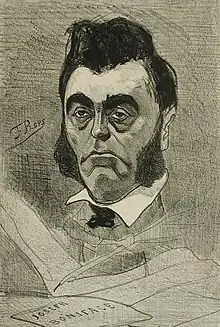

Félicien Rops

Félicien Victor Joseph Rops (7 July 1833 – 23 August 1898) was a Belgian artist associated with Symbolism and the Parisian Fin-de Siecle. He was a painter, illustrator, caricaturist and a prolific and innovative print maker, particularly in intaglio (etching and aquatint). Although not well known to the general public, Rops was greatly respected by his peers and actively pursued and celebrated as an illustrator by the publishers, authors, and poets of his time. He provided frontispieces and illustrations for Jules Barbey d'Aurevilly, Charles Baudelaire, Charles De Coster, Théophile Gautier, Joris-Karl Huysmans, Stéphane Mallarmé, Joséphin Péladan, Paul Verlaine, Voltaire, and many others. Best known today for his prints and drawings illustrating erotic and occult literature of the period, he also produced oil paintings including landscapes, seascapes, and occasional genre paintings. Rops is recognized as a pioneer of Belgian comics.[1]: 243 p. [2][3][4]: 3-5 p.

Félicien Rops | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 7 July 1833 Namur, Belgium |

| Died | 23 August 1898 (aged 65) |

| Nationality | Belgian |

| Known for | Print making, intaglio, illustrations, drawing, painting |

| Notable work | Pornocrates Les Sataniques Les Diaboliques |

| Movement | Symbolism, Decadent movement, Fin de siècle |

Biography

Childhood and education (1833–1857)

Rops was born 7 July 1833 in Namur, Belgium, the only child of Sophie Maubile and Nicholas Rops. The Rops were a well-off bourgeois family, their wealth coming from textile manufacturing. Félicien was educated at his home by private tutors until the age of ten; then in 1843, he enrolled in a local Jesuit school for the next five years. His ability to recite lengthy passages from the Bible in Latin attest to both a good education and his intelligence, although even as a schoolboy it is reported that he had "begun to let fantasy dominate his thinking" and received complaints about "his passion for producing uninhibited caricatures of his teachers".[5]: 8 p. Nicholas Rops died in 1849. After some disagreements between Rops and his mother over the direction of his future education, a compromise was reached, and in June 1849 he enrolled at the Athénée secondary school in Namur while simultaneously attending the Academy of Fine Arts there.[2][4]: 22 p. [5]: 8 p. [6]

In 1851, Rops moved to Brussels and began studying law at the University of Brussels. However, by 1853, he was attending the Académie de Saint-Luc where he studied drawing and developed his skill as a draughtsman working from live models, meeting others like Louis Artan, Constantin Meunier, and Charles de Groux, and taking part in the local Bohemian milieu. It was at this time that he began contributing caricatures, cartoons, and satirical lithographs to student magazines, in particular Le Crocodile which brought him some notoriety. In 1856, Rops, along with Victor Hallaux (pseudonym Victor de la Hesbaye) and Charles De Coster progressed from student magazines to founding their own journal, The Uylenspiegel, a weekly artistic and literary satirical review to which he contributed one or two lithographs an issue, more than 180 total, furthering his reputation.[1]: 243 p. [2][4]: 29 p. [5]: 8-9p. [6][7]

Early career in Belgium, and marriage (1857–1870)

In June 1857, Rops married Charlotte Polet de Faveaux, the daughter of a wealthy magistrate and owner of Thozée Castle (see external links below) in the countryside near the town of Mettet, Belgium. For the first few years at Thozée, Rops enjoyed a comfortable life of a country gentlemen, pursuing passions for painting, botany, and even founding a rowing club in 1862, the Royal Nautical Club of Sambre and Meuse. He spoke highly of his father-in-law in his letters. Rops and his wife had a son, Paul, in 1858, and a daughter, Juliet, in 1859, who died at the age of five. Rops relinquished his managerial roll at Uylenspiegel but continued contributing cartoons and illustrations until 1862. He began to explore etching and produced political lithographs, occasional caricatures and cartoons for magazines, and frontispieces and illustrations for books. He illustrated a number of De Coster's books including Légendes Flamandes (1858), Contes Brabançons (1861) and La Légende d'Uylenspiegel ('Tijl Uilenspiegel', 1867). His home became a gathering place for artists, writers, publishers and friends. The Société Libre des Beaux-Arts (Free Society of Fine Arts) in Brussels was founded in 1868 and Rops served as Vice-President for several years. By the 1860s, Rops was traveling extensively and dividing his time between Thozée Castle, Namur, Brussels, and Paris each year; with ever extending time in Paris at the center of the art and literary world, and ever decreasing time at Thozée Castle and Namur with his wife and family as the decade passed.[1]: 243 p. [2][4]: 30 p. [5]: 9 p. [6][8]

In 1862, he studied etching with Félix Bracquemond and Jules Ferdinand Jacquemart in Paris and he became a restless experimenter with etching techniques. In later years, with his friend Armand Rassenfosse they developed a new soft ground varnish method which was dubbed "Ropsenfosse".[4]: 37 p. His activity as a lithographer had ceased by 1865, and although he continued oil painting, etching became his principal medium. He produced 34 frontispieces for books published between 1864 and 1870 and founded the short-lived International Society of Etchers (1869–1871).[1]: 243 p. [2][4]: 37 p. [5]: 9 p. [8]

Relationship with Charles Baudelaire (1862–1867)

Baudelaire wrote the following tribute to Rops:[4]: 3 p.

Use all your eloquence..../ To say how much I like / That bizarre Mr. Rops / Who may not be a Rome First Prize / But whose talent is as great / As the pyramids of Cheops.

_crayon%252C_ink_(16.2_x_11.2_cm)_private_collection_Namur%252C_Belgium_(detail).jpg.webp)

Rops created the frontispiece for Baudelaire's Les Épaves (The Wreckage) and a selection of poems from Les Fleurs du mal (The Flowers of Evil) that had been censored in France, and were therefore published in Belgium. Rops first met Baudelaire's publisher Auguste Poulet-Malassis in 1862 and was later introduced to Charles Baudelaire towards the end of the poet's life. A friendship developed and Baudelaire visited the Rops family at Thozée Castle on many occasions and they traveled together on at least one occasion. In a letter (25 August 1886) discussing Baudelaire's writing, Rops wrote: "I lived with Baudelaire for two years. and often served him as a secretary, I never once saw him consult a dictionary. He didn't have any, and didn't want to have any...saying 'A man who looks up a word in a dictionary is like a conscript who, upon receiving the order to fire, looks for a cartridge in his pouch.'"[9]: 279 p. In a letter to Édouard Manet (11 May 1865) Baudelaire wrote, "Rops is the only true artist (in the sense in which I, and perhaps I alone, understand the word artist), that I have found in Belgium."[10]: 221 p. By 1866 Baudelaire and Poulet-Malassis were both in Belgium, in self-imposed exile evading creditors. Baudelaire stated that Rops and Poulet-Malassis were the only persons who "lightened [his] sadness in Belgium".[11]

It was while visiting Namur, in March 1866, that Baudelaire's first symptoms of aphasia and hemiplegia became apparent. Rops invited Baudelaire and Poulet-Malassis to visit his hometown, where Baudelaire had seen and admired the baroque Church of Saint-Loup at Namur (see external links below) before, calling it "the masterpiece of Jesuit masterpieces"[12]: 124 p. and stating the stained-glass windows illuminated the interior like a "terrible and delightful catafalque".[10]: 235 p. Baudelaire collapsed on the floor while they were admiring the carving on the confessionals there. Baudelaire never fully recovered and died in August 1867 at the age of 46.[9][10]: 235 p. [11][12]: 339 p.

