Vayakhel

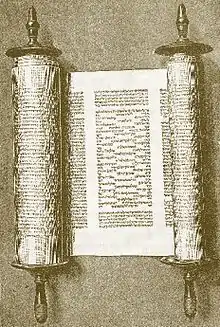

Vayakhel, Wayyaqhel, VaYakhel, Va-Yakhel, Vayak'hel, Vayak'heil, or Vayaqhel (וַיַּקְהֵל—Hebrew for "and he assembled," the first word in the parashah) is the 22nd weekly Torah portion (פָּרָשָׁה, parashah) in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the 10th in the Book of Exodus. The parashah tells of the making of the Tabernacle and its sacred vessels. It constitutes Exodus 35:1–38:20. The parashah is made up of 6,181 Hebrew letters, 1,558 Hebrew words, 122 verses, and 211 lines in a Torah scroll (סֵפֶר תּוֹרָה, Sefer Torah).[1]

Jews read it the 22nd Sabbath after Simchat Torah, generally in March or rarely in late February. The lunisolar Hebrew calendar contains up to 55 weeks, the exact number varying between 50 in common years and 54 or 55 in leap years. In leap years (for example, 2024 and 2027), Parashat Vayakhel is read separately. In common years (for example, 2023 and 2026), Parashat Vayakhel is usually combined with the next parashah, Pekudei, to help achieve the number of weekly readings needed (although in some non-leap years, such as 2025, they are not combined).[2]

Readings

In traditional Sabbath Torah reading, the parashah is divided into seven readings, or עליות, aliyot.[3]

First reading—Exodus 35:1–20

In the first reading (עליה, aliyah), Moses convoked the Israelites to build the Tabernacle. Moses started by reminding them of God's commandment to keep the Sabbath of complete rest.[4] Then Moses told them to collect gifts of materials from those whose heart so moved them—gifts of gold, silver, copper, colored yarns, fine linen, goats hair, tanned ram skins, acacia wood, olive oil, spices, lapis lazuli, and other stones.[5] Moses invited all who were skilled to make the Tabernacle, its furnishings, and the priests' vestments.[6]

Second reading—Exodus 35:21–29

In the second reading (עליה, aliyah), the Israelites brought the gifts that Moses requested.[7]

Third reading—Exodus 35:30–36:7

In the third reading (עליה, aliyah), Moses announced that God had singled out Bezalel and Oholiab to endow them with the skills needed to construct the Tabernacle.[8] And Moses called on them and all skilled persons to undertake the task.[9] The Israelites brought more than was needed, so Moses proclaimed an end to the collection.[10]

.jpg.webp)

Fourth reading—Exodus 36:8–19

In the fourth reading (עליה, aliyah), the skilled workers fashioned the Tabernacle's curtains, loop, clasps, and coverings.[11]

.jpg.webp)

Fifth reading—Exodus 36:20–37:16

In the long fifth reading (עליה, aliyah), they made the Tabernacle's standing, gold clad, polished boards each with 2 tenons, and their 2 silver sockets, bars of acacia-wood overlaid with gold, rings of gold, veil of the covering, 4 pillars of acacia-wood overlaid with gold, screen for the door held by 5 gold clad pillars, and sockets of brass.[12] Bezalel made the ark, cover, and 7 golden oil lamps pushed over against the golden lampstand which partially covers the table.[13]

Sixth reading—Exodus 37:17–29

In the sixth reading (עליה, aliyah), Bezalel made menorah and incense altar.[14]

Seventh reading—Exodus 38:1–20

In the seventh reading (עליה, aliyah), Bezalel made the altar for sacrifices, laver, and enclosure for the Tabernacle.[15]

Readings according to the triennial cycle

Jews who read the Torah according to the triennial cycle of Torah reading may read the parashah according to a different schedule.[16]

In ancient parallels

The parashah has parallels in these ancient sources:

Exodus chapter 35

Noting that Sargon of Akkad was the first to use a seven-day week, Professor Gregory S. Aldrete of the University of Wisconsin–Green Bay speculated that the Israelites may have adopted the idea from the Akkadian Empire.[17]

Inner-biblical interpretation

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these Biblical sources:[18]

Exodus chapters 25–39

This is the pattern of instruction and construction of the Tabernacle and its furnishings:

| Item | Instruction | Construction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Order | Verses | Order | Verses | |

| The Sabbath | 16 | Exodus 31:12–17 | 1 | Exodus 35:1–3 |

| Contributions | 1 | Exodus 25:1–9 | 2 | Exodus 35:4–29 |

| Craftspeople | 15 | Exodus 31:1–11 | 3 | Exodus 35:30–36:7 |

| Tabernacle | 5 | Exodus 26:1–37 | 4 | Exodus 36:8–38 |

| Ark | 2 | Exodus 25:10–22 | 5 | Exodus 37:1–9 |

| Table | 3 | Exodus 25:23–30 | 6 | Exodus 37:10–16 |

| Menorah | 4 | Exodus 25:31–40 | 7 | Exodus 37:17–24 |

| Altar of Insense | 11 | Exodus 30:1–10 | 8 | Exodus 37:25–28 |

| Anointing Oil | 13 | Exodus 30:22–33 | 9 | Exodus 37:29 |

| Incense | 14 | Exodus 30:34–38 | 10 | Exodus 37:29 |

| Altar of Sacrifice | 6 | Exodus 27:1–8 | 11 | Exodus 38:1–7 |

| Laver | 12 | Exodus 30:17–21 | 12 | Exodus 38:8 |

| Tabernacle Court | 7 | Exodus 27:9–19 | 13 | Exodus 38:9–20 |

| Priestly Garments | 9 | Exodus 28:1–43 | 14 | Exodus 39:1–31 |

| Ordination Ritual | 10 | Exodus 29:1–46 | 15 | Leviticus 8:1–9:24 |

| Lamp | 8 | Exodus 27:20–21 | 16 | Numbers 8:1–4 |

Exodus chapter 35

Exodus 35:1 opens, "And Moses assembled" (וַיַּקְהֵל מֹשֶׁה, vayakhel Mosheh), in an echo of Exodus 32:1, which says, "the people assembled" (וַיִּקָּהֵל הָעָם, vayikahel ha'am).

The Sabbath

Exodus 35:1–3 refers to the Sabbath. Exodus 35:3 prohibits kindling fire on the Sabbath. Numbers 15:32–33 reports that when the Israelites came upon a man gathering wood on the Sabbath (apparently with the intent to fuel a fire), they brought him before Moses, Aaron, and the community and placed him in custody, "because it had not been declared what should be done to him."[19] Clearing up any uncertainty about whether the man had violated the law and what punishment should be given, God told Moses that the whole community was to pelt him with stones outside the camp, which they did.[20]

Commentators note that the Hebrew Bible repeats the commandment to observe the Sabbath 12 times.[21]

Genesis 2:1–3 reports that on the seventh day of Creation, God finished God’s work, rested, and blessed and hallowed the seventh day.

Observance of the Sabbath is one of the Ten Commandments. Exodus 20:8–11 commands that one remember the Sabbath day, keep it holy, and not do any manner of work or cause anyone under one’s control to work, for in six days God made heaven and earth and rested on the seventh day, blessed the Sabbath, and hallowed it. Deuteronomy 5:12–15 commands that one observe the Sabbath day, keep it holy, and not do any manner of work or cause anyone under one’s control to work — so that one’s subordinates might also rest — and remember that the Israelites were servants in the land of Egypt, and God brought them out with a mighty hand and by an outstretched arm.

In the incident of the manna (מָן, man) in Exodus 16:22–30, Moses told the Israelites that the Sabbath is a solemn rest day; prior to the Sabbath one should cook what one would cook, and lay up food for the Sabbath. And God told Moses to let no one go out of one’s place on the seventh day.

In Exodus 31:12–17, just before giving Moses the second Tablets of Stone, God commanded that the Israelites keep and observe the Sabbath throughout their generations, as a sign between God and the children of Israel forever, for in six days God made heaven and earth, and on the seventh day God rested.

In Exodus 35:1–3, just before issuing the instructions for the Tabernacle, Moses again told the Israelites that no one should work on the Sabbath, specifying that one must not kindle fire on the Sabbath.

In Leviticus 23:1–3, God told Moses to repeat the Sabbath commandment to the people, calling the Sabbath a holy convocation.

The prophet Isaiah taught in Isaiah 1:12–13 that iniquity is inconsistent with the Sabbath. In Isaiah 58:13–14, the prophet taught that if people turn away from pursuing or speaking of business on the Sabbath and call the Sabbath a delight, then God will make them ride upon the high places of the earth and will feed them with the heritage of Jacob. And in Isaiah 66:23, the prophet taught that in times to come, from one Sabbath to another, all people will come to worship God.

