Crestwood Publications

Crestwood Publications, also known as Feature Publications, was a magazine publisher that also published comic books from the 1940s through the 1960s. Its title Prize Comics contained what is considered the first ongoing horror comic-book feature, Dick Briefer's "Frankenstein". Crestwood is best known for its Prize Group imprint,[1] published in the late 1940s to mid-1950s through packagers Joe Simon and Jack Kirby, who created such historically prominent titles as the horror comic Black Magic, the creator-owned superhero satire Fighting American, and the first romance comic title, Young Romance.

| |

| Founded | 1940 |

|---|---|

| Defunct | 1968 |

| Country of origin | United States |

| Headquarters location | New York City |

| Key people | Teddy Epstein, Mike Bleier, Joe Simon, Jack Kirby |

| Publication types | Comic books, magazines |

| Fiction genres | Romance, Horror, Superhero, Westerns |

| Imprints | Prize Group |

For much of its history, Crestwood's publishers were Teddy Epstein and Mike Bleier. In the 1940s the company's general manager was Maurice Rosenfeld,[2] and in the 1950s the general manager was M.R. Reese.[3] In the mid-1950s, the company office manager was Nevin Fidler (who later became Simon & Kirby's business manager).

In addition to Simon and Kirby, notable Crestwood/Prize contributors included Leonard Starr, Mort Meskin, John Prentice, Joe Maneely, John Severin, Will Elder, Carmine Infantino, Bruno Premiani, Dick Ayers, George Klein, Jack Abel, Ed Winiarski, and Dick Briefer.

History

Origins: Prize Comics

In 1940, Crestwood's Prize Publications, already established as a producer of pulp magazines, jumped onto the superhero bandwagon with the new title Prize Comics. The first issue (March 1940) featured the non-superpowered, costumed crime fighter K the Unknown, whose name was changed to the Black Owl in issue #2 (April 1940).

In Prize Comics #7 (December 1940), writer-artist Dick Briefer introduced the eight-page feature "New Adventures of Frankenstein", an updated version of 19th-century novelist Mary Shelley's much-adapted Frankenstein monster.[4] Considered by comics historians including Don Markstein "America's first ongoing comic book series to fall squarely within the horror genre",[5][6] the feature, set in New York City circa 1930, starred a guttural, rampaging creature actually dubbed "Frankenstein" (unlike Shelley's nameless original monster).

Young Romance

Launched with a cover date of September 1947, the Prize Group title Young Romance signaled its distinction from traditional superhero and genre comics with a cover banner stating the series was "designed for the more adult readers of comics". Told from a first person perspective, underlining its claim to be recounting "true" stories, the title was an instant success, "bec[oming] Jack and Joe's biggest hit in years" and selling "millions of copies"[7] and a staggering 92% of its print run.[8] Crestwood increased the print run by the third issue to triple the initial numbers, as well as upgraded the title from bimonthly to monthly through issues #13–72 (Sept. 1949 – Aug. 1954).[7][8][9]

Within a year and a half, Simon & Kirby were launching companion titles for Crestwood to capitalize on the success of this new genre. The first issue of Young Love (Feb. 1949) also sold well with "indistinguishable"[8] content from its parent-title.[3] Further spin-off titles Young Brides (married couples' stories) and In Love ("book-length" stories) also followed from Crestwood/Prize, and were produced by the Simon & Kirby stable of artists and writers.[8]

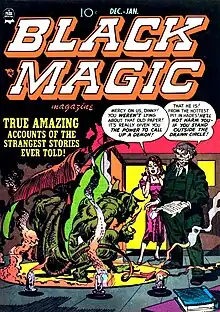

Black Magic

The long-running horror/suspense title Black Magic debuted in 1950. According to Jack Kirby, the idea for Spider-Man originated with him and Simon, who developed a character called The Silver Spider for Black Magic, who was subsequently not used.[10] Ironically, eventual Spider-Man co-creator Steve Ditko drew a six-page story in Black Magic vol. 4, #3 (Dec. 1953).

Controversy

In 1954, a Crestwood/Prize salesman urged Kirby and Simon to launch their own comics company, Mainline Publications,[3][11] while the duo continued to produce work for Crestwood under contract.[11] When the duo rearranged and republished artwork from an old Crestwood story in the Mainline title In Love, Crestwood refused to pay Simon and Kirby.[12] After reviewing Crestwood's finances, Simon & Kirby's attorney stated that the company owed them $130,000 over the past seven years. Crestwood paid them $10,000 in addition to their recent delayed payments.[13]

Decline

Crestwood gave up publishing comics in 1963, selling off its remaining romance comics to publisher DC Comics.[14] It continued to publish humor magazines, such as Sick, up until 1968 (when Sick was acquired by Hewfred Publications).