Baudelaire left an impression upon Rops that lasted until the end of his life. His association with Baudelaire and his illustrations of his poetry helped increase the visibility of his work and win the admiration of many other artists and writers, including Théophile Gautier, Stéphane Mallarmé, Jules Barbey d'Aurevilly, Joséphin Péladan, Puvis de Chavannes, Gustave Moreau, and Edmond and Jules de Goncourt.[2][4]: 41 p. [8][11] By 1870 Rops had made many friends and was living in Paris most of the year and immersed at the heart of literary Paris and the Symbolist and Decadence movements. Taking his cue from Baudelaire's "The Painter of Modern Life", he "cultivated the airs of a dandy".[4]: 41-42 p. Félix Fénéon was to write of him "Rops: Anoints himself with rouge, dyes his hair and wears a blood-red shirt: looks, or so he hopes, like a sarcastic Satan."[1]: 60 p. [13]

Later career in Paris (1871–1898)

The extended months in Paris away from his wife, and his poorly concealed extramarital affairs (described by his biographer Patrick Bade as his "careless contempt for bourgeois family values")[4]: 33 p. took a toll on Rops's marriage by the early 1870s. His wife Charlotte wrote to him in a letter: "Your latest despicable affair, the eighth since I met you and we were married, was your way of punishing others, you killed me! Since you don't want to see me any more and asked me not to write to you any more, I want my last word to you to be a word of pardon".[4]: 30 p. One of his mistresses—Alice Renaud, the woman referred to in his wife's letter—was murdered by her jealous husband a few years later, and Rops was involved in the scandal when his intimate love letters to her were read out loud at her husband's trial.[4]: 33 p. Although they never divorced, by 1875 Félicien and Charlotte were permanently estranged and Paris was to be his home for the remainder of his life.[4]: 30-33 p. [5]: 9 p.

However, far from being disheartened, he thrived among the Parisian artists and poets and his critical reputation grew. There was a greater demand than ever for his illustrations in the last quarter of the 19th century by the publishers and authors of the literary vanguard. Rops was prolific and achieved financial success, boasting in 1877 that "he was the best-paid illustrator in France."[4]: 3–5, 41p. [5]: 10 p. He traveled extensively throughout Europe, ranging from the capital cities and art centers, to salmon fishing in Norway and Sweden, back country ventures in Hungary, as well as Spain and Northern Africa.[5]: 9-10 p. [8] Rops frequently exhibited at the various salons in Paris where the public was both fascinated and shocked by his art and his personal life.[1]: 243 p.

_etching%252C_drypoint_(12.86_x_17.62_cm)_Los_Angeles_County_Museum_of_Art_(detail).tif.jpg.webp)

In the 1860s Rops had developed an acquaintance with a Madame Duluc and her two young daughters, Aurélie and Léontine Duluc (age 14 and 17 respectively at that time).[4]: 33 p. A few years later, not long before the estrangement from his wife, he began a ménage à trois with the sisters, apparently with their mother's endorsement. He had children with both, although one child died at an early age; the other, Claire, daughter of Léontine Duluc born in 1871, went on to marry the Belgian author Eugène Demolder. The Duluc sisters ran Maison Duluc, a successful fashion house in Paris, for which Rops designed logos and provided advertisements. The three traveled together to the United States and Canada on two occasions to present their fashions. At least one of the sisters served as a model on occasion, and one example was the figure illustrated in Georges Camuset's Sonnet du Docteur (The Sonnets of the Doctor; 1884). The three lived together for over 25 years until Rops's death. They ultimately settled in La Demi-Lune, a house he purchased, on the River Seine in Corbeil-Essonnes south of Paris, where Rops continued his passion for botany and developed new varieties of roses in later years. Aurélie and Léontine often combined their names, signing Auréléon in their letters and correspondence with Rops.[4]: 33-37 p. [5]: 10-11 p. [8][14][15]

Rops was invited to join Les XX or Les Vingt, a group of Belgian artists formed in 1883 which held annual exhibitions and concerts at the Palais des Beaux-Arts and the Museum of Modern Art of Brussels. Founders of the Les Vingt included James Ensor, Théo van Rysselberghe, and Fernand Khnopff among others and were later joined by Anna Boch, Jan Toorop, Odilon Redon, and Paul Signac. Their intention was to protect "true originality" and provide a place "where people are free, not only in fact but above all in thought." For 10 years Les Vingt championed the work of progressive artists and composers of the time including many of the Impressionists, Post-Impressionists, Pointillists, and Symbolists.[1]: 50, 106 & 243 pp. The French poet Stéphane Mallarmé held Tuesday evening discussions on the arts and literature at his home on 87 Rue de Rome in Paris. These talks became a place of pilgrimage attended by dozens of writers and artists of the time including Rops, Paul Gauguin, J.-K. Huysmans, Édouard Manet, Edvard Munch, Odilon Redon, Paul-Marie Verlaine, and Emile Zola. He maintained his literary associations to the end of his life and in 1896 the literary revue "La Plume" published a special edition tribute volume devoted exclusively to Rops where many of the prominent authors and artists such as Puvis de Chavannes, Joris-Karl Huysmans, Octave Mirbeau, Josephin Peladan, and Jose-Maria De Heredia praised and celebrated his work.[1]: 48 p. [4]: 5 p. [8] Félicien Rops was a freemason and a member of the Grand Orient of Belgium.[16]

Due to an accident with "bichlorate of potassium"[5]: 10-11 p. in 1892, Rops almost lost his eyesight but he eventually recovered. With his health slowly deteriorating and anticipating legal challenges from his estranged wife Charlotte, his son Paul, and father-in-law, a judge in Belgium, he made a will in July 1896 leaving everything to the Duluc sisters. He spent some time in the south of France with its milder climate on a doctor's orders but it provided only a little relief. In time, legal issues did arise and the Duluc sisters successfully disputed Paul's attempts to have his father removed from their care, but compromise settlements were made on other issues. Rops died on 23 August 1898 at his home, with Aurélie and Léontine Duluc, his daughter Claire, and some close friends at his side. When notified of his imminent death, Paul traveled from Belgium, but arrived too late to see his father alive. Rops was buried in Essonnes but his body was moved to the family burial grounds in Namur, Belgium eight years later.[4]: 37 p. [5]: 11 p. [8] The following year, he was posthumously awarded the Legion of Honour.[8][17]

There is now a Museum, Musée Félicien Rops, in his home town of Namur, Belgium, housing approximately 3,000 engravings and 500 drawings and paintings. Rops also was a gifted and prolific writer of letters. Referring to Rops, Edgar Degas told Manet "That one writes even better than he engraves [...]. If they ever publish his correspondence, I’ll sign up for a thousand copies of propaganda"[8] The Félicien Rops Museum has documented and indexed over 4,000 letters so far, over half are currently available online (see External Links below).[8] His correspondences serve as valuable documents and references, not only for Rops and his work, but for the numerous artists, writers, publishers, and other notable culture figures of late 19th century Europe. The biographers of Baudelaire have drawn from Rops's letters extensively (e.g.[9]: 279, 328, 351, 404, 407, 409 pp. ).

Art

Art historians do not consider Rops a seminal figure of late 19th century art, even among the symbolists, and yet no creditable review of symbolism could ignore him either. Some of his critics dismiss him as a novel, 19th-century illustrator/pornographer, but others look beyond the erotica and write of him respectfully and favorably.[1]: 243 p. [2][18][19] He was regarded as the greatest Belgian artist of his time by Baudelaire (an influential art critic as well as a poet).[20] Jean-Luc Daval spoke of "the amazing upsurge of Symbolism that in the wake of Félicien Rops and under the influence of Gustave Moreau, characterized Belgian painting at the turn of the century."[21]: 105 p. According to Edith Hoffmann, the "erotic or frankly pornographic" nature of much of Rops's work "is at least partly due to the attraction these subjects had for a provincial artist who never forgot his first impressions of Paris".[6] In contrast to Hoffmann's "provincial artist", Octave Mirbeau wrote "Painter, man of letters, philosopher, scholar, Rops was all of that."[4]: 94 p.

