Loyalists fighting in the American Revolution

Colonists who supported the British cause in the American Revolution were Loyalists, often called Tories, or, occasionally, Royalists or King's Men. George Washington's winning side in the war called themselves "Patriots", and in this article Americans on the revolutionary side are called Patriots. For a detailed analysis of the psychology and social origins of the Loyalists, see Loyalist (American Revolution).

| Loyalists | |

|---|---|

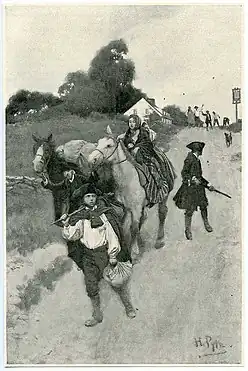

Engraving of the American Revolutionary War, depicting the death of British Major Patrick Ferguson, being shot from his horse on October 7, 1780, as he commanded Loyalist regulars and militia at the Battle of Kings Mountain, a Patriot military victory. | |

| Dates of operation | 1775–1783 |

This article is an overview of some of the prominent Loyalist military units of the Revolution, and of the fighting they did for the British Crown.

The Loyalist population

The number of Americans who adhered to the British side after fighting commenced is still debated. An American historian has estimated that about 450,000 Americans remained loyal to Britain during the Revolution. This would be about sixteen percent of the total population or about 20 percent of Americans of European origin. The Loyalists were as socially diverse as their Patriot opponents but some groups produced more Loyalists. Thus they included many Anglicans (Episcopalians) in the North East, many tenant farmers in New York and people of Dutch origin in New York and New Jersey, many of the German population of Pennsylvania, some Quakers, most of the Highland Scots in the South, and many Iroquois Indians.[1] Many people with close business connections to Britain who lived in coastal towns remained loyal. Loyalists were most often people who were conservative by nature or in politics, valued order, were fearful of 'mob' rule, felt sentimental ties to the Mother Country, were loyal to the King or concerned that an independent new nation would not be able to defend themselves.[2]

Some escaped slaves became Loyalists. They fought for the British not out of loyalty to the Crown, but from a desire for freedom, which the British promised them in return for their military service. (Other African-Americans fought on the Patriot side, for the same motive). The story of the black Loyalists is outlined, with references, later in this article.

The longer the Revolutionary War went on, the more fluid and dynamic the "Patriot" and "Loyalist" categories became; and the larger the population became that did not fit neatly into either camp.[3] It is estimated that between 20 and 45% of the population were somewhere in the middle as "Trimmers' or neutrals who bent with the wind.

Arming the Loyalists in New England

As early as 1774, the Loyalist Edward Winslow met secretly with the Royal Governor of Massachusetts, Thomas Hutchinson, who approved Winslow's raising a "Tory Volunteer Company", whose purpose was to protect Loyalist families from roving mobs.

Before fighting began, Colonel Thomas Gilbert of Massachusetts had already raised the first Loyalist military unit. This was a force of three hundred men, armed by the British. Gilbert stored muskets, powder and bullets in his home. Shortly thereafter, Brigadier General Timothy Ruggles formed a Loyalist military unit called the "Loyal American Association", also in Massachusetts. Loyalists in New Hampshire also were arming.[4]

However, Patriots were arming and drilling all over New England, and outright revolution broke out on April 19, 1775, with the battles of Lexington and Concord, near Boston.

The war begins

Loyalists were present at the outskirts: British general Lord Hugh Percy's relief column, coming to the rescue of the redcoats retreating from Concord and Lexington, was accompanied by armed Loyalists in civilian clothes, members of a unit called Friends of the King. One of their number, Edward Winslow, had his horse shot out from under him, and was personally cited by Percy for bravery. Another, Samuel Murray, was captured but later released.

