Sosarme

Sosarme, re di Media ("Sosarmes, King of Media", HWV 30) is an opera by George Frideric Handel written in 1732 for the King's Theatre in the Haymarket, London, where it ran for 12 performances. The text was based on an earlier libretto by Antonio Salvi, Dionisio, Re di Portogallo (Dionisius, King of Portugal), and adapted by an unknown writer. The original setting of Portugal was changed to Sardis in Lydia.

Performance history

Sosarme had its premiere on 15 February 1732 and was a great success, as noted by the diary known as "Colman's Opera Register": "In Febry Sosarmes - a New Opera - took much by Hendell - & was for many Nights much crowded to some peoples admiration."[1] It was revived for 3 performances in 1734 with arias from Riccardo Primo. The first revival since 1734 was in 1970 at Abingdon, UK, though the work had been broadcast in full by the BBC in 1955, a performance on which the slightly abridged recording of the same year, under Anthony Lewis (listed below) was based.[2] As with all Baroque opera seria, Sosarme went unperformed for many years, but with the revival of interest in Baroque music and historically informed musical performance since the 1960s, Sosarme, like all Handel operas, receives performances at festivals and opera houses today.[3] Among other performances, the opera was staged by the Barber Institute of the University of Birmingham in 1979,[4] by the London Handel Festival in 2004,[5] and at Oper Halle in 2016.[6]

Roles

| Role[7] | Voice type | Premiere Cast, 15 February 1732 |

|---|---|---|

| Sosarme, King of Media | alto castrato | Francesco Bernardi,called "Senesino" |

| Erenice, wife of Haliate | contralto | Anna Bagnolesi |

| Argone, illegitimate son of Haliate | alto castrato | Antonio Gualandi ("Campioli") |

| Melo, son and heir of Haliate | contralto | Francesca Bertolli |

| Altomaro, counsellor to Sosarme | bass | Antonio Montagnana |

| Elmira, daughter of Haliate and beloved of Sosarme | soprano | Anna Maria Strada del Pò |

| Haliate, King of Lydia | tenor | Giovanni Battista Pinacci |

Synopsis

- Scene: Sardis, in antiquity

Melo, son and heir of King Haliate of Lydia, has rebelled against his father and raised an army to try to overthrow him, believing the king wishes to disinherit him in favour of his illegitimate son Argone. Sosarme King of the neighbouring empire of the Medes had been engaged to marry Princess Elmira, Melo's sister, and is invading with an army of his own to try to stop this dynastic war.

Act 1

King Haliate is besieging Sardis, where his rebellious son Melo, his daughter Elmira and wife Erenice are living in the palace. The citizens are starving and Melo decides to launch an attack on Haliate's forces. His mother and sister beg him not to risk injury or death to his father, but Melo will not be moved.

Argone, illegitimate son of Haliate, is also the grandson of Sosarme's counsellor Altomaro, who urges Argone to fight to be proclaimed Haliate's heir, but Argone thinks this would be ignoble.

Sosarme tries to act as a mediator between Melo and Haliate, but Haliate is determined to punish his rebellious son.

Act 2

After the battle, Melo brings into the palace a garment stained with Sosarme's blood and Elmira swoons away at the sight.

Altomaro decides that if Argone will not fight to become king, he himself will attempt to overthrow Haliate.

Sosarme was only wounded, not killed, in the battle, and is brought into the palace where he and Elmira lovingly greet each other.

Haliate decides to spare the people an extended war, and to settle the quarrel with his son Melo by challenging him to fight in single combat.

Act 3

About to fight the duel, Haliate and Melo are interrupted by Erenice and Argone.

Heliate and Melo learn that Altomaro has betrayed them both: news is brought of Altomaro's suicide. Father and son are reconciled and Sosarme and Elmira will marry.[1]

Context and analysis

The German-born Handel, after spending some of his early career composing operas and other pieces in Italy, settled in London, where in 1711 he had brought Italian opera for the first time with his opera Rinaldo. A tremendous success, Rinaldo created a craze in London for Italian opera seria, a form focused overwhelmingly on solo arias for the star virtuoso singers. In 1719, Handel was appointed music director of an organisation called the Royal Academy of Music (unconnected with the present day London conservatoire), a company under royal charter to produce Italian operas in London. Handel was not only to compose operas for the company but hire the star singers, supervise the orchestra and musicians, and adapt operas from Italy for London performance.[8][9]

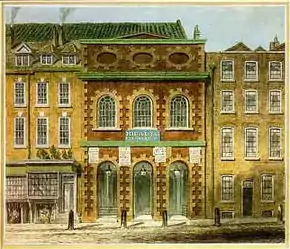

The Royal Academy of Music collapsed at the end of the 1728 - 29 season, partly due to the huge fees paid to the star singers. Handel went into partnership with John James Heidegger, the theatrical impresario who held the lease on the King's Theatre in the Haymarket where the operas were presented and started a new opera company with a new prima donna, Anna Strada.