Félicien Rops was a prolific and versatile artist. In addition to works of fine art depicting genre subjects, still-life, landscapes, decadent nightlife, eroticism, and iconic symbolist works like Pornocrates, he produced hundreds of comics, caricatures, book illustrations, and even an occasional advertisement. His style could sway from realism, to symbolism, and at times even touch on romanticism and impressionism. His images can be pastoral (e.g. The Rocks of the Grands Malades) or urban (e.g. Sailors Den); social and political critiques both sympathetic (e.g. Strike, The Charcoal) and caustic (e.g. Order Reigns in Warsaw); documentary (e.g. Head of Zealander) or fantasy (e.g. The Librarian); and range from poetic and metaphoric (e.g. The Lyre) to stark realism (e.g. Absinthe Drinker). Three etchings depicting animals illustrate a wide display of approaches in styles, techniques, and underlying connotations (see gallery II). Japanese Salamander and Beetle is loose in technique and a simple, decorative nature study, one of a few pastiches Rops made of Japanese woodblock printing that were popular and influential among European artists in the late 19th century.[5]: 10 p. [22]: 56 p. The Cat, executed in an illustrative, near academic style, presents a pleasant likeness of a cat, yet embroidered on the chair is the phrase "Amica Non Serva" [Friend Not Servant], endowing this unassuming image with a declaration of sovereignty not immediately apparent to the casual viewer. Separated or Simian Spring uses an abrupt and serrated hatching technique to convey primitive, psycho-sexual undertones that anticipates expressionism in the early 20th century.[2][8][18]

French art critic and historian Jean Cassou posited three distinct periods in Rops's artistic life: romantic 1855–1860; symbolist 1860–1870; realist 1871–1898.[2] While these dates are not supported by others,[8][5] and are contrary to even the most cursory examination of the work [e.g., symbolist works such as Pornocrates (1878); Les Sataniques (1882); The Lyre frontispiece for Poésies by Mallarmé (1895); and Parallelism, the frontispiece for Chair [Flesh] by Verlaine (1896) were produced in Cassou's posited "realist 1871–1898" period], Cassou's association of Rops with realism is valid and important in understanding his work. Whether drawing genre subjects or decadent Parisian nightlife, Rops produced realist images throughout his artistic life and they constitute a significant part of his oeuvre. This aspect of his work is often marginalized or ignored by authors who are preoccupied with his erotic and satanic images (enthusiastically or negatively).[2][8][18]

Working in a long and rich tradition of Franco-Flemish realist-genre painting (e.g., the Le Nain Brothers, Adriaen Brouwer) but also showing an awareness and influence of contemporaries like Honoré Daumier, Jean-François Millet, and Gustave Courbet, Rops was attracted to genre subjects throughout his life. Although represented in any number of media, they most often appear in his drawings and etchings. The rural and working people of the Walloon region of Belgium were frequent subjects, typically treated in a simple and sympathetic manner, as in The Kitchen of the Artists' Inn, in Anseremme. The elderly appear again and again in works such as Old Kate. Rops also often drew and etched people he encountered in his travels who were dressed in ethnic and regional clothing and costumes, often in a rather documentary style. Two examples include A Shaker Pianist and Head of Zealander: others are La Dalécarlienne (1874), Le Moujick (1874), and In the Pusta (1879). Rops once wrote he had "the desire to depict the scenes and characters of the 19th century that I find so fascinating and curious"[5]: 10 p. and pieces like Sailors Den, Cherub's Song, and The Absinthe Drinker can be viewed as works of realism just as they can be seen as works of the decadent movement.[2][8][18]

Rops once wrote: "The love of brutal pleasures, the pre-occupation with money, and mean interests have glued onto the faces of most of our contemporaries, a sinister mask in which the perverse instinct mentioned by Edgar Allan Poe can be read in capital letters: all of this seems to me sufficiently amusing and characteristic that well-meaning artists should attempt to render the look of their time".[4]: 45 p.

According to H. R. Blakeley, "scholarship about Rops disproportionately fixates on the erotic aspects of his art, reductively classifying him as perversely misogynistic instead of investigating the complexities of his relationships with and attitudes about women."[18]

Painting and drawing

Rops's oil paintings are varied in subject and style. They include still life paintings, street scenes such as Entrance to the Ball, the Symbolist Death at the Ball, and many landscapes. He painted landscapes throughout his career, often small canvases done in En plein air. Examples like The Rocks of the Grands Malades and Snow in Thozée were painted in the vicinity of his hometown Namur, in the Walloon region of southern Belgium. The influences of Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Gustave Courbet, and the Barbizon School can be detected in many of his landscapes. Living in Paris and exhibiting with Les XX, Rops had ample opportunity to meet artists and absorb the work of the schools and movements of the day, and elements of impressionism are evident in The Beach in Heist, painted on the Belgian coast.[2][8]

A small series of variations on a theme, The Lady with the Puppet includes four drawings with mixed media (watercolor, color pencil, pastel etc.) that were executed between 1873 and 1890. These symbolist works each show a woman, a "simple tart",[8] playing with a puppet (an allegory of man). In one, the woman unassumingly holds a blood-smeared trailing point at her side, with which she has slit the belly of the puppet open, and amusingly holds the puppet high as gold coins drain from his limp body.[8]

About 1878–1881 Rops produced a large series of over 100 pieces he called Cent légers croquis pour réjouir les honnêtes gens (A hundred lighthearted sketches without pretension to delight honest people) for a Parisian bibliophile, Jules Noilly. These were made in a variety of mixed media, mostly works on paper, including drawing, color pencil, watercolor, gouache, and pastel. Examples from the series include The Human Parody, The Librarian, L'Amour Mouché, Venus and Cupid-Love blowing his nose, and Cherub's Song.[4]: 38, 41, 42, 54, 75, & 82 pp. [8]

Gallery I: paintings and drawings

Entrance to the Ball (ca. 1858) Oil on canvas, mounted on board (29.5 x 21 cm) Musée Félicien Rops, Namur, Belgium

Entrance to the Ball (ca. 1858) Oil on canvas, mounted on board (29.5 x 21 cm) Musée Félicien Rops, Namur, Belgium_De_dood_op_het_bal_-_Kr%C3%B6ller-M%C3%BCller_Museum_Otterlo_23-08-2016_13-31-56.JPG.webp) Death at the Ball (ca. 1865–1875) oil on canvas (150 x 85 cm) Kröller-Müller Museum, Netherlands

Death at the Ball (ca. 1865–1875) oil on canvas (150 x 85 cm) Kröller-Müller Museum, Netherlands_mixed_media_on_paper_(39_x_48_cm)_Mus%C3%A9e_F%C3%A9licien_Rops%252C_Namur.jpg.webp) The Drunken Dandy (no date) mixed media on paper (39 x 48 cm) Musée Félicien Rops, Namur

The Drunken Dandy (no date) mixed media on paper (39 x 48 cm) Musée Félicien Rops, Namur_watercolor%252C_pastel%252C_gouache_(60.5_x_46.5_cm)_Mus%C3%A9e_F%C3%A9licien_Rops%252C_Namur.jpg.webp) Sailors Den (1875) watercolor, pastel, gouache (60.5 x 46.5 cm) Musée Félicien Rops, Namur

Sailors Den (1875) watercolor, pastel, gouache (60.5 x 46.5 cm) Musée Félicien Rops, Namur_watercolor%252C_pastel%252C_chalk_(22.5_x_15cm).jpg.webp) The Human Parody (1878–1881) watercolor, pastel, chalk (22.5 x 15 cm)

The Human Parody (1878–1881) watercolor, pastel, chalk (22.5 x 15 cm) The Librarian, (1878–1881) pencil, watercolor, gouache (22 x 14.5 cm) Namur

The Librarian, (1878–1881) pencil, watercolor, gouache (22 x 14.5 cm) Namur_pastel%252C_gouache%252C_chalk_(21.8_x_14.8)_Mus%C3%A9e_F%C3%A9licien_Rops%252C_Namur.jpg.webp) L'Amour Mouché, Venus and Cupid-Love blowing his nose (1878–1881) mixed media (22 x 15) Musée Félicien Rops, Namur

L'Amour Mouché, Venus and Cupid-Love blowing his nose (1878–1881) mixed media (22 x 15) Musée Félicien Rops, Namur In the wings (1878–1880) watercolor, colored pencil, and pastel (26 x 16.5 cm) Musée Félicien Rops, Namur, Belgium

In the wings (1878–1880) watercolor, colored pencil, and pastel (26 x 16.5 cm) Musée Félicien Rops, Namur, Belgium Cherub's Song (1878–1881) watercolor, gouache, pastel, chalk (22 x 15 cm) Musée Félicien Rops, Namur

Cherub's Song (1878–1881) watercolor, gouache, pastel, chalk (22 x 15 cm) Musée Félicien Rops, Namur After Midnight, Returning makes you appreciate absence (no date) mixed media (22 x 15 cm) Private collection

After Midnight, Returning makes you appreciate absence (no date) mixed media (22 x 15 cm) Private collection_color_pencil%252C_watercolor%252C_gouache_(30.5_x_23.6_cm.)_Namur.jpg.webp) Prehistoric Coupling (1887) color pencil, watercolor, gouache (30.5 x 23.6 cm.) Namur

