Eystein I of Norway

Eystein Magnusson (Old Norse: Eysteinn Magnússon, Norwegian: Øystein Magnusson; c. 1088 – 29 August 1123) was King of Norway (as Eystein I) from 1103 to 1123 together with his brothers Sigurd the Crusader and Olaf Magnusson, although since Olaf died before adulthood, only Eystein and Sigurd were effective rulers of the country.

| Eystein Magnusson | |

|---|---|

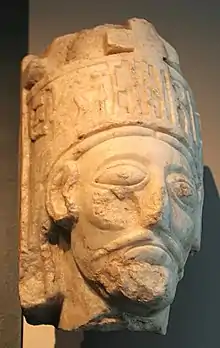

Early 12th century marble bust of Eystein. | |

| King of Norway | |

| Reign | 1103 – 29 August 1123 |

| Predecessor | Magnus III |

| Successor | Sigurd I |

| Co-rulers | Sigurd I, Olaf Magnusson |

| Born | c. 1088 |

| Died | 29 August 1123 (aged 33–35) Hustad, Romsdal, Norway |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | Ingebjørg Guttormsdatter |

| Issue | Maria Øysteinsdatter |

| House | Hardrada |

| Father | Magnus III of Norway |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

While Sigurd gained fame as the "warrior king" (although owed almost exclusively to his three-year crusade to the Holy Land), Eystein was in contrast portrayed in the sagas as the "peace king" who stayed home in Norway and improved the country. As Eystein never engaged in warfare, considerably less information is written and known about him than about his brother Sigurd, despite his twenty-year-long reign, just a few years short of Sigurd. Eystein nonetheless gained the affection of his people, and was highly regarded by the saga writers for his deeds. Eystein and Sigurd's reign became the longest joint rule in Norwegian history.

Although the later saga literature narrates stereotypical accounts about the two kings, Eystein is known to have improved the infrastructure and raised buildings and churches, particularly across the coast in Western Norway and Trøndelag, from Bergen to the fishing centre of Lofoten in the north. Eystein's activities were especially centered in Bergen, which became an important international trade hub for fish at the time, helped by his construction projects. His activities in Bergen included moving the royal seat to a more central location in the city and building a new royal palace, as well as constructing churches and the Munkeliv Abbey.

Eystein died of illness in August 1123, and his brother Sigurd thereby became the sole Norwegian king.

Background

Eystein was born in 1088 or 1089[1] as the first son of the future king Magnus Barefoot, born to an otherwise unknown mother who is only recorded to have been of "low birth". Upon the death of his father in 1103 during one of his campaigns in Ireland, Eystein became king together with his two brothers Olaf and Sigurd.[2] Sigurd was about a year younger than Eystein, while Olaf was more than ten years younger than him.[2] Sigurd was the only son who had accompanied their father Magnus on his campaign in the West, but he returned to Norway after Magnus' death.[3]

Many accounts concerning Eystein in later sagas are characterized by literary motifs, and have little value as sources on his life. Snorri Sturluson, the Icelandic author of the early 13th century Heimskringla mastered this literary style particularly well, stylistically and psychologically. His stories includes a so-called mannjevning (literally "comparison of men") between Eystein and Sigurd, in which the two boast about their skills and deeds in an attempt to outdo each other.[2] In a similar fashion, Snorri also tells a story about how Eystein managed to cure the melancholy of a friend, by agreeing to regularly clear time to talk with him about what troubled him.[4] On his physical appearance, Snorri wrote that Eystein "was the handsomest man that could be seen. He had blue open eyes; his hair yellow and curling; his stature not tall, but of the middle size."[5] More reliable information, particularly about Eystein's building-projects, is offered in earlier sagas such as the work of Theodoric the Monk, a Norwegian chronicler who wrote in the late 12th century.[2]

Reign

The co-rule between Eystein, Sigurd and Olaf entailed a shared kingship, and the kingdom itself was not divided into fixed borders. During the early years of their reign, Eystein is nonetheless said to have stayed mostly in Western Norway and Trøndelag, while Sigurd was in Viken. In practice, only Eystein and Sigurd ever ruled as kings, as Olaf was considerably younger and died when he was only seventeen years old, and virtually nothing is known about him beyond his name. One of the earliest acts by the kings was passing a retterbot, a special law ordained by the king, which among other things abolished various royal taxes that originated from the Danish rule of Sweyn Knutsson and Ælfgifu (under Cnut the Great) in the early 1030s. The kings became very popular because of this.[2] According to some sources, the main motivation for abolishing the taxes was to gain the support of the population for Sigurd's planned crusade.[3]