The prophet Jeremiah taught in Jeremiah 17:19–27 that the fate of Jerusalem depended on whether the people abstained from work on the Sabbath, refraining from carrying burdens outside their houses and through the city gates.

The prophet Ezekiel told in Ezekiel 20:10–22 how God gave the Israelites God’s Sabbaths, to be a sign between God and them, but the Israelites rebelled against God by profaning the Sabbaths, provoking God to pour out God’s fury upon them, but God stayed God’s hand.

.jpg.webp)

In Nehemiah 13:15–22, Nehemiah told how he saw some treading winepresses on the Sabbath, and others bringing all manner of burdens into Jerusalem on the Sabbath day, so when it began to be dark before the Sabbath, he commanded that the city gates be shut and not opened till after the Sabbath and directed the Levites to keep the gates to sanctify the Sabbath.

Exodus chapter 38

2 Chronicles 1:5–6 reports that the bronze altar, which Exodus 38:1–2 reports Bezalel made, still stood before the Tabernacle in Solomon's time, and Solomon sacrificed a thousand burnt offerings on it.

Exodus 38:8 reports that Bezalel made the bronze laver and its base from "the mirrors of the serving women who did service at the door of the tent of meeting." 1 Samuel 2:22 reports that Eli's sons "lay with the women who did service at the door of the tent of meeting."

In early nonrabbinic interpretation

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these early nonrabbinic sources:[22]

Exodus chapter 35

1 Maccabees tells a story related to the Sabbath. 1 Maccabees 2:27–38 told how in the 2nd century BCE, many followers of the pious Jewish priest Mattathias rebelled against the Seleucid king Antiochus IV Epiphanes. Antiochus’s soldiers attacked a group of them on the Sabbath, and when the Pietists failed to defend themselves so as to honor the Sabbath (commanded in, among other places, Exodus 35:1–3), a thousand died. 1 Maccabees 2:39–41 reported that when Mattathias and his friends heard, they reasoned that if they did not fight on the Sabbath, they would soon be destroyed. So they decided that they would fight against anyone who attacked them on the Sabbath.[23]

Josephus taught that when the Israelites brought together the materials with great diligence, Moses set architects over the works by the command of God. And these were the very same people that the people themselves would have chosen, had the election been allowed to them: Bezalel, the son of Uri, of the tribe of Judah, the grandson of Miriam, the sister of Moses, and Oholiab, file son of Ahisamach, of the tribe of Dan.[24]

Classical rabbinic interpretation

.jpg.webp)

The parashah is discussed in these rabbinic sources from the era of the Mishnah and the Talmud:[25]

Exodus chapter 35

The Seder Olam Rabbah taught that Moses descended from Mount Sinai on the 10th of Tishrei—Yom Kippur—and announced that God had shown the Israelites God's pleasure, as Exodus 34:9 says, "You will forgive our crimes and sins and let us inherit," and after that, all the Israelites presented themselves in the assembly that Moses called in Exodus 35:1, and Moses commanded them to build the Tabernacle.[26]

The Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael taught that Exodus 35:1–3 sets forth laws of Sabbath observance here because in Exodus 25:8 God directed, "And let them make Me a sanctuary," and one might have understood that they could build the sanctuary both on weekdays and the Sabbath. The Mekhilta taught that God's direction in Exodus 25:8 to "make Me a sanctuary" applied on all days other than the Sabbath. The Mekhilta posited that one might argue that since the Temple service occurs even on the Sabbath, then perhaps the preparation for the service, without which the priests could not perform the service, could occur even on the Sabbath. One might conclude that if the horn of the altar broke off or a knife became defective, one might repair them on the Sabbath. Exodus 35:1–3 teaches, however, that even such work must be done only on weekdays, and not on the Sabbath.[27]

Rabbi Judah haNasi taught that the words "These are the words" in Exodus 35:1 referred to the 39 labors that God taught Moses at Mount Sinai.[28] Similarly, Rabbi Ḥanina bar Ḥama said that the labors forbidden on the Sabbath in Exodus 35:2 correspond to the 39 labors necessary to construct the Tabernacle.[29]

Tractate Shabbat in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of the Sabbath in Exodus 16:23 and 29; 20:8–11; 23:12; 31:13–17; 35:2–3; Leviticus 19:3; 23:3; Numbers 15:32–36; and Deuteronomy 5:12.[30]

The Mishnah taught that every act that violates the law of the Sabbath also violates the law of a festival, except that one may prepare food on a festival but not on the Sabbath.[31]

A Midrash asked to which commandment Deuteronomy 11:22 refers when it says, "For if you shall diligently keep all this commandment that I command you, to do it, to love the Lord your God, to walk in all His ways, and to cleave to Him, then will the Lord drive out all these nations from before you, and you shall dispossess nations greater and mightier than yourselves." Rabbi Levi said that "this commandment" refers to the recitation of the Shema (Deuteronomy 6:4–9), but the Rabbis said that it refers to the Sabbath, which is equal to all the precepts of the Torah.[32]

The Alphabet of Rabbi Akiva taught that when God was giving Israel the Torah, God told them that if they accepted the Torah and observed God's commandments, then God would give them for eternity a most precious thing that God possessed — the World To Come. When Israel asked to see in this world an example of the World To Come, God replied that the Sabbath is an example of the World To Come.[33]

Reading the words "everyone who profanes [the Sabbath] shall surely be put to death" in Exodus 31:14 (in which the verb for death is doubled), Samuel deduced that the Torah decreed many deaths for desecrating the Sabbath. The Gemara posited that perhaps Exodus 31:14 refers to willful desecration. The Gemara answered that Exodus 31:14 is not needed to teach that willful transgression of the Sabbath is a capital crime, for Exodus 35:2 says, "Whoever does any work therein shall be put to death." The Gemara concluded that Exodus 31:14 thus must apply to an unwitting offender, and in that context, the words "shall surely be put to death" mean that the inadvertent Sabbath violator will "die" monetarily because of the violator's need to bring costly sacrifices.[34]

A Baraita read the words "You shall kindle no fire throughout your habitations upon the Sabbath day" in Exodus 35:3 to teach that only on the Sabbath is kindling fire prohibited, and one may kindle fire on a Festival day, including for purposes other than food preparation.[35]

Rav Huna and Rav Ḥisda reconciled the prohibition of kindling fire on the Sabbath in Exodus 35:3 with the priests' sacrificial duties. The Mishnah taught that the priests could lower the Passover sacrifice into the oven just before nightfall (and leave it to roast on the Sabbath), and the priests could light the fire with chips in the pile in the Temple chamber of the hearth (just before nightfall).[36] Interpreting this Mishnah, Rav Huna cited the prohibition of Exodus 35:3: "You shall kindle no fire throughout your habitations." Rav Huna argued that since Exodus 35:3 says only "throughout your habitations," the priests could kindle the pile in the Temple chamber of the hearth (even on the Sabbath). Rav Ḥisda demurred from Rav Huna's argument, as it would allow kindling even on the Sabbath. Rather, Rav Ḥisda taught that Exodus 35:3 permits only the burning of the limbs and the fat (of animals sacrificed on Friday before nightfall). Rav Ḥisda explained that this burning was allowed because the priests were very particular (in their observance of the Sabbath and would not stoke the fire after nightfall).[37]

The Gemara told that Rav Joseph's wife used to kindle the Sabbath lights late (just before nightfall). Rav Joseph told her that it was taught in a Baraita that the words of Exodus 13:22, "the pillar of cloud by day, and the pillar of fire by night, departed not," teach that the pillar of cloud overlapped the pillar of fire, and the pillar of fire overlapped the pillar of cloud. So she thought of lighting the Sabbath lights very early. But an elder told her that one may kindle when one chooses, provided that one does not light too early (as it would not evidently honor the Sabbath) or too late (later than just before nightfall).[38]

A Baraita taught that a disciple in the name of Rabbi Ishmael noted that the words "in all your dwellings" (בְּכֹל מֹשְׁבֹתֵיכֶם, b'chol moshvoteichem) appear both in the phrase, "You shall kindle no fire throughout your habitations upon the Sabbath day," in Exodus 35:3 and in the phrase, "these things shall be for a statute of judgment unto you throughout your generations in all your dwellings," in Numbers 35:29. The Baraita reasoned from this similar usage that just as the law prohibits kindling fire at home, so the law also prohibits kindling fire in the furtherance of criminal justice. And thus, since some executions require kindling a fire, the Baraita taught that the law prohibits executions on the Sabbath.[39]

Rabbi Hama bar Hanina interpreted the words "the plaited (שְּׂרָד, serad) garments for ministering in the holy place" in Exodus 35:19 to teach that but for the priestly garments described in Exodus 28 (and the atonement achieved by the garments or the priests who wore them), no remnant (שָׂרִיד, sarid) of the Jews would have survived.[40]

