Fanqie

Fanqie (Chinese: 反切; pinyin: fǎnqiè; lit. 'reverse cut') is a method in traditional Chinese lexicography to indicate the pronunciation of a monosyllabic character by using two other characters, one with the same initial consonant as the desired syllable and one with the same rest of the syllable (the final). The method was introduced in the 3rd century AD and is to some extent still used in commentaries on the classics and dictionaries.

| Fanqie | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 反切 | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese | phiên thiết | ||||||||||||||||||

| Chữ Hán | 反切 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 반절 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 反切 | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 反切 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Hiragana | はんせつ | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

History

Early dictionaries such as the Erya (3rd century BC) indicated the pronunciation of a character by the dúruò (讀若, "read as") method, giving another character with the same pronunciation.[1] The introduction of Buddhism to China around the 1st century brought Indian phonetic knowledge, which may have inspired the idea of fanqie.[1] According to the 6th-century scholar Yan Zhitui, fanqie were first used by Sun Yan (孫炎), of the state of Wei during the Three Kingdoms period (220–280 AD), in his Erya Yinyi (爾雅音義, "Sounds and Meanings of Erya").[1][2] However, earlier examples have been found in the late-2nd-century works of Fu Qian and Ying Shao.[3][4]

The oldest extant sources of significant bodies of fanqie are fragments of the original Yupian (544 AD) found in Japan and the Jingdian Shiwen, a commentary on the classics that was written in 583 AD.[5][6] The method was used throughout the Qieyun, a Chinese rhyme dictionary published in 601 AD during the Sui dynasty.[2][7] When Classical Chinese poetry flowered during the Tang dynasty, the Qieyun became the authoritative source for literary pronunciations. Several revisions and enlargements were produced, the most important of which was the Guangyun (1007–1008). Even after the more sophisticated rime table analysis was developed, fanqie continued to be used in dictionaries, including the voluminous Kangxi Dictionary, published in 1716, and the Ciyuan and Cihai of the 1930s.[8][9]

During the Qing dynasty, some bilingual Chinese-Manchu dictionaries had the Manchu words phonetically transcribed with Chinese characters. The book 御製增訂清文鑑 ("Imperially Published Revised and Enlarged Mirror of Qing"), in both Manchu and Chinese, used Manchu script to transcribe Chinese words and Chinese characters to transcribe Manchu words by using fanqie.[10]

Function

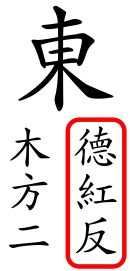

In the fanqie method, a character's pronunciation is represented by two other characters. The onset (initial consonant) is represented by that of the first of the two characters (上字 "upper word", as Chinese was written vertically); the final (including the medial glide, the nuclear vowel and the coda) and the tone are represented by those of the second of the two characters (下字, "lower word").[2][11] For example, in the Qieyun, the character 東 is described by the formula 德紅反. The first two characters indicate the onset and the final, respectively, and so the pronunciation of 東 [tuŋ] is given as the onset [t] of 德 [tək] with the final [uŋ] of 紅 [ɣuŋ],[12] with the same tone as 紅.

In the rhyme dictionaries, there was a tendency to choose pairs of characters that agree on the presence or absence of a palatal medial -j-, but there was no such tendency for the rounded medial -w-, which was represented solely in the final character.[13] There was also a strong tendency to spell words with labial initials using final characters with labial initials.[14]

The third character 反 fǎn "turn back" is the usual marker of a fanqie spelling in the Qieyun. In later dictionaries such as the Guangyun, the marker character is 切 qiè "run together". (The commonly-cited reading "cut" seems to be modern.[3]) The Qing scholar Gu Yanwu suggested that fǎn, which also meant "overthrow", was avoided after the devastating rebellions during the middle of the Tang dynasty.[3] The origin of both terms is obscure.[15] The compound word fǎnqiè first appeared during the Song dynasty.[3]

Analysis

Fanqie provide information about the sounds of earlier forms of Chinese, but its recovery is not straightforward. Several characters could be used for each initial or final, and in particular, no character was ever used to spell itself.

However, it is possible to identify the initials and the finals underlying a large and consistent collection of fanqie by using a method that was first used by the Cantonese scholar Chen Li, in his 1842 study of the Guangyun.[16] For example, in that dictionary,

- 東 was spelled 德 + 紅,

- 德 was spelled 多 + 特, and

- 多 was spelled 德 + 河.

That implies that 東, 德 and 多 must all have had the same initial.[17] By following such chains of equivalence, Chen was able to identify categories of equivalent initial spellers, and a similar process was possible for the finals.[16][18] Unaware of Chen's work, the Swedish linguist Bernard Karlgren repeated the analysis to identify the initials and finals in the 1910s.[19]

Chen's method can be used to identify the categories of initials and finals, but not their sound values, for which other evidence is required.[16] Thus, Middle Chinese has been reconstructed by Karlgren and later scholars by comparing those categories with Sino-Xenic pronunciations and the pronunciations in modern varieties of Chinese.[20]

Effects of sound change

The method described the pronunciations of characters in Middle Chinese, but the relationships have been obscured as the language evolved into the modern varieties over the last millennium and a half. Middle Chinese had four tones, and initial plosives and affricates could be voiced, aspirated or voiceless unaspirated. Syllables with voiced initials tended to be pronounced with a lower pitch, and by the late Tang dynasty, each of the tones had split into two registers (traditionally known as yīn 陰 and yáng 陽) conditioned by the initials. Voicing then disappeared in all dialects except the Wu group, with consonants becoming aspirated or unaspirated depending on the tone. The tones then underwent further mergers in various varieties of Chinese. Thus, the changes in both the initial and the tone were conditioned on each other, as represented by different characters in the fanqie pair.[21]

For example, the characters of formula 東 [tuŋ] = 德 [tək] + 紅 [ɣuŋ] are pronounced dōng, dé and hóng in modern Standard Chinese; thus, the tones no longer match. That is because the voiceless initial [t] and the voiced initial [ɣ] condition different registers of the Middle Chinese level tone, yielding the first and the second tones of the modern language. (The pinyin letter d represents the voiceless and unaspirated stop [t].)

