Exophiala dermatitidis

Exophiala dermatitidis is a thermophilic black yeast, and a member of the Herpotrichiellaceae.[8][9] While the species is only found at low abundance in nature, metabolically active strains are commonly isolated in saunas, steam baths, and dish washers.[9][10] Exophiala dermatitidis only rarely causes infection in humans, however cases have been reported around the world. In East Asia, the species has caused lethal brain infections in young and otherwise healthy individuals.[11] The fungus has been known to cause cutaneous and subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis,[12][13] and as a lung colonist in people with cystic fibrosis in Europe.[14] In 2002, an outbreak of systemic E. dermatitidis infection occurred in women who had received contaminated steroid injections at North Carolina hospitals.[15][16]

| Exophiala dermatitidis | |

|---|---|

| |

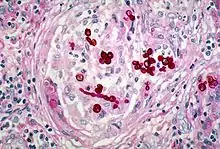

| histopathologic changes in phaeohyphomycosis due to Exophiala dermatitidis, formerly Wangiella dermatitidis using PAS stain | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Division: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | E. dermatitidis |

| Binomial name | |

| Exophiala dermatitidis (Kano) de Hoog (1977) | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

Appearance and general description

Exophiala dermatitidis forms slow growing, brown or black colonies.[11][12] As is common amongst black yeasts, E. dermatitidis is an anamorphic fungus with multiple conidial forms.[17][18][19] This morphological plasticity has complicated taxonomic determination based solely on physical appearance.[19] Young colonies are described as waxy,[11] mucoid,[17] smooth,[11][12] and yeastlike.[12][13] Over time pigmented aerial hyphae develop, and older colonies are described as appearing filamentous and velvety.[12][13][17][20] Conidia are between globular and elliptical in shape, and form at the mouth of short annellidic conidiogenous cells. Annellations can only be observed by electron microscopy.[12][13][17] Prior to analysis by scanning electron microscope, the conidiogenous cells were observed to form from non-annelated phialides and phialides without collarettes.[13] These observations caused the species to be erroneously provided with its own monotypic genus, Wangiella.[13] The species name Wangiella dermatitidis is still commonly used in the scientific literature.

The black fungus also takes on diverse morphologies in vivo. Infected tissues contain mixtures of ovoid yeast-like cells, short septate hyphae that may be branched or unbranched, toruloid hyphae, as well as isotopically enlarged sclerotic (muriform-like) cells that resemble those found in chromoblastomycosis.[21][22] The muriform-like cells isolated from E. dermatitidis infections have thinner walls than those found in chromoblastomycosis, and cells are divided along a single plane.[21]

A sexual form of E. dermatitidis has not been observed.[8] However, the occurrence of two mating type idiomorphs in approximately equal numbers among clinical and environmental isolates suggests that E. dermatitidis reproduces sexually.[23] Sequencing of rDNA has shown that clinical isolates of E. dermatitidis are very closely related to Capronia mansonii, and It has been predicted that the ascospores and ascomata of an E. dermatitidis teleomorph would therefore resemble those of C. mansonii.[8]

Ideal growth conditions for E. dermatitidis occur between 40 °C (104 °F) and 42 °C (108 °F),[11][13][24] however E. dermatitidis can tolerate temperatures as high as 47 °C (117 °F).[10] Metabolically active fungus is highly abundant in Turkish steam baths that routinely reach temperatures of over 60 °C (140 °F), but is typically not found in more hot and dry sauna facilities, or in cool environments surrounding steam baths.[24] It is thought that extracellular polysaccharides may protect the species from stress in hot and moist environments, as this feature is typical of strains isolated from steam baths.[9][24] Exophiala dermatitidis has carotenoid pigments in its cell wall that may serve a role in protecting E. dermatitidis from UV damage.[19]

Thermophilicity, negative potassium nitrate assimilation, negative melezitose assimilation, and an ability to decompose tyrosine are used to distinguish E. dermatitidis from other black yeasts.[11][12][19][20] An exoantigen test is useful in species determination, and DNA analysis can also be performed.[19] The fungus has been selectively isolated using high temperature incubation (at 40 °C) on media containing cycloheximide.[9]