Rabbi Levi read Exodus 26:28, regarding "the middle bar in the midst of the boards, which shall pass through from end to end," calculated that the beam must have been 32 cubits in length, and asked where the Israelites would find such a beam in the desert. Rabbi Levi deduced that the Israelites had stored up the cedar to construct the Tabernacle since the days of Jacob. Thus Exodus 35:24 reports, "And every man, with whom was found acacia-wood," not "with whom would be found acacia-wood." Rabbi Levi taught that the Israelites cut the trees down in Magdala of the Dyers near Tiberias and brought them with them to Egypt, and no knot or crack was found in them.[41]

The Rabbis taught in a Baraita that the Tabernacle's lower curtains were made of blue wool, purple wool, crimson wool, and fine linen, while the upper curtains that made the tent spread were made of goats' hair. And they taught that the upper curtains required greater skill than the lower, for Exodus 35:25 says of the lower ones, "And all the women that were wise-hearted did spin with their hands," while Exodus 35:26 says of the upper ones, "And all the women whose heart stirred them up in wisdom spun the goats." It was taught in Rabbi Nehemiah's name that the hair was washed on the goats and spun while still on the goats.[42]

Rabbi Isaac deduced from Exodus 35:30 that we must not appoint a leader over a community without first consulting the community. In Exodus 35:30, Moses said to the Israelites: "See, the Lord has called by name Bezalel, the son of Uri." Rabbi Isaac read Exodus 35:30 to indicate that God asked Moses whether Moses considered Bezalel suitable. Moses replied that if God thought Bezalel suitable, then surely Moses would have to, as well. God told Moses nonetheless to go and consult the Israelites. Moses asked the Israelites whether they considered Bezalel suitable. And they replied that if God and Moses considered him suitable, surely they had to, as well. Rabbi Joḥanan taught that God proclaims three things for God's Self: famine, plenty, and a good leader. 2 Kings 8:1 shows that God proclaims famine, when it says: "The Lord has called for a famine." Ezekiel 36:29 shows that God proclaims plenty, when it says: "I will call for the corn and will increase it." And Exodus 31:1–2 shows that God proclaims a good leader, when it says: "And the Lord spoke to Moses, saying, ‘See I have called by name Bezalel, the son of Uri.'" Rabbi Samuel bar Naḥmani said in the name of Rabbi Joḥanan that Bezalel (בְּצַלְאֵל, whose name can be read בְּצֵל אֶל, betzel El, "in the shadow of God") was so called because of his wisdom. When God told Moses (in Exodus 31:7) to tell Bezalel to make a tabernacle, an ark, and vessels, Moses reversed the order and told Bezalel to make an ark, vessels, and a tabernacle. Bezalel replied to Moses that as a rule, one first builds a house and then brings vessels into it, but Moses directed to make an ark, vessels, and a tabernacle. Bezalel asked where he would put the vessels. And Bezalel asked whether God had told Moses to make a tabernacle, an ark, and vessels. Moses replied that perhaps Bezalel had been in the shadow of God (בְּצֵל אֶל, betzel El) and had thus come to know this.[43]

Rabbi Tanhuma taught in the name of Rav Huna that even the things that Bezalel did not hear from Moses he conceived of on his own exactly as they were told to Moses from Sinai. Rabbi Tanhuma said in the name of Rav Huna that one can deduce this from the words of Exodus 38:22, "And Bezalel the son of Uri, the son of Hur, of the tribe of Judah, made all that the Lord commanded Moses." For Exodus 38:22 does not say, "that Moses commanded him," but, "that the Lord commanded Moses."[44]

And the Agadat Shir ha-Shirim taught that Bezalel and Oholiab went up Mount Sinai, where the heavenly Sanctuary was shown to them.[45]

A Midrash interpreted Exodus 35:30 in light of Ecclesiastes 7:1, "A good name is better than precious oil." The Midrash taught that name of Bezalel was better than precious oil, as Exodus 35:30 proclaims his fame when it says, "See, the Lord has called by name Bezalel." (God proclaimed the name of Bezalel as the Divine architect, while Moses proclaimed the priest as such by anointing with oil.)[46]

Reading the words, "see, the Lord has called by name Bezalel," in Exodus 35:30, a Midrash explained that Israel sinned with fire in making the Golden Calf, as Exodus 32:24 says, "And I cast it into the fire, and there came out this calf." And then Bezalel came and healed the wound (and the construction of the Tabernacle made atonement for the sins of the people in making the Golden Calf). The Midrash likened it to the words of Isaiah 54:16, "Behold, I have created the smith who blows the fire of coals." The Midrash taught that Bezalel was the smith whom God had created to address the fire. And the Midrash likened it to the case of a doctor's disciple who applied a plaster to a wound and healed it. When people began to praise him, his teacher, the doctor, said that they should praise the doctor, for he taught the disciple. Similarly, when everybody said that Bezalel had constructed the Tabernacle through his knowledge and understanding, God said that it was God who created him and taught him, as Isaiah 54:16 says, "Behold, I have created the smith." Thus, Moses said in Exodus 35:30, "see, the Lord has called by name Bezalel."[47]

Exodus 35:30 identifies Bezalel's grandfather as Hur, whom either Rav or Samuel deduced was the son of Miriam and Caleb.[48] A Midrash explained that Exodus 35:30 mentions Hur because when the Israelites were about to serve the Golden Calf, Hur risked his life on God's behalf to prevent them from doing so, and they killed him. Whereupon God assured Hur that God would repay him for his sacrifice. The Midrash likened it to the case of a king whose legions rebelled against him, and his field marshal fought against the rebels, questioning how they could dare rebel against the king. In the end, the rebels killed the field marshal. The king reasoned that if the field marshal had given the king money, the king would have had to repay him. So even more so the king had an obligation to repay the field marshal when he gave his life on the king's behalf. The king rewarded the field marshal by ordaining that all his male offspring would become generals and officers. Similarly, when Israel made the Golden Calf, Hur gave his life for the glory of God. Thus God assured Hur that God would give all Hur's descendants a great name in the world. And thus Exodus 35:30 says, "see, the Lord has called by name Bezalel, the son of Uri, the son of Hur."[49]

Rav Judah taught in the name of Rav that Exodus 35:31 indicated that God endowed Bezalel with the same attribute that God used in creating the universe. Rav Judah said in the name of Rav that Bezalel knew how to combine the letters by which God created the heavens and earth. For Exodus 35:31 says (about Bezalel), "And He has filled him with the spirit of God, in wisdom and in understanding, and in knowledge," and Proverbs 3:19 says (about creation), "The Lord by wisdom founded the earth; by understanding He established the heavens," and Proverbs 3:20 says, "By His knowledge the depths were broken up."[43]

Exodus chapter 36

Doing the math implied by Exodus 36:4, Exodus 38:22, Joshua 14:7, and 1 Chronicles 2:19–20, the Gemara deduced that in earlier generations, a boy of eight could father children. Exodus 38:22 reports that "Bezalel, son of Uri, son of Hur, of the tribe of Judah, made all that the Lord had commanded Moses," when they built the Tabernacle. And 1 Chronicles 2:19–20 reports that Caleb fathered the Hur who fathered Uri who fathered Bezalel. Exodus 36:4 reports that "wise men . . . wrought all the work of the Sanctuary," so Bezalel must have been at least 13 years old to have been a man when he worked on the Tabernacle. A Baraita taught that Moses made the Tabernacle in the first year after the Exodus, and in the second, he erected it and sent out the spies, so the Gemara deduced that Bezalel must have been at least 14 years old when Moses sent out the spies, the year after Bezalel worked on the Tabernacle. And Joshua 14:7 reports that Caleb said that he was 40 years old when Moses sent him to spy out the land. Thus, the Gemara deduced that Caleb was only 26 years older than his great-grandson Bezalel. Deducting two years for the three pregnancies needed to create the three intervening generations, the Gemara concluded that each of Caleb, Hur, and Uri must have conceived his son at the age of eight.[50]

.jpg.webp)

Exodus chapter 37

A Midrash taught that the righteous learn from God's example in creating the world that in beginning any work they should start with light. Thus when God told Moses to build the Tabernacle, Bezalel pondered with what thing he should begin. He concluded that he had better start with the Ark (in which the Israelites would deposit the Torah, the light of the world). And thus Exodus 37:1 commences the report of the construction of the Tabernacle's furnishings, "And Bezalel made the Ark."[51]

Similarly, a Midrash taught that when God told Moses to make the Tabernacle, he came to Bezalel and conveyed the command, and Bezalel asked what the purpose of the Tabernacle was. Moses replied that it was so that God might make God's Shechinah to dwell there and teach the Torah to Israel. Bezalel then asked where the Israelites would keep the Torah. Moses replied that when they had made the Tabernacle, they would then make the Ark. Then Bezalel said that since it would not be fitting for the Torah to be without a home, they should first make the Ark and then the Tabernacle. On that account, Exodus 37:1 associates Bezalel's name with the Ark, saying, "And Bezalel made the Ark."[52]

