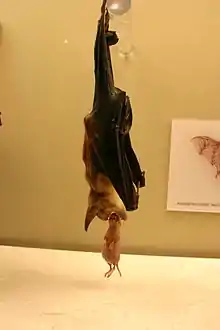

Spectral bat

The spectral bat (Vampyrum spectrum), also called the great false vampire bat, great spectral bat, American false vampire bat or Linnaeus's false vampire bat, is a large, carnivorous leaf-nosed bat found in Mexico, Central America, and South America. It is the only member of the genus Vampyrum; its closest living relative is the big-eared woolly bat. It is the largest bat species in the New World, as well as the largest carnivorous bat: its wingspan is 0.7–1.0 m (2.3–3.3 ft). It has a robust skull and teeth, with which it delivers a powerful bite to kill its prey. Birds are frequent prey items, though it may also consume rodents, insects, and other bats.

| Spectral bat | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Chiroptera |

| Family: | Phyllostomidae |

| Genus: | Vampyrum Rafinesque, 1815 |

| Species: | V. spectrum |

| Binomial name | |

| Vampyrum spectrum | |

.png.webp) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Unlike the majority of bat species, it is monogamous. Colonies consist of an adult male and female and their offspring. The adult male will bring food back to the roost to provision the adult female and their offspring. Colonies generally roost in tree hollows, though individuals may roost in caves. Due to habitat destruction and its low population density, it is listed as a near-threatened species by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Taxonomy and evolution

The spectral bat was described in 1758 by Swedish zoologist Carl Linnaeus. The holotype was collected in South America by Daniel Rolander. Linnaeus assigned it to the genus Vespertilio, which he classified as a kind of primate.[2] Its species name "spectrum" is from Latin meaning "apparition" or "specter".

The genus Vampyrum was not described until 1815 by Constantine Samuel Rafinesque.[3] The genus and species names were not used in their current combination until biologist George Gilbert Goodwin did so in 1942.[4] "Vampyrum" is a Neo-Latin derivative of vampire, thus named because it was once erroneously believed that the species was sanguivorous and consumed blood.[5]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Position of Vampyrum in Phyllostomidae based on molecular data.[6] Tribe relationships based on Hoffmann et al. 2008.[7] |

Based on mitochondrial DNA and the RAG2 gene, the spectral bat is most closely related to the monotypic genus Chrotopterus (the big-eared woolly bat).[6]

Vampyrum and Chroptopterus diverged from other leaf-nosed bat species approximately 20.75 million years ago, with the two genera diverging from each other 14.35 million years ago.[8] The spectral and big-eared woolly bats likely evolved from an insectivorous ancestor.[9]

The spectral bat is included within the subfamily Phyllostominae, which includes species of diverse feeding strategies, including carnivory, insectivory and mixed insectivory/frugivory. The spectral and big-eared woolly bats are the two extant members of the tribe Vampyrini. Vampyrini additionally includes the extinct genus Notonycteris.[7] Based on dental characteristics, Czaplewski and Morgan additionally included the fringe-lipped bat (genus Trachops) and sometimes the round-eared bats (genus Lophostoma) in Vampyrini.[10]

Description

The spectral bat is the largest bat species native to the New World and the largest carnivorous bat in the world.[11] The wingspan typically ranges from 0.7–1.0 m (2.3–3.3 ft). Its forearm length is 101–110 mm (4.0–4.3 in).[4] Its body length is 135–147 mm (5.3–5.8 in) and its mass is 134–189 g (4.7–6.7 oz).[13][14] Its wings, though large in an absolute sense, are short relative to its body size. The wings are wide, though, creating a large surface area. Its wingtips are rounded and almost squarish.[15] The thumbs are long, at 21.4–22.2 mm (0.84–0.87 in).[14] Each of its thumbs has a large, recurved claw that is grooved, similar to those of cats. Its back fur is reddish-brown, long, and soft, while its belly fur is shorter and paler. The forearm is furred on the half closer to the body, but naked on the half closer to the wrist and fingers.

