Intercalation (chemistry)

In chemistry, intercalation is the reversible inclusion or insertion of a molecule (or ion) into layered materials with layered structures. Examples are found in graphite and transition metal dichalcogenides.[1][2]

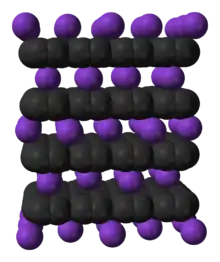

Model of intercalation of potassium into graphite

Model of intercalation of potassium into graphite

Examples

Graphite

One famous intercalation host is graphite, which intercalates potassium as a guest.[3] Intercalation expands the van der Waals gap between sheets, which requires energy. Usually this energy is supplied by charge transfer between the guest and the host solid, i.e., redox. Two potassium graphite compounds are KC8 and KC24. Carbon fluorides (e.g., (CF)x and (C4F)) are prepared by reaction of fluorine with graphitic carbon. The color is greyish, white, or yellow. The bond between the carbon and fluorine atoms is covalent, thus fluorine is not intercalated. Such materials have been considered as a cathode in various lithium batteries.

Treating graphite with strong acids in the presence of oxidizing agents causes the graphite to oxidise. Graphite bisulfate, [C24]+[HSO4]−, is prepared by this approach using sulfuric acid and a little nitric acid or chromic acid. The analogous graphite perchlorate can be made similarly by reaction with perchloric acid.

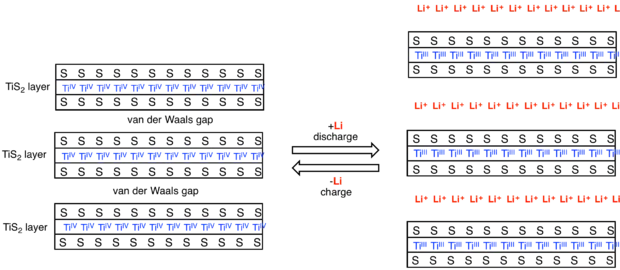

Metal dichalcogenides

Another well-known family of intercalation hosts are the layered metal dichalcogenides such as titanium disulfide.[4] In characteristic manner, intercalation is analyzed by X-ray diffraction, since the spacing between sheets increases, and by electrical conductivity, since charge transfer alters the number of charge carriers.

A structurally related species is iron oxychloride.

Exfoliation

An extreme case of intercalation is the complete separation of the layers of the material. This process is called exfoliation. Typically aggressive conditions are required involving highly polar solvents and aggressive reagents.[5]

Related materials

In biochemistry, intercalation is the insertion of molecules between the bases of DNA. This process is used as a method for analyzing DNA and it is also the basis of certain kinds of poisoning.

Clathrates are chemical substances consisting of a lattice that traps or contains molecules. Usually, clathrate compounds are polymeric and completely envelop the guest molecule. Inclusion compounds are often molecules, whereas clathrates are typically polymeric. Intercalation compounds are not 3-dimensional, unlike clathrate compounds.[6] According to IUPAC, clathrates are "Inclusion compounds in which the guest molecule is in a cage formed by the host molecule or by a lattice of host molecules."[7]

See also

- Clathrate compound: where a molecule is included into a lattice

- Graphite intercalation compound

- Intercalation (biochemistry)

- Stacking (chemistry)

- Hydrogen embrittlement

Notes

- Stanley M Whittingham (2 December 2012). INTERCALATION CHEMISTRY. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-323-14040-9. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- W. Müller-Warmuth; R. Schöllhorn (6 December 2012). Progress in Intercalation Research. Physics and Chemistry of Materials with Low-Dimensional Structures 17. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-94-011-0890-4. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- Wiberg, E.; Holleman, A.F.; Wiberg, N.; Eagleson, M.; Brewer, W.; Aylett, B.J. (2001). Inorganic Chemistry. Academic Press. p. 794. ISBN 978-0-12-352651-9. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- Kikkawa, S.; Kanamaru, F.; Koizumi, M. (1983). "Layered Intercalation Compounds". Inorganic Syntheses. Vol. 22. p. 86. doi:10.1002/9780470132531.ch17. ISBN 0-471-88887-7.

- Nicolosi, V.; et al. (2013). "Liquid Exfoliation of Layered Materials". Science. 340 (6139). doi:10.1126/science.1226419. hdl:2262/69769.

- Atwood, J. L. (2012). "Inclusion Compounds". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a14_119.

- IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "clathrates". doi:10.1351/goldbook.C01097