Es'kia Mphahlele

Es'kia Mphahlele (17 December 1919 – 27 October 2008) was a South African writer, educationist, artist and activist celebrated as the Father of African Humanism and one of the founding figures of modern African literature.

Es'kia Mphahlele | |

|---|---|

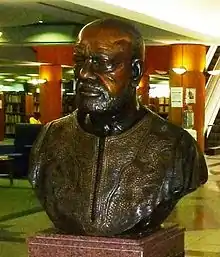

His bust in the Es'kia Mphahlele Community Library, Pretoria | |

| Born | Ezekiel Mphahlele 17 December 1919 Marabastad, Pretoria, Union of South Africa |

| Died | 27 October 2008 (aged 88) Lebowakgomo, Limpopo, South Africa |

| Occupation | Writer, educationist, philosopher |

| Language | SePedi, SeTswana, SeSotho, IsiZulu, English, Afrikaans |

| Genre | Drama, fiction, poetry, |

He was given the name Ezekiel Mphahlele at birth but changed his name to Es'kia in 1977. His journey from a childhood in the slums of Pretoria to a literary icon was an odyssey both intellectually and politically. As a writer, he brought his own experiences in and outside South Africa to bear on his short stories, fiction, autobiography and history, developing the concept of African humanism. He skilfully evoked the black experience under apartheid in Down Second Avenue (1959). It recounted his struggle to get an education and the setbacks he experienced in his teaching career.[1][2]

Mphahlele wrote two autobiographies, more than 30 short stories, two verse plays and a number of poems. He is deemed as the "Dean of African Letters".[3]

He was the recipient of numerous international awards. In 1984, he was awarded the Order of the Palm by the French government for his contribution to French Language and Culture. He was the recipient of the 1998 World Economic Forum Crystal Award for Outstanding Service to the Arts and Education. In 1998, former President Nelson Mandela awarded Mphahlele the Order of the Southern Cross, then the highest recognition granted by the South African Government (equivalent today to the Order of Mapungubwe).[4]

Biography

Family life

Es'kia Mphahlele was born in Pretoria, in the Union of South Africa, in 1919. From the age of five, he lived with his paternal grandmother in Maupaneng Village, in GaMphahlele (Now in Lepelle-Nkumpi Municipality) Limpopo Province, where he herded cattle and goats. His mother, Eva, took him and his two siblings to go live with her in Marabastad (2nd Avenue) when he was 12 years old.

He married Rebecca Nnana Mochedibane, whose family was a victim of forced removals in Vrededorp, in 1945 (the same year his mother died). A qualified social worker with a diploma from Jan Hofmeyer School, in Johannesburg, she and Mphahlele would have five children. When he went into exile from South Africa, he left behind his entire extended family, except for his wife and children, going for years without seeing them. While in Nigeria, he once tried taking advantage of a British passport before Nigerian independence. He applied for a visa through the consulate in Nairobi, in order to visit his younger brother Bassie (Solomon) who was ill with throat cancer, but his application was turned down.

Rebecca Nnana Mochedibane (Mphahlele)

Rebecca was born in Sophiatown. She first qualified as a teacher before pursuing a social work diploma. She remembered meeting Zeke, and being very impressed by him: "The other young men were not readers and I could not relate to them. They could not relate to the outside world through literature." The couple met when Mphahlele was working at the Blind Institute, in Roodepoort. A group of teacher students had come to visit the institute where they read books to the elderly. Es'kia was impressed and requested to visit Rebecca in her hometown during the holidays. It was Rebecca's final year at the training college. The couple decided on 29 August 1945 as their wedding date. Mphahlele's mother had fallen sick, and died at the age of 45, just before the couple got married.

"For her part, Rebecca, always busy with the kids, survived by her own ingenuity and native practical sense, by her outgoing temperament. She has always been able to bulldoze into a new community, let people know what her intentions are, openly tell them what she likes and what she doesn't, without being either rude or patronising" –Es'kia Mphahlele.

In Kenya, she worked as a social worker in the U.N. Freedom From Hunger Campaign, in charge of their educational programme.

She read for her MA in Social Work at the University of Denver.