Its molars are narrow with W-shaped crests. While six of its molars have three cusps, as in many mammal species, the last upper molars are reduced to two cusps; they are much smaller than the other molars. The talonids (crushing surfaces) of the molars are small relative to their trigonids (shearing surfaces).[16] The upper canine teeth are well-developed. Its dental formula is 2.1.2.32.1.3.3 for a total of 34 teeth. Its skull is narrow and elongated with a pronounced sagittal crest. Overall, its skull resembles a miniature canid or bear skull.[17] Its nose-leaf is large, at 17 mm (0.67 in) in length. There is no discernible tail,[18] but the uropatagium (tail membrane) is long and broad.[19] Its legs are long, and the feet are composed of slender bones; each digit has a well-developed claw. The ears are large and rounded, at 39–42 mm (1.5–1.7 in) long.

The brain is large relative to the body; at 1:67, its brain-to-body mass ratio is higher than that of cats and dogs.[20][21] The cerebral hemispheres of the brain are extensively convoluted.[22] The brain has well-developed olfactory bulbs and its cerebellum is the most ornamented and complex of any member of its subfamily. McDaniel described its corpus callosum and white matter as "exceptionally thick".[22]

Biology and ecology

Diet

The spectral bat is exclusively carnivorous,[23] consuming birds, rodents, and other species of bat. Additionally, it consumes some insects such as beetles.[24] It preys on other bats opportunistically, and it is known to eat bats out of researchers' mist nets. Prey species include the highland yellow-shouldered bat, Geoffroy's tailless bat, Pallas's long-tongued bat, short-tailed fruit bats, the common vampire bat, and fruit-eating bats[25] It was once thought to supplement its diet with fruit, but a captive pair refused to eat any fruit over a 5-year period.[26] Its diet can be studied passively because it carries prey items back to its roost to consume, discarding unwanted parts such as bird feathers, bat wings, and rodent tails. Over the course of a year, 18 bird species were identified from feathers left under a roost in Costa Rica: based on the assemblage, it prefers non-perching bird species that weigh 20–150 g (0.71–5.29 oz).[27] However, a later study in Brazil determined that perching bird species were a majority of prey items.[24]

Doves and cuckoos are frequently consumed—they represented over half the prey items documented in the Costa Rican study. Some prey species such as cuckoos, trogons, and motmots are known to have a strong odor, leading Vehrencamp et al. to hypothesize that spectral bats may rely on scent to locate prey. It also prefers prey that roost in groups, which may aid in detection. The groove-billed ani, which both has a strong smell and roosts in groups, is a particularly common prey item, representing approximately 24-26 of the 86 prey items identified in the study. Other species identified included the orange-fronted parakeet, orange-chinned parakeet, rufous-naped wren, streak-backed oriole, and scissor-tailed flycatcher. The largest prey species identified was the white-tipped dove, which at 150 g (5.3 oz), weighs almost as much as spectral bats. Because its prey items can be so large, it may only need to consume one bird every two or three nights to meet its caloric requirements. [27]

Foraging

The spectral bat uses echolocation to navigate, creating short pulses of ultrasound at relatively low frequencies; its echolocation characteristics are suited for maneuvering around obstacles while flying low to the ground. Its foraging style has been compared to owls; it likely uses its agile and maneuverable wings to hover as it plucks prey items off the ground or tree branches.[25] It stalks the prey and then lands on it from above, securing the prey by hooking it with its sharp thumb claws.[28] It kills its prey by delivering a forceful bite to the skull.[26] Relative to its size, its bite force is stronger than any Carnivoran.[17] Its bite force is predicted to measure 80–100 Newtons based on its body size and canine teeth characteristics.[29] It has been recorded as being attracted to the distress calls of smaller bats while hunting.[30]

