Fengli

Fengli (simplified Chinese: 风狸; traditional Chinese: 風狸/風貍; pinyin: fēng lí,[lower-alpha 1] literally 'wind leopard cat') is a legendary or mythified flying mammal of China, whose descriptions from various sources were collated in the Taiping Yulan encyclopedia (10th century ) and the Bencao gangmu (16th century) compendium of materia medica.

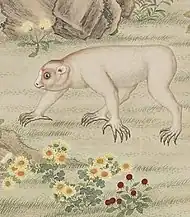

(34)Bk51-fol03rD-furi.jpg.webp)

Guangxi (廣西) was among the places where it could be found (cf. §Geographical range)

It is called fūri by Japanese sources dating back to the Edo period.

Overview

The beast is described as resembling a dark-colored or blue-green (or greenish yellow and black) animal spotted like a leopard but smaller, about the size of a wildcat (leopard cat) or marten. Alternate sources say the beast resembles a vanishingly short-tailed monkey, or a rabbit. It is capable of flying or gliding across trees or jutted rocks, eating fruits. Sources say that its alias fengshengshou favors eating spiders.

The fengli bears a number of other aliases, including fengmu (风母; 風母; fēng mǔ; Japanese: fūbo,[3] literally "wind mother"), fengshengshou (风生兽; 風生獸; fēng shēng shòu,[lower-alpha 2]), pinghou (平猴; píng hóu,[lower-alpha 3] 'flat monkey'), etc.

A collated account of the fengli is given in the Bencao gangmu (1596), under its "Four Legged Animals II" section, but it misstates some alias names and work titles, drawing from such sources as the entry for "fengmu" in the encyclopedia Taiping yulan (c. 980).

The beast lore could have been based on actual fauna; the fengli may in fact have been the colugo according to one hypothesis, or a palm civet or a slow loris according to others.

The fengli has a number of lore attached to it. It is said to carry a magical wand (or a broken stalk of grass), which when pointed at a prey can cause it to fall off a tree (cf. §hunting wand). It is also said to die easily by striking, but such death is feigned, and it will revive momentarily upon receiving wind upon it. It is supposedly immune to cutting by blade, or burning by fire. But plugging its nose with the sweet flag (root portion) was considered lethal to it. Otherwise, only by rupturing its brain and breaking its bones could it be killed completely.

Its urine purportedly was effective against leprosy, according to the old Chinese pharmacopoeia.

The jiqu (狤𤟎; jí qū), which reputedly ate perfume (Indian frankincense, or mastic) was described as a separate beast in the original source, but has been equated with the fengli by the Bencao gangmu.

Nomenclature

The beast fengli (风狸; 風狸[4]/風貍[5]), literally 'wind leopard cat',[6] is described under that title in the Bencao Gangmu (1782)[1596]. The fengli article was originally a sub-article within the preceding leopard cat article.[7][8][lower-alpha 4]

The creature's name is pronounced fūri in Japanese, but (erroneously) glossed as kazetanuki (風貍/かぜたぬき) or 'wind racoon dog' in the Wakan sansai zue,[11][12] due to the fact that li (simplified character: 狸) is commonly read as tanuki by the Japanese.[14]

Aliases and sources

A number of aliases for fengli are given in the Bencao Gangmu, one of them being fengmu (风母; 風母; fēng mǔ or 猦𤝕[16], literally “mother of wind”[17]),[5][18][6] which is the heading used in the Taiping yulan encyclopedia.[19][lower-alpha 5]

The fengli name has its original source in the [Guihai] Yuheng zhi ([桂海]虞衡志; "Treatises of the Supervisor and Guardian [of the Cinammon Sea]")[lower-alpha 6][21] and referred to as wind cat in an English translation from this source.[22]

The fengmu alias can be sourced to the Nanzhou yiwu zhi (南州异物志; ~異物志, "Records of Extraordinary Things from Nanzhou", miscited as the Guangzhou yiwu zhi 广州~; 廣州~),[20][23] and these "Records" also provide the alias pinghou (平猴; píng hóu;[18][6] Japanese:heikō;[12] “flat monkey”[?][17]).[24]

Also fengshengshou (風生獸; fēng shēng shòu,[lower-alpha 7] 'wind-life/birthing-beast'[?][25]) is given in the [Hainei] Shizhou ji ([海内]十洲記, "Records of the Ten Islands [Within the Sea]"[26]) [27] and the Baopuzi.[28]

