Execration texts

Execration texts, also referred to as proscription lists,[1] are ancient Egyptian hieratic texts, listing enemies of the pharaoh, most often enemies of the Egyptian state or troublesome foreign neighbors.[2] The texts were most often written upon statuettes of bound foreigners, bowls, or blocks of clay or stone, which were subsequently destroyed. The ceremonial process of breaking the names and burying them was intended to be a sort of sympathetic magic that would affect the persons or entities named in the texts. The fragments were usually placed near tombs or ritual sites. This practice was most common during times of conflict with the Asiatic neighbors of Egypt.[3]

Historical periods of execration texts

Execration texts are attested from the late Old Kingdom (c. 2686–2160 BCE) up into the New Kingdom (c. 1550–1069).

The earliest physical execration texts date to the 6th dynasty (24th–22nd century BCE) during Egypt's Old Kingdom. They are statuettes made from unbaked clay and fashioned into the shape of bound foreigners with name labels inscribed on their chests, sometimes in red ink.[4][5] Over 400 of these statuettes were excavated from the cemetery at Giza, while a few others have been unearthed at the settlements of Elephantine and Balat.[4]

In the Middle Kingdom (c. 2055–1650), Egyptians continued to use statuettes as execration texts. For example, a group of both large and small figurines dating to the end of the 12th dynasty was excavated at the necropolis of Saqqara.[4] Middle Kingdom Egyptians also began to use pottery vessels for execration texts, which is evidenced by an excavation of over 175 vessels outside the Egyptian fortress at Mirgissa in Lower Nubia. These vessels, dating to the middle of the 12th dynasty, were inscribed with lengthy execration texts and appear to have been deliberately broken, likely as part of the execration ritual.[4]

Only a few examples of execration texts dating to the Second Intermediate Period (c. 1700–1550) and New Kingdom (c. 1550–1069) have been found.[6]

Periods reflected in the texts

It has been noted that the later execration texts created during the Middle Kingdom, at least partially repeat, with some updates, formulas from the older, Old Kingdom texts.[7] Ben-Tor therefore argues that Middle Kingdom texts don't reflect, either in part or entirely, the historical reality of their time, but that of the Old Kingdom or, archaeologically speaking, of the Early Bronze Age (EB) rather than the Middle Bronze Age (MB).[7] He points out that the identified sites were all occupied during the EB, most of them being fortified.[7]

Sites where execration texts were found

There have been over 1,000 execration deposits found, with sites at Semna, Uronarti, Mirgissa, Elephantine, Thebes, Balat, Abydos, Helwan, Saqqara, and Giza.[8] Because the execration jars, figurines, vases, and statues were almost destroyed during the rituals, archaeologists have to put all the pieces they find from execration pits back together to learn about the rituals. Four deposits have been uncovered at Giza, which contained figurines packed into pottery jars.[9]

At the Middle Kingdom fortress of Mirgissa, execration remains included 200 broken inscribed red vases, over 400 broken uninscribed red vases, nearly 350 mud figurines, four limestone figures, small traces of beeswax dyed red-probably the remnants of melted figurines, and one human-whose head was ritually severed.[10][11] Other evidence of human sacrifice and execration victims, as well as animal sacrifice was found at Avaris, probably from the 18th dynasty. Two execration pits were found: one containing skulls and fingers while the other had two full male skeletons.

Georges Posener published his findings from Saqqara in 1940, which later became known as the Brussels texts. Figurines there name over 60 enemy cities, people, and tribes.[12]

The execration ritual

The execration ritual was the process by which one could thwart or eradicate one's enemies. Usually the ritual object(s) would be bound (usually a small figurine, but sometimes human sacrifice was practiced), then the object was smashed, stomped on, stabbed, cut, speared, spat on, locked in a box, burned, saturated in urine, and finally buried. But not every execration included all of the previous components. A full rite could use any of these actions numerous times with numerous figures. One recorded rite gave instructions to "spit on him four times ... trample on him with the left foot ... smite him with a spear ... slaughter him with a knife ... place him on the fire ... spit on him in the fire many times"[8][13]