Prehistoric Coupling (1887) color pencil, watercolor, gouache (30.5 x 23.6 cm.) Namur Temptation of Saint Anthony (1878) mixed media (74 x 54) Royal Library of Belgium, Brussels

Temptation of Saint Anthony (1878) mixed media (74 x 54) Royal Library of Belgium, Brussels_watercolor%252C_colored_pencil_(22.9_x_28.6_cm)_Metropolitan_Museum_of_Art%252C_New_York.jpg.webp) Untitled (no date) watercolor, colored pencil (22.9 x 28.6 cm) Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Untitled (no date) watercolor, colored pencil (22.9 x 28.6 cm) Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York The Lady with the Puppet (ca. 1883–1885) mixed media (39.4 x 27.4 cm) Musée Félicien Rops, Namur

The Lady with the Puppet (ca. 1883–1885) mixed media (39.4 x 27.4 cm) Musée Félicien Rops, Namur Paul Rops Sleeping (ca. 1872–75), oil on canvas (size unknown) Félicien Rops Fund, Namur, Belgium

Paul Rops Sleeping (ca. 1872–75), oil on canvas (size unknown) Félicien Rops Fund, Namur, Belgium_oil_on_canvas_(22%252C5_x_32_cm)_Friends_of_the_Mus%C3%A9e_F%C3%A9licien_Rops.jpg.webp) Pears and Apple on a Plate (1882) oil on canvas (22,5 x 32 cm) Friends of the Musée Félicien Rops, Namur

Pears and Apple on a Plate (1882) oil on canvas (22,5 x 32 cm) Friends of the Musée Félicien Rops, Namur_Les_Rochers_des_Grands_Malades._Mus%C3%A9e_des_Beaux_Arts_Ixelles.jpg.webp) The Rocks of the Grands Malades (1876) oil on canvas, Musée des Beaux Arts Ixelles

The Rocks of the Grands Malades (1876) oil on canvas, Musée des Beaux Arts Ixelles Snow in Thozée (no date) oil on canvas, Belfius Bank & Insurance, Brussels

Snow in Thozée (no date) oil on canvas, Belfius Bank & Insurance, Brussels_oil_on_panel_(18.5_%C3%97_24_cm)_Charleroi_Museum_of_Fine_Arts.jpg.webp) The Pond of Bambois (1865) oil on panel (18.5 × 24 cm) Charleroi Museum of Fine Arts

The Pond of Bambois (1865) oil on panel (18.5 × 24 cm) Charleroi Museum of Fine Arts_Meer_van_Bambois_-_Mus%C3%A9e_F%C3%A9licien_Rops_Namen_23-03-2018_10-25-23.jpg.webp) More from Bambois (no date) oil on canvas, Musée Félicien Rops, Namur, Belgium

More from Bambois (no date) oil on canvas, Musée Félicien Rops, Namur, Belgium_Het_strand_in_Heist_(1886)_Mus%C3%A9e_F%C3%A9licien_Rops_Namen_23-03-2018_10-27-00.jpg.webp) The Beach in Heist (1886) oil on canvas, Musée Félicien Rops Namen, Belgium

The Beach in Heist (1886) oil on canvas, Musée Félicien Rops Namen, Belgium

Prints and book illustrations

"Rops was a printmaker of brilliant technique and original content whose handling of dry point (etching directly on the plate) marks him as one of the masters of the medium."[19] Although Rops worked in a wide range of media, his primary means of expression was printmaking. He worked with lithography, wood engraving, etching, aquatint, mezzotint, soft-ground etching, burin engravings, heliogravure and other techniques producing hundreds of prints in his life. His prints are remarkably diverse and span the full spectrum of the styles and subject matter that he explored throughout his life. He begin shifting from lithography to intaglio in the 1860s when he studied etching with Félix Bracquemond and Jules Ferdinand Jacquemart in Paris. Félix Bracquemond was one of the central figures in reviving an interest in etching among artists of the time, encouraging and coaching artists such as Édouard Manet, Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro, and others to explore the neglected art form. By the end of the decade Rops had all but abandoned lithography. Rops founded the International Society of Etchers about 1869 or 1870. Although the society received praises from artists and royalty alike, financially he struggled to keep it going for more than two to three years.[1]: 243 p. [2][4]: 37 p. [5]: 9 p. [8][18][23]: 216 p.

Fascinated by the processes, he was constantly experimenting with printmaking techniques throughout his career. Starting around the early 1870s, Rops begin using soft-ground etching, a technique practiced by few artists of his day, often combining it with mezzotint, aquatint, dry point, and other techniques, sometimes adding hand-coloring to the plates. He photo-mechanically (heliogravure) transferred many of his original drawings to intaglio plates, and often developed the images further in that medium with any number of techniques such as dry point, aquatint, soft-ground etching, etc. However, traditional soft-ground methods did not work well for his purposes, so in collaboration with his friend and colleague Armand Rassenfosse, they invented a process they called "Ropsenfosse". Ropsenfosse used several different soft-ground formulas and was likely the first soft-ground method used to produce color prints with two or more plates.[6][18][24]

His etchings were popular and many of the progressive writers, poets, and publishers of late 19th-century literature sought out his talents for their publications. His prints were widely distributed in the books he illustrated and influenced many younger artists, including several Symbolists and Expressionist such as Max Beckmann, Lovis Corinth, James Ensor, Alfred Kubin, Fernand Khnopff, Max Klinger, Edvard Munch and others. The Blue Angel largely was inspired by a figure by Rops that impressed director Josef von Sternberg.[6][25][26]: 81 [27]: 15, 18, 26 pp. [28]: 20, 25–26, 62–63, 109 pp.

Gallery II: prints and book illustrations

Frontispiece for Les Épaves by Baudelaire (1868) etching (16 x 13,3 cm) Musée Félicien Rops, Namur

Frontispiece for Les Épaves by Baudelaire (1868) etching (16 x 13,3 cm) Musée Félicien Rops, Namur_etching_and_aquatint_(11.75_x_7.78_cm)_Los_Angeles_County_Museum_of_Art.tiff.jpg.webp) Frontispiece for The Supreme Vice by Peladan (1884) etching and aquatint (11.75 x 7.78 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art

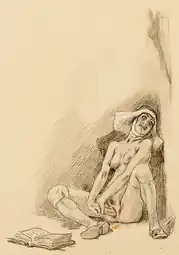

Frontispiece for The Supreme Vice by Peladan (1884) etching and aquatint (11.75 x 7.78 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art_soft-ground_etching_(16.67_x_10.8_cm)_Los_Angeles_County_Museum.tiff.jpg.webp) Frontispiece for A Heart Lost by Peladan (1888) soft-ground etching (16.67 x 10.8 cm) Los Angeles County Museum

Frontispiece for A Heart Lost by Peladan (1888) soft-ground etching (16.67 x 10.8 cm) Los Angeles County Museum_(1895)_soft-ground_and_drypoint_(22.8_x_15.7_cm)_Los_Angeles_County_Museum_of_Art.tif.jpg.webp) Frontispiece for Poésies by Mallarmé, The Lyre (1895) etching & drypoint (23 x 16 cm) L.A. Co. Museum

Frontispiece for Poésies by Mallarmé, The Lyre (1895) etching & drypoint (23 x 16 cm) L.A. Co. Museum![Frontispiece for Chair [Flesh] by Verlaine, Parallelism (ca. 1896) heliogravure (33.5 × 21.2 mm) The Art Institute of Chicago](../I/Felicien_Rops%252C_Parallelism_(ca._1896)_heliogravure_(33.5_%C3%97_21.2_mm)_The_Art_Institute_of_Chicago.jpg.webp) Frontispiece for Chair [Flesh] by Verlaine, Parallelism (ca. 1896) heliogravure (33.5 × 21.2 mm) The Art Institute of Chicago

Frontispiece for Chair [Flesh] by Verlaine, Parallelism (ca. 1896) heliogravure (33.5 × 21.2 mm) The Art Institute of Chicago Sainte-Thérèse (no date) heliogravure (15 x 11 cm) various locations.