After the British were besieged inside Boston, Loyalist recruits inside the city continued to join the British side. After the Battle of Bunker Hill, Loyalist auxiliary units helped to maintain order inside the city. But that was all they were permitted to do, prior to the British evacuation of the city.[5]

The Patriot invasions of British Canada

The first organized Loyalist unit permitted to fight in a serious battle of the Revolution was Allan Maclean's 84th Regiment of Foot (Royal Highland Emigrants), who helped the British successfully defend Quebec after the American invasion of Canada in the last days of 1775.[6]

In 1776, Jonathan Eddy, a Nova Scotian who favoured the Patriot cause, got the blessing of George Washington to try to capture Nova Scotia for the Revolution. In November, 1776, Eddy, commanding a Patriot force of Indians, exiled Acadians and Maine Patriot militia, appeared at the gates of Fort Cumberland, Nova Scotia, and demanded its surrender. His plan was then to march on Halifax.

The fort was manned by the Loyalist Royal Fencible Americans. They repelled two assaults by Eddy's men, and were later joined by elements of the Royal Highland Emigrants, after which Eddy's invasion failed.[7]

Highland Loyalists in America

Highland Scots who had emigrated to America overwhelmingly favored the king over the Revolutionary cause. In the South, most of the Highland Scots organized quickly in the royal cause. But they early on suffered a devastating defeat. In early 1776, under the command of Brigadier General Donald Macdonald, a substantial force of North Carolina Loyalists, possibly as many as five thousand, began a march to the seacoast to join a British assault on Charleston. However, on February 27, 1776, they encountered a Patriot force at Moore's Creek Bridge. The Patriots waited until an advance guard of Loyalists had crossed the bridge, then annihilated them with devastating musket and cannon fire. The Loyalists were routed.[8]

The British invade New York

There were many Loyalists on Long Island and in New York City; the city was sometimes called "Torytown". In August, 1776, the British commander, William Howe, 5th Viscount Howe, landed a huge force of British and Hessian troops on Long Island, and won a major victory that drove Washington's army from the island and the city of New York. Many Long Island Loyalists, wearing pieces of red cloth on their hats to show their sympathies, landed with Howe, and participated in the fighting. At the end of the revolution, Long Island was the major staging area for many Loyalist emigrant ships departing for Canada.

As his men abandoned New York, Washington had wanted to burn the city to prevent the British using it, but Congress forbade it.[9]

In the aftermath of the British victory, many Loyalists came forth to be organized into uniformed Loyalist regiments. The British called these "provincial" regiments. Loyalist militia patrolled the streets of New York. Loyalist spies were extensively used to get information about Washington's dispositions. By the end of 1776, about eighteen hundred Loyalist soldiers had been recruited, most from Long Island, Staten Island, and Westchester County. Brigadier General Oliver De Lancey, a member of a prominent New York Loyalist family, organized De Lancey's Brigade. The King's American Regiment was formed.

The popular French and Indian War hero Robert Rogers organized a Loyalist regiment which was very effective. By the end of 1776, seven hundred of Rogers' Rangers were raiding Patriot outposts in Westchester. Recently unearthed documents indicate that it was Rogers and his Rangers who captured the famous Patriot Nathan Hale. There was a clash between Continental troops and Rogers' men at Mamaroneck in October, 1776. Rogers was retired soon after, but his unit, now called the Queen's Rangers, went on under the command of John Graves Simcoe, to fight throughout the Revolution.[10]

More Loyalists enlist

As Howe's army burst out of New York, new Loyalist regiments sprang into being. One was the New Jersey Volunteers (Skinner's Greens) who wore green coats, as did so many other Loyalist soldiers that they were often called "greencoats". The Prince of Wales' American Regiment was also raised. The British continued to recruit in southern New York, so much so that "Tory" New York eventually contributed more soldiers to the British side than to the Patriots.

These men became part of an ongoing civil war in New Jersey and New York. Loyalists now sought revenge for injuries inflicted upon them while Patriots had been in the ascendant. Cruelty on both sides was commonplace. Many died. Kidnappings were also common. Loyalists seized Richard Stockton, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, and after imprisonment and cruel treatment, he broke down, and signed an oath of allegiance to George III.