And fengxing (風猩; fēng xīng is the name quoted from the Lingnan yiwu zhi (嶺南異物志, "Records of Extraordinary Things from Lingnan") in the encyclopedia.[19][lower-alpha 8]

While the beast jiqu (狤𤟎, Japanese: kikkutsu[30]) is treated as another alias of fengli by the Bencao gangmu, the jiqu is treated in a separate chapter (Ch. 16) in the original source,[31] and presumably distinct from fengli as far as the source (Youyang zazu) is concerned, placing these in Books/Chapters 16 and 15, respectively.[32] The reputation of eating a type of perfume[33] (mastic[6]) is attributed to the jiqu.[31] Its characteristics are rather different and shall be segregated and discussed under §Jiqu below.

Geographical range

The fengli dwelled in such places as Yong zhou (in present-day Guangxi), one of the old provinces (zhou) in the Lingnan[37](areas south of the "Five Ridges"/Wuling Mountains), and elsewhere further south in Lingan.[lower-alpha 9][6][18]

The fengli was also found in certain western parts of Shu (蜀, archaic for Sichuan), in areas called the "outside of Xijao" (蜀西徼外).[38][lower-alpha 10][lower-alpha 11]

Non-native to Japan

The fengli (fūri) was not a creature known to be found in Japan so far as Terajima Ryōan knew, according to his Wakan sansai zue.[40] However Negishi Yasumori, the author of Mimibukuro, thought it was just a "type of tanuki (racoon dog)", and felt that human encounters with it in Japan were documented.[41]

External appearance

Size

The fengli is said to measure about the size of a li (leopard cat)[44] or an otter according to the Bencao gangmu.[45][6][18]

The fengshengshou (風生獸) is rather described as blue/green leopard-like, but about the size of a xingxing[28][27] which is tentatively identified as orangutan,[46][47] suggesting perhaps a large beast. However, scribal errors seems to be in play, because while xingxing (orangutan-sized) is traceable to Baopuzi as quoted in encyclopedia,[28] the original text reads li (狸, "badger-sized") in the Baopuzi itself.[15][43]

And there is the alias fengxing (風猩), presumably meaning 'wind orangutan', but the beast there is described as being monkey- or ape-like yet small.[48][49]

Coat and color

The creature, described by its different aliases, is likened to several different animals depending on the source.

The amalgamated profile of the fengli according to the Bencao gangmu is that its fur has markings similar to a leopard, and is multicolored, either "blue-green, yellow, and black",[18] or "greenish-yellow and black",[6] depending on the translator.[lower-alpha 12] The BCGM also says it is a short-tailed (almost tailess) beast resembling a small ape or monkey, with red eyes.[6][18]

Breakdown by source

The creature fengshengshou (風生獸) is described as blue (or rather green)[50] and leopard-like in two sources quoted by the encyclopedia.[27][28]

However, one of the two sources quoted secondhand, the Baopuzi, provides quite a different reading when the standalone edited text is consulte. The BPZ actually describes the fengshengshou as a beast that "resembles a diao(貂) [marten or sable].. [which] is dark[lower-alpha 13] in color and as big as a li (狸) or badger".[28][43]

As for the simian resemblances, the fengli is said to resemble a hwangyuan (黃猨) or "yellow gibbon" according to the aforementioned [Guihai] Yuheng zhi ("Treatises.. [of the Cinammon Sea]"),[lower-alpha 14][21][22] while fengli resembled a ju- monkey (狙)), had long eyebrows and tended to shy away, according to the Youyang zazu (酉陽雜俎"; "a Miscellany from Youyang").[32][17] The fengmu beast (風母獸) which bore the alias pinghou (平猴) or “flat monkey” was monkey-like, hairless, and red-eyed according to the Nanzhou yiwu zhi.[lower-alpha 15][51] The fengli resembles a rabbit according to one source.[52]

Behavioral traits

The fengli resembles a rabbit and is small according to Chen Cangqi, and it captures the wind, travels tree to tree, eating fruits.[52][18][6]

But the preferred food is also said to be the spider for the fengmu beast[48] or the fengli.[21][22][53][lower-alpha 16]

It is said to curl up like a hedgehog (蝟) by day,[48][21] and by night it turns active and agile,[48] or flies in air when the wind rises,[21] or "jump[s] very high with the wind, crossing cliffs and pasing above trees―like birds flying in the air", as the BCGM sums it up.[6][54]