In a study of the wing morphology of 51 Neotropical bat species, the spectral bat had the lowest wing loading (body mass to wing area ratio) at 20.05.[15] Low wing loading is advantageous for carnivorous bats because it allows them to pick up prey items from the ground and fly with them.[31] Its wing structure allows it to take flight in confined spaces and to carry heavy prey items, despite the bat's size. Males will carry prey back to their roosts to provision females and their pup.[27]

Reproduction and life cycle

The spectral bat is one of an estimated 18 species of bat which are monogamous. Additionally, it is one of two known species of bat where the males provide parental care, the other being the yellow-winged bat.[32] Males have relatively small testes—as a monogamous species, there is not generally sperm competition, so males can save energy by producing less sperm.[33]

It is a seasonal breeder, with females giving birth at the end of the dry season or the beginning of the rainy season. The litter size is one individual, with offspring called "pups."[34] The mother is reportedly very attentive and gentle with her offspring. The male is often in attendance as well and will frequently sleep with both the female and their young completely wrapped up in his wings.[26] The extent of natural depredation upon spectral bats is unknown, but spectral bat remains were once documented in a western barn owl pellet in Oaxaca, Mexico.[35]

Spectral bats roost independently or in small colonies of up to five individuals in hollow trees. An examination of one colony of five individuals consisted of an adult male and female, a nursing pup, and a juvenile male and female. The juvenile male was estimated to be six months old; he was presumed to be the older offspring of the adults, while the female was also possibly their offspring.[27] Though it was initially believed to only roost in trees, it was first documented using a cave as a roost in 2008. Its average lifespan is unknown; however, it is believed that the same individual roosted in a cave from 2008 until at least 2016 based on a unique ear pigmentation, making lifespans of at least 8 years possible. In captivity, one adult individual of uncertain initial age was maintained for 5.5 years.[36]

Range and habitat

The spectral bat is found in Belize, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, French Guiana, Guatemala, Guyana, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Peru, Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago, and Venezuela.[1] It has been documented at elevations from 0–1,650 m (0–5,413 ft) above sea level, though in Mexico it is only found in lowland areas of below 150 m (490 ft). It is associated with tropical rainforests.[19] In 2010, the species was documented for the first time in the Cerrado of Brazil.[37] It is occasionally encountered in pastures and orchards.[1]

Conservation

As of 2018, the spectral bat is classified as near threatened by the IUCN. Its population size is difficult to assess, as it is rarely encountered. However, its population trend is assessed as decreasing.[1] It may be intentionally persecuted by humans. In Trinidad, the bats are sometimes thought to be ghosts, and locals will seek out and destroy their roosts.[38]

As of 1999, the spectral bat is listed as endangered in Bolivia.[39] It has been listed as an endangered species in Mexico since 2001.[1]

References

- Solari, S. (2018). "Vampyrum spectrum". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T22843A22059426. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22843A22059426.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- Linnæus, Carl (1758). Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I [By means of the three kingdoms of nature, the nature of the system, according to the classes, ordines, genera, species, with the characters, the differences, synonyms, places.] (in Latin) (10th ed.). Holmiæ: Laurentius Salvius. p. 31. Retrieved 21 November 2012.

- Rafinesque, C. (1815). Analyse de la nature, ou tableau de l'univers et des corps organisés [Analysis of nature, or picture of the universe and organized bodies] (in French). Vol. 1815. Palerme :Aux dépens de l'auteur, 1815. p. 54.

- Gardner, A. L. (2008). Mammals of South America, Volume 1: Marsupials, Xenarthrans, Shrews, and Bats. Vol. 1. University of Chicago Press. pp. 299–300. ISBN 978-0226282428.

- Husson, A. M. (1978). The mammals of Suriname. Vol. 2. Brill Archive. pp. 107–108. ISBN 978-9004058194.