Sainte-Thérèse (no date) heliogravure (15 x 11 cm) various locations._heliogravure_(29.2_x_17.2_cm)_Michael_C._Carlos_Museum%252C_Emory_University%252C_Atlanta.jpg.webp) Parisian Masks (no date) heliogravure (29.2 x 17.2 cm) Michael C. Carlos Museum, Emory University, Atlanta

Parisian Masks (no date) heliogravure (29.2 x 17.2 cm) Michael C. Carlos Museum, Emory University, Atlanta_(1895)_heliogravure_retouched_with_drypoint_(21.6_x_15.2_cm)_Michael_C._Carlos_Museum%252C_Emory_University%252C_Atlanta.jpg.webp) Holocauste, Naturalia Non Sunt Turpia (What is natural is not dirty) (1895) heliogravure, drypoint (21.6 x 15.2 cm) Michael C. Carlos Museum, Emory University, Atlanta

Holocauste, Naturalia Non Sunt Turpia (What is natural is not dirty) (1895) heliogravure, drypoint (21.6 x 15.2 cm) Michael C. Carlos Museum, Emory University, Atlanta_heliogravure%252C_Michael_C._Carlos_Museum%252C_Emory_University%252C_Atlanta.jpg.webp) Sentimental Initiation (1887) heliogravure, Michael C. Carlos Museum, Emory University, Atlanta

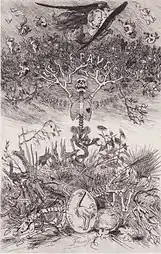

Sentimental Initiation (1887) heliogravure, Michael C. Carlos Museum, Emory University, Atlanta The Dance of Death (ca. 1865) etching (55 x 37 cm)

The Dance of Death (ca. 1865) etching (55 x 37 cm)_aquatint_(12.07_x_9.53_cm)_Los_Angeles_County_Museum_of_Art.tif.jpg.webp) Flemish Madness (no date) aquatint (12.07 x 9.53 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Flemish Madness (no date) aquatint (12.07 x 9.53 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art_aquatint_(9.21_x_6.67_cm)_Los_Angeles_County_Museum.tif.jpg.webp) Japanese Salamander and Beetle (no date) aquatint (9.21 x 6.67 cm) Los Angeles County Museum

Japanese Salamander and Beetle (no date) aquatint (9.21 x 6.67 cm) Los Angeles County Museum![The Cat [Amica Non Serva, Friend Not Servant] (no date) etching (8.26 x 5.87 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art](../I/lossy-page1-174px-Felicien_Rops%252C_The_Cat%252C_Amica_Non_Serva%252C_Friend_Not_Servant_(_no_date)_etching_(8.26_x_5.87_cm)_Los_Angeles_County_Museum_of_Art.tif.jpg.webp) The Cat [Amica Non Serva, Friend Not Servant] (no date) etching (8.26 x 5.87 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art

The Cat [Amica Non Serva, Friend Not Servant] (no date) etching (8.26 x 5.87 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art_etching_with_aquatint_(6.51_x_9.68_cm)_Los_Angeles_County_Museum_of_Art.tif.jpg.webp) Separated or Simian Spring (no date) etching with aquatint (6.51 x 9.68 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Separated or Simian Spring (no date) etching with aquatint (6.51 x 9.68 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art_heliogravure_(335_%C3%97_225_mm)_Art_Institute_of_Chicago.jpg.webp) The Absinthe Drinker (1853–1898) heliogravure (335 × 225 mm) Art Institute of Chicago

The Absinthe Drinker (1853–1898) heliogravure (335 × 225 mm) Art Institute of Chicago_heliogravure_(24_x_18_cm)_Michael_C._Carlos_Museum%252C_Emory_University%252C_Atlanta.jpg.webp) Mam'zelle Gavroche and Erotic Poetry (1879) heliogravure (24 x 18 cm) Michael C. Carlos Museum, Emory University, Atlanta

Mam'zelle Gavroche and Erotic Poetry (1879) heliogravure (24 x 18 cm) Michael C. Carlos Museum, Emory University, Atlanta_heliogravure_(24.61_x_15.24_cm)_Los_Angeles_County_Museum_of_Art.tif.jpg.webp) Celle qui fait 'Celle qui lit Musset' (1879) heliogravure (24.61 x 15.24 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Celle qui fait 'Celle qui lit Musset' (1879) heliogravure (24.61 x 15.24 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art_etching_(16.99_x_11.75_cm)_)_Los_Angeles_County_Museum_of_Art_II.tif.jpg.webp) A Shaker Pianist (1888) etching (16.99 x 11.75 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art

A Shaker Pianist (1888) etching (16.99 x 11.75 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art_etching%252C_drypoint_(19.8_x_15.2_cm)_Michael_C._Carlos_Museum%252C_Emory_University%252C_Atlanta.jpg.webp) The Strike (1876) etching, drypoint (19.8 x 15.2 cm) Michael C. Carlos Museum, Emory University, Atlanta

The Strike (1876) etching, drypoint (19.8 x 15.2 cm) Michael C. Carlos Museum, Emory University, Atlanta_soft-ground_etching_(19.69_x_23.65_cm)_Los_Angeles_County_Museum_of_Art.tif.jpg.webp) Head of Zealander (1886) soft-ground etching (19.69 x 23.65 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Head of Zealander (1886) soft-ground etching (19.69 x 23.65 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art_heliogravure_%2526_roulette_(25.9_x_19.5_cm)_Michael_C._Carlos_Museum%252C_Emory_University%252C_Atlanta.jpg.webp) Old Kate (1895) heliogravure & roulette (25.9 x 19.5 cm) Michael C. Carlos Museum, Emory University, Atlanta

Old Kate (1895) heliogravure & roulette (25.9 x 19.5 cm) Michael C. Carlos Museum, Emory University, Atlanta_Een_begrafenis_in_het_Waalse_land_(1863)_litho_-_Mus%C3%A9e_F%C3%A9licien_Rops_Namen_23-03-2018_10-17-45.JPG.webp) Funeral in the Walloon Country (1863) lithograph, Musée Félicien Rops, Namen, Belgium

Funeral in the Walloon Country (1863) lithograph, Musée Félicien Rops, Namen, Belgium_etching_(19.84_x_12.86_cm)_Los_Angeles_County_Museum_of_Art.tiff.jpg.webp) Jean Brouette (1875) etching (19.84 x 12.86 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Jean Brouette (1875) etching (19.84 x 12.86 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art_heliogravure%252C_drypoint_(16.3_x_11.4_cm)_Michael_C._Carlos_Museum%252C_Emory_University%252C_Atlanta.jpg.webp) Parable of the Sower (no date) heliogravure, drypoint (16.3 x 11.4 cm) Michael C. Carlos Museum, Emory University, Atlanta

Parable of the Sower (no date) heliogravure, drypoint (16.3 x 11.4 cm) Michael C. Carlos Museum, Emory University, Atlanta_etching_(19.05_x_13.81_cm)_Los_Angeles_County_Museum_of_Art.tif.jpg.webp) The Kitchen of the Artists' Inn, in Anseremme (no date) etching (19.05 x 13.81 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art

The Kitchen of the Artists' Inn, in Anseremme (no date) etching (19.05 x 13.81 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Les Sataniques and Les Diaboliques

As early as 1896, when a special tribute edition of the literary journal La Plume (No. 172, 15 June) was published honoring Rops, the illustrations he produced for d'Aurevilly's Les Diaboliques as well as an earlier series, Les Sataniques were often singled out and "placed at the top of the ropsian pantheon" and considered the "paradigm of the Ropsian work".[29]: 1 p. Subsequent critics, historians, as well as his admirers among the general public have consistently regarded these prints as among the best examples of his illustrative oeuvre. Art historian Robert L. Delevoy wrote "His etchings for Les Diaboliques by Barbey d'Aurevilly are regarded as some of the best illustrative work ever done."[4]: 86 p. [1]: 243 p. [2]

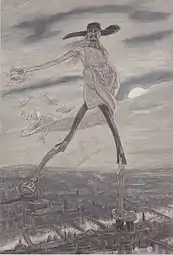

Les Sataniques (The Satanic) was a series of his own initiative, independent of his book illustrations and literary works. Dating from about 1882, there are a number of closely related drawings, watercolors, sketches, and other mixed media pieces, as well as prints in various states of development. He had hoped to do a large series and eventually publish them in the form of a book, but this never came to fruition. Ultimately a set of five heliogravures (based on five original drawings) were published, including: Satan semant l'ivraie (Satan Sowing Tare), L'enlèvement (The Abduction), Le Calvaire (The Calvary), L'idole (The Idol), and Le Sacrifice (The Sacrifice). The frontispiece of the cycle, Satan Sowing Tare, which appeared in several versions, was based on the Biblical Parable of the Tares which appears in Matthew 13:24-13:30. This series ranks among the more familiar and discussed images of his work. There is nothing in the dozens of references below to suggest that Rops was actively involved or a believer in Satanism, and his use of this subject was only symbolic or metaphoric.[1]: 243 p. [8]

