[17] Wellington City Council had the site rezoned as a heritage area in 2003, and the area is now known as Cog Park.[11]

Incidents at the slip

Over the many years of operation there were several significant incidents at the Patent Slip.

| Year | Vessel name | Type | Tonnage | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1878 | Large flywheel shattered, causing major damage to engine room and machinery | [26] | |||

| 1909 | NZGSS Hinemoa | Steamer | 542 | Haul-out failure – fracture of 16-foot-diameter (4.9 m) main geared haul wheel | [27] |

| 1914 | Karori | Steamer | 1863 | Fracture of haul chain – leading to uncontrolled re-entry to the water | [28] |

| 1925 | Muritai | Harbour ferry | Vessel tailshaft dislodged coming off cradle leading to water ingress. Vessel was beached nearby. | [29] | |

| 1926 | Kartigi | Steamer | 2347 | Fracture of haul chain | [30] |

| 1935 | Natone | Tug | 75 | Tug heeled over and sustained damage during haul-out. Floating crane Hikitia used for recovery. | [31] |

| 1947 | Tapuhi | Tug | 232 | Support cradle collapsed beneath tug | [32] |

Gallery

Man working at Patent Slip, c. 1920s

Man working at Patent Slip, c. 1920s Patent Slip, c. 1880

Patent Slip, c. 1880 Barque Pleione in the Patent Slip

Barque Pleione in the Patent Slip.jpg.webp) View north at Patent Slip, c. 1880

View north at Patent Slip, c. 1880 Hauling machinery at the Patent Slip

Hauling machinery at the Patent Slip

References

- "New Zealand Steam Navigation Company". Wellington Independent. 2 April 1863. Archived from the original on 3 October 2022. Retrieved 3 October 2022 – via Papers Past.

- "The Patent Slip". Wellington Independent. 19 May 1863. Archived from the original on 3 October 2022. Retrieved 3 October 2022 – via Papers Past.

- "[untitled]". Evening Post. 7 July 1882. Archived from the original on 21 October 2022. Retrieved 21 October 2022 – via Papers Past.

- "NZSN Company's meeting". Wellington Independent. 8 March 1871. Archived from the original on 4 October 2022. Retrieved 4 October 2022 – via Papers Past.

- "The patent slip". Evening Post. 15 March 1873. Archived from the original on 4 October 2022. Retrieved 5 October 2022 – via Papers Past.

- "[untitled]". Evening Post. 12 May 1871. Archived from the original on 4 October 2022. Retrieved 4 October 2022 – via Papers Past.

- "[untitled]". Wellington Independent. 17 January 1873. Archived from the original on 4 October 2022. Retrieved 4 October 2022 – via Papers Past.

- "New Zealand Provinces: Wellington". Nelson Examiner and New Zealand Chronicle. 20 June 1863. Archived from the original on 3 October 2022. Retrieved 3 October 2022 – via Papers Past.

- "The Wellington Patent Slip Act 1863". New Zealand Government. 14 December 1863 – via University of Auckland – Early New Zealand Statutes.

- "Evans Bay Patent Slip Area". www.wellingtoncityheritage.org.nz. Archived from the original on 7 October 2022. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

- McLean, Gavin (2013). "Evans Bay Patent Slip". nzhistory.govt.nz. Archived from the original on 6 October 2022. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

- "Patent Slip Meeting". Wellington Independent. 16 March 1871. Retrieved 5 February 2023 – via Papers Past.

- "Wellington Patent Slip Company". New Zealand Mail. 22 April 1871. Retrieved 5 February 2023 – via Papers Past.

- "Patent Slip Dinner". Wellington Independent. 7 May 1873. Archived from the original on 5 October 2022. Retrieved 5 October 2022 – via Papers Past.

- "Description of the Patent Slip at Evans Bay, Wellington, and of the mode of erecting or constructing the same". Transactions and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 6: 14–25. 1873. Archived from the original on 6 October 2022. Retrieved 6 October 2022 – via Papers Past.

- "[untitled]". Wellington Independent. 27 September 1872. Archived from the original on 7 October 2022. Retrieved 7 October 2022 – via Papers Past.

- "Evans Bay Patent Slip (Former)". Heritage New Zealand. Archived from the original on 16 March 2023. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

- "[untitled]". Wellington Independent. 30 August 1873. Archived from the original on 7 October 2022. Retrieved 7 October 2022 – via Papers Past.

- "[untitled]". New Zealand Times. 16 October 1876. Retrieved 5 February 2023 – via Papers Past.

- "The Proposed Dock". Evening Post. 26 March 1897. Retrieved 5 February 2023 – via Papers Past.

- "The Patent Slip". New Zealand Times. 15 January 1908 – via Papers Past.

- "The Patent Slip: Prospect of settlement". Evening Post. 8 July 1908 – via Papers Past.

- "The Patent Slip: Union Company and Board". New Zealand Times. 24 July 1908 – via Papers Past.

- "The Patent Slip changing hands?". Evening Post. 30 August 1933 – via Papers Past.

- "Board takes over". Evening Post. 25 July 1935 – via Papers Past.

- "Frightful accident at the Patent Slip". Evening Post. 8 January 1878. Archived from the original on 21 October 2022. Retrieved 21 October 2022 – via Papers Past.

- "Wellington Patent Slip – Serious mishap – Breaking of large wheel". Wairarapa Daily Times. 2 April 1909. Archived from the original on 5 October 2022. Retrieved 5 October 2022 – via Papers Past.

- "Came down the slip – Mishap to Karori – No damage done". Star (Christchurch). 25 September 1914. Archived from the original on 5 October 2022. Retrieved 5 October 2022 – via Papers Past.

- "Mishap to ferry steamer". Manawatu Standard. 17 July 1925. Archived from the original on 5 October 2022. Retrieved 5 October 2022 – via Papers Past.

- "Mishap at slips – Hauling chain breaks – Attempts to refloat vessel". Wanganui Chronicle. 11 August 1926. Archived from the original on 5 October 2022. Retrieved 5 October 2022 – via Papers Past.

- "Mishap to Wellington tug". Otago Daily Times. 26 August 1935. Archived from the original on 5 October 2022. Retrieved 5 October 2022 – via Papers Past.

- "Mishap at Patent Slip – Tug heels over on cradle". The Press. 4 November 1947. Archived from the original on 5 October 2022. Retrieved 5 October 2022 – via Papers Past.

External links

![]() Media related to Evans Bay Patent Slip at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Evans Bay Patent Slip at Wikimedia Commons