Capture, feigned death, killing method

The BCGM writes that when the creature encounters a human, they present a shy demeanor, "bend their head and seem to beg for mercy",[55][6][lower-alpha 17] though an original source words it somewhat differently.[57]

The fengli (fengxing[lower-alpha 18], fengshengshou[lower-alpha 19]) will seem to die easily when struck, but resuscitates momentarily upon turning its mouth toward the wind.[58][6][59] The fengshengshou is reputedly immune to penetration by blade, and also incombustible when attempted to burn with fire, and can only be completely killed by pulverizing its bones and breaching its brain.[60][6][61]

Another piece of lore is that it can also be killed instantly by plugging its nose with the rhizome[18] (root[63]) of the sweet flag (Acorus sp.[6]) particularly the Acorus gramineus species (石菖蒲, "grassleaf sweet flag").[18][64][65]

Hunting wand

According to the lore of southerners, the fengli always carries a small stick or wand (杖) which when pointed at renders (the birds or beasts[66]) incapable of flying or running[48] (or immobilizes them).[66][6] When a human obtains this wand, mere pointing at the prey will ensure its capture. But even if the fengli is netted, the wand will not be found (it has discarded the tool[66]). But by caning the fengli a hundred times[48] (or by severely hitting it[66]) the animal will be persuaded to point to the whereabouts of the wand.[6]

Other sources report somewhat differently on the wand. The wand owned by is more difficult to obtain than the yixingcao (翳形草, tr. as 'grass that covers up [your] body' (a sort of grass of invisibility)[17]) according to the experts of the art of treating wind diseases. This "wand" is actually a piece of grass stalk that the fengli breaks off, measuring a little over 1 chi or Chinese foot (thus not something it carries always), and in order to catch it in action, humans span a length of rope between trees, then conceal themselves in the hollow of a nearby tree. After about three days' wait, the creature will come, and finding a flock of birds gathered in the trees, points at them with the grass-stalk causing them to fall, and starts eating. Humans emerge to capture it, but the fengli typically swallows the grass or flings it away. Thus it is struck several hundred times until it is willing to retrieve the correct grass.[32][17]

The magic grass of the fūri is also mentioned in the Edo Period essay Mimibukuro, and includes an anecdote that someone who stole the grass a fūri, tried to catch the bird by climbing a tree, and when he held it out the bird, the bird and that person both fell from the tree.[lower-alpha 20][41][42]

Medicinal claims

The blend of this brain[lower-alpha 21] with chrysanthemum flowers extends one's life (by 500 years[43]) after administering 10 jin (catties, Chinese pound) of the medicine.[68][6][43] The longevity claim was made proably due to the reasoning that the long-lived immortals (xianren) were also considered to be capable of flight (like the fengli), according to the commentary by Minakata Kumagusu.[69]

The urine is also said to treat "massive wind" (大風, i.e., leprosy[70]).[71] Certain ailments were believed caused by wind, hence, the wind creature's urine was believed effective.[69]

Its urine is milk-like, and hard to obtain, but can be procured if the beast is raised in a farm.[6]

Jiqu

The jiqu (Chinese: 狤𤟎/吉屈[72]; pinyin: jí qū, Japanese: kikkutsu[30] or kekkutsu[73]) is a beast whose name is tentatively translated as "the one that bows to good fortune"[?].[17]

According to the Youyang zazu (酉陽雑俎) it likes to eat a type of aromatic substance called xunlu xiang (薰陸香; xūn lù xiāng),[31][17] namely "Indian frankincense",[74]

The fengli considered synonymous to jiqu in the BCGM, it is described as feeding on this frankincense/olibanum,[18] or mastic.[75][6][76] It was probably only local rumour that the beast ate this perfumewood resin, according to a scholar in the field perfume ingredients.[72]

A large jiqu weighed 10 catties [≈pounds], and bore resemblance to an otter. It was almost hairless, with no hair on the head, body, or its for limbs, but a blue (green) stripe of fur ran from its nose, along the spine, down to its tail, about 1 cun [≈inch] wide, with individual hairs about 3 or 4 fen (0.3–0.4 cun).[31][17][77]

Identification with actual fauna

Colugo

The fengli in writings was hypothesizes to be a colugo, a bat-like mammal,[lower-alpha 22] by Minakata Kumagusu (1920).[69][42] The colugo's wing is furry on the upper side, unlike the smooth-winged bat.[69]