- Monteiro, Leandro R; Nogueira, Marcelo R (2010). "Adaptive Radiations, Ecological Specialization, and the Evolutionary Integration of Complex Morphological Structures". Evolution. 64 (3): 724–44. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00857.x. PMID 19804403.

- Hoffmann, Federico G; Hoofer, Steven R; Baker, Robert J (2008). "Molecular dating of the diversification of Phyllostominae bats based on nuclear and mitochondrial DNA sequences". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 49 (2): 653–8. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2008.08.002. PMID 18727956.

- Baker, Robert J; Bininda-Emonds, Olaf R. P; Mantilla-Meluk, Hugo; Porter, Calvin A; Van Den Bussche, Ronald A (2012). "Molecular time scale of diversification of feeding strategy and morphology in New World Leaf-Nosed Bats (Phyllostomidae): a phylogenetic perspective". Evolutionary History of Bats. p. 385. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139045599.012. ISBN 9781139045599.

- Monteiro, Leandro R; Nogueira, Marcelo R (2011). "Evolutionary patterns and processes in the radiation of phyllostomid bats". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 11: 137. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-11-137. PMC 3130678. PMID 21605452.

- Czaplewski, Nicholas J; Morgan, Gary S (2012). "New basal noctilionoid bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera) from the Oligocene of subtropical North America". Evolutionary History of Bats. p. 162. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139045599.006. ISBN 9781139045599.

- Nuwer, Rachel (10 May 2016). "The World's Carnivorous Bats Are Emerging From the Dark". Smithsonian.com. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- Simmons, N. B.; Voss, R. S. (1998). "The mammals of Paracou, French Guiana, a Neotropical lowland rainforest fauna. Part 1, Bats". Bulletin of the AMNH (237). hdl:2246/1634.

- da Silva, A. P.; Rossi, R. V. (2011). "New records of Vampyrum spectrum (Chiroptera, Phyllostomidae) for the Pantanal domain in Brazil, with notes on the species natural history, biometry, and lower incisors arrangement". Chiroptera Neotropical. 17 (1): 836–841.

- Marinello, M.M; Bernard, E (2014). "Wing morphology of Neotropical bats: A quantitative and qualitative analysis with implications for habitat use". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 92 (2): 141. doi:10.1139/cjz-2013-0127.

- Freeman, Patricia W (1984). "Functional cranial analysis of large animalivorous bats (Microchiroptera)". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 21 (4): 387–408. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.1984.tb01601.x. S2CID 37499533.

- Santana, Sharlene E; Cheung, Elena (2016). "Go big or go fish: Morphological specializations in carnivorous bats". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 283 (1830): 20160615. doi:10.1098/rspb.2016.0615. PMC 4874722. PMID 27170718.

- The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. "False vampire bat". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- Medellín, R. (2014). Ceballos, G. (ed.). Mammals of Mexico. JHU Press. pp. 694–696. ISBN 978-1421408439.

- Bhatnagar, Kunwar P; Smith, Timothy D; Rai, Shesh N; Frahm, Heiko D (2016). "The Chiropteran Brain Database: Volumetric Survey of the Hypophysis in 165 Species". The Anatomical Record. 299 (4): 492–510. doi:10.1002/ar.23321. PMID 26800031.

- "Measuring Brain Size versus Body Size". Serendip Studio. Serendip. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- McDaniel, V. R. (1976). "Brain anatomy". In Baker, R. J.; Jones Jr., JK; Carter, DC (eds.). Biology of bats of the New World family Phyllostomatidae Part I. pp. 147–200.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Giannini, Norberto P.; Kalko, Elisabeth K. V. (2005). "The guild structure of animalivorous leaf-nosed bats of Barro Colorado Island, Panama, revisited". Acta Chiropterologica. 7 (1): 136. doi:10.3161/1733-5329(2005)7[131:TGSOAL]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 85309649.