Comic-book characters

- Airmale

- American Eagle

- Atomic Man

- Black Owl

- Blue Streak

- Bulldog Denny

- Captain Gallant

- Dr. Dekkar, Master of Monsters

- Dr. Frost

- The Futureman & Jupiter

- Green Lama (also published in pulp magazines and by Spark Publications)

- Junior Rangers

- Master Magician

- Power Nelson

- Ted O'Neil

- Yank & Doodle

Titles published

| Title | Series | Issues | Dates | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All for Love | #1 – vol. 3, #4 [#17][15] | 1957–1960 | Went on hiatus, relaunched as Young Love. | |

| Black Magic | #1 – 50 | 1950–1961 | Renamed Cool Cat. | |

| Cool Cat | #51 – 53 | 1962 | ||

| Charlie Chan | #1 – 5 | 1948–1949 | ||

| Fighting American | #1 – 7 | 1954–1955 | ||

| Frankenstein Comics | #1 – 33 | 1945–1954 | ||

| Headline Comics | #1 – 77 | 1943–1956 | ||

| Justice Traps the Guilty | #1 – 92 | 1947–1958 | ||

| Prize Comics | #1 – 68 | 1940–1948 | ||

| Prize Comics Western | #69 – 119 | 1948–1956 | Continues from Prize Comics. | |

| Strange World Of Your Dreams | #1 – 4 | 1952–1953 | ||

| Treasure Comics | #1 – 12 | 1945–1947 | ||

| Western Love | #1 – 5 | 1949–1950 | ||

| Young Brides | #1 – 30 | 1952–1956 | ||

| Young Love | Series 1 | #1 – 73 | 1949–1957 | |

| Series 2 | #18 – 126 | 1960–1963 | Continued from All For Love, continued at DC Comics. | |

| Young Romance | #1 – 208 | 1947–1963 | Continued at DC Comics. |

References

Notes

- Prize Group at the Grand Comics Database

- Simon, Joe, with Jim Simon. The Comic Book Makers (Crestwood/II, 1990) ISBN 1-887591-35-4; reissued (Vanguard Productions, 2003) ISBN 1-887591-35-4, pp. 123–125.

- Ro, Ronin (2004). Tales to Astonish: Jack Kirby, Stan Lee and the American Comic Book Revolution. Bloomsbury USA. p. –. ISBN 1-58234-345-4.

- Grand Comics Database: Prize Comics #7 (Dec. 1940)

- Frankenstein (1940) at Don Markstein's Toonopedia

- Watt-Evans, Lawrence. "The Other Guys", The Scream Factory #19 (Summer 1997), reprinted as "The Other Guys: A Gargoyle's-Eye View of the Non-EC Horro Comics of the 1950s" at Alter Ego #97, October 2010, pp. 3–33. On page 5 of the latter, the author notes, "...there were no horror comics as such in the earliest days. The first real horror series seems to have been the 'Frankenstein' series by Dick Briefer, in Prize Comics ... [which was] "The Other Guys: Pre-Code Horror Comics". Archived from the original on 2009-04-22. Retrieved 2011-07-12. a superhero title, featuring the Black Owl, the Green Lama, and the like, except for this one aberration".

- Ro, p. 46

- Howell, Richard, "Introduction" to Real Love – The Best of the Simon and Kirby Romance Comics" 1940s–1950s (Eclipse Books, 1988).

- Miller, J. J., Thompson, Maggie, Bickford, Peter & Frankenhoff, Brent, The Comic Buyer's Guide Standard Catalog of Comic Books, 4th Edition (KP Books, 2005) – "Young Romance", pp. 1599–1601

- Jack Kirby in "Shop Talk: Jack Kirby", Will Eisner's Spirit Magazine #39 (February 1982): "Spider-Man was discussed between Joe Simon and myself. It was the last thing Joe and I had discussed. We had a strip called 'The Silver Spider.' The Silver Spider was going into a magazine called Black Magic. Black Magic folded with Crestwood ... and we were left with the script. I believe I said this could become a thing called Spider-Man, see, a superhero character. I had a lot of faith in the superhero character that they could be brought back ... and I said Spider-Man would be a fine character to start with. But Joe had already moved on. So the idea was already there when I talked to Stan".

- Beerbohm, Robert Lee (August 1999). "The Mainline Story". Jack Kirby Collector. No. 25. Archived from the original on May 26, 2011. Retrieved March 26, 2008.

- Ro, p. 55.

- Ro, p. 56.

- Don Markstein's Toonopedia: "Romance Comics". Accessed May 27, 2008.

- All for Love at the Grand Comics Database

Sources

- Prize at the Grand Comics Database

- Prize Publications at the Comic Book DB (archived from the original)