While the fengli (fūri) is identifiable with the colugo, a flying yōkai called nobusuma may be identifiable with the musasabi or the Japanese giant flying squirrel (Petaurista leucogenys),[42] according to some Japanese opinion. Cf. next section on §Giant flying squirrel

Giant flying squirrel

A tentative identification with the red giant flying squirrel (Petaurista petaurista: Chinese: 棕鼯鼠) has been suggested by Yang Wuquan.[80]

Palm civets

Suzuki's 1931 Japanese translation of the Bencao gangmu (Honzō kōmoku) under this entry indicates its scientific name to be uncertain, but in the marginal notes mentions ichthyologist Shigeru Kimura's opinion it may be the musang or the common Asian palm civet.[lower-alpha 23][81]

A Chinese scholar has also explored the possibility that the masked palm civet (Paguma larvata, Chinese name: 果子狸 guozili) might be attested as fuli in classical Chinese writings.[82]

Slow lorises

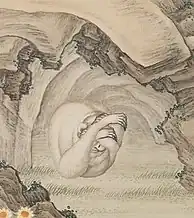

Ignatius Sichelbart (Chinese: 艾啓蒙) who served as court painter for the Qing Emperors painted Fengxing tu[lower-alpha 24] (Fig. right) in realistic precise detail, and is considered to have portrayed a slow loris.[83]

The identification of fuli as slow loris actually occurs in B. E. Read's Materia Medica (RMM for short), although he employed the Chinese name of the beast, lan hou (树懒; 懒猴), which he literally translated as a "sloth monkey".[84][85][86]

The opinion that the fengli belongs to the slow loris genus (懶猴属) Nycticebus is also elocuated in a paper by Tochio (2004), a scholar of natural history.[lower-alpha 25][87]

Explanatory notes

- The combined-character romanization (fengli, as used by Luo tr.), will be used instead of separated romanization (feng li) used by Unschuld tr., but pinyin phoneticization with diacrtics (fēng lí) will be appended.

- Japanese:fūseijū.

- Japanese:heikō.

- Suzuki identifies li as Lynx microtid[9] (recté microtis), but this is still a synonym for the leopard cat or a subspecies thereof. The leopard cat Prionailurus bengalensis was also published under the P. euptilura synonym, and microtis was regarded as the subspecies of the latter.[10]

- Taiping yulan: "Fengmu"quotes sources under alternate names of the beast,[19] though not fengli.

- Cited by LSZ(Li Shizen) in BCGM[18][6] in shorthand as Yuheng zhi ""Treatises of the Supervisor and Guardian".[20]

- Japanese:fūseijū.

- Which is correct over fengmu being quoted from the same source in BCGM,[5] and it is emended thus in the edition of BCGM edited by Ju Chenglong 胡承龍 (2016).[29]

- Lingnan extended from Guangxi to Guangdong and Hong Kong, etc.

- "Shu xi jiao wai" (蜀西徼外) is glossed as a regional name in Sichuan, encompassing Kangding district and Aba district of Sichuan.[39]

- "Shu xi" (蜀西) alone refers to western Sichuan, and Suzuki tr. (1931), p. 352 parsed it differently as "outside the borders (徼外 jiao wai, Japanese:kōgai) of Shuxi (Western Sichuan).

- The BCGM notes that the creature has a blue stripe of hair runnig from nose to tail, but this is actually a description of another beast (cf. §Jiqu) which is conflated in the BCGM.

- Here qing (靑) which means "blue/green" is rendered as "dark".

- [桂海]虞衡志

- 《南州異物志》.

- BCGM mentions eating perfume (mastic) for food, but this is attributed to the jiqu, which the original source treats as a separate creature (Cf. §Jiqu).

- The term 叩頭 is construable as kowtow. Just to illustrate, in an entirely different work, this term is rendered as "knock his head on the ground".[56]

- 風猩

- 風生獣

- The Chinese source used by the Mimibukuro is unclear; although the author says he learned it from Soushen Ji (捜神記) there is no mention of fengli anywhere in that work (notes in Hasegawa ed.)[67]

- "This brain": Luo translates as "this medicine", suggesting it to be not just brain, but the concoct mentioned beforehand, namely, the brain steeped in wine said to treat "wind ailments", according to the Lingnan yiwuzhi.[18]

- Some biologists then considered colugo to be closely related to the bat, while others had different opinions, as Minakata explains. Even mythographer Miyoko Nakano stated the colugo was close to a bat in a 2002 book.[78]

- Paradoxurus hermaphroditus. Kimura gave P. musanga but this is an outdated synonym. The Japanese common name is given here as kinobori zaru (キノボリザル) literally "tree-climbing ape".