- Bonato, Vinícius; Gomes Facure, Kátia; Uieda, Wilson (2004). "Food Habits of Bats of Subfamily Vampyrinae in Brazil". Journal of Mammalogy. 85 (4): 708. doi:10.1644/BWG-121.

- Peterson, R. L; Kirmse, Peter (1969). "Notes on Vampyrum spectrum, the false vampire bat, in Panama". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 47: 140–142. doi:10.1139/z69-025.

- Greenhall, Arthur M (1968). "Notes on the Behavior of the False Vampire Bat". Journal of Mammalogy. 49 (2): 337–340. doi:10.2307/1378008. JSTOR 1378008.

- Vehrencamp, S. L; Stiles, F. G; Bradbury, J. W (1977). "Observations on the Foraging Behavior and Avian Prey of the Neotropical Carnivorous Bat, Vampyrum spectrum". Journal of Mammalogy. 58 (4): 469. doi:10.2307/1379995. JSTOR 1379995.

- Morell, Virginia (July 2018). "Ancient Temple Reveals Secrets of Mexico's Meat-Eating Bats". National Geographic. National Geographic Society. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- Freeman, P. W.; Lemen, C. A. (2009). "Puncture‐Resistance of Gloves for Handling Bats". The Journal of Wildlife Management. 73 (7): 1251–1254. doi:10.2193/2008-295. S2CID 15877222.

- Reid, F. (2009). A field guide to the mammals of Central America and Southeast Mexico. Oxford University Press. pp. 104–105. ISBN 978-0195343229.

- Norberg, U. M; Rayner, J. M. V (1987). "Ecological Morphology and Flight in Bats (Mammalia; Chiroptera): Wing Adaptations, Flight Performance, Foraging Strategy and Echolocation". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 316 (1179): 335. Bibcode:1987RSPTB.316..335N. doi:10.1098/rstb.1987.0030.

- Crichton, E. G.; Krutzsch, P. H. (2000). Reproductive biology of bats. Academic Press. pp. 355–356. ISBN 978-0080540535.

- Adams, Danielle M.; Nicolay, Christopher; Wilkinson, Gerald S. "Patterns of sexual dimorphism and mating systems" (PDF). In Fleming, T. H.; Davalos, L.; Mello, M. (eds.). Phyllostomid bats, a unique mammalian radiation. Chicago University Press.

- Hayssen, Virginia; Ari van Tienhoven & Ans van Tienhoven (1993). Asdell's Patterns of Mammalian Reproduction: a Compendium of Species-specific Data. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-1753-5.

- Santos-Moreno, A.; Alfaro Espinosa, A. M. (2009). "Mammalian prey of barn owl (Tyto alba) in southeastern Oaxaca, México". Acta Zoológica Mexicana. 25 (1).

- Dinets, Vladimir (2017). "Long-term cave roosting in the spectral bat (Vampyrum spectrum)". Mammalia. 81 (5). doi:10.1515/mammalia-2016-0038. S2CID 89446862.

- Sousa, Ricardo Firmino de; Kreutz, Carlos; Oliveira, Sérgio Lopes de; Faria, Karina De Cassia (2011). "Mammalia, Chiroptera, Phyllostomidae, Vampyrum spectrum (Linnaeus, 1758): First record for the Cerrado biome in the state of Mato Grosso, west central Brazil". Check List. 7 (4): 468. doi:10.15560/7.4.468.

- French, Barbara (1997). "False Vampires and Other Carnivores". batcon.org. Bat Conservation International. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- Vargas Espinoza, A.; Aguirre, L. F.; Swarner, M.; Emmons, L.; Teran, M. (2004). "Distribución de Vampyrum spectrum en Bolivia y comentarios sobre su estado de conservación" [Distribution of Vampyrum spectrum in Bolivia and comments on its state of conservation]. Ecología en Bolivia (in Spanish). 39 (2): 46–51.

External links

- Video on YouTube: Biologist Rodrigo Medellín displaying a live spectral bat and describing it (in Spanish with English subtitles)