Geographic distribution

Exophiala dermatitidis has been isolated around the world in low abundance from a variety of environmental sources, including soil, decaying timber, and wasp nests.[9][13][21] The thermophilicity and acid tolerance of E. dermatitidis suggests passage through warm-blooded animals, and it is hypothesized that its ecological niche might be associated with tropical, frugivorous bird and bat species.[14][25] An ability to utilize nutrients in diverse environments, to adhere to fruit surfaces, and progress through different morphological phases are considered to provide further evidence for this theory.[25] Clinical isolates tend to harbor strains that are found only rarely in nature.[14] It may be the case that traits linked to halotolerance have predisposed these strains towards infecting humans.[14]

While E. dermatitidis has been found only in low abundance in nature, the species is well suited to survive in a number of warm and wet man made niches. Metabolically active strains are isolated in high abundance from surfaces inside saunas, steam baths and humidifiers.[9][24] E. dermatitidis is one of the most common fungal species to inhabit dishwashers, and has been found in dishwashers around the world.[10]

Pathophysiology

Exophiala dermatitidis is typically considered a human opportunistic pathogen, as those affected by E. dermatitidis often have underlying health conditions.[11][12] An exception to this is the neurotropic clinical presentation, which is typically found in young and otherwise healthy individuals.[11]

While over 100 fungal species can cause phaeohyphomycosis, E. dermatitidis is one of the two fungi most frequently implicated, along with another Exophiala species, E. jeanselmei.[26][27] Exophiala dermatitidis is considered to be one of the most pathogenic fungi in the genus Exophiala,[14] and is highly deadly, with a fatality rate of over 40%.[19][28] The high fatality rate is primarily due to an ability to form systemic and neurotropic infections, which represent approximately half of reported E. dermatitidis cases.[19]

Local and superficial infections

Exophiala dermatitidis forms cutaneous and subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis, which most commonly affect the face and neck.[11][12][13][17][19][21] Indeed, the fungus was originally isolated from the skin of a patient with lesions on their cheek, neck, and ear.[19] Cells isolated from cutaneous infections are often spherical, and may form toruloid or moniliform chains.[19] Exophiala dermatitidis has been implicated various superficial infections including onychomycosis, otitis externa, and eye infections causing keratitis.[11][19][27]

In Europe E. dermatitidis tends to be associated with cystic fibrosis,[14] and is frequently found to have colonized the lungs of CF patients.[17] In one study, E. dermatitidis could be isolated from 6.2% of cystic fibrosis patients using erythritol-chloramphenicol agar culture dishes.[29] Exophiala dermatitidis has also been reported as the etiological agent of lung infections causing pneumonia.[11]

Systemic infections

Exophiala dermatitidis forms neurotrophic infections, and is the black yeast that most commonly causes life-threatening phaeohyphomycosis.[11][12][21] Conditions that might predispose people towards an invasive opportunistic infection include diabetes mellitus, lymphocytic leukemia, bronchiectasis, rheumatoid arthritis, and catheterization.[30] Systemic infections are often reported to be without cutaneous or subcutaneous involvement.[21]

Systemic E. dermatitidis infections can include cerebral metastases.[11][12] The fatality rate for such infections is reported to be over 90%.[28] Central nervous system phaeohyphomycosis is rare, and for unknown reasons primarily arise in East Asia, despite a cosmopolitan distribution of the fungus.[9] Within East Asian populations, young and otherwise healthy people have developed cerebral infections.[9] Lung infections in European CF patients and neurotropic mycosis in East Asia are caused by E. dermatitidis strains that are genetically similar, and host factors such as immunological differences may be responsible for the different infection patterns.[31] Exophiala dermatitidis occurs at very high frequency in both Asian and European saunas, and absence of neurotrophic mycosis in Europe isn't explained by reduced exposure to the fungus.[24]

In 2002 a small outbreak of systemic E. dermatitidis infection occurred in North Carolina hospitals, involving five women who received steroid injections for pain management.[15][16] In one of women the infection wasn't evident until 152 days after injection of the contaminated solution.[16] Isolates from these patients were found by the FDA to be susceptible to all of voriconazole, itraconazole, and amphotericin B. In one patient the infection caused sacroiliitis, while the remaining four developed meningitis.[16] Meningitis eventually caused death in one patient, while voriconazole was successful in treating infection in the four other patients.[16] The outbreak was traced back to a single compounding pharmacy, which was found by the FDA to have inadequately controlled for sterility of its products.[15][16]

Immune response

Exophiala dermatitidis typically causes a non-specific and granulomatous inflammatory response.[21] Lymphocytes, histiocytes, multinucleated giant cells and neutrophils are recruited.[21] The host responses are highly variable, often include cyst formation, and vary from weak reaction to an intense inflammatory response that results in tissue necrosis.[21]