As a student

At the age of 15, Mphahlele began attending school regularly and enrolled at St Peters Secondary School, in Rosettenville (Johannesburg). He finished high school by private study. That became his learning method until his PhD qualification. He obtained a First-Class Pass (Junior Certificate). He received his Joint Matriculation Board Certificate from the University of South Africa in 1943. While teaching at Orlando High School, Mphahlele obtained his B.A. in 1949 from the University of South Africa, majoring in English, Psychology and African Administration. In 1955, he received his Honours degree in English from the same institution. While working at Drum magazine, Mphahlele made history by becoming the first person to graduate M.A. with distinction at UNISA, in 1957. His thesis was entitled "The Non-European Character in South African English Fiction".

From 1966 to 1968, under the sponsorship of the Farfield Foundation, Mphahlele became a Teaching Fellow in the Department of English at the University of Denver, Colorado, where he earned his PhD in Creative Writing. In lieu of a thesis, he wrote a novel entitled The Wanderers. He was subsequently awarded First Prize for the best African novel (1968–69) by African Arts magazine at the University of California, Los Angeles.

| Year | Qualification | Institution | Honours |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1968 | PhD., Creative Writing | University of Denver, Colorado | Awarded First Prize for the best African novel from 1968 to 1969 by African Arts magazine, University of California, Los Angeles |

| 1957 | M.A. English (with distinction). Thesis: "The Non-European Character in South African English Fiction" | University of South Africa (UNISA) | First person to graduate M.A. English with distinction at UNISA |

| 1955 | B.A. (Honours) | UNISA | |

| 1949 | B.A., majoring in English, Psychology and African Administration | UNISA | |

| 1943 | Joint Matriculation Board Certificate | UNISA | |

| 1940 | Teacher's Certificate | Adams College, Natal |

As an educator

Mphahlele obtained his Teacher's Certificate at Adams College in 1940. He served at Ezenzeleni Blind Institute as a teacher and a shorthand-typist from 1941 to 1945. He and his wife moved their family to Orlando East, near the historic Orlando High School, in Soweto as he joined the school in 1945 as an English and Afrikaans teacher. There, in the company of many freshly-minted from Fort Hare young teachers, he became active in the Transvaal African Teachers' Association (TATA). The 1949 Eislen Commission on Native Education, inspired by Dr. Hendrik Verwoerd, the recently elected National Party's Minister of Native Affairs, had recommended a radically new system of Education for Africans. TATA, together with other teachers' organisations in the Cape, the Free State and Natal, took up the cudgels to oppose it. For his participation in that agitation, in December 1952 Mphahlele, Isaac Matlare and Zephania Mothopeng were dismissed from their posts.[5] Mphahlele's protest against the introduction of Bantu Education resulted in his teaching career being cut short.

He was banned from teaching anywhere in South Africa by the apartheid government. He left South Africa and went into exile. His first stop was Nigeria, where he taught in a high school for 15 months, then at the University of Ibadan, in their extension programme. He also worked at the C.M.S. Grammar School, in Lagos. He worked in the Department of Extra-Mural Studies at the University of Ibadan, travelling to various outlying districts to teach adults. While based in Paris, he became a visiting lecturer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He also lectured in Sweden, France, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Sierra Leone, Ghana, Senegal and Nigeria. Mphahlele believed that alternative education can pave the way for a transformative and humane educational system for all.[6]

Nigeria (1957–61)

Mphahlele spent 20 years in exile, of which he spent four years in Nigeria with his family. He wrote: "It was a fruitful experience. The people of Nigeria were generous. The condition of being an outsider was not burdensome. I had time to write and engage in the arts." He was working with the best in Nigerian; playwright, poet and novelist Wole Soyinka; poets Gabriel Okara and Mabel Segun; novelist Amos Tutuola; sculptor Ben Enwonwu; and painters Demas Nwoko and Uche Okeke, and so on. His visits to Ghana became frequent as each trip added more literary giants to his list of networks and colleagues. The University of Ghana would invite him to conduct extramural writers' workshops. That is where he met Kofi Awoonor (then George Awoonor Williams), playwright Efua Sutherland, poet Frank Kobina Parkes, musicologist Professor Kwabena Nketia, historian Dr J. B. Danquah, poet G. Adali-Mortty and sculptor Vincent Kofi.