- simplified Chinese: 《风猩图》; traditional Chinese: 《風猩圖》.

- However, Tochio's main topic is another mammal entirely, and in his digression here, he erroneously swapped the Chinese names "蜂猴" (loris) and "懶猴" (slow loris). Him calling Lorisidae "懒猴科" is not wrong, however, Nycticebus must be "懒猴属" and Nycticebus coucang (Sunda slow loris) actually "懒猴", which he swaps.

References

- Citations

- Toriyama, Sekien [in Japanese] (1805). "Fūri" 風狸(ふうり). Hyakki yakō shūi (Konjaku hyakki shūi) 3 kan 百鬼夜行拾遺(今昔百鬼拾遺) 3巻. Vol. 2. Nagano Kankichi.

風によりて巌をかけり木にのぼり、そのはやき事飛鳥の如し

- Shida, Shida [in Japanese]; Saeki, Tsunemaro, eds. (1909). "Fūbo" ふうぼ【風母. Nihon ruigo daijiten 日本類語大辞典. Seikōkan. p. 1323.

支那に住し猿に似たる獣

- The reading is not given in Suzuki tr. (1931) but it has been verified in a dictionary.[2]

- Li Shizhen (1596). . Bencao Gangmu 本草綱目 (in Chinese) – via Wikisource.

- Li Shizhen (1782) [1596]. . Bencao Gangmu (Siku Quanshu) 本草綱目 (四庫全書本) (in Chinese) – via Wikisource.

- Li Shizhen (2021). "Four-legged Animals II. 51-24 Feng li wind leopard cat" 風貍. Ben Cao Gang Mu, Volume IX: Fowls, Domestic and Wild Animals, Human Substances. Translated by Unschuld, Paul U. Univ of California Press. pp. 920–922. ISBN 9780520379923.

- Suzuki tr. (1931), p. 352: "もとは貍の條下に附記してあったが.. Though it was originally appended under the li article."

- Suzuki tr. (1931). "貍" pp. 346ff; Unschuld tr. (2021) Chapter/section 51-24. Leopard cat, pp. 807ff.

- Suzuki tr. (1931), p. 346.

- North Manchuria Economic Research Office, South Manchuria Railway/Mantetsu Hokuman Keizai Chōsajo (1939). "Prionaelurus euptilura microtis (A. Milne-Edwards), 1871" ヤマネコ. Hokuman yasei honyūruishi 北満野生哺乳類誌. 興亜書院.

- Terajima, Ryōan [in Japanese] (1712), "38. Beasts: Fūri" 三十八 獣類:風貍, Wakan sansai zue: 105 kan shu 1 kan bi 1 kan 和漢三才図会 : 105巻首1巻尾1巻, vol. 26 of 81, Kan-no-38, fol. 21r

- Terajima, Ryōan [in Japanese] (1987). Wakan sansai zue 和漢三才図会. Vol. 6. Translated by Shimada, Isao [in Japanese]; Takeshima, Atsuo; Higuchi, Motomi. Heibonsha. p. 93. ISBN 978-4-582-80466-9.

- Terajima Ryōan (1712) Wakan sansai zue, "Kan-no-38. Beasts:貍 Tanuki"

- Thus li (貍) in the preceding section of 'BCGM was misconstrued as "tanuki" or racoon dog (also in its preceding section) in the WSZ (Wakan sansai zue).[13]

- Guo li bian yi guan 國立編譯館 / Zhonghua cong shu bian shen wei yuan hui [in Chinese]; Zhonghua wen hua fu xing yun dong zong hui 中華文化復興運動總會, eds. (2001). "仙藥篇第11". Baopuzi neipian jin zhu jin yi 抱朴子內篇今註今譯 (in Chinese). Notes and translation by Chen Feilong. Taiwan Commercial Press. p. 433. ISBN 9789570516807.

- Styled thus with the additional beast radical "犭" (犭+風; 犭+母) in the Yupian 玉篇 "Jade Chapters" under the part for the dog [radical] 犬部. Yupian explains fengmu to be a tailed beast which even after being struck dead shall revive after receiving wind.[15]

- Duan Chengshi (2021). "The jiqu 狤𤟎: "the one that bows to good fortune"?". On Feathers and Furs: The Animal Section in Duan Chengshi's 段成式 Youyang zazu 酉陽雜俎 (ca. 853). An annotated translation. Translated by Chiara Bocci. Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 145–152. ISBN 9780520379923. JSTOR j.ctv2bfhhkv.