As with other black yeasts that cause phaeohyphomycosis, melanin appears to have defensive purpose, and helps protect E. dermatitidis from death within human neutrophils.[9][26] Pathogenic strains of E. dermatitidis contain five times more melanin than saprophytic E. dermatitidis, while melanin deficient mutants of pathogenic strains have dramatically reduced virulence.[19]

Treatment

A diagnosis of E. dermatitidis infection of the CNS can only be reliably achieved following biopsy.[21] For systemic infections there are few treatment options, and E. dermatitidis is described as "notoriously resistant" to antifungal drugs.[19][21] During the North Carolina outbreak, treatment with voriconazole was effective in four out of the five patients, and all of voriconazole, itraconazole, and amphotericin B were found to be effective in vitro.[16] Terbinafine has also been found to be effective in vitro, and combinations of antifungal drugs can have a synergistic effect against E. dermatitidis.[32] A 2012 article found that of reported cases, 44% of patients responded to amphotericin B treatment, 50% responded to voriconazole treatment, and 71.4% responded to itraconazole therapy.[28]

For small and local infections surgery may be an option.[19] As E. dermatitidis infections are believed to be caused by traumatic implantation of the fungus, surgeons must be exceedingly careful to not re-introduce infection during operation.[19] Despite the high heat tolerance of E. dermatitidis, heat treatment of cutaneous lesions have been effective.[19]

References

- "Exophiala dermatitidis (Kano) de Hoog 1977". MycoBank. International Mycological Association. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- Kano K. (1934). "A new pathogenic Hormiscium Kunze causing chromoblastomycosis". Aichi Igakkai Zasshi (in Japanese). 41: 1657–73.

- Carrión AL. (1950). "Yeastlike dematiaceous fungi infecting the human skin: Special reference to so-called Hormiscium dermatitidis". Archives of Dermatology and Syphilology. 61 (6): 996–1009. doi:10.1001/archderm.1950.01530130114017. PMID 15419816.

- Conant NF, Smith DT, Baker RD, Callaway JL, Martin DS (1954). Manual of Clinical Mycology (2 ed.). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: WB Saunders. p. 276.

- Emmons CW, Binford CH, Utz JP (1963). "Medical Mycology". London, UK: Henry Kimpton: 291.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Schol-Schwarz, Marie Beatrice (1968). "Rhinocladiella, its synonym Fonsecaea and its relation to Phialophora". Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 34 (2): 119–152. doi:10.1007/BF02046424. PMID 5301320. S2CID 43876060.

- McGinnis MR. (1977). "Wangiella dermatitidis, a correction". Mycotaxon. 6 (2): 367–9.

- Untereiner, Wendy A.; Naveau, Francoise A. (1999). "Molecular Systematics of the Herpotrichiellaceae with an Assessment of the Phylogenetic Positions of Exophiala dermatitidis and Phialophora americana". Mycologia. 91 (1): 67–83. doi:10.2307/3761194. JSTOR 3761194.

- Reiss E, Shadomy HJ (2011). Fundamentals of Medical Mycology. John Wiley & Sons. p. 500. ISBN 978-0-470-17791-4.

- Zalar, P.; Novak, M.; de Hoog, G.S.; Gunde-Cimerman, N. (2011). "Dishwashers – A man-made ecological niche accommodating human opportunistic fungal pathogens". Fungal Biology. 115 (10): 997–1007. doi:10.1016/j.funbio.2011.04.007. PMID 21944212.

- de Hoog, G. S.; Guarro, J.; Gené, J.; Figueras, M. J. (2000). Atlas of clinical fungi (2. ed.). Utrecht: Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures [u.a.] ISBN 90-70351-43-9.

- Howard, Dexter H. (2003). Pathogenic fungi in humans and animals (2nd ed.). New York: Marcel Dekker. ISBN 0203909100.

- Kwon-Chung, K.J.; Bennett, John E. (1992). Medical mycology. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger. ISBN 0-8121-1463-9.

- Gunde-Cimerman, Nina; Plemenitaš, Ana; Oren, Aharon (2005). Adaptation to life at high salt concentrations in archaea, bacteria, and eukarya. Dordrecht: Springer. pp. 384–388. ISBN 1402036329.