Gallery III: Les Sataniques

Satan Sowing Tares (1882) chromolithograph (30.4 x 21 cm) Musèe Félicien Rops

Satan Sowing Tares (1882) chromolithograph (30.4 x 21 cm) Musèe Félicien Rops_etching%252C_aquatint_(27.7_x_20.9_cm)_National_Gallery_of_Art%252C_Washington%252C_DC.jpg.webp) Satan Sowing Tare (1882) etching, aquatint (27.7 x 20.9 cm) National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Satan Sowing Tare (1882) etching, aquatint (27.7 x 20.9 cm) National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC_heliogravure_(_27.8_x_20_cm)_Michael_C._Carlos_Museum%252C_Emory_University%252C_Atlanta.jpg.webp) The Abduction (1882) heliogravure (27.8 x 20 cm) Michael C. Carlos Museum, Emory University, Atlanta

The Abduction (1882) heliogravure (27.8 x 20 cm) Michael C. Carlos Museum, Emory University, Atlanta_heliogravure_(ca._27_x_20_cm)_Museum_De_Reede.jpg.webp) Le Calvaire (1882) heliogravure (ca. 27 x 20 cm) Museum De Reede, Antwerp

Le Calvaire (1882) heliogravure (ca. 27 x 20 cm) Museum De Reede, Antwerp_heliogravure_(27.6_x_20_cm)_Michael_C._Carlos_Museum%252C_Emory_University%252C_Atlanta.jpg.webp) The Idol (1882) heliogravure (27.6 x 20 cm) Michael C. Carlos Museum, Emory University, Atlanta

The Idol (1882) heliogravure (27.6 x 20 cm) Michael C. Carlos Museum, Emory University, Atlanta_soft_ground_etching%252C_reproduced_in_heliogravure_(27.6_x_20.3_cm)_Metropolitan_Museum_of_Art%252C_New_York.jpg.webp) The Sacrifice (ca. 1882) soft ground etching, reproduced in heliogravure (27.6 x 20.3 cm) Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Sacrifice (ca. 1882) soft ground etching, reproduced in heliogravure (27.6 x 20.3 cm) Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York_soft-ground_etching_(15.88_%C3%97_31.75_cm)_Los_Angeles_County_Museum_of_Art.tif.jpg.webp) Satan Throwing to the World the Food She Deserves (no date) soft-ground etching (15.88 × 31.75 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Satan Throwing to the World the Food She Deserves (no date) soft-ground etching (15.88 × 31.75 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art_Los_Angeles_County_Museum_of_Art.tif.jpg.webp) Genesis from Les Sataniques (ca. 1882) soft-ground etching (18.89 x 25.56 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Genesis from Les Sataniques (ca. 1882) soft-ground etching (18.89 x 25.56 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art_soft-ground_etching_(13.1_x_19.6_cm)_Los_Angeles_County_Museum_of_Art.tif.jpg.webp) Satan Creating the Monsters from Les Sataniques (no date) soft-ground etching (13.1 x 19.6 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Satan Creating the Monsters from Les Sataniques (no date) soft-ground etching (13.1 x 19.6 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Les Diaboliques (The She-Devils) is a collection of six short stories by Jules-Amédée Barbey d’Aurevilly that was first published in 1874. Each story is centered around a bored, bourgeois woman, usually involved in a crime of violent depravity or act of revenge. The book was an instant success and quickly sold out. The uproar caught the attention of the Public Prosecutor, the book was banned, the author and publisher were charged with insulting public morality, and set to be put on trial. However, with the aid of Léon Gambetta, a sympathetic statesman, a trial was avoided. Rops did not illustrate the first edition. Laws granting the freedom of the press in France were passed on 29 July 1881 and a second edition of the book was planned by the publisher, Alphonse Lemerre, who thought Rops was ideally suited to illustrate the new edition. Rops provided Lemerre with designs for the illustrations in the form of drawings, but the actual production of the etchings is believed to have been delegated to others. The first set of etchings is referred to as the "Lemerre format", or small boards [plates], and likely date from 1882 when the second edition of the book was published. However Delaporte, in his thesis, discuses a myriad of inconsistency involving the production and dates of the small etchings and suggest they could have appeared ca. 1882–1886.[29]: 2-3 pp. [30]

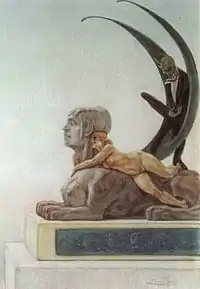

Rops wrote in a letter to Jean-François Taelemans (8 April 1886) that he was unsatisfied and the "small boards do not say anything".[29]: 13 p. He began a second set based on the original drawings using a heliogravure technique, which he then reworked by hand with aquatint, soft-ground varnish, drypoint, etc. The heliogravure prints gave Rops a greater ability to exhibit subtleties and nuances of light and shadow in the dark, nocturnal images. Apparently La Vengeance d'une Femme (The Vengeance of a Woman) was not reproduced in the heliogravure set. The second, heliogravure set, is referred to as the large boards. Like the small boards, the history of the production and dates of the large boards involve many inconsistencies, contradictions, and other issues, but date from ca.1887-1893.[29]: 13-17 pp. The Les Diaboliques illustrations includes nine prints: the frontispiece Le Sphinx (The Sphinx); a prescript La Prostitution et la folie dominant le monde (Prostitution and Madness Rule the World); an illustration for each chapter, Le Rideau Cramoisi (The Crimson Curtain); Le plus bel amour de Don Juan (The Greatest Love of Don Juan); Le bonheur le dans le crime (Happiness in Crime); À un dîner d’athées (At a Dinner of Atheists); Le Dessous de Cartes d'une Partie de Whist (Beneath the Cards in a Game of Whist); La Vengeance d'une Femme (The Vengeance of a Woman); and a postscript La Femme et la folie dominant le monde (Woman & Madness Rule the World).[29]: 3 p. [30]

The print of The Greatest Love of Don Juan bears a striking similarity to Edvard Munch's famous painting Puberty painted in 1894. As early as 1894, with the first publication ever devoted to Munch, comparisons have been made. Munch denied having been influenced by Rops's etching, and said his painting was a copy of another painting he had made in the mid 1880s and "that this earlier version had been lost in a studio fire."[31] Nonetheless, art critics and historians have consistently noted the similarities.[4]: 5 p. [31][32][33][34]: 195 p.

Gallery IV:Les Diaboliques

_hand-colored_lithograph_(27.31_x_22.86_cm)_Los_Angeles_County_Museum_of_Art.tiff.jpg.webp) Caricature of Barbey d'Aurevilly (no date) hand-colored lithograph (27.31 x 22.86 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Caricature of Barbey d'Aurevilly (no date) hand-colored lithograph (27.31 x 22.86 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art The Sphinx, illustration for Les Diaboliques by Jules Barbey d'Aurevilly (1879) pencil & watercolor (25 x 18 cm) Brussels

The Sphinx, illustration for Les Diaboliques by Jules Barbey d'Aurevilly (1879) pencil & watercolor (25 x 18 cm) Brussels_soft-ground_etching_(11.75_x_7.94_cm)_Los_Angeles_County_Museum_of_Art.tiff.jpg.webp) The Sphinx (ca.1887-1893) heliogravure, soft-ground etching (11.75 x 7.94 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art

The Sphinx (ca.1887-1893) heliogravure, soft-ground etching (11.75 x 7.94 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art_soft-ground_etching_(24.45_x_16.67_cm)_Los_Angeles_County_Museum_of_Art.tiff.jpg.webp) Prostitution and Madness Rule the World (ca.1887-1893) heliogravure, soft-ground etching (24 x 16 cm) L.A. County Museum of Art