Reading the words, "Bezalel made the Ark of acacia-wood," in Exodus 37:1, a Midrash taught that God heals with the very thing with which God wounds. Thus, Israel sinned in Shittim (so called because of its many acacia trees), as Numbers 25:1 says, "And Israel abode in Shittim, and the people began to commit harlotry with the daughters of Moab" (and also worshipped the Baal of Peor). But it was also through Shittim wood, or acacia-wood, that God healed the Israelites, for as Exodus 37:1 reports, "Bezalel made the Ark of acacia-wood."[53]

A Baraita taught that Josiah hid away the Ark referred to in Exodus 37:1–5, the anointing oil referred to in Exodus 30:22–33, the jar of manna referred to in Exodus 16:33, Aaron's rod with its almonds and blossoms referred to in Numbers 17:23, and the coffer that the Philistines sent the Israelites as a gift along with the Ark and concerning which the priests said in 1 Samuel 6:8, "And put the jewels of gold, which you returned Him for a guilt offering, in a coffer by the side thereof [of the Ark]; and send it away that it may go." Having observed that Deuteronomy 28:36 predicted, "The Lord will bring you and your king . . . to a nation that you have not known," Josiah ordered the Ark hidden away, as 2 Chronicles 35:3 reports, "And he [Josiah] said to the Levites who taught all Israel, that were holy to the Lord, ‘Put the Holy Ark into the house that Solomon the son of David, King of Israel, built; there shall no more be a burden upon your shoulders; now serve the Lord your God and his people Israel.’" Rabbi Eleazar deduced that Josiah hid the anointing oil and the other objects at the same time as the Ark from the common use of the expressions "there" in Exodus 16:33 with regard to the manna and "there" in Exodus 30:6 with regard to the Ark, "to be kept" in Exodus 16:33 with regard to the manna and "to be kept" in Numbers 17:25 with regard to Aaron's rod, and "generations" in Exodus 16:33 with regard to the manna and "generations" in Exodus 30:31 with regard to the anointing oil.[54]

.jpg.webp)

Exodus chapter 38

A Midrash explained the mirrors of the women who "performed tasks" (הַצֹּבְאֹת, ha-tzovot) at the entrance of the Tent of Meeting in Exodus 38:8. The Midrash told that when the Israelites were suffering hard labor in Egypt, Pharaoh decreed that they should not sleep at home or have sexual relations with their wives. Rabbi Shimon ben Halafta told that the Israelite women would go down to draw water from the river, whereupon God caused them to draw up small fish in their pitchers. The Israelite women would sell some of the fish, cook some of them, buy wine with the proceeds, and go out to the work fields to feed their husbands. After they had eaten, the Israelite women took their mirrors and looked into them together with their husbands. The wives would say that they were better looking than the husbands. The husbands would say that they were better looking. And in this way, they aroused their sexual desire and became fruitful and multiplied, as Exodus 1:7 reports, "And the children of Israel were fruitful and swarmed and multiplied and became exceedingly mighty." It was through the use of these mirrors that the Israelites were able to continue to have children even under the demands of harsh labor. When God told Moses to make the Tabernacle, all of the men came to contribute. Some brought silver, some brought gold or brass, onyx, and other gems to be set. They readily brought everything. The women brought the mirrors and presented them to Moses. When Moses saw the mirrors, he was furious with the women, saying that whoever brought the mirrors should be punished, asking what possible use they could have in the Tabernacle. God told Moses not to look down on them, for it was those mirrors that raised up all of the hosts of children born in Egypt. God thus directed Moses to take them and make from them the washbasin and its base for the priests.[55]

In medieval Jewish interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these medieval Jewish sources:[56]

Exodus chapter 35

In the Zohar, Rabbi Jose expounded on Exodus 35:10: "And let every wise-hearted man among you come and make all that the Lord has commanded." Rabbi Jose taught that when God told Moses in Deuteronomy 1:13, "Get you wise men and men of discernment," Moses searched all of Israel but did not find men of discernment, and so in Deuteronomy 1:15, Moses said, "So I took the heads of your tribes, wise men, and full of knowledge," without mentioning men of discernment. Rabbi Jose deduced that the man of discernment (navan) is of a higher degree than the wise man (hacham), for even a pupil who gives new ideas to a teacher is called "wise." A wise man knows for himself as much as is required, but the man of discernment apprehends the whole, knowing both his own point of view and that of others. Exodus 35:10 uses the term "wise-hearted" because the heart was seen to be the seat of wisdom. Rabbi Jose taught that the man of discernment apprehends the lower world and the upper world, his own being and the being of others.[57]

In modern interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these modern sources:

Exodus chapters 35–39

Noting that Exodus 35–39 repeats material from Exodus 25–31, Julius Popper argued that Exodus 35–39 was a later addition, and the Dutch Protestant theologian Abraham Kuenen and the German biblical scholar Julius Wellhausen agreed.[58] But the mid-20th-century Italian-Israeli scholar Umberto Cassuto, formerly of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, argued that this conjecture was ignorant of ancient Eastern literary style. Cassuto noted that the theme of the founding and building of a shrine was a set literary type in early Eastern writings, and such passages often first recorded the divine utterance describing the plan for the sanctuary and then gave an account of the construction that repeated the description given in the divine communication. Cassuto cited the Ugaritic epic of King Keret, which tells that in a dream, the king received from the god El instructions for the offering of sacrifices, the mustering of an army, the organizing of a military campaign to the land of King Pabel, and the request that Pabel's daughter or granddaughter be given him as a wife. After the instructions, the epic repeats the instructions, varying only the verb forms to the past tense, adding or deleting a conjunction, substituting a synonym, or varying the sequence of words—exactly as Exodus 35–39 does. Cassuto concluded that Exodus 35–39 was thus not a later addition, but required where it is by the literary style.[59] Professor James Kugel of Bar Ilan University wrote that the detailed account must have held a fascination for ancient Israelites who viewed the Tabernacle as highly significant, as the structure that allowed God to reside in the midst of humankind for the first time since the Garden of Eden.[60] And Gunther Plaut cautioned not to approach Exodus 35–39 with modern stylistic prejudices, arguing that a person of the ancient Near East—who was primarily a listener, not a reader—found repetition a welcome way of supporting familiarity with the text, giving assurance that the tradition had been faithfully transmitted.[61]

Exodus chapter 35

Plaut noted that this important chapter in Israel's wilderness story—the order to construct the Tabernacle—begins in Exodus 35:1 with the words "Moses then convoked" (וַיַּקְהֵל מֹשֶׁה, vayakheil Mosheh), heralding the conclusion of the cycle of apostasy and reconciliation that started in Exodus 32:1 with a word with the same spelling and root, "the people gathered themselves" (וַיִּקָּהֵל הָעָם, vayikheil ha-am). In Exodus 32:1, the people assembled to rebel against God's desires in the incident of the Golden Calf, but in Exodus 35:1, with an assembling (וַיַּקְהֵל, vayakheil) that God approved, God demonstrated God's forgiving grace.[62]

Plaut noted that the command to observe the Sabbath in Exodus 35:2–3 preceded the account of the Tabernacle's construction just as it had been commanded at the end of the original instructions in Exodus 31:12–17, so the Sabbath was the bridge that connected the building of the Tabernacle with its deeper purpose.[62] Nahum Sarna wrote that the injunction to observe the Sabbath in Exodus 35:2–3 practically repeats Exodus 31:15 verbatim, with an addition not to kindle fire on the Sabbath. The wording of this prohibition led the Rabbis of the Talmud to understand that fire may not be kindled on the Sabbath itself but may be lit before the Sabbath if not refueled on the Sabbath. The Karaites rejected this interpretation and spent the day without lights (although some later adherents did accept the Rabbinic practice). Sarna wrote that it was probably to demonstrate opposition to the early Karaite view that the Rabbis mandated lighting candles on Friday nights, and to that end, the Geonim (the post-Talmudic heads of the Babylonian academies) instituted the recital of a blessing over them.[63]

Plaut argued that Exodus 35:3 includes the words "throughout your settlements" to make clear that the injunction not to kindle fire on the Sabbath applied not only to the primary prohibition during the building of the Tabernacle, but also in general. Thus Numbers 15:32, reporting a man gathering sticks on the Sabbath, recorded a violation of Exodus 35:3.[64]

In 1950, the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of Conservative Judaism ruled: “Refraining from the use of a motor vehicle is an important aid in the maintenance of the Sabbath spirit of repose. Such restraint aids, moreover, in keeping the members of the family together on the Sabbath. However where a family resides beyond reasonable walking distance from the synagogue, the use of a motor vehicle for the purpose of synagogue attendance shall in no wise be construed as a violation of the Sabbath but, on the contrary, such attendance shall be deemed an expression of loyalty to our faith. . . . [I]n the spirit of a living and developing Halachah responsive to the changing needs of our people, we declare it to be permitted to use electric lights on the Sabbath for the purpose of enhancing the enjoyment of the Sabbath, or reducing personal discomfort in the performance of a mitzvah.”[65]