In 1107[1] or 1108,[3] after years of preparations, Sigurd sailed with a large fleet on a crusade to the Holy Land, the first European king ever to do so. Sigurd arrived back in Norway in 1111.[3] Eystein, on the other hand, did not engage in any warfare, and considerably less information is thus written about him than about Sigurd, although Snorri notes that he "had also effected much in the country that was useful while King Sigurd was on his journey."[6] While Sigurd gained fame in posterity as the "warrior king", although mainly because of his one-time crusade,[7] Eystein was portrayed by the saga writers as the "peace king" who stayed at home and improved the country.[2] Since Sigurd remained king for nineteen years after his crusade with little controversy, historian Claus Krag has considered that the domestic peace probably could be attributed equally to Sigurd.[8] In order to contrast Eystein with Sigurd, Snorri tells a story that Eystein instead subdued Jämtland to the Norwegian crown peacefully through the use of gifts and diplomacy. Despite Snorri's account, historical records indicate that Jämtland did not succumb to Norwegian rule until much later, during the reign of King Sverre in 1178.[2] Eystein and Sigurd are, however, known to have claimed monopoly on the trade and taxation in Finnmarken.[9]

Fish became an increasingly important commodity during Eystein's reign, as more cod was fished in Northern Norway and the demand for stockfish soared in Europe.[10] As the most suitable port, Bergen became the main trade hub for exporting stockfish, including trade connections with Grimsby in England,[2] while it also served to import much needed goods such as grain and flour.[10] To further the trade, Eystein had fishing booths and a church built in the fishing centre at Vågan in Lofoten in Northern Norway,[11] and he sailed north to Lofoten and Trondenes himself in 1114.[12] He also secured the route along the coast by constructing a port in Agdenes on the mouth of the Trondheimsfjord,[2] as well as smaller beacons along the coast.[10][11] Eystein's port construction in Agdenes was compared by Theodoric the Monk to that of Augustus Caesar at Brundisium,[13] an association readily reflected by Theodoric's use of the Latinised name form "Augustinus" for Eystein.[14] (Otherwise, Pope Callixtus II calls Eystein "Aistano" in a letter.)[15] The existence of a now lost port in Agdenes dated to around Eystein's reign has been supported by recent archaeological surveys in the area.[2] Snorri also says that Eystein had several large dry-docks built in Nidaros, and that he had a large ship built which "in size and shape" resembled the great ship Ormen Lange once built by King Olaf Tryggvason.[16] Eystein also improved the shelters in the mountain passes, notably at Hjerkinn in Dovre, to more comfortable houses with permanent supervision.[11]

In Snorri's mannjevning between Eystein and Sigurd, Eystein allegedly maintains that his own building-projects in Norway were "more useful for the country," than "you [Sigurd] killing bluemen for the devil in Serkland."[2] Eystein was particularly active in Bergen, and his role in the development of the city was probably more important than that of King Olaf Kyrre, the founder of the city according to the sagas.[17] He moved the royal seat in the city from Alrekstad to Holmen on the eastern shore of Vågen, in the city core, thereby rationalising the bureaucracy.[10] At Holmen, he built a Church of the Apostles (probably a stave church)[18] and a St. Nicholas Church,[10] as well as a royal palace which according to Snorri Sturluson was the most imposing wooden building ever raised in Norway[2] (although Theodoric the Monk who wrote earlier already noted it was "now almost collapsed from excessive age").[13] He also built a St. Michael's Church and founded the Benedictine abbey Munkeliv Abbey at Nordnes,[10] and the tithe to the church was introduced during the reign of Eystein and Sigurd.[3]

Eystein died on 29 August 1123, not long after he was "seized with an illness" during a feast at Hustad in Fræna, Møre og Romsdal.[2] Snorri tells that his body thereafter was taken to Nidaros, and buried in the Nidaros Cathedral. According to Snorri, it was "generally said that so many mourners never stood over any man's grave in Norway as over King Eystein's," at least since the death of Magnus the Good.[16] The reign of Eystein and Sigurd was the longest joint rule in Norwegian history.[1] Sigurd ruled alone after Eystein's death, until Sigurd's own death in 1130.[2]

Family

Eystein married Ingebjørg Guttormsdatter, from a prominent noble family of Gudbrandsdalen. Their marriage was part of Eystein's strategy of building alliances in Eastern Norway. They had a daughter, Maria, who became the mother of the future royal pretender Olaf Ugjæva by her marriage to the lendmann Gudbrand Skavhoggsson. Olaf was named king in 1165, during the Norwegian civil war era, but was subsequently defeated by Magnus Erlingsson and forced to flee the country.[19]

Legacy

Opinions on Eystein have been strongly favourable. Theodoric the Monk wrote about Eystein that he "was a paragon of honesty who governed himself no less than his subjects with moderation and wisdom. He was a king who loved peace, an assiduous manager of public affairs, and above all a fosterer of the Christian religion."[13] Snorri Sturluson later wrote that Eystein "was wise, intelligent, and acquainted with the laws and history. He had much knowledge of mankind, was quick in counsel, prudent in words, and very eloquent and very generous. He was very merry, yet modest; and was liked and beloved, indeed, by all the people."[5] The view of Eystein as a peaceful and domestically active king has been supported by modern historians such as Claus Krag, although noting that the literary embellishments should be disregarded.[2]