Prostitution and Madness Rule the World (ca.1887-1893) heliogravure, soft-ground etching (24 x 16 cm) L.A. County Museum of Art_heliogravure_with_aquatint_and_soft_varnish_(237_%C3%97_165_mm)_Art_Institute_of_Chicago_II.jpg.webp) The Crimson Curtain (ca. 1887–93) heliogravure, aquatint and soft varnish (23.7 × 16.5 cm) Art Institute of Chicago

The Crimson Curtain (ca. 1887–93) heliogravure, aquatint and soft varnish (23.7 × 16.5 cm) Art Institute of Chicago_etching%252C_drypoint%252C_aquatinte_(23.5_x_16.2_cm)_Royal_Library_of_Belgium.jpg.webp) The Greatest Love of Don Juan (ca. 1887–93) heliogravure, etching, drypoint, aquatinte (23.5 x 16.2 cm) Royal Library of Belgium

The Greatest Love of Don Juan (ca. 1887–93) heliogravure, etching, drypoint, aquatinte (23.5 x 16.2 cm) Royal Library of Belgium_etching%252C_dry_point%252C_aquatint_(23.8_x_16.5_cm)_Royal_Library_of_Belgium.jpg.webp) Happiness in Crime (ca. 1887–93) heliogravure, etching, dry point, aquatint (23.8 x 16.5 cm) Royal Library of Belgium

Happiness in Crime (ca. 1887–93) heliogravure, etching, dry point, aquatint (23.8 x 16.5 cm) Royal Library of Belgium_heliogravure%252C_aquatint%252C_soft-ground_varnish_(24.8_x_16.6_cm)_Royal_Library_of_Belgium.jpg.webp) At a Dinner of Atheists (ca. 1887–93) heliogravure, aquatint, soft-ground varnish (24.8 x 16.6 cm) Royal Library of Belgium

At a Dinner of Atheists (ca. 1887–93) heliogravure, aquatint, soft-ground varnish (24.8 x 16.6 cm) Royal Library of Belgium_heliogravure_(9.05_x_6.03_cm)_Los_Angeles_County_Museum_of_Art.tif.jpg.webp) Beneath the Cards in a Game of Whist (ca. 1887–93) heliogravure (24.2 x 16.3 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Beneath the Cards in a Game of Whist (ca. 1887–93) heliogravure (24.2 x 16.3 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art_etching_(12.38_x_9.05_cm)_Los_Angeles_County_Museum_of_Art.tif.jpg.webp) The Vengeance of a Woman (c. 1882–1886) etching (12.38 x 9.05 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art

The Vengeance of a Woman (c. 1882–1886) etching (12.38 x 9.05 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art_heliogravure_(9.05_x_6.03_cm)_Los_Angeles_County_Museum_of_Art.tif.jpg.webp) Woman & Madness Rule the World (ca. 1887–93) heliogravure (24.2 x 16.3 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Woman & Madness Rule the World (ca. 1887–93) heliogravure (24.2 x 16.3 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art_etching_(12.38_x_9.05_cm)_Los_Angeles_County_Museum_of_Art.jpg.webp) Happiness in Crime (1882) etching (12.38 x 9.05 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Happiness in Crime (1882) etching (12.38 x 9.05 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art_etching_(12.38_x_8.73_cm)_Los_Angeles_County_Museum_of_Art.tif.jpg.webp) At a Dinner of Atheists, (1882–86) etching (12.38 x 8.73 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art

At a Dinner of Atheists, (1882–86) etching (12.38 x 8.73 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art_etching_(12.38_x_9.05_cm)_Los_Angeles_County_Museum_of_Art.tif.jpg.webp) Beneath the Cards in a Game of Whist (ca. 1882–1886) etching (12.38 x 9.05 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Beneath the Cards in a Game of Whist (ca. 1882–1886) etching (12.38 x 9.05 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Cartoons and caricatures

Félicien Rops was a pioneer and considered by many as the starting point for Belgian Comics. He was the first Belgian cartoonist to produce text comics, a comic strip based on a recurring character, satirical, and erotic comics. Rops began publishing comics in student magazines including Le Crocodile and Le Diable au Salon while still in school in the 1850s. He sometimes published using pseudonyms, including Spor, Risette, Graffin, Cham-Loth, and Croque-tout. With friends he co-founded a weekly artistic and literary satirical review The Uylenspiegel in 1856, which he contributed to regularly until its demise 1862. Examples of the early use of text comics and reoccurring characters include Les époux Van-Blague, the comedic experiences of a couple published in Le Crocodile (e.g. issue #40, 20 November 1853) and a series of thematically unified, but otherwise unrelated humorous episodes at the Antwerp Zoo Promenade au Jardin Zoologique. One cartoon in particular, 'La Médaille de Waterloo' (1858), depicting a decrepit, peg legged likeness of Napoléon Bonaparte on a medal, guarded by his devotee's from a hoard of skeletons rising from the dead, (in criticism of those who held Napoléon in honor with seemingly no regard for the havoc and loss of life that he had brought to Europe) caused an outrage in France and Belgium. However, ultimately this only served to further Rops notoriety. Rops published significantly fewer comics as his career as an illustrator of books progressed but, he produced occasional comics, caricatures, even advertisements, throughout his life.[3]

Gallery V: cartoons and caricatures

_lithograph_(30.16_x_22.7_cm)_Los_Angeles_County_Museum_of_Art.tiff.jpg.webp) The White Slave: The Casinos (Uylenspiegel, No. 11, 13 Apr. 1856) lithograph (30.16 x 22.7 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art

The White Slave: The Casinos (Uylenspiegel, No. 11, 13 Apr. 1856) lithograph (30.16 x 22.7 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art_lithograph_(22.54_x_16.03_cm)_Los_Angeles_County_Museum_of_Art.tiff.jpg.webp) Galerie d'Uylenspiegel, Eduoard (Uylenspiegel, no. 5, 2 March 1856) lithograph (22.54 x 16.03 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Galerie d'Uylenspiegel, Eduoard (Uylenspiegel, no. 5, 2 March 1856) lithograph (22.54 x 16.03 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art_lithograph_(20.32_x_17.15_cm)_Los_Angeles_County_Museum_of_Art.tiff.jpg.webp) Jardin Zoologique (Uylenspiegel, no. 20, 15 June 1856) lithograph (20.32 x 17.15 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Jardin Zoologique (Uylenspiegel, no. 20, 15 June 1856) lithograph (20.32 x 17.15 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art_lithograph)_(28.58_x_20.64_cm)_Los_Angeles_County_Museum_of_Art.tiff.jpg.webp) Jardin Zoologique (Uylenspiegel, no. 28, 9 August 1857) lithograph) (28.58 x 20.64 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Jardin Zoologique (Uylenspiegel, no. 28, 9 August 1857) lithograph) (28.58 x 20.64 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art Louis Defré (aka Maurice Voituron & Joseph Boniface), burgomaster of Uccle (1858) lithograph (28.58 x 19.53 cm) L.A. County Museum.

Louis Defré (aka Maurice Voituron & Joseph Boniface), burgomaster of Uccle (1858) lithograph (28.58 x 19.53 cm) L.A. County Museum._lithograph_(58.2_x_43.6_cm)_Michael_C._Carlos_Museum%252C_Emory_University%252C_Atlanta.jpg.webp) Médaille de Waterloo (1858) lithograph (58.2 x 43.6 cm) Michael C. Carlos Museum, Emory University, Atlanta

Médaille de Waterloo (1858) lithograph (58.2 x 43.6 cm) Michael C. Carlos Museum, Emory University, Atlanta_lithograph_(23.65_x_18.89_cm)_Los_Angeles_County_Museum_of_Art_of_Art.tiff.jpg.webp) Political Comedy (1859) lithograph (23.65 x 18.89 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art of Art

Political Comedy (1859) lithograph (23.65 x 18.89 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art of Art_lithograph_(23.65_x_20_cm)_Los_Angeles_County_Museum_of_Art.tiff.jpg.webp) Constitutional Chronicles (no date) lithograph (23.65 x 20 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Constitutional Chronicles (no date) lithograph (23.65 x 20 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art_lithograph_(29.53_x_22.07_cm)_Los_Angeles_County_Museum.tiff.jpg.webp) The Last Incarnation of Vautrin (Uylenspiegel, No. 39, 2 Nov. 1862) lithograph (29.53 x 22.07 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art