Professor Carol Meyers of Duke University noted that both women and men provided the materials to which Exodus 25:1–9 and Exodus 35:4–29 refer, as Exodus 35:22 and 29 make clear, including fabrics made and donated by women craftspersons (as indicated in Exodus 35:25–26).[66]

Jeffrey Tigay, Professor Emeritus at the University of Pennsylvania, argued that the word עֲבֹדָה, avodah, in Exodus 35:21, translated as "service" in the New Jewish Publication Society translation (as well as in Exodus 27:19; 30:16; 35:24; 36:1, 3, 5; and 39:40) is better rendered "labor" (referring to construction), as the materials contributed were for the construction of the Tabernacle, not for the worship that would be conducted there afterwards.[67]

Exodus chapter 37

Exodus 37:24 speaks of "a talent of pure gold." This table translates units of weight used in the Bible into their modern equivalents:[68]

| Unit | Texts | Ancient Equivalent | Modern Equivalent |

|---|---|---|---|

| gerah (גֵּרָה) | Exodus 30:13; Leviticus 27:25; Numbers 3:47; 18:16; Ezekiel 45:12 | 1/20 shekel | 0.6 gram; 0.02 ounce |

| bekah (בֶּקַע) | Genesis 24:22; Exodus 38:26 | 10 gerahs; half shekel | 6 grams; 0.21 ounce |

| pim (פִים) | 1 Samuel 13:21 | 2/3 shekel | 8 grams; 0.28 ounce |

| shekel (שֶּׁקֶל) | Exodus 21:32; 30:13, 15, 24; 38:24, 25, 26, 29 | 20 gerahs; 2 bekahs | 12 grams; 0.42 ounce |

| mina (maneh, מָּנֶה) | 1 Kings 10:17; Ezekiel 45:12; Ezra 2:69; Nehemiah 7:70 | 50 shekels | 0.6 kilogram; 1.32 pounds |

| talent (kikar, כִּכָּר) | Exodus 25:39; 37:24; 38:24, 25, 27, 29 | 3,000 shekels; 60 minas | 36 kilograms; 79.4 pounds |

Commandments

According to Maimonides and Sefer ha-Chinuch, there is one negative commandment in the parashah:[69]

- The court must not inflict punishment on the Sabbath.[70]

Liturgy

Following the Kabbalat Shabbat prayer service and prior to the Friday evening (Ma'ariv) service, Jews traditionally read rabbinic sources on the observance of the Sabbath, starting with Mishnah Shabbat 2:5.[71] Mishnah Shabbat 2:5, in turn, interprets the laws of kindling lights in Exodus 35:3.[72]

Haftarah

Parashat Vayakhel

When Parashat Vayakhel is read alone, the haftarah is:

- for Ashkenazi Jews: 1 Kings 7:40–50

- for Sephardi Jews: 1 Kings 7:13–26

Ashkenazi—1 Kings 7:40–50

Both the parashah and the haftarah in 1 Kings 7 report the leader's erection of the holy place, Moses' building of the Tabernacle in the parashah,[73] and Solomon's building of the Temple in Jerusalem in the haftarah.[74] Both the parashah and the haftarah note particular metals for the holy space.[75]

Sephardi—1 Kings 7:13–26

Both the parashah and the haftarah note the skill (chokhmah), ability (tevunah), and knowledge (da‘at), of the artisan (Bezalel in the parashah, Hiram in the haftarah) in every craft (kol mela'khah).[76]

Shabbat Shekalim

When Parashat Vayakhel coincides with the special Sabbath Shabbat Shekalim, (as it does in 2019), the haftarah is 2 Kings 12:1–17.

Parashat Vayakhel–Pekudei

When Parashat Vayakhel is combined with Parashat Pekudei, the haftarah is:

- for Ashkenazi Jews: 1 Kings 7:51–8:21

- for Sephardi Jews: 1 Kings 7:40–50

Shabbat HaChodesh

When the parashah coincides with Shabbat HaChodesh ("Sabbath [of] the month," the special Sabbath preceding the Hebrew month of Nissan (as it did in 2013 and 2017), the haftarah is:

- for Ashkenazi Jews: Ezekiel 45:16–46:18

- for Sephardi Jews: Ezekiel 45:18–46:15

On Shabbat HaChodesh, Jews read Exodus 12:1–20, in which God commands that "This month [Nissan] shall be the beginning of months; it shall be the first month of the year,"[77] and in which God issued the commandments of Passover.[78] Similarly, the haftarah in Ezekiel 45:21–25 discusses Passover. In both the special reading and the haftarah, God instructs the Israelites to apply blood to doorposts.[79]

Shabbat Parah

When the parashah coincides with Shabbat Parah (one of the special Sabbaths prior to Passover—as it did in 2018), the haftarah is:

- for Ashkenazi Jews: Ezekiel 36:16–38

- for Sephardi Jews: Ezekiel 36:16–36

On Shabbat Parah, the Sabbath of the red heifer, Jews read Numbers 19:1–22, which describes the rites of purification using the red heifer (parah adumah). Similarly, the haftarah in Ezekiel 36 also describes purification. In both the special reading and the haftarah in Ezekiel 36, sprinkled water cleansed the Israelites.[80]

Notes

- "Torah Stats for Shemoth," Akhlah Inc.

- "Parashat Vayakhel". Hebcal. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Shemos/Exodus. Edited by Menachem Davis, pages 263–80. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2008.

- Exodus 35:1–3.

- Exodus 35:4–9.

- Exodus 35:10–19.

- Exodus 35:21–29.

- Exodus 35:30–35.

- Exodus 36:1–2.

- Exodus 36:3–7.

- Exodus 36:8–19.

- Exodus 36:20–38.

- Exodus 37:1–16.

- Exodus 37:17–29.

- Exodus 38:1–20.

- See, e.g., Richard Eisenberg, "A Complete Triennial Cycle for Reading the Torah," in Proceedings of the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Conservative Movement: 1986–1990 (New York: The Rabbinical Assembly, 2001), pages 383–418.

- Gregory S. Aldrete, "From Out of the Mesopotamian Mud," in "History of the Ancient World: A Global Perspective" (Chantilly, Virginia: The Great Courses, 2011), lecture 2.

- For more on inner-Biblical interpretation, see, e.g., Benjamin D. Sommer. "Inner-biblical Interpretation." In The Jewish Study Bible: Second Edition. Edited by Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, pages 1835–41. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

- Numbers 15:34.

- Numbers 15:35–36.

- The Sabbath Anthology. Edited by Abraham E. Millgram, page 203. Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society, 1944; reprinted 2018.

- For more on early nonrabbinic interpretation, see, e.g., Esther Eshel. "Early Nonrabbinic Interpretation." In The Jewish Study Bible: Second Edition. Edited by Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, pages 1841–59.

- Jonathan A. Goldstein, translator, I Maccabees (New York: Doubleday and Company, 1976), pages 5, 234–35.

- Josephus. Antiquities of the Jews book 3, chapter 6, paragraph 1, clause 104.

- For more on classical rabbinic interpretation, see, e.g., Yaakov Elman. "Classical Rabbinic Interpretation." In The Jewish Study Bible: Second Edition. Edited by Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, pages 1859–78.

- Seder Olam Rabbah, chapter 6.

- Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael 35:1.

- Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 97b.

- Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 49b.

- Mishnah Shabbat 1:1–24:5; Tosefta Shabbat 1:1–17:29; Jerusalem Talmud Shabbat 1a–113b; Talmud Shabbat 2a–157b.

- Mishnah Beitzah 5:2; Babylonian Talmud Beitzah 36b; see also Mishnah Megillah 1:5; Babylonian Talmud Megillah 7b.

- Deuteronomy Rabbah 4:4.

- Alphabet of Rabbi Akiva, quoted in Abraham Joshua Heschel, The Sabbath (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1951), page 73.

- Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 70a.

- Jerusalem Talmud Beitzah 47a; see also Mekhilta 82:1:9.

- Mishnah Shabbat 1:11; Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 19b.

- Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 20a.

- Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 23b.

- Babylonian Talmud Yevamot 6b–7a.

- Babylonian Talmud Yoma 72a–b.

- Genesis Rabbah 94:4.

- Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 99a.

- Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 55a.

- Jerusalem Talmud Peah 5a.

- Agadat Shir ha-Shirim 5, 36–37. Quoted in Louis Ginzberg. Legends of the Jews, volume 6, page 63. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1928.

- Exodus Rabbah 48:1.

- Exodus Rabbah 48:5.

- Babylonian Talmud Sotah 11b.

- Exodus Rabbah 48:3.

- Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 69b.