Places mentioned

The presence of foreign names of cities and tribes has long been a source for researchers to learn more about the dates and influence of these sites. The first two groups of execration texts published, the Berlin and Brussels texts, contain numerous mentions of Canaanite and Phoenician cities. The Berlin and Brussels texts date approximately from the end of the 20th century BCE to midway through the 18th century BCE. From an archaeological standpoint, these execration texts range from MB I to MB IIB. Archaeological remains from this period have not been found in all of the sites mentioned on Egyptian execration texts.[14]

Places mentioned in execration texts for which there is substantial archaeological remains from MB IIA:[15]

Places mentioned in execration texts with little or no archaeological remains from MB IIA:[15]

The site Beit She'an may also have been mentioned in these sets of execration texts, but this site has not been identified with certainty. Byblos was mentioned as the name of a tribe in execration texts, but not as a site.[16]

Most scholars claim that the Šu-tu mentioned in execration texts and other Egyptian texts may refer to the land and people of Moab due to the text in Numbers 24:17 which refers to the Moabites as the "sons of Sheth". However, it is also possible that the term Šu-tu may refer to all people living in an area ranging from Wadi al-Hassa to Nahr ez-Zerqa, instead of referring exclusively to Moab.[17]

The Kingdom of Kush in Nubia is also mentioned in execration texts.

Research

The execration texts are an important resource for researchers in the field of ancient Near Eastern history of the 20th–18th centuries BCE[18] and Bible studies. The first group of execration texts were published by Kurt Sethe in 1926, known as the Berlin texts. Georges Posener published a second group of texts in 1957, known as the Brussels texts.[19][12]

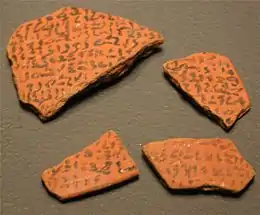

The first collection are inscribed on pottery sherds, and contain the names of approximately 20 places in Canaan and Phoenicia, and over 30 rulers of the period. These texts contain what is possibly the first known mention of Jerusalem,[20] from the beginning of the 2nd millennium BCE, the end of the 11th Dynasty to the 12th Dynasty.

The second group of texts are inscribed on figurines of bound prisoners discovered in Saqqara. This group contains the names of 64 places, usually listing one or two rulers. Seven known Asian countries are listed.[21] This group has been dated to the end of the 12th Dynasty.

An additional group of texts, the Mirgissa texts, was published by Yvan Koenig in 1990.

The execration texts are mostly inscribed on (un)baked clay materials and written in black carbon or red iron containing pigments. An obstacle to still being able to read them after thousands of years is that these texts have faded over time. This has partly been overcome by applying multi-spectral imaging techniques to enhance their readability.[22]

Historical interpretation

The interpretation of historians as to the meaning of execration texts has been well established thanks to documents that detail the ritual creation of the texts and the manner in which they were to be destroyed[23] in order to invoke a form of magic to protect Egypt and the pharaoh, in earlier cases, but especially in the Ptolemaic period they began to be utilized by more and more Egyptians for their own personal use.[24]

Because many of the early execration texts are found on pottery, some historians believe that the ritual smashing of execration figures originated from the smashing of clay vessels used in funerary preparations so as to prevent their use for other purposes and to relinquish any magical power that may have resided in the vessel after having been used for funerary washings.[25]

Beyond Egyptian borders

Execration texts deal with kings and cities who the Egyptians felt threatened by; some of whom lived in the Canaanite and Syrian lands. Execration texts including the Berlin, Brussels, and Migrissa groups contain curses targeting over 100 Syro-Palestinian kings and villages.[26]

Nubian kings such as Segersenti were mentioned in execration texts, as well as over 200 other Nubian kings.[27]

Biblical connections to execration texts: Egyptian sources are important when wanting to understand the history of Canaan. Their relationship with Egyptian pharaohs is brought to life by some execration texts.[28] Some execration texts refer to the people living on both sides of the Jordan River as su-tu. Scholars make a connection with the su-tu and the "sons of Sheth" or "bene-set", referred to in the book of Numbers 24:17 of the Bible:

"I shall see him, but not now: I shall behold him, but not nigh: there shall come a Star out of Jacob, and a Sceptre shall rise out of Israel, and shall smite the corners of Moab, and destroy all the children of Sheth." (Hebrew: בני שת bənê-Šêṯ)

It is widely accepted that the "sons of Sheth" are those who dwelt in Moab, or the Moabites, on the borders of the Hebrews' lands.[29]

Dr. A. Bentzen in the 1950s advanced his thesis that the first and second chapters of the book of Amos in the Old Testament "is modelled on cultic patterns, resembling the ritual behind the Egyptian Execration Texts." Many have taken this theory and interpreted it wrongly by saying there is evidence that Amos' speech is influenced by Egyptian execration texts. Bentzen is simply stating that the influences for Amos' speech resemble (are not influenced by) Egyptian execration texts. They are similar, but there is no connection. Other books of the Bible share this same similarity; Daniel 11:41; Isaiah 11:14; Jeremiah 48–49; Zephaniah 2:8–9; Ezekiel 25:1–14 and Nehemiah 13:1–2:23.[30]

See also

References

- Edwards, Gadd, and Hammond (1971), p. 494

- Pinch, Geraldine (1995). Magic in ancient Egypt. University of Texas Press. p. 92f. ISBN 978-0-292-76559-7.

- Edwards, Gadd, and Hammond (1971), p. 508.

- Seidlmayer, Stephan J. (2001). "Execration Texts". The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press.

- See Seidlmayer (2001) and Theis, Christoffer (2014). "Magie und Raum. Der magische Schutz ausgewählter Räume im Alten Ägypten nebst einem Vergleich zu angrenzenden Kulturbereichen". Orientalische Religionen in der Antike 13, Tübingen, pp. 65–87 for a collection of the material.

- Van De Mieroop, Marc (2011). A History of Ancient Egypt. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-4051-6071-1.

- Ben-Tor (2006), p. 81.

- Muhlestein, Kerry. 2008, Execration Ritual. In Willeke Wendrich, Jacco Dieleman (eds.). UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, Los Angeles.

- Abu Bakr, Abdel Moneim, and Jürgen Osing, "Ächtungstexte aus dem Alten Reich", MDAIK 29, 1973, 97–133; Osing, "Ächtungstexte aus dem Alten Reich (II)", pp. 133–85; Hermann Junder, Giza VIII, Vienna: Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1947, pp. 30–38; and Stephan J. Seidlmayer, "Gräberfelder aus dem Übergang vom Altern zum Mittleren Reich". Studien zur archäologie der Ersten Zwischenzeit, Heidelberg: Heidelberger Orientverlag, 1990, pp. 488–89.

- Ritner, Robert. 1993. The mechanics of ancient Egyptian magical practice. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization 54. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 153–154

- Vila, Un rituel, p. 631, fig. 15: and Ritner, The Mechanics of Ancient Egyptian, p. 163

- Ben-Tor (2006).

- Schott, Siegfried. 1929 Urkunden mythologischen Inhalts. Urkunden des aegyptischen Altertums 6, ed. Georg Steindorff. Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs.

- Ben-Tor (2006), pp. 63–87; see the last references and maps by Christoffer Theis, "Magie und Raum. Der magische Schutz ausgewählter Räume im Alten Ägypten nebst einem Vergleich zu angrenzenden Kulturbereichen" (Orientalische Religionen in der Antike 13), Tübingen 2014, pp. 82–85.

- Ben-Tor (2006), p. 67.

- Ben-Tor (2006), p. 68.

- Worschech (1997), pp. 229–230

- Albright, W.F. (1969). Studies in the history of culture: the disciplines of the humanities. Ayer Publishing. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-8369-1170-1.

- Wright, G. E. (1961). The Bible and the ancient Near East: Essays in Honor of William Foxwell Albright. Doubleday. p. 304. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- David Noel Freedman; Allen C. Myers; Astrid B. Beck (2000). Eerdmans dictionary of the Bible. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 694–695. ISBN 978-0-8028-2400-4.