With two thirds of the score of Sosarme completed, the names of the characters and the setting were changed from historical characters in 14th century Portugal to a mythical Lydia, probably out of fear of offending one of Britain's closest allies, Portuguese King John V.[1]

Dramatist Aaron Hill, who had collaborated with Handel on Rinaldo, wrote in 1732:

We have likewise had two Operas, Etius and Sosarmes, the first most Masterly, the last most pleasing, and in my mind exceeding pretty: There are two Duetto’s which Ravish me, and indeed the whole is vastly Genteel; (I am sorry I am so wicked) but I like one good Opera better than Twenty Oratorio’s.[10]

Viscount Perceval noted in his diary:

“I went to the Opera Sosarmis, made by Hendel, which takes with the town, and that justly, for it is one of the best I ever heard.”[11]

Winton Dean has commented on dramatic weaknesses of the work, including the delayed entrance of Sosarme in the story and his minimal influence on the plot's action, and weak character development. He has also acknowledged the quality of musical inspiration within these limitations. The duet "Per le porte del Tormento", the popularity of which in Handel's lifetime Dean documents, (and which Handel also used in "Imeneo" (1738–40)) was included in nineteenth century Handel anthologies and (in an extract from the 1955 recording) became widely known in Britain in the second half of the twentieth century through the Open University.[2][12]

The opera is scored for two oboes, bassoon, two trumpets, two horns, strings and continuo (cello, lute, harpsichord).

Recordings

- L’Oiseau-Lyre OLS 124-6 (1954): Alfred Deller (Sosarme), William Herbert (Haliate), Margaret Ritchie (Elmira), Nancy Evans (Erenice), Helen Watts (Melo), Ian Wallace (Altomaro), John Kentish (Argone) The Saint Cecilia Orchestra; Anthony Lewis, conductor[12][13]

- Newport NPD 85575 DDD (1994): D'Anna Fortunato (Sosarme), John Aler (Haliate), Julianne Baird (Elmira), Jennifer Lane (Erenice), Drew Minter (Melo), Nathaniel Watson (Altomaro), Raymond Pellerin (Argone). Taghkanic Chorale and the Amor Artis Orchestra, Johannes Somary, conductor.

- Fernando, re di Castiglia, the original version of Sosarme - Virgin Classics 00946548326 (2005): Lawrence Zazzo (Fernando), Filippo Adami (Dionisio), Veronica Cangemi (Elvida), Marianna Pizzolato (Isabella), Max Emanuel Cencic (Sancio), Antonio Abete (Altomaro), Neal Banerjee (Alfonso) Il Complesso Barocco; Alan Curtis, conductor

References

Notes

- "Synopsis of Sosarme". Handelhouse.org. Handel House Museum. Archived from the original on 29 October 2014. Retrieved 10 July 2014.

- Dean, Winton, "Reports: Abingdon" (1970). The Musical Times, 111 (1533): p. 1127, Dean Winton, "Handel's Operas 1726-1741" Boydell 2006 p 228

- "Handel:A Biographical Introduction". Handel Institute. Archived from the original on 2 September 2012. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- FitzGerald, Ann (19 July 1979). "Barber Institute: Sosarme". The Stage. Retrieved 28 March 2019 – via The British Newspaper Archive.

- "Handel's Opera 'Sosarme, Re di Media' at the London Handel Festival 2004". Haendel.cz. Retrieved 10 July 2014.

- "Sosrame". buehnen-halle.de. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- "List of Handel's works". Gfhandel.org. Handel Institute. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

- Dean, W. & J.M. Knapp (1995) Handel's operas 1704-1726, p. 298.

- Strohm, Reinhard (20 June 1985). Essays on Handel and Italian opera by Reinhard Strohm. ISBN 9780521264280. Retrieved 2 February 2013 – via Google Books.

- Aaron Hill : See and Seem Blind Or, A Critical DISSERTATION ON THE Publick DIVERSIONS, &c. Juni 1732. In: William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, University of California, 1986, p. XXIX.

- Editorial Board of the Halle Handel Edition: Handel's Guide: Volume 4 Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig, 1985, ISBN 3 -7618-0717-1, p 197

- Dean, Winton, "Handel's Dramatic Music on Records" (January 1958). Music & Letters, 39 (1): pp. 57-65.

- Hicks, Anthony, "Record Reviews: Sosarme" (July 1972). The Musical Times, 113 (1553): pp. 673-674.

Sources

- Dean, Winton (2006), Handel's Operas, 1726-1741, Boydell Press, ISBN 1-84383-268-2 The second of the two volume definitive reference on the operas of Handel

External links

- Italian libretto

- Sosarme: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project