Mphahlele attended the first All-African Peoples' Conference organised by Kwame Nkrumah in Accra, Ghana, in December 1958. "Ghana was the only African country that had been freed from the European colonialism that had swept over the continent in the 19th century. Most of the countries represented at Accra were still colonies."[7] Mphahlele recalls meeting with the late Patrick Duncan and Jordan Ngubane, who were representing the South African liberal view. It was at this conference that Mphahlele met Kenneth Kaunda, and listened to Frantz Fanon deliver a fiery speech against colonialism. Rebecca, his wife, returned to South Africa towards the end of 1959, to give birth to their last-born, Chabi. They returned in February 1960. They were in Nigeria when they heard about the Sharpeville Massacre. Mphahlele said: "Yes, Nigeria and Ghana gave Afrika back to me. We had just celebrated Ghana’s independence, and were three years away from Nigeria's."

France (1961–63)

Mphahlele moved his family to France in August 1961, their second major move. He was appointed as the Director of the African Program of The Congress for Cultural Freedom and went to Paris. They lived on Boulevard du Montparnasse, just off St. Michel, a few blocks from the Le Select and La Coupole restaurants. Their apartment was soon to become a kind of crossroads for writers and artists: Ethiopian artist Skunder Boghossian; Wole Soyinka; Gambian poet Lenrie Peters; South African poet in exile Mazisi Kunene; Ghanaian poet and his beloved friend J. P. Clark; and Gerard Sekoto. It was during his stay in France when Mphahlele was invited by Ulli Beier and other Nigerian writers to help form the Mbari Writers and Artists Club in Ibadan. They raised money from Merrill Foundation in New York to finance Mbari Publications, a venture the club had undertaken. Work by Wole Soyinka, Lenrie Peters and others was first published by Mbari Publishers before finding its way to commercial houses. He edited and contributed to Black Orpheus, the Ibadan-based literary journal. He toured and worked in major African cities including Kampala, Brazzaville, Yaoundé, Accra, Abidjan, Freetown and Dakar. He also attended seminars connected with work in Sweden, Denmark, Finland, West Germany, Italy, and the US.

Mphahlele went on to set up an Mbari Centre in Enugu, Nigeria, under the directorship of John Enekwe. In 1962, at Makerere University, in Kampala, Uganda, they organised the first African Writers Conference, attended also by fellow South Africans Bob Leshoai, who was on tour, and Neville Rubin, who was editing a journal of political comment in South Africa. Two conferences, one in Dakar and another in Freetown were organised in 1963. Their aim was to throw into open debate the place of African literature in the university curriculum. They wanted to drum support up for the inclusion of African literature as a substantive area of study at university, where traditionally it was being pushed into extramural departments and institutes of African Studies. Mphahlele had only planned to stay in Paris for two years, after which he would return to teaching. Those experiences had made him yearn for the classroom again.

Kenya (1963–66)

John Hunt, the executive director of the Congress for Cultural Freedom suggested that Mphahlele establish a centre like the Nigerian Mbari in Nairobi. Mphahlele arrived in Nairobi in August 1963, and December had been set for Kenya's independence. By the time Rebecca and the children arrived, he had already bought a house. Prior to that, he had been housed by Elimo Njau, a Tanzanian painter. Njau suggested a name everyone liked – Chemchemi, Kiswahili for "fountain". Within a few months, they had converted a warehouse into offices, a small auditorium for experimental theatre and intimate music performances, and an art gallery. Njau ran the art gallery on a voluntary basis. He mounted successful exhibitions of Ugandan artists Kyeyune and Msango, and of his own work. "My soul was in the job. I was in charge of writing and theatre" (Mphahlele, Africa My Music).