- Exodus Rabbah 50:1.

- Exodus Rabbah 50:2.

- Exodus Rabbah 50:3.

- Babylonian Talmud Horayot 12a.

- Midrash Tanhuma Pekudei 9.

- For more on medieval Jewish interpretation, see, e.g., Barry D. Walfish. "Medieval Jewish Interpretation." In The Jewish Study Bible: Second Edition. Edited by Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, pages 1891–915.

- Zohar, Shemot, part 2, page 201a. Spain, late 13th century. In, e.g., The Zohar: Pritzker Edition. Translation and commentary by Daniel C. Matt, volume 6, pages 145–46. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2011.

- See Umberto Cassuto. A Commentary on the Book of Exodus. Jerusalem, 1951. Translated by Israel Abrahams, pages 452–53. Jerusalem: The Magnes Press, The Hebrew University, 1967.

- Umberto Cassuto. A Commentary on the Book of Exodus. Translated by Israel Abrahams, page 453.

- James L. Kugel. How To Read the Bible: A Guide to Scripture, Then and Now, pages 289. New York: Free Press, 2007.

- W. Gunther Plaut. The Torah: A Modern Commentary: Revised Edition. Revised edition edited by David E.S. Stern, page 621. New York: Union for Reform Judaism, 2006.

- W. Gunther Plaut. The Torah: A Modern Commentary: Revised Edition. Revised edition edited by David E.S. Stern, page 611.

- Nahum M. Sarna. The JPS Torah Commentary: Exodus: The Traditional Hebrew Text with the New JPS Translation, page 222. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1991.

- W. Gunther Plaut. The Torah: A Modern Commentary: Revised Edition. Revised edition edited by David E.S. Stern, page 612.

- Morris Adler, Jacob B. Agus, and Theodore Friedman. “Responsum on the Sabbath.” Proceedings of the Rabbinical Assembly, volume 14 (1950), pages 112–88. New York: Rabbinical Assembly of America, 1951. In Proceedings of the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Conservative Movement 1927–1970, volume 3 (Responsa), pages 1109–34. Jerusalem: The Rabbinical Assembly and The Institute of Applied Hallakhah, 1997.

- Carol Meyers. "Exodus." In The New Oxford Annotated Bible: New Revised Standard Version With The Apocrypha: An Ecumenical Study Bible. Edited by Michael D. Coogan, Marc Z. Brettler, Carol A. Newsom, and Pheme Perkins, pages 133–34. New York: Oxford University Press, Revised 4th Edition 2010.

- Jeffrey H. Tigay. "Exodus." In The Jewish Study Bible: Second Edition. Edited by Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, page 183.

- Bruce Wells. "Exodus." In Zondervan Illustrated Bible Backgrounds Commentary. Edited by John H. Walton, volume 1, page 258. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan, 2009.

- See, e.g., Maimonides. The Commandments: Sefer Ha-Mitzvoth of Maimonides. Translated by Charles B. Chavel, volume 2, page 297. London: Soncino Press, 1967. Sefer HaHinnuch: The Book of [Mitzvah] Education. Translated by Charles Wengrov, volume 1, pages 431–33. Jerusalem: Feldheim Publishers, 1991.

- Exodus 35:3.

- Mishnah Shabbat 2:5. In, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, page 182.

- Reuven Hammer. Or Hadash: A Commentary on Siddur Sim Shalom for Shabbat and Festivals, page 25. New York: The Rabbinical Assembly, 2003.

- Exodus 35:4–38:20.

- 1 Kings 7:40–50.

- Exodus 35:5; 1 Kings 7:45, 47–50.

- Exodus 35:30–31; 1 Kings 7:14.

- Exodus 12:2.

- Exodus 12:3–20.

- Exodus 12:7; Ezekiel 45:19.

- Numbers 19:18; Ezekiel 36:25.

Further reading

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these sources:

Ancient

- The Ba‘lu Myth. Ugarit, 2nd millennium BCE. In The Context of Scripture, Volume I: Canonical Compositions from the Biblical World, pages 260–61. Edited by William W. Hallo. Pilgrim Press, 1997. (building of a palace for Ba'al).

Biblical

- Isaiah 56:6–7 (keeping the Sabbath); 66:23 (universally observed Sabbath).

- Psalms 26:6 (washing, altar); 51:16–19 (sacrifices); 80:2 (cherubim); 84:2–3, 11 (Tabernacle, courts); 92:14 (courts); 96:6 (God's sanctuary); 100:4 (court of the Tabernacle); 134:2 (God's sanctuary); 141:2 (incense); 150:1 (God's sanctuary).

Early nonrabbinic

- Philo. Allegorical Interpretation 3:33:101; On the Migration of Abraham 17:97–98. Alexandria, Egypt, early 1st century CE. In, e.g., The Works of Philo: Complete and Unabridged, New Updated Edition. Translated by Charles Duke Yonge, pages 61, 262. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 1993.

- Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 3:6:1–10:1. Circa 93–94. In, e.g., The Works of Josephus: Complete and Unabridged, New Updated Edition. Translated by William Whiston, pages 85–95. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 1987.

Classical rabbinic

- Seder Olam Rabbah, chapter 6. 2nd century CE. In, e.g., Seder Olam: The Rabbinic View of Biblical Chronology. Translated and with commentary by Heinrich W. Guggenheimer, pages 73–78. Lanham, Maryland: Jason Aronson, 1998.

- Mishnah: Shabbat 1:1–24:5; Beitzah 5:2; Megillah 1:5. Land of Israel, circa 200 CE. In, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, pages 179–208, 298, 317. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988.

- Tosefta Shabbat 1:1–17:29. Land of Israel, circa 250 CE. In, e.g., The Tosefta: Translated from the Hebrew, with a New Introduction. Translated by Jacob Neusner, volume 1, pages 357–427. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 2002.

- Mekhilta According to Rabbi Ishmael 82:1. Land of Israel, late 4th century. In, e.g., Mekhilta According to Rabbi Ishmael. Translated by Jacob Neusner, volume 2, pages 258–62. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1988.

- Jerusalem Talmud: Terumot 31b; Shabbat 1a–113b; Shekalim 2a, 48b; Beitzah 47a; Nazir 21a, 25b–26a; Sotah 16b; Sanhedrin 27b; Shevuot 1b. Tiberias, Land of Israel, circa 400 CE. In, e.g., Talmud Yerushalmi. Edited by Chaim Malinowitz, Yisroel Simcha Schorr, and Mordechai Marcus, volumes 7, 13–15, 20, 23, 34–36, 44, 46. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2010–2020. And in, e.g., The Jerusalem Talmud: A Translation and Commentary. Edited by Jacob Neusner and translated by Jacob Neusner, Tzvee Zahavy, B. Barry Levy, and Edward Goldman. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 2009.

.jpg.webp)

- Genesis Rabbah 94:4. Land of Israel, 5th century. In, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Genesis. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 2, page 871. London: Soncino Press, 1939.

- Midrash Tanhuma Vayakhel. 5th–10th centuries. In, e.g., The Metsudah Midrash Tanchuma: Shemos II. Translated and annotated by Avrohom Davis; edited by Yaakov Y.H. Pupko, volume 4 (Shemos volume 2), pages 339–89. Monsey, New York: Eastern Book Press, 2004.

- Babylonian Talmud: Babylonian Berakhot 55a; Shabbat 20a, 49b, 70a, 74b, 96b; Eruvin 2b; Yoma 66b, 72b, 75a; Beitzah 4b, 36b; Rosh Hashanah 34a; Megillah 7b; Chagigah 10a–b; Yevamot 6b–7a, 33b; Sotah 3a; Kiddushin 37a; Bava Kamma 2a, 54a, 71a; Sanhedrin 35b, 69b; Makkot 21b; Shevuot 26b; Avodah Zarah 12b, 24a; Zevachim 59b; Bekhorot 41a. Babylonia, 6th century. In, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr, Chaim Malinowitz, and Mordechai Marcus, 72 volumes. Brooklyn: Mesorah Pubs., 2006.

Medieval

- Bede. Of the Tabernacle and Its Vessels, and of the Priestly Vestments. Monkwearmouth, England, 720s. In Bede: On the Tabernacle. Translated with notes and introduction by Arthur G. Holder. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1994.

- Exodus Rabbah 48:1–50:5. 10th century. In, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Exodus. Translated by S. M. Lehrman, volume 3, pages 546–61. London: Soncino Press, 1939.

- Solomon ibn Gabirol. A Crown for the King, 9:105–06. Spain, 11th century. Translated by David R. Slavitt, pages 14–15. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

- Rashi. Commentary. Exodus 35–38. Troyes, France, late 11th century. In, e.g., Rashi. The Torah: With Rashi's Commentary Translated, Annotated, and Elucidated. Translated and annotated by Yisrael Isser Zvi Herczeg, volume 2, pages 487–505. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1994.