- Li Shizhen (2003). "Drug 51-24 Fengli". Compendium of Materia Medica: Bencao Gangmu. Vol. 6. Translated by Luo Xiwen [in Chinese]. Foreign Languages Press. pp. 4079–4080. ISBN 9787119032603.

- . Taiping yulan 太平御覽 (in Chinese). c. 980 – via Wikisource.

- Zheng, Jinsheng; Kirk, Nalini; Buell, Paul D.; Unschuld, Paul Ulrich, eds. (2018). "Guang zhou yi wu zhi /Gui hai Yu heng zhi". Dictionary of the Ben Cao Gang Mu, Volume 3: Persons and Literary Sources. University of California Press. pp. 158, 159. ISBN 9780520291973.

- Fan Chengda [in Chinese], Guihai yuhengzhi 桂海虞衡志 (in Chinese), ¶75.

- Fan Chengdai (2021). "Quadrupeds. § Wind cats [Fengli]". Treatises of the Supervisor and Guardian of the Cinnamon Sea: The Natural World and Material Culture of Twelfth-Century China. Translated by James M. Hargett. University of Washington Press. pp. 78–79. ISBN 9780295802060.

- The Taiping yulan cites Nanzhou yiwu ji (~记; ~記[19] but emendable to ~yiwu zhi[20] the trivial alteration of the final character meaning "history/records" being commonplace. Zheng et al.'s notes on BCGM, on the source "Guangzhou yiwu zhi notes this is quoted secondhand from the Taiping yulan and the latter gives Nanzhou (ditto).[20]

- Nanzhou yiwu ji quoted in Taiping yulan.[19]

- The exact intended meaning is ambiguous. Translators of BCGM (Unshuld, Luo) don't bother to provide the meaning of aliases other than fengli. Bocci renders jiqu and pinghou but not fengshengshou.

- Zheng et al. (2018) "Shi zhou ji", pp. 920–922

- [Hainei] Shizhou ji 《[海内]十洲記》 on "fengshengshou 風生獸", apud Taiping Yulan

- Baopuzi Baopuzi neipian 抱朴子·內篇 on "fengshengshou 風生獸", apud Taiping Yulan

- Li Shizhen (2016). "Feng li <shiyi>" 風狸《拾遺》. In Hu Chenglong 胡承龍 (ed.). The Ben Cao Gang Mu: Chinese Edition (in Chinese). Univ of California Press. pp. 1469–1470. ISBN 978-0-520-95974-3.

- Suzuki tr. (1931), p. 352.

- Duan Chengshi (1781) [c. 860]. . Youyang zazu (Siku quanshu) 酉陽雜爼 (四庫全書本) (in Chinese) – via Wikisource.

- Duan Chengshi (1781) [c. 860]. . Youyang zazu (Siku quanshu) 酉陽雜爼 (四庫全書本) (in Chinese) – via Wikisource.

- xunluxiang (薫陸香), Japanese: kunroku kō (薫陸香)[30]

- Luo tr. (2003), p. 3839

- Unschuld (2021), Volume IX: Fowls, etc.:

- Luo tr. (2003),Volume IX: Fowls, Fowls: 49-17-A01 Qinjialo 秦吉了, p. 3839

- Yong zhou is given as one of four provinces or zhou (of minority peoples[34]) within Lingnan where the bird qinjialo 秦吉了 (aka jieliao niao 結遼鳥) can be found (BCGM, "Fowls").[35][36]

- "outside of Xi jiao in Shu",[6]; "outside Xijiao in Sichuan"[18]。

- Zheng et al. (2018), 蜀西 Shu xi, 蜀西徼外 Shu xi jiao wai . p. 281

- "未聞在于本朝"[11]。"風狸は嶺南(広東・広西地方)の山林中に多くいて、まだわが国にいるとは聞かない".[12]

- Negishi Yasumori [in Japanese] (1991). "Fūri no koto" 風狸の事. In Hasegawa, Tsuyoshi [in Japanese] (ed.). Mimibukuro 耳嚢. Iwanami bunko. Vol. 2. Iwanami. p. 220. ISBN 978-4-00-302613-7.; ――(1972), Heibonsha, p. 133

- Miyamoto, Yukie (2013). "Dai-4-shō. Sora to umi no yōkai. §Fūri" 第4章 空と海の妖怪 §風狸. Nihon no yōkai FILE 日本の妖怪FILE. Gakken. pp. 116–117. ISBN 978-4-054056-63-3.