Their participants were from the townships and locations that were a colonial heritage. Mphahlele would travel to districts to outside districts to run writers' workshops in schools that invited him, accompanied by the centre's drama group. Their travelling was well captured in Busara, edited by Ngugi wa Thiong'o and Zuka, edited by Kariara. When the Alliance High School for Girls (just outside Nairobi) asked him to write a play for its annual drama festival, in the place of the routine Shakespeare Mphahlele adapted Grace Ogot's "The Rain Came", a short story, and called it Oganda’s Journey. "The most enchanting element in the play was the use of traditional musical idioms from a variety of ethnic groups on Kenya. A most refreshing performance, which exploited the girl’s natural and untutored acting," he said. After serving for two years, he felt he done what he had come for, as he had indicated before taking the job that he would not stay for more than two years. He turned down a lecturing post at the University College of Nairobi. They could only offer him a one-year contract, which he could not take.

Colorado, US (1966–74)

In May 1966 Mphahlele moved his family to Colorado, where he was joining the University of Denver's English Department. Mphahlele was granted a tuition waiver by the university for the course work he had to do before he could be admitted for the PhD dissertation. He paid for the Afrikan Literature and Freshman Composition himself.

Philadelphia (1974–77)

The Mphahlele family arrived in Philadelphia in May 1974. Mphahlele was about to begin a lecturing career at the University of Pennsylvania in September of that year. They had bought a house in Wayne, some 24 kilometres from Philadelphia, on the Western Mainline.

Mphahlele spent his time in Philadelphia teaching, writing and never stopped thinking about going back home to South Africa. He recalled how since their days in Denver, he and Rebecca had longed to be in Africa again, and it had to be South Africa. They felt anything else would just be an adventure. They longed for community, a cultural milieu in which their work could be relevant. They were considered to have become British nationals, and had to approach the South African government through a single person in authority, Dr. C. N. Phatudi, the then Chief Minister of Lebowa, who had agreed to make representations on their behalf. As their application was being processed, which took more than five years, his books were still being banned in South Africa.

As a novelist and short-story writer

It was during his primary school days when he started rooting everywhere for newsprint to read. He recalled always looking for any old scrap of paper to read. He further recalled a small one-room tin shack the then municipality called a "reading room", on the western edge of Marbastad. He remembered it being stacked with dilapidated books and journals, junked by some bored ladies in the suburbs. He dug out of the pile Miguel de Cervantes' Don Quixote, and went through the whole lot like a termite, elated by the sense of discovery, recognition of the printed word and by the mere practice of the skill of reading. Cervantes stood out in his mind, although his imagination was also fired by the silent movies of the 1930s. He enjoyed a combination of Cervantes' Don Quixote and Sancho Panza together with Laurel and Hardy and Buster Keaton. Mphahlele would read the subtitles aloud to his friends who could not read well, amid the yells and foot stamping and bouncing on chairs to the rhythm of the action.

The 1959 publication of his autobiographical novel Down Second Avenue drew worldwide interest in Mphahlele as a writer, and focused a powerful spotlight on the internal dynamics of South Africa as it steadily drifted toward greater racial oppression and greater world isolation. Now a classic of African literature, Down Second Avenue had successful printings in English, French, German, Russian, Dutch and Japanese, reflecting the impact and international popularity of the book. Mphahlele's second novel, The Wanderers, was a story chronicling the experience of exiles in Africa.[8]

While in Paris, Mphahlele published The Living and the Dead, in 1961. Six years later, in East Africa, he published In Corner B. The contents of both collections of short stories are included in The Unbroken Song (1986), which also contains some of his poems.

As part of his Master's thesis, in 1962 he published The African Image, which provides a historical perspective of South African literature.[9] In 1967, he edited the anthology African Writing Today, which was published by Penguin.[10] During his PhD, he produced The Wanderers, a novel of exile originally submitted as a dissertation for his PhD in creative writing.[9] Down Second Avenue was doing so well such that it was translated into French and German in 1964. In December 1978, the Minister of Justice took Mphahlele's name off the list of writers who may be quoted, and whose works may not be circulated in the country. Only Down Second Avenue, Voices in the Whirlwind and Modern African Stories, which he had co-edited, could then be read in the country. Other publications remained banned.

The first comprehensive collection of his critical writing was published under the title ES'KIA in 2002, the same year that the Es'kia Institute was founded. Mphahlele's life and work is currently found in the efforts of a non-governmental, non-profit organisation based in Johannesburg.