- Rashbam. Commentary on the Torah. Troyes, early 12th century. In, e.g., Rashbam's Commentary on Exodus: An Annotated Translation. Edited and translated by Martin I. Lockshin, pages 425–29. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1997.

- Abraham ibn Ezra. Commentary on the Torah. France, 1153. In, e.g., Ibn Ezra's Commentary on the Pentateuch: Exodus (Shemot). Translated and annotated by H. Norman Strickman and Arthur M. Silver, volume 2, pages 730–46. New York: Menorah Publishing Company, 1996.

- Maimonides. The Guide for the Perplexed. Cairo, Egypt, 1190. In, e.g., Moses Maimonides. The Guide for the Perplexed. Translated by Michael Friedländer, pages 29–31, 393, 397. New York: Dover Publications, 1956.

- Hezekiah ben Manoah. Hizkuni. France, circa 1240. In, e.g., Chizkiyahu ben Manoach. Chizkuni: Torah Commentary. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 3, pages 645–50. Jerusalem: Ktav Publishers, 2013.

- Naḥmanides. Commentary on the Torah. Jerusalem, circa 1270. In, e.g., Ramban (Naḥmanides): Commentary on the Torah. Translated by Charles B. Chavel, volume 2, pages 595–608. New York: Shilo Publishing House, 1973.

- Zohar 2:194b–220a. Spain, late 13th century.

- Bahya ben Asher. Commentary on the Torah. Spain, early 14th century. In, e.g., Midrash Rabbeinu Bachya: Torah Commentary by Rabbi Bachya ben Asher. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 4, pages 1418–38. Jerusalem: Lambda Publishers, 2003.

- Jacob ben Asher (Baal Ha-Turim). Commentary on the Torah. Early 14th century. In, e.g., Baal Haturim Chumash: Shemos/Exodus. Translated by Eliyahu Touger; edited and annotated by Avie Gold, volume 2, pages 929–57. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2000.

- Isaac ben Moses Arama. Akedat Yizhak (The Binding of Isaac). Late 15th century. In, e.g., Yitzchak Arama. Akeydat Yitzchak: Commentary of Rabbi Yitzchak Arama on the Torah. Translated and condensed by Eliyahu Munk, volume 1, pages 519–35. New York, Lambda Publishers, 2001.

Modern

- Isaac Abravanel. Commentary on the Torah. Italy, between 1492–1509. In, e.g., Abarbanel: Selected Commentaries on the Torah: Volume 2: Shemos/Exodus. Translated and annotated by Israel Lazar, pages 404–20. Brooklyn: CreateSpace, 2015.

- Abraham Saba. Ẓeror ha-Mor (Bundle of Myrrh). Fez, Morocco, circa 1500. In, e.g., Tzror Hamor: Torah Commentary by Rabbi Avraham Sabba. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 3, pages 1221–28. Jerusalem, Lambda Publishers, 2008.

- Obadiah ben Jacob Sforno. Commentary on the Torah. Venice, 1567. In, e.g., Sforno: Commentary on the Torah. Translation and explanatory notes by Raphael Pelcovitz, pages 474–85. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1997.

- Moshe Alshich. Commentary on the Torah. Safed, circa 1593. In, e.g., Moshe Alshich. Midrash of Rabbi Moshe Alshich on the Torah. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 2, pages 607–14. New York, Lambda Publishers, 2000.

- Shlomo Ephraim Luntschitz. Kli Yakar. Lublin, 1602. In, e.g., Kli Yakar: Shemos. Translated by Elihu Levine, volume 2, pages 345–71. Southfield, Michigan: Targum Press/Feldheim Publishers, 2007.

- Avraham Yehoshua Heschel. Commentaries on the Torah. Cracow, Poland, mid 17th century. Compiled as Chanukat HaTorah. Edited by Chanoch Henoch Erzohn. Piotrkow, Poland, 1900. In Avraham Yehoshua Heschel. Chanukas HaTorah: Mystical Insights of Rav Avraham Yehoshua Heschel on Chumash. Translated by Avraham Peretz Friedman, pages 199–202. Southfield, Michigan: Targum Press/Feldheim Publishers, 2004.

.jpg.webp)

- Thomas Hobbes. Leviathan, 3:34. England, 1651. Reprint edited by C. B. Macpherson, page 431. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Classics, 1982.

- Edward Taylor. "18. Meditation. Heb. 13.10. Wee Have an Altar." In Preliminary Meditations: First Series. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Early 18th century. In Harold Bloom. American Religious Poems, pages 21–22. New York: Library of America, 2006.

- Chaim ibn Attar. Ohr ha-Chaim. Venice, 1742. In Chayim ben Attar. Or Hachayim: Commentary on the Torah. Translated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 2, pages 894–909. Brooklyn: Lambda Publishers, 1999.

- Yitzchak Magriso. Me'am Lo'ez. Constantinople, 1746. In Yitzchak Magriso. The Torah Anthology: Me'am Lo'ez. Translated by Aryeh Kaplan, volume 10, pages 175–248. Jerusalem: Moznaim Publishing, 1991.

- Naḥman of Breslov. Teachings. Bratslav, Ukraine, before 1811. In Rebbe Nachman's Torah: Breslov Insights into the Weekly Torah Reading: Exodus-Leviticus. Compiled by Chaim Kramer; edited by Y. Hall, pages 282–91. Jerusalem: Breslov Research Institute, 2011.

.crop.jpg.webp)

- Samson Raphael Hirsch. The Pentateuch: Exodus. Translated by Isaac Levy, volume 2, pages 664–94. Gateshead: Judaica Press, 2nd edition 1999. Originally published as Der Pentateuch uebersetzt und erklaert. Frankfurt, 1867–1878.

- Samuel David Luzzatto (Shadal). Commentary on the Torah. Padua, 1871. In, e.g., Samuel David Luzzatto. Torah Commentary. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 3, pages 894–95. New York: Lambda Publishers, 2012.

- Samson Raphael Hirsch. The Jewish Sabbath. Frankfurt, before 1889. Translated by Ben Josephussoro. 1911. Reprinted Lexington, Kentucky: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2014.

- Yehudah Aryeh Leib Alter. Sefat Emet. Góra Kalwaria (Ger), Poland, before 1906. Excerpted in The Language of Truth: The Torah Commentary of Sefat Emet. Translated and interpreted by Arthur Green, pages 135–38. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1998. Reprinted 2012.

- Alexander Alan Steinbach. Sabbath Queen: Fifty-four Bible Talks to the Young Based on Each Portion of the Pentateuch, pages 68–70. New York: Behrman's Jewish Book House, 1936.

- Benno Jacob. The Second Book of the Bible: Exodus. London, 1940. Translated by Walter Jacob, pages 1007–31. Hoboken, New Jersey: KTAV Publishing House, 1992.

- The Sabbath Anthology. Edited by Abraham E. Millgram. Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society, 1944; reprinted 2018. (Exodus 35:1–3).

- Morris Adler, Jacob B. Agus, and Theodore Friedman. “Responsum on the Sabbath.” Proceedings of the Rabbinical Assembly, volume 14 (1950), pages 112–88. New York: Rabbinical Assembly of America, 1951. In Proceedings of the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Conservative Movement 1927–1970, volume 3 (Responsa), pages 1109–34. Jerusalem: The Rabbinical Assembly and The Institute of Applied Hallakhah, 1997.

- Umberto Cassuto. A Commentary on the Book of Exodus. Jerusalem, 1951. Translated by Israel Abrahams, pages 452–68. Jerusalem: The Magnes Press, The Hebrew University, 1967.

- Abraham Joshua Heschel. The Sabbath. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1951. Reprinted 2005.

- Morris Adler. The World of the Talmud, pages 28–29. B'nai B'rith Hillel Foundations, 1958. Reprinted Kessinger Publishing, 2007.

- Gerhard von Rad. "The Tent and the Ark." In The Problem of the Hexateuch and Other Essays, pages 103–24. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1966. LCCN 66-11432.

- Elie Munk. The Call of the Torah: An Anthology of Interpretation and Commentary on the Five Books of Moses. Translated by E.S. Mazer, volume 2, pages 505–29. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1995. Originally published as La Voix de la Thora. Paris: Fondation Samuel et Odette Levy, 1981.

- Victor (Avigdor) Hurowitz. "The Priestly Account of Building the Tabernacle." Journal of the American Oriental Society, volume 105 (number 1) (January–March 1985): pages 21–30.

- Pinchas H. Peli. Torah Today: A Renewed Encounter with Scripture, pages 95–98. Washington, D.C.: B'nai B'rith Books, 1987.

- Craig R. Koester. Dwelling of God: The Tabernacle in the Old Testament, Intertestamental Jewish Literature, and the New Testament. Washington: Catholic Biblical Association of America, 1989.