That effect sometimes led to a form of spelling pronunciation. Chao Yuen Ren cited the example of the character 强, which had two readings in Middle Chinese. It could be read as [ɡjɑnɡ] in the level tone, meaning "strong, powerful", which developed regularly into the modern reading qiáng. However, it could be read also as [ɡjɑnɡ] in the rising tone, meaning "stubborn" or "forced". The regular development would be for the voiced initial [ɡ] to condition the yang register of the rising tone, becoming the fourth tone of modern Chinese and for the rising tone to condition an unaspirated initial. Thus, jiàng would be expected, and this does occur in the sense "stubborn", but the character also has the unexpected pronunciation qiǎng for the sense "forced". Chao attributed that to the fanqie formula 强 = 其 [ɡi] (level tone) + 兩 [ljɑnɡ] (rising tone) given in dictionaries. Here, the first character is now pronounced qí because in the level tone, the voiced initial becomes aspirated, but the second character is now pronounced liǎng. That is because in the rising tone, sonorants like [l] conditioned the yin register, which led to the modern third tone.[8]

Use in Cantonese

In Cantonese, fanqie can be found in some dictionaries to this day, often alongside other romanization system or phonetic guides, to indicate the pronunciation of characters lacking a homophone.

For example, in the Sun Ya dictionary the character 攀 is transcribed as pinyin pān and for Cantonese pan¹ and the Cantonese tonal homophone 扳 , whereas 戀, lacking a tonal homophone, is transcribed as lyn² and 〔拉婉切〕 (l-āai + yún) to give lyún.[22] If there is no tonal homophone, the tone is indicated. For example 實用廣州話分類詞典 transcribes 仆 as [pʰok⁶] and fanqie 〔披屋切〕 (p-ēi + ūk) but 𠵿, lacking a tonal homophone is transcribed as [pʰɛ¹] and 〔音披爺切第1聲〕, i.e. p-ēi + y-èh with tone 1 to give pē.[23]

See also

References

- Casacchia (2006), p. 359.

- Chu (1990).

- Branner (2000), p. 38.

- Pulleyblank (1999), p. 105.

- Pulleyblank (1984), p. 144.

- Baxter (1992), p. 40.

- Casacchia (2006), p. 360.

- Chao (1961), p. 173.

- Yong & Peng (2008), p. 39.

- Yong & Peng (2008), p. 397.

- Casacchia (2006), pp. 359–360.

- Wang (1980).

- Chao (1941), pp. 205–207, 215.

- Chao (1941), pp. 217–218.

- Norman (1988), p. 27.

- Norman (1988), p. 28.

- Baxter & Sagart (2014), p. 10.

- Pulleyblank (1984), pp. 142–143.

- Pulleyblank (1984), p. 142.

- Norman (1988), pp. 34–37.

- Norman (1988), pp. 34–36, 52–54.

- 何容 (1985). 新雅中文字典. Hong Kong: Sun Ya Publications. ISBN 9789620811883.

- 麥耘, 譚步雲 (2018). 實用廣州話分類詞典. Hong Kong: 商務印書館. ISBN 9789620703058.

Works cited

- Baxter, William H. (1992), A Handbook of Old Chinese Phonology, Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-012324-1.

- Baxter, William H.; Sagart, Laurent (2014), Old Chinese: A New Reconstruction, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-994537-5.

- Branner, David Prager (2000), "The Suí–Táng tradition of Fǎnqiè phonology", in Auroux, Sylvain; Koerner, Konrad; Niederehe, Hans-Josef; Versteegh, Kees (eds.), History of the Language Sciences, Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 36–46, ISBN 978-3-11-011103-3.

- Casacchia, G. (2006), "Chinese Linguistic Tradition", in Brown, Keith (ed.), Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics, vol. 2 (2nd ed.), London: Elsevier, pp. 358–362, ISBN 978-0-08-035943-4.

- Chao, Yuen Ren (1941), "Distinctions within Ancient Chinese", Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, 5 (3/4): 203–233, doi:10.2307/2717913, JSTOR 2717913.

- ——— (1961), "What is correct Chinese?", Journal of the American Oriental Society, 81 (3): 171–177, doi:10.2307/595651, JSTOR 595651. Reprinted as Chao, Yuen Ren (1976), "What is correct Chinese?", Aspects of Chinese sociolinguistics: essays by Yuen Ren Chao, Stanford University Press, pp. 72–83, ISBN 978-0-8047-0909-5.

- Chu, Chia-Ning 竺家寧 (1990), Shēngyùn xué 聲韻學 [Phonology], Taipei: 五南圖書. (This book pointed out that use of fanqie appeared as early as Eastern Han.)

- Norman, Jerry (1988), Chinese, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-29653-3.

- Pulleyblank, Edwin G. (1984), Middle Chinese: a study in historical phonology, Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, ISBN 978-0-7748-0192-8.

- ——— (1999), "Chinese traditional phonology", Asia Major, 12 (2): 101–137, JSTOR 41645549.

- Wang, Li (1980), Hànyǔ shǐgǎo 漢語史稿 [History of the Chinese language], ISBN 978-7-101-01553-9.

- Yong, Heming; Peng, Jing (2008), Chinese lexicography: a history from 1046 BC to AD 1911, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-156167-2.