Return to South Africa

Mphahlele set foot on South African soil on 3 July 1976, at the Jan Smuts Airport (now O. R. Tambo International Airport). He had been invited by the Black Studies Institute in Johannesburg to read a paper at its inaugural conference. He recalled: "I was emerging on to the concourse when I was startled by a tremendous shout. And they were on top of me – some one hundred Africans, screaming and jostling to embrace me, kiss me. Relatives, friends and pressmen from my two home cities – Johannesburg and Pretoria. I was bounced hither and thither and would most probably not have noticed if an arm or legs were torn off of me, or my neck was being wrung. Such an overwhelming ecstasy of that reunion. The police had to come and disperse the crowd as it had now taken over the concourse."

Mphahlele returned to Philadelphia on 27 July 1976, after three stimulating weeks in South Africa. He and Rebecca wrote letter after letter, yearning to return home. Mphahlele believed there were armed with what was necessary to contribute towards building South Africa. He was certain that the social work and education knowledge and experience through their qualifications could be rewarding if they were part of a cultural matrix, and promoted the extension of culture, the growth of the people.

The Mphahleles officially returned to South Africa in 1977, on Rebecca's birthday (17 August). "When I came back, things were much worse. People were resisting what had become a more and more oppressive government. We came back at a dangerous time. It was a time when we knew we would not be alone, and that we would be among our people" (Mphahlele, 2002). Mphahlele waited for six months for the then University of the North to inform him whether he would get the post of English professor which was still vacant. The answer was "no". The government service of Lebowa offered him a job as an inspector of schools for English teaching. Rebecca had found a job as a social worker. In his autobiography Afrika My Music, he describes how the ten months of being an inspector were like. "I had the opportunity to of travelling the length and breadth of the territory visiting schools and demonstrating aspects of English teaching. I saw for myself the damage of Bantu Education had wrought in our schooling system over the last twenty-five years. Some teachers could not even express themselves fluently or correctly in front of a class, and others spelled words wrongly on the blackboard."

In 1979, he joined the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits University) as a senior research fellow at the African Studies Institute. He founded the Council for Black Education and Research, an independent project for alternative education involving young adults. He founded the department of African literature at Wits University in 1983, a significant event in the evolution of literature teaching in South Africa at the time.[11] He became the institution's first black professor. He was permitted to honour an invitation from the then Institute for Study of English in Africa at Rhodes University. It was a two-month research fellowship where his proposal of finishing his memoir Afrika My Music, which he had begun in Philadelphia, was accepted.

After his retirement from Wits University in 1987, Mphahlele was appointed as the executive chairman of the board of directors at Funda Centre for Community Education. He continued visiting other universities as a visiting professor teaching mostly African Literature. He spent two months at Harvard University's Graduate School of Education teaching a module on secondary-school education in South Africa. With the end of apartheid, he emerged as an eloquent proponent of the need to nurture the arts to feed a culture traumatized by colonization and oppression.[12] The Es'kia Institute is named after him, honouring his life, teachings and philosophies. His return home and contribution towards the development of the country and continent's literary development is still being celebrated in many forms, with some towns choosing to name significant streets after him.[13]

Bibliography

Publications

| Year | Title | Other Publications | Important Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1947 | Man Must Live and Other Stories, Cape Town: African Bookman | ||

| 1959 | Down Second Avenue (autobiography), London: Faber & Faber | Berlin: Seven Seas, 1962; New York: Doubleday, 1971 | It was translated into ten European languages, Japanese and Hebrew. It was also banned in South Africa under the Internal Security Act |

| 1962 | The African Image, London: Faber & Faber | New York: Praeger, 1964; revised edition Faber & Faber, 1974; Praeger, 1974 | It was banned in South Africa under the 1966 under the Internal Security Act |

| 1966 | A Guide to Creative Writing (pamphlet), East African Literature Bureau | ||

| 1967 | In Corner B & Other Stories | East African Publishing House, Nairobi | It was banned in South Africa from 1966 to 1978 under the Internal Security Act |

| 1971 | The Wanderers, New York: Macmillan Co. | London: Fontana/Collins (pb), 1973; David Phillip, 1984 | It was banned in South Africa under the Internal Security Act |