The Last Incarnation of Vautrin (Uylenspiegel, No. 39, 2 Nov. 1862) lithograph (29.53 x 22.07 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art Order Reigns in Warsaw (1863) lithograph (36.4 x 29.7)

Order Reigns in Warsaw (1863) lithograph (36.4 x 29.7)_etching_(ca._7.94_x_10.6_cm)_Los_Angeles_County_Museum_of_Art.jpg.webp) The Right to Rest, The Right to Work (ca. 1868) etching (ca. 7.94 x 10.6 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art

The Right to Rest, The Right to Work (ca. 1868) etching (ca. 7.94 x 10.6 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art_etching_on_Japan_paper_(19.37_x_15.08_cm)_Los_Angeles_County_Museum_of_Art.tiff.jpg.webp) Misanthropie! (1872) etching on Japan paper (19.37 x 15.08 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Misanthropie! (1872) etching on Japan paper (19.37 x 15.08 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Artwood_engraving_(34.7_x_27.15_cm)_Los_Angeles_County_Museum_of_Art.tiff.jpg.webp) Parisian Life (1876) wood engraving (34.7 x 27.15 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Parisian Life (1876) wood engraving (34.7 x 27.15 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art_etching_(7.62_x_5.56_cm)_Los_Angeles_County_Museum_of_Art_I.jpg.webp) Duluc Sisters, Dresses (no date) etching (7.62 x 5.56 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art I

Duluc Sisters, Dresses (no date) etching (7.62 x 5.56 cm) Los Angeles County Museum of Art I

References

- Robert L. Delevoy (1978) Symbolists and Symbolism. Skira/Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., New York, 247 pp.

- Jean Cassou (1979) The Concise Encyclopedia of Symbolism. Chartwell Books, Inc., Secaucus, New Jersey, 292 pp. [48, 94, 130-131 pp.]

- Lambiek Comiclopedia: Félicien Rops. Entry by Kjell Knudde. https://www.lambiek.net/artists/r/rops_felicien.htm

- Patrick Bade (2003) Félicien Rops. Parkstone Press Ltd, New York, 95 pp.

- Lee Revens and J.-K. Huysmans (1975) The Graphic Work of Félicien Rops. Léon Amiel Publisher, New York. 288 pp. [8-11 pp.]

- Hoffmann, Edith, "Rops, Félicien", Oxford Art Online

- Rops, Félicien, and Brison, Charles (1969). Pornocrates: an introduction to the life and work of Felicien Rops, 1833–1898. Skilton. p. 10.

- Félicien Rops Biography. Musée Félicien Rops, Province de Numar. Accessed 12 September 2019 https://www.museerops.be/biographie

- Claude Pichois (1989) Baudelaire. Hamish Hamilton Ltd. (The Penguin Group, London). ISBN 0241 124581

- Lois Boe Hyslop and Francis E. Hyslop, Jr. (1957) Baudelaire: A Self-Portrait. Oxford University Press, London.

- Félicien Rops, Baudelaire and skeleton passions. British Library, European Studies Blog, 27 October 2014. Accessed 12 September 2019 https://blogs.bl.uk/european/2014/10/f%C3%A9licien-rops-baudelaire-and-skeleton-passions.html

- Georges Poulet (1969) Who was Baudelaire? Editions d'Art Albert Skira, Geneva. 188 pp.

- Paul Adam, Jean Moréas, and Félix Fénéon (1886) Petit Bottin de Letters et des Arts. E. Giraud & Co., Paris.

- "Rops, Félicien". 21 March 2008. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- Huysmans, J-K. L’au-delà du mal ou l’oeuvre érotique de Félicien Rops. La Plume, No. 172: 15 juin 1896, p. 388-401.

- Grand Orient du Belgiqua http://gob.be/ accessed 26 September 2019

- Per Faxneld (2017). Satanic Feminism: Lucifer as the Liberator of Woman in Nineteenth-Century (Oxford Studies in Western Esotericism). Oxford University Press, New York, 576 pp.[286 p.] eISBN 978-0-19-066449-7

- Blakeley, H. R. (2015) Beyond Eros: Works by Félicien Rops in the Michael C. Carlos Museum. Carlos Museum and Emory’s Center for Digital Scholarship, Emory University, Atlanta. Accessed 23 September 2019 https://rops.digitalscholarship.emory.edu/exhibits/show/felicien-rops

- Encyclopaedia Britannica (2019) Félicien Rops, Belgian Artist. (last update: 18 Aug 2019) accessed 16 October 2019

- Thomson, Richard (2000). Felicien Rops, Rops-suis-aultre-ne-veult-estre.". Print Quarterly 17(4): 427–429.

- Jean-Luc Daval (1979) Modern Art: The Decisive Years 1884–1914. Skira/Rizzoli International publications, Inc., New York. 221 pp. ISBN 0-8478-0212-4

- The Editors of Réalités under the direction of Jean Clay (1973) Impressionism. Chartwell Books Inc., Secaucus, 320 pp. [page 56] ISBN 0-399-11039-9

- Blunden, Maria; Blunden, Godfrey; Daval, Jean-Luc (1976). Impressionists and Impressionism. New York: Skira/Rizzoli International Publication, Inc. p. 239. ISBN 0-8478-0047-4.

- Ward, Gerald W. R. (2007). The Grove Encyclopedia of Materials and Techniques in Art. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 828. ISBN 978-0-19-531391-8.

- Josef von Sternberg, (1966) Fun in a Chinese Laundry. Martin Secker & Warburg Ltd, London, 348.[231-232 pp.]

- Uhr, Horst (1990) Lovis Corinth. University of California Press, Berkeley, 347 pp. ISBN 0-520-06776-2

- Farmer, John David (1976). Ensor. New York: George Braziller, Inc. pp. 49 pp. + 79 pages of plates. ISBN 0-8076-0840-8.

- Hoberg, Annegret (2008) Alfred Kubin: Drawings 1897–1909. Neue Galerie, New York/Prestel Verlag, Munich. 230 p. ISBN 978-3-7913-4094-4

- Alric Delaporte (2014) Les Diaboliques de Félicien Rops. Master Thesis, University of Paris, Panthéon-Sorbonne. https://hicsa.univ-paris1.fr/documents/file/JE%20Meneux%20Master%202014/3-Delaporte-Diaboliques%20Rops.pdf

- Nicolas Valazza (with S. N. Rosenberg, L. Lerme & H. (2019) Banned Books and Prints in Europe and the United States, 17th–20th Centuries. Works from the Lilly Library and the Kinsey Institute Collections. Indiana University Bloomington https://bannedbooks.indiana.edu/exhibits/show/bannedbooks/prose--france--19th-century

- Arne Eggum (1978) Edvard Munch: Symbols and Images. National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. 264 pp.

- Przybyszewski, Stanislaw, editor (1894). Das Werk des Edvard Munch. Published by S. Fischer Verlag, Berlin. With contributions by Stanislaw Przybyszewski, Franz Servaes, Willy Pastor, Julius Meier-Graefe.

- Messer, Thomas M. (1970). Munch: The Library of Great Painters. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers, New York. 166 pp. [page 35]

- Prelinger, Elizabeth and Michael Parke-Taylor(1996). The Symbolist Prints of Edvard Munch. Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 236 pp.

Further reading

- P. & V. Berko, "Dictionary of Belgian painters born between 1750 & 1875", Knokke 1981, p. 565–566.

- P. & V. Berko, "19th Century European Virtuoso Painters", Knokke 2011, p. 513, illustrations p. 145.

External links

- The Musée Félicien Rops in Namur (English, French)

- Rops correspondence at Mount Holyoke College Archived 13 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Works by Félicien Rops at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Félicien Rops at Internet Archive

- Felicien Rops at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Blakeley, H. R. (2015) Beyond Eros: Works by Félicien Rops in the Michael C. Carlos Museum. Carlos Museum and Emory's Center for Digital Scholarship, Emory University, Atlanta. Accessed 23 September 2019 Beyond Eros: Works by Félicien Rops in the Michael C. Carlos Museum · Félicien Rops

- Félicien Rops Letters,

- Musée Félicien Rops [Félicien Rops Museum] Musée Félicien Rops – Musée d'Art du 19e – à Namur

- Bienvenue au château de Thozée! - Welcome to Château de Thozée! (Accessed 30 December 2019)

- Church of Saint-Loup at Namur. Wikimedia Commons, Category: Église Saint-Loup, Namur (Accessed 30 December 2019)