A stylized marble bust of Eystein, dated to before the middle of the 12th century,[2] was found during excavations at Munkeliv Abbey in 1853, and it represents the oldest known preserved portrait of a Norwegian king.[20] The bust has the inscription "EYSTEIN REX", and was originally probably part of a full figure statue built into the wall.[21] The headpiece worn on the bust has been said to resemble a German Imperial crown,[22] or to be of a Byzantine type.[21] According to Snorri Sturluson, Eystein had "somewhat large eyes", which seems to correspond with the bust. Since Snorri may have seen the bust in Bergen himself, it is unclear if his account represents an independent source on Eystein's physical appearance.[20] Today, the bust is located in the collections of Bergen Museum.[2]

To commemorate his status as founder of the fishing town Vågan (although it had been an important centre for at least a century), a huge statue of Eystein (Øysteinstatuen) by Arthur Gustavson was raised at Breidablikk in Vågan in 1935,[23] after an idea of architect Harald Sund.[24] At Hjerkinn in Dovre, a church dedicated to Eystein (Eysteinskyrkja) was constructed in 1969 according to a design by Magnus Poulsson, in commemoration of Eystein's construction of a sælehus or shelter near the village.[25]

References

- "Eystein I Magnusson". Britannica. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- Krag, Claus. "Øystein 1 Magnusson". Norsk biografisk leksikon (in Norwegian). Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- Krag, Claus. "Sigurd 1 Magnusson Jorsalfare". Norsk biografisk leksikon (in Norwegian). Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- Saga of Sigurd the Crusader and his brothers Eystein and Olaf, chapter 18.

- Saga of Sigurd the Crusader and his brothers Eystein and Olaf, chapter 17.

- Saga of Sigurd the Crusader and his brothers Eystein and Olaf, chapter 15.

- Krag (1995) p. 175

- Krag (1995) p. 177

- Gunnes (1976) p. 345

- Hartvedt (1998) p. 7

- Gunnes (1976) p. 313

- Bertelsen (1995) p. 18

- The Ancient History of the Norwegian Kings, chapter 32.

- The Ancient History of the Norwegian Kings, chapter 32, footnote 316.

- Storm, Gustav; Huidtfeldt-Kaas, H. J.; Bugge, Alexander (eds.). Nummer: 2. Dato: [1119.] Sted: [Rom.] (in Norwegian and Latin). Vol. XVII. Diplomatarium Norvegicum. p. 2.

- Saga of Sigurd the Crusader and his brothers Eystein and Olaf, chapter 27.

- Gunnes (1976) p. 331

- Lidén (1980) p. 137

- Bratberg, Terje. "Ingebjørg Guttormsdatter". Norsk biografisk leksikon (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 7 October 2012. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- Krag (1995) p. 176

- Lidén (1980) p. 150

- Gunnes (1976) p. 340

- Bertelsen (1995) pp. 18-19

- "Kong Øystein". Kabelvågavisa (in Norwegian). 15 March 2009. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- Lunde (1997) p. 44

Bibliography

- Primary sources

- Sturluson, Snorri (c. 1230). Saga of Sigurd the Crusader and his brothers Eystein and Olaf (in Heimskringla). English translation: Samuel Laing (London, 1844).

- Theodoric the Monk (c. 1180). The Ancient History of the Norwegian Kings. English translation: David and Ian McDougall (London, 1998).

- "Retterbot fra kongene Sigurd, Øystein og Olav Magnussønner" [1103 - 1107], summary in Norwegian. Regesta Norvegica.

- Modern literature

- Bertelsen, Reidar (1995). Vágar: den første byen i nord (in Norwegian). Nordland fylkeskommune.

- Gunnes, Erik (1976). Rikssamling og kristning 800-1177. Norges historie (in Norwegian). Vol. 2. Cappelen.

- Hartvedt, Gunnar Hagen (1998). Bergen mellom smil og tårer: lokalhistorisk håndbok og fredningsoversikt (in Norwegian). Dreggen forlag.

- Krag, Claus (1995). Vikingtid og rikssamling 800-1130. Aschehougs norgeshistorie: 800-1130 (in Norwegian). Vol. 2. Aschehoug.

- Lidén, Hans-Emil (1980). Bergen. Norges kirker (in Norwegian). Vol. 1. Land og kirke.

- Lunde, Jon Vegard (1997). Kulturhistorisk vandrebok: pilegrim gjennom Dovre (in Norwegian Nynorsk). Komiteen for pilegrimsleden gjennom Dovre.

External links

- Linklater, Alexander (23 December 2006). "The king who listened". The Guardian. (retelling of Ívars þáttr Ingimundarsonar).