Iron(II)

In chemistry, iron(II) refers to the element iron in its +2 oxidation state. In ionic compounds (salts), such an atom may occur as a separate cation (positive ion) denoted by Fe2+.

_oxide.jpg.webp)

-chlorid-Tetrahydrat.jpg.webp)

The adjective ferrous or the prefix ferro- is often used to specify such compounds — as in "ferrous chloride" for iron(II) chloride, FeCl2. The adjective "ferric" is used instead for iron(III) salts, containing the cation or Fe3+. The word ferrous is derived from the Latin word ferrum for iron.

Iron(II) atoms may also occur as coordination complexes, such as the polymer iron(II) oxalate dihydrate, [Fe(C2O4)(H2O)2]n or [Fe2+][C2O2−4][H2O]2n; and organometallic compounds, such as the neutral molecule ferrocene, Fe(C2H5)2 or [Fe2+][C5H−5]2.

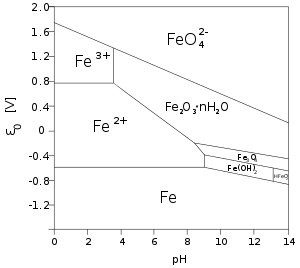

Iron is almost always encountered in the oxidation states 0 (as in the metal), +2, or +3. Solid iron(II) salts are relatively stable in air, but in the presence of air and water they tend to oxidize to iron(III) salts that include hydroxide (HO−) or oxide (O2−) anions.

Iron(II) and life

All known forms of life require iron. Many proteins in living beings contain bound iron ions; those are an important subclass of the metalloproteins. Examples include hemoglobin, ferredoxin, and the cytochromes.

These proteins perform their vital functions thanks to the relatively easy switching of the iron atom between the +2 and +3 states. Hemoglobin, for example, carries oxygen in the blood by binding one molecule O2 to the iron atom, forming oxyhemoglobin. In the process, the iron(II) core of hemoglobin loses an electron to become iron(III), while the oxygen molecule is turned into the superoxide anion O−2.[1]

Insufficient iron in the human diet causes anemia. Animals and humans can obtain the necessary iron from foods that contain it in assimilable form, such as meat. Other organisms must obtain their iron from the environment. However, iron tends to form highly insoluble iron(III) oxides/hydroxides in aerobic oxygenated environments, especially in calcareous soils. Plants (except grasses) solve that problem by encouraging the growth around their roots of certain bacteria that reduce iron(III) to soluble iron(II). (Bacteria and grasses instead secrete compounds called siderophores that form soluble complexes with iron(III).)[2][3][4]

For the same reason, iron is very scarce in seawater, and is often the limiting factor to the growth of the microscopic plants (phytoplankton) that are the basis of the marine food web. This fact was dramatically demonstrated by an experiment where a large area of the ocean surface was sprayed with soluble iron(II) salts, specifically iron(II) sulfate. After several days, the phytoplankton within the treated area bloomed to such an extent that the effect was visible from outer space. This fertilizing process has been proposed as a means to mitigate the carbon dioxide content of the atmosphere.[5]

Iron(II) in solution

Many iron(II) salts are soluble in water, such as iron(II) chloride FeCl2 and iron(II) sulfate FeSO4. Unlike their iron(III) counterparts, these salts dissolve in pure water without significant hydrolysis, and without affecting the pH [6]

When metallic iron (oxidation state 0) is placed in a solution of hydrochloric acid, iron(II) chloride is formed, with release of hydrogen gas, by the reaction

- Fe0 + 2 H+ → Fe2+ + H2

Iron metal is more electropositive than copper, and therefore will displace it from its salts:

- Fe0 + Cu2+ → Fe2+ +Cu0

When iron metal is exposed to air and water, usually it turns into rust, a mixture of oxides and oxide-hydroxides. However, in some environments the metal forms a mixed iron(II) and iron(III) salt with hydroxide and other anions, called green rust.

Complexes

Iron(II) is a d6 center, meaning that the atom has six "valence" electrons in the 3d orbital shell. The 3d, 4s and 4p valence orbitals can therefore accept at most 12 electrons from a great variety of ligands to form coordination complexes and organometallic compounds. Examples include ferrocene and the ferrocyanide ion.

References

- Berg, Jeremy Mark; Lippard, Stephen J. (1994). Principles of bioinorganic chemistry. Sausalito, Calif: University Science Books. ISBN 0-935702-73-3.

- Johanna V. Weiss, David Emerson, Stephanie M. Backer, and J. Patrick Megonigal (2003): "Enumeration of Fe(II)-oxidizing and Fe(III)-reducing bacteria in the root zone of wetland plants: Implications for a rhizosphere iron cycle". Biogeochemistry, volume 64, issue 1, pages 77–96. doi:10.1023/A:102495302

- H. Marschner and V. Römheld (1994): "Strategies of plants for acquisition of iron". Plant and Soil, volume 165, issue 2, pages 261–274. doi:10.1007/BF00008069

- Takanori Kobayashi and Naoko K. Nishizawa (2012): "Iron Uptake, Translocation, and Regulation in Higher Plants". Annual Review of Plant Biology, volume 63, pages 131-152. doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105522

- Boyd PW, Watson AJ, Law CS, et al. (October 2000). "A mesoscale phytoplankton bloom in the polar Southern Ocean stimulated by iron fertilization". Nature. 407 (6805): 695–702. Bibcode:2000Natur.407..695B. doi:10.1038/35037500. PMID 11048709. S2CID 4368261.

- Earnshaw, A.; Greenwood, N. N. (1997). Chemistry of the elements (2nd ed.). Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 0-7506-3365-4.