- Harvey J. Fields. A Torah Commentary for Our Times: Volume II: Exodus and Leviticus, pages 86–94. New York: UAHC Press, 1991.

- Nahum M. Sarna. The JPS Torah Commentary: Exodus: The Traditional Hebrew Text with the New JPS Translation, pages 222–31. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1991.

- Neḥama Leibowitz. New Studies in Shemot (Exodus), volume 2, pages 644–88. Jerusalem: Haomanim Press, 1993. Reprinted as New Studies in the Weekly Parasha. Lambda Publishers, 2010.

- Walter Brueggemann. "The Book of Exodus." In The New Interpreter's Bible. Edited by Leander E. Keck, volume 1, pages 957–74. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1994.

- Judith S. Antonelli. "Women's Wisdom." In In the Image of God: A Feminist Commentary on the Torah, pages 221–30. Northvale, New Jersey: Jason Aronson, 1995.

- Ellen Frankel. The Five Books of Miriam: A Woman’s Commentary on the Torah, pages 142–45. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1996.

- W. Gunther Plaut. The Haftarah Commentary, pages 217–21. New York: UAHC Press, 1996.

- Robert Goodman. "Shabbat." In Teaching Jewish Holidays: History, Values, and Activities, pages 1–19. Denver: A.R.E. Publishing, 1997.

- Sorel Goldberg Loeb and Barbara Binder Kadden. Teaching Torah: A Treasury of Insights and Activities, pages 148–54. Denver: A.R.E. Publishing, 1997.

- Exodus to Deuteronomy: A Feminist Companion to the Bible (Second Series). Edited by Athalya Brenner, pages 34, 38–39. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2000.

- Edward L. Greenstein. “Recovering ‘The Women Who Served at the Entrance.’” In Gershon Galil and Moshe Weinfeld, editors. Studies in Historical Geography and Biblical Historiography: Presented to Zecharia Kallai, pages 165–73. Leiden: Brill, 2000.

- Carol Meyers. “Women at the Entrance to the Tent of Meeting.” In Women in Scripture: A Dictionary of Named and Unnamed Women in the Hebrew Bible, the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books and New Testament. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2000.

- Nancy H. Wiener. "Of Women and Mirrors." In The Women's Torah Commentary: New Insights from Women Rabbis on the 54 Weekly Torah Portions. Edited by Elyse Goldstein, pages 172–78. Woodstock, Vermont: Jewish Lights Publishing, 2000.

- Martin R. Hauge. The Descent from the Mountain: Narrative Patterns in Exodus 19–40. Sheffield: Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Press, 2001.

- Avivah Gottlieb Zornberg. The Particulars of Rapture: Reflections on Exodus, pages 461–98. New York: Doubleday, 2001.

- Lainie Blum Cogan and Judy Weiss. Teaching Haftarah: Background, Insights, and Strategies, pages 138–51. Denver: A.R.E. Publishing, 2002.

- Michael Fishbane. The JPS Bible Commentary: Haftarot, pages 135–46. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2002.

- Alan Lew. This Is Real and You Are Completely Unprepared: The Days of Awe as a Journey of Transformation, pages 53–55. Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 2003.

- Martha Lynn Wade. Consistency of Translation Techniques in the Tabernacle Accounts of Exodus in the Old Greek. Society of Biblical Literature, 2003.

- Robert Alter. The Five Books of Moses: A Translation with Commentary, pages 514–25. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2004.

- Jeffrey H. Tigay. "Exodus." In The Jewish Study Bible. Edited by Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, pages 191–97. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Professors on the Parashah: Studies on the Weekly Torah Reading Edited by Leib Moscovitz, pages 150–54. Jerusalem: Urim Publications, 2005.

- W. Gunther Plaut. The Torah: A Modern Commentary: Revised Edition. Revised edition edited by David E.S. Stern, pages 611–26. New York: Union for Reform Judaism, 2006.

- William H.C. Propp. Exodus 19–40, volume 2A, pages 624–722. New York: Anchor Bible, 2006.

- Suzanne A. Brody. "Successful Campaign." In Dancing in the White Spaces: The Yearly Torah Cycle and More Poems, page 84. Shelbyville, Kentucky: Wasteland Press, 2007.

- James L. Kugel. How To Read the Bible: A Guide to Scripture, Then and Now, pages 289, 291, 486. New York: Free Press, 2007.

- Kenton L. Sparks. “‘Enūma Elish’ and Priestly Mimesis: Elite Emulation in Nascent Judaism.” Journal of Biblical Literature, volume 126 (2007): 637–42. (“Priestly Mimesis in the Tabernacle Narrative (Exodus 25–40)”).

- The Torah: A Women's Commentary. Edited by Tamara Cohn Eskenazi and Andrea L. Weiss, pages 521–44. New York: URJ Press, 2008.

- Thomas B. Dozeman. Commentary on Exodus, pages 756–59. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2009.

- Jill Hammer. "Listening to Heart-Wisdom: Parashat Vayakhel (Exodus 35:1–38:20)." In Torah Queeries: Weekly Commentaries on the Hebrew Bible. Edited by Gregg Drinkwater, Joshua Lesser, and David Shneer; foreword by Judith Plaskow, pages 113–16. New York: New York University Press, 2009.

- Reuven Hammer. Entering Torah: Prefaces to the Weekly Torah Portion, pages 131–34. New York: Gefen Publishing House, 2009.

- Rebecca G.S. Idestrom. "Echoes of the Book of Exodus in Ezekiel." Journal for the Study of the Old Testament, volume 33 (number 4) (June 2009): pages 489–510. (Motifs from Exodus found in Ezekiel, including the call narrative, divine encounters, captivity, signs, plagues, judgment, redemption, tabernacle/temple, are considered.).

- Bruce Wells. "Exodus." In Zondervan Illustrated Bible Backgrounds Commentary. Edited by John H. Walton, volume 1, pages 264–65. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan, 2009.

- Jonathan Sacks. Covenant & Conversation: A Weekly Reading of the Jewish Bible: Exodus: The Book of Redemption, pages 277–301. Jerusalem: Maggid Books, 2010.

- Joe Lieberman and David Klinghoffer. The Gift of Rest: Rediscovering the Beauty of the Sabbath. New York: Howard Books, 2011.

- James W. Watts. "Aaron and the Golden Calf in the Rhetoric of the Pentateuch." Journal of Biblical Literature, volume 130 (number 3) (fall 2011): pages 417–30.

- William G. Dever. The Lives of Ordinary People in Ancient Israel: When Archaeology and the Bible Intersect, page 245. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2012.

- Shmuel Herzfeld. "Inspirational Snapshots from Eretz Yisrael." In Fifty-Four Pick Up: Fifteen-Minute Inspirational Torah Lessons, pages 128–34. Jerusalem: Gefen Publishing House, 2012.

- Daniel S. Nevins. "The Use of Electrical and Electronic Devices on Shabbat." New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 2012.

- Torah MiEtzion: New Readings in Tanach: Shemot. Edited by Ezra Bick and Yaakov Beasley, pages 480–530. Jerusalem: Maggid Books, 2012.

- Michael B. Hundley. Gods in Dwellings: Temples and Divine Presence in the Ancient Near East. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2013.

- Amiel Ungar. "Tel Aviv and the Sabbath." The Jerusalem Report, volume 24 (number 8) (July 29, 2013): page 37.

- Amanda Terkel. "Glenn Grothman, Wisconsin GOP Senator, Fights for a Seven-Day Workweek." The Huffington Post. (January 3, 2014, updated January 23, 2014). (A Congressional candidate said, "Right now in Wisconsin, you're not supposed to work seven days in a row, which is a little ridiculous because all sorts of people want to work seven days a week.").

- Jonathan Sacks. Lessons in Leadership: A Weekly Reading of the Jewish Bible, pages 111–14. New Milford, Connecticut: Maggid Books, 2015.

- Raanan Eichler. "The Poles of the Ark: On the Ins and Outs of a Textual Contradiction." Journal of Biblical Literature, volume 135, number 4 (Winter 2016): pages 733–4.

- Jonathan Sacks. Essays on Ethics: A Weekly Reading of the Jewish Bible, pages 137–43. New Milford, Connecticut: Maggid Books, 2016.

- Shai Held. The Heart of Torah, Volume 1: Essays on the Weekly Torah Portion: Genesis and Exodus, pages 213–20. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2017.

- Steven Levy and Sarah Levy. The JPS Rashi Discussion Torah Commentary, pages 68–70. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2017.

External links

Commentaries

- Academy for Jewish Religion, California

- Aish.com

- American Jewish University - Ziegler School of Rabbinic Studies

- Chabad.org

- Hadar

- Jewish Theological Seminary

- MyJewishLearning.com

- Orthodox Union

- Pardes from Jerusalem

- Reconstructing Judaism

- Sephardic Institute

- Union for Reform Judaism

- United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism

- Yeshiva University