- Aharoni, Yohanan (1979). The land of the Bible: a historical geography. Westminster John Knox Press. pp. 144–147. ISBN 978-0-664-24266-4.

- Van der Perre, Athena; Braekmans, Dennis; Boschloos, Vanessa; Ossieur, France; Hameeuw, Hendrik; Delvaux, Luc (2018). "The Egyptian Execration Figurines of the Royal Museums of Art and History, Brussels: Conservation, Pigments and Digitisation". Bulletin des Musées royaux d’Art et d’Histoire. 87/88: 5–29.

- Françoise Dunand, Christiane Zivie-Coche, Gods and Men in Egypt: 3000 BCE To 395 CE, Cornell University Press, 2005, pg. 126

- Paul Allan Mirecki, Marvin W. Meyer, Magic and Ritual in the Ancient World, Brill 2002, Part 4, p. 440

- Jacobus Van Dijk, The New Kingdom Necropolis of Memphis, Groningen, 1993, p. 185f

- (Egyptian Relations with Palestine in the Middle Kingdom James M. Weinstein Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, No. 217 (Feb. 1975), pp. 1–16)

- (Three Rulers in Nubia and the Early Middle Kingdom in Egypt Bruce Williams Journal of Near Eastern Studies, Vol. 72, No. 1 (April 2013), pp. 1–10)

- (Hebrew Books and Papers Israel Exploration Journal, Vol. 10, No. 3 (1960), pp. 184–189)

- (Egypt and Moab Udo Worschech The Biblical Archaeologist, Vol. 60, No. 4, The Archaeology of Moab (Dec., 1997), pp. 229–236)

- (The Pattern of the 'Execration Texts' in the Prophetic Literature M. WEISS Israel Exploration Journal, Vol. 19, No. 3 (1969), pp. 150–157)

Bibliography

- I.E.S. Edwards; C.J. Gadd; N.G.L. Hammond (1971). The Cambridge Ancient History: Early History of the Middle East. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-07791-0. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- Nicolás Grimal (1994). A history of ancient Egypt. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-19396-8.

- Ben-Tor, Amnon (2006), Yaira Amit; Nadav Naʼaman (eds.), "Do the Execration Texts reflect an accurate picture of the contemporary settlement map of Palestine?", Essays on ancient Israel in its Near Eastern context: a tribute to Nadav Naʼaman, EISENBRAUNS, pp. 63–87, ISBN 978-1-57506-128-3 Re-accessed 20 July 2022.

- Georges Posener: Princes et Pays d'Asie et de Nubie. Textes hiératiques sur des figurines d'envoûtement du Moyen Empire. Brüssel 1940 (Jüngere Texte der 12. Dynastie).

- Kurt Sethe: Die Ächtung feindlicher Fürsten, Völker und Dinge auf altägyptischen Tongefäßscherben des Mittleren Reiches. (=: Abhandlungen der Preußischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. 1926, philos-histor. Klasse Nr. 5) Berlin 1926 (Ältere Ächtungstexte aus der 12. Dynastie).

- Christoffer Theis, Magie und Raum. Der magische Schutz ausgewählter Räume im Alten Ägypten nebst einem Vergleich zu angrenzenden Kulturbereichen (Orientalische Religionen in der Antike 13), Tübingen 2014, pp. 65–87.

- Christoffer Theis: Ächtungstexte. In: Michaela Bauks, Klaus Koenen, Stefan Alkier (Hrsg.): Das wissenschaftliche Bibellexikon im Internet (WiBiLex), Stuttgart 2006 ff.

- Thomas L. Thompson (2002). The historicity of the patriarchal narratives: the quest for the historical Abraham. Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 98–117. ISBN 978-1-56338-389-2.

- Worschech, Udo (December 1997). "Egypt and Moab". The Biblical Archaeologist. 60 (The Archaeology of Moab): 229–236. doi:10.2307/3210625. JSTOR 3210625. S2CID 164026781.