- Richardson, Malcolm; Warnock, David W. (2010). Fungal infection : diagnosis and management (4th ed.). Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 387. ISBN 978-1405170567. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (13 December 2002). "Exophiala infection from contaminated injectable steroids prepared by a compounding pharmacy – United States, July–November 2002". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 51 (49): 1109–12. PMID 12530707. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

- Anaissie, Elias J.; McGinnis, Michael R.; Pfaller, Michael A. (2009). Clinical Mycology (2nd ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. p. 334. ISBN 978-1416056805. Retrieved 11 October 2014.

- Georgiev, Vassil St. (1998). Infectious diseases in immunocompromised hosts. Boca Raton: CRC Press. p. 909. ISBN 0849385539. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- Matsumoto, T; Matsuda, T; McGinnis, MR; Ajello, L (1993). "Clinical and mycological spectra of Wangiella dermatitidis infections". Mycoses. 36 (5–6): 145–55. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0507.1993.tb00743.x. PMID 8264710. S2CID 27029853.

- Tille, Patricia (2013). Bailey & Scott's Diagnostic Microbiology. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 766.

- Matsumoto, T.; Ajello, L.; Matsuda, T.; Szaniszlo, P.J.; Walsh, T.J. (1994). "Developments in hyalohyphomycosis and phaeohyphomycosis". Medical Mycology. 32 (s1): 329–349. doi:10.1080/02681219480000951. PMID 7722796.

- "Wangiella (Exophiala) dermatitidis". Broad Institute. Retrieved 12 November 2014.

- Metin B, Döğen A, Yıldırım E, de Hoog GS, Heitman J, Ilkit M. Mating type (MAT) locus and possible sexuality of the opportunistic pathogen Exophiala dermatitidis. Fungal Genet Biol. 2019 Mar;124:29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2018.12.011. Epub 2019 Jan 3. PMID 30611834

- Matos, T.; de Hoog, G. S.; de Boer, A. G.; de Crom, I.; Haase, G. (November 2002). "High prevalence of the neurotrope and related oligotrophic black yeasts in sauna facilities". Mycoses. 45 (9–10): 373–377. doi:10.1046/j.1439-0507.2002.00779.x. PMID 12421284. S2CID 4842988.

- Sudhadham, M.; Prakitsin, S.; Sivichai, S.; Chaiyarat, R.; Dorrestein, G.M; Menken, S.B.J.; de Hoog, G.S. (2008). "The neurotropic black yeast Exophiala dermatitidis has a possible origin in the tropical rain forest". Studies in Mycology. 61: 145–155. doi:10.3114/sim.2008.61.15. PMC 2610309. PMID 19287537.

- Johnson, Malcolm D.; Richardson, Elizabeth M. (2006). The pocket guide to fungal infection (2nd ed.). Malden, Mass.: Blackwell Pub. pp. 134–138. ISBN 9780470757734.

- Domer, J. E. (2004). Human fungal pathogens : with 31 tables (2nd ed.). Berlin [u.a.]: Springer. pp. 78–79. ISBN 9783540426295. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

- Patel, Atul K.; Patel, Ketan K.; Darji, Prakash; Singh, Rachna; Shivaprakash, M. R.; Chakrabarti, Arunaloke (May 2013). "endocarditis on native aortic valve in a postrenal transplant patient and review of literature on infections". Mycoses. 56 (3): 365–372. doi:10.1111/myc.12009. PMID 23013169. S2CID 40764387.

- Horré, R.; Schaal, K.P.; Siekmeier, R.; Sterzik, B.; de Hoog, G.S.; Schnitzler, N. (2004). "Isolation of Fungi, Especially Exophiala dermatitidis, in Patients Suffering from Cystic Fibrosis". Respiration. 71 (4): 360–366. doi:10.1159/000079640. PMID 15316209. S2CID 4832528.

- Szaniszlo PJ. (2002). "Molecular genetic studies of the model dematiaceous pathogen Wangiella dermatitidis". International Journal of Medical Microbiology. 292 (5–6): 381–90. doi:10.1078/1438-4221-00221. PMID 12452284.

- Uijthof, J. M. J.; Hoog, G. S.; Cock, A. W. A. M.; Takeo, K.; Nishimura, K. (24 April 2009). "Pathogenicity of strains of the black yeast Exophiala (Wangiella) dermatitidis: an evaluation based on polymerase chain reaction". Mycoses. 37 (7–8): 235–242. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0507.1994.tb00419.x. PMID 7739652. S2CID 20385551.

- Acton, Ashton Q. (2012). Azole Antifungals—Advances in Research and Application: 2012 Edition: ScholarlyBrief. ScholarlyEditions. pp. 14–15. ISBN 978-1481612265. Retrieved 9 November 2014.