| 1971 | Voices in the Whirlwind and Other Essays, London: Macmillan | New York: Hill & Wang, 1972; London: Fontana/Collins (pb), 1973 | It was banned in South Africa under the Internal Security Act from 1971 to 1978 |

| 1980 | Chirundu, Johannesburg: Ravan Press | London: Thomas Nelson, 1980; New York: Lawrence Hill, 1981 | |

| 1981 | The Unbroken Song: Selected Writings (poems and short stories), Johannesburg: Ravan Press | ||

| 1981 | Let's Write a Novel: A Guide, Cape Town: Maskew Miller | ||

| 1984 | Afrika My Music (second autobiography), Johannesburg: Ravan Press | ||

| 1984 | Father Come Home (novel), Johannesburg: Ravan Press | ||

| 1987 | Let's Talk Writing:Prose (A guide for writers), Johannesburg: Skotaville Publishers | ||

| 1987 | Let's Talk Writing:Poetry (A guide for writers), Johannesburg: Skotaville Publishers | ||

| 1988 | Renewal Time (short stories), New York: Readers International | ||

| 2001 | Es'kia, Kwela Books with Stainbank & Associates | Shortlisted for the Sunday Times Alan Paton Award for Non-Fiction | |

| 2004 | Es'kia Continued, Johannesburg: Stainbank & Associates |

Selected papers

| Year | Title | Institution/Organisation |

|---|---|---|

| 1997, March | The Function of Literature at the Present Time | University of Fort Hare |

| 1992 | The Disinherited Imagination | University of Limpopo (then The University of the North) |

| 1991, April | Notes on African Value Systems in relation to Education and Development | Institute for African Alternatives, Johannesburg |

| 1991, Feb | The State of Well-being in Traditional Africa (Seminar Theme: Social Work and the Politics of Dispossession) | Council for Black Education and Research, Soweto |

| 1990, Nov | Educating the Imagination (in College English, Boston, MA) | National Council for Teachers of English Conference, Atlanta |

| 1990, May | Education as Community Development (Witwatersrand University Press, 1991) | Centre for Continuing Education, University of the Witwatersrand (Dennis Etheredge Commemoration Lecture) |

| 1990, March | From Interdependence towards Nation Building | University of Limpopo |

| 1987, May | The Role of Education in Society | Education Opportunities Council Conference, Johannesburg |

| 1984, June | Poetry and Humanism: Oral Beginnings | Institute for the Study of Man in Africa, University of the Witwatersrand (Raymond Dart Lecture: published as Lecture 22 of the Raymond Dart Lectures, Witwatersrand University Press) |

| 1984, May | The Crisis of Black Leadership | Funda Centre, Soweto |

| 1981, Feb | Philosophical Perspectives for a Programme of Educational Change | Council for Black Education and Research, Durban |

| 1980, June | Multicultural Imperatives in the Planning of Education for a future South Africa | Teachers' Association of South Africa, Durban (Asian) |

References

- Shola Adenekan, "Obituary: Es'kia Mphahlele", The Guardian, 24 November 2008.

- Alastair Niven, "Es'kia Mphahlele: Founding figure of modern African literature who became a powerful voice in the fight for racial equality", The Independent, 31 October 2008.

- "New book sings praises", Monday Paper archives, Volume 25.14, University of Cape Town, 12 June 2006.

- "Es'kia Mphahlele: 1919 – 2008", Books Live, 28 October 2008.

- "Dr. Es'kia Mphahlele", SA History Online.

- "Speeches". education.gov.za. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- Mphahlele, in Afrika My Music.

- James Ainsworth, "Es'kia Mphahlele's African Literary Journey", An Eye on Africa, 3 February 2006.

- "SA remembers Es'kia Mphahlele", Media Club South Africa, 30 October 2008.

- Vivian Bickford-Smith (2016). The Emergence of the South African Metropolis: Cities and Identities in the Twentieth Century. Cambridge University Press. p. 224. ISBN 9781107002937.

- Leon De Kock, "Leaving the forefront of African lit", Mail & Guardian, 1 November 2008.

- Donna Bryson, "South African writer Es'kia Mphahlele dies", USA Today, 30 October 2008.

- "Pretoria’s new street names".