- Feifel, Feifel [in German], ed. (1946). "Pao-P'u Tzu 抱朴子 Nei-P'ien 內篇 Chapter XI". Monumenta Serica 華裔學志. 11: 13–14. doi:10.1080/02549948.1946.11744875. JSTOR 40725995.

- Again, often misconstrued as tanuki, i.e., racoon dog by Wakan sansai zue,[11][12] and even recent Japanese sources.[42] In some editions of the BCGM, the use of the simplified character of li (狸 can be found, easily read as "tanuki" by the Japanese. And the simplified li (狸) is also used in the relevant passage in Baopuzi,[15] and the description transated as "as big as a badger" by Feifel.[43]

- "其大如狸如獺"[4][5]。

- Unschuld tr., BCGM IX: "Fowls, Domestic and Wild Animals,..". Four-legged Animals III. 51-52. Sheng sheng 猩猩. pp. 920–922

- Luo tr. (2003), pp. 4128–.

- Lingnan yiwu zhi 嶺南異物志 on "fengxing 風猩", apud Taiping Yulan

- Cf. BCGM, "physical appearance is that of monkeys, but they are smaller".[6]

- The term qing (靑) ambiguously means "blue, green, or blue-green", as a matter of common knowledge. Note that in the description from BCGM given above, Luo renders as "blue-green" and Unschuld as "greenish".

- Nanzhou yiwu zhi 《南州異物志 》(apud 『Taiping Yulan, which calls it ~ji 記. It is referred to as Ganzhou yiwu zhi 《廣州異物志》 in the Bencao Gangmu, as aforestated.

- Chen Cangq. Bencao shiyi?, quoted by BCGM: "藏器曰風貍生邕州以南似兎而短棲息高樹上候風而吹至他樹食果子其尿如乳甚難得人取養之乃可得"[4][5]。

- Also used in the BCGM: "其性食蜘蛛".[4][5]

- "晝則踡伏 不動如蝟 夜則因風騰躍甚捷 越巖過樹 如鳥飛空中[5]。または「蜷伏」とつくる[4]。

- "人網得之 見人則如羞而叩頭乞憐之態".[4][5]

- Pettit, J. E. E.; Chao-jan, Chang (2020). A Library of Clouds: The Scripture of the Immaculate Numen and the Rewriting of Daoist Texts. University of Hawaii Press. p. 259. ISBN 9780824884376.

- "若行逢人,便叩頭,狀如懼罪自乞" in the Nanzhou yiwuji [sic.] quoted in the Taiping yulan encyclopedia.[51] A published English translation wanting, but the latter phrase is literally "as if to beg for guilt (or fear of punishment)" which does not quite make sense.

- BCGM: "人撾擊之 倏然死矣 以口向風.[4][5]

- Cf. fengshengshou in Shizhouji[27] and Lingnan yiwuzhi.[48]

- "須臾複活 惟碎其骨 破其腦乃死 一云刀斫不入 火焚不焦 打之如皮囊 雖鐵擊其頭破 得風複起"[4][5]

- Cf. fengshengshou in Shizhouji[27] and BPZ.[15]

- Fang Yizhi [in Chinese] (1884). "風生獸". 物理小識: 十二卷. 寧靜堂. p. 巻十 十二裏.

- Though not explicit in the Chinese text, "root" is parenthetically inserted in the Unschuld tr.[6] The word for "root" is also interpolated in the quote in the 17th commentary by Fang Yizhi: "十洲云以石菖蒲根塞鼻乃死"[62]

- "惟石菖蒲塞其鼻 即死也".[4][5]

- A variant reading states that a sweet flag (Acorus calamus) growing on top of stone should be used (fengshengshou 「風生獣」 in BPZ 《抱朴子・内篇》[15][43]、'fengshengshou 「風生獣」 in Shizhouji 《[海内]十洲記》[27]).

- Liangnan yiwuzhi 嶺南異物志 apud BCGM.

- Yabuno, Tadashi (2015-03-17). "Mimibukoro kan-no-jū Fūri no koto" 耳嚢 巻之十 風狸の事. 鬼火 Le feu follet. Retrieved 2023-01-24.