A British commander called the unceasing Loyalist raids "desolation warfare". Another scion of the Loyalist De Lancey family, James De Lancey, raised De Lancey's Cowboys, which raided Patriot houses and farms. The Patriots paid the De Lanceys back by burning down a De Lancey family mansion.[11]

At this early stage of the war, the Loyalist soldiers were primarily used for guard duties and keeping order, or distracted with civil warfare.

Burgoyne's invasion of New York and the Vermont Republic

On the northern frontier, Loyalists were often harshly treated, and they reacted in many instances by joining Loyalist military units, fearing that they could never return to their homes unless the British prevailed.

A number of influential Loyalists in northern New York quickly set to work building military forces. The King's Royal Regiment of New York was raised by the wealthy Loyalist Sir John Johnson. Large numbers of Iroquois Indians were recruited to the British side by the Mohawk leader Joseph Brant (Thayendenegea).[12]

In the spring of 1777, the British General John Burgoyne was ordered to invade northern New York by way of Lake Champlain. Burgoyne started south from Canada at the end of June, 1777, with a force of nearly eight thousand British regulars, German mercenaries, Loyalists, Indians and French Canadians. (There were few English-speaking Canadians at this time).

Burgoyne's plan called for the British Lieutenant Colonel Barry St. Leger, commanding a force of eighteen hundred, to capture the Patriot Fort Schuyler (Fort Stanwix) at the head of the Mohawk Valley. The British besieged the fort. On August 6, 1777, a Patriot force of eight hundred men, commanded by Colonel Nicholas Herkimer, set out to relieve the Patriot garrison at the fort. Herkimer's strung-out Patriot column was ambushed near Oriskany by a force of Indians, Loyalist militia, and the Loyalist King's Royal Regiment of New York. The Patriots suffered heavy casualties in the ambush, and Herkimer was severely wounded. The dying Herkimer propped himself against a tree and continued to command his troops in a battle which saw very heavy losses on both sides. At one point, a column of Loyalists turned their green jackets inside out as a ruse, and got very close to Herkimer's men; this was followed by hand-to-hand fighting. The Indians finally fled, and the Loyalists retreated.[13]

Lieutenant Colonel Friedrich Baum's detachment of Hessian mercenaries, accompanied by Loyalists, Indians and French Canadians, was sent by Burgoyne in the direction of Bennington, Vermont. Their mission was to seize supplies. On August 16, 1777, the British column was met by a large Patriot force under John Stark. In the ensuing battle, many of the Loyalist, French Canadian and Indian positions were quickly overrun, and the defenders fled or were captured.[14] The Loyalist Queen's Loyal Rangers were shattered as a fighting force, with more than two hundred of their men killed, wounded or captured.[15] The Germans eventually surrendered, (and a relief force was driven off) in what was a major Patriot victory.

Burgoyne's invasion was now in serious trouble. His supplies were low, Loyalists were not rallying to the colors in the numbers expected, and a huge force of Patriots was gathering against him. At Saratoga, Loyalists, Indians and French Canadians acted as scouts and sharpshooters for the British, but the fighting ended with a decisive defeat for the royal cause—the surrender of Burgoyne and his army on October 17, 1777.[16]

The Loyalist and Indian raids in New York and Pennsylvania

The British general Guy Carleton, impressed by the ambush at Oriskany, authorized John Butler to raise eight more companies of Loyalist Rangers, "to serve with the Indians, as occasion shall require". This unit was Butler's Rangers.[17] Butler's headquarters were established at Fort Niagara. This gave the Loyalists access to the river valleys of northern New York.