- Shizhouji,[27] quoted as "腦主治酒浸服愈風疾〈時珍 出嶺南志〉和菊花服至十觔可長生〈十洲記〉".[4][5]

- Minakata (1920) Jūnishi-kō: Saru 十二支考・猴.Minakata (1971), p. 354

- Unschuld tr. (2021), p. 355: Da feng 大風 "massive wind"... sores caused by a massive intrusion of wind evil and also to conditions of leprosy.

- Guihai yuhengzhi 《桂海虞衡志》,[21][22]、Yuhengzhi apud BCGM.[6][18]

- Yamada, Kentaro [in Japanese] (1974). "Nyūkō・motsuyaku shōshi" 乳香・没薬小史「諸蕃志」の記述を中心にして [A Short History of Frankincense and Myrrh in China]. Journal of Nagoya Gakuin University. Humanities and natural sciences. 2 (3): 76–77.

- Naomi, Genshū (1759), "Kikkutsu" 狤𤟎 キツクツ, Kōyamatohonzō 10kan betsuroku 2 kan 広倭本草 10巻別録2巻, vol. Betsuroku–ge, Nagata Chōbei, pp. 22–23

- Borgen, Robert (2020), "Chapter 5. A Japanese Pilgrim's visit to Wutai in the winter of 1072", in Andrews, Susan; Chen, Jinhua; Kuan, Guang (eds.), The Transnational Cult of Mount Wutai: Historical and Comparative Perspectives, BRILL, p. 152, ISBN 9789004419872

- Mastic is known by the Chinese name yang rushang (洋乳香, characterizing it as a sort of frankincense (rushang).

- BCGM: "亦啖薰陸香".[4][5]

- The BCGM appropriates this description and ascribes it to his fengli: "或云一身無毛 惟自鼻至尾一道有青毛 廣寸許 長三四分 其尿如乳汁".[4][5] Cf. Unschld tr.: "no fur, except for a path.. nose to tail.. covered with greenish fur..," etc.[6] Its urine being milk-like, appended at the end, is not found in the Youyang zazu.

- Nakano, Miyoko [in Japanese] (2002). Songokū no tanjō: saru no minwagaku to Saiyūki 孫悟空の誕生: サルの民話学と「西遊記」. Iwanami. p. 265. ISBN 9784006020507.

- Zhou Qufei [in Chinese] (1999). Yang Wuquan (ed.). Lingwai daida jiaozhu 嶺外代答校注. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju. pp. 9.360–361, n1.

- Yang Wuquan 楊武泉[79] apud Hargett tr. (2011), pp. 77–78, n52.

- Suzuki tr. (1931), p. 351.

- Ceng Xiongsheng (2004). "Zhōngguó lìshǐ shàng de guǒzi lí" 中國歷史上的果子狸. 九州學林. 2 (3): 230.

- "Yī fú "fēng xīng tú", huà zhōng de dòngwù yísì chuānyuè [gǔdài]le, shì qiánlóng yùyòng huàshī de zuòpǐn" 一幅《风猩图》,画中的动物疑似穿越[古代]了,是乾隆御用画师的作品, Tencent 腾讯网 (in Chinese), 2020-03-09

- Read also identifies it as a Loris sp., but that taxonomy is obsolete and slow loris is now filed under the Nycticebus genus.

- Feifel tr., note 70).[43]

- Read, Bernard Emms (1931). Chinese Materia Medica. Peking Natural History Bulletin. p. 3 (#373).

- Tochio, Takeshi (March 2004), "Tenkinshikō wo motomete: Unnan no tabi" 滇金絲猴を求めて : 雲南の旅 [In search of the black snub-nosed monkey: Journey to Yunnan], Seijō kokubungaku (20): 108 repository

- Bibliography

- Minakata, Kumagusu (1920), "Jūnishi-kō(7): Saru ni kansuru minzoku to densetsu" 十二支考(7):猴に関する民俗と伝説, Taiyō 太陽, 26 (1, 2, 5, , 13, 14). Aozora bunko No.2539

- Minakata, Kumagusu (1971), "Saru (sarudoshi)" 猴(申年), Minakata Kumagusu zenshū: Jūnishi-kō 1 南方熊楠全集: 十二支考1, Heibonsha, p. 354, ISBN 9784582429015

- Li Shizhen (1931). "Kemono-bu dai-51-kan jō fūri<shūi>" 獣部第五十一卷 上 風貍〈拾遺〉. Tōchū kokuyaku honzō kōmoku 頭註国訳本草綱目. Vol. 12. Translated by Suzuki, Shinkai. Shunyōdō. pp. 351–451.