The British now decided that raids upon frontier settlements were the correct path to follow. An early raid was made in May, 1778, on Cobleskill, New York, where three hundred Loyalists and Indians, led by the Mohawk chief, Joseph Brant, defeated a small Patriot force of militia and Continental regulars, then burned homes, crops and barns.[18]

In late June, 1778, a mixed force of Indians and John Butler's Loyalist Rangers attacked the settlement in Wyoming Valley, in Pennsylvania. The raiders were resisted by a force of inexperienced Patriot militia. These were badly defeated. The Loyalists and Indians devastated the whole area. Reports indicated that some prisoners and fleeing Patriots were tortured and murdered. One historian has said, "The Tories [Loyalists] usually neither gave nor expected any quarter, and when this vengeful spirit was augmented by the Indian propensity for total war, the results were almost invariably grim."[19]

Now Loyalists and Indians swept through the Mohawk Valley in "endless raids". In November, 1778, a mixed force of Loyalists and Indians attacked settlements in Cherry Valley, New York. The Loyalist commander this time was Walter Butler, son of John. Again, there was enormous devastation, and many civilians were killed. A contemporary account depicts Joseph Brant stopping some of Butler's men from killing a woman and child with the words "... that child is not an enemy to the King, nor a friend to Congress."[20]

In retaliation for all this, George Washington ordered a full-scale attack by regular troops of the Continental Army. Generals John Sullivan and James Clinton and Colonel Daniel Brodhead, at the head of forty-six hundred men, advanced on the Indians, their objective "the total destruction and devastation" of the Iroquois settlements.[21] A substantial blow to the pro-British Indians was achieved.[22]

The British turn to the South

Throughout Lord Howe's campaigning in New Jersey and Pennsylvania, many uniformed Loyalist troops had continued to be used for guard duties, keeping order and foraging. Many saw action too. John Graves Simcoe and his Queen's Rangers executed a very successful raid on Patriot forces in the Battle of Crooked Billet, in May, 1778. At Brandywine, the Queen's American Rangers fought throughout the day, and sustained heavy casualties.[23]

But the British were planning a new strategy. The already-enlisted Loyalist soldiers from the North, and the not-yet-mobilized Loyalists of the South were about to go into battle on a larger scale.

The British were being told that large numbers of Loyalists eagerly awaited their arrival in the South. It was decided to tap this supposed loyal sentiment. Slowly, British sentiment shifted toward a major Southern effort. To begin with, Lieutenant Colonel Archibald Campbell, in command of a British regiment, two Hessian regiments, four Loyalist battalions and artillery, was dispatched to Georgia. On December 29, 1778, the Patriots were badly defeated near Savannah, with New York Loyalists proving invaluable in the victory. Savannah was soon in British hands.[24]

The British then moved against Augusta, Georgia. They were assisted by a Georgia Loyalist named Thomas Brown. Son of a wealthy family, Brown had in the summer of 1775 been confronted by a group of Patriots who demanded that he swear allegiance to the revolutionary cause. Refusing, Brown shot and wounded the Patriot leader. The other Patriots fractured Brown's skull, partially scalped him and tarred his legs and held them over a fire, burning off two of his toes. (He was known thereafter to the Patriots as "Burntfoot Brown". Two weeks after these injuries, Brown was in South Carolina, recruiting hundreds of men to the King's cause. He became a scourge to the Patriots. Brown's East Florida Rangers, some of the New York Volunteers, and the Carolina Royalists marched in Lieutenant Colonel Archibald Campbell's British column when it marched on and took Augusta. Campbell said jubilantly that he had taken "a stripe and star from the rebel flag" [25]

The British Southern strategy called for the large-scale enlistment of Southern Loyalists. The British hoped that, with the aid of the Northern Loyalist regiments now arriving in the South, the Southern Loyalists could maintain control over their neighborhoods, slowly enlarging the scope of British domination. This policy was energetically pursued.

An early setback for the policy lay in the fate of the eight hundred North and South Carolina Loyalists who gathered at the Broad River under Captain Boyd. These Loyalists marched toward the Savannah, inflicting a great deal of devastation. On February 14, 1779, at Kettle Creek, Georgia, a Patriot force caught up with them, and in the ensuing battle, the Loyalists were defeated. Five of their leaders were hanged for treason.[26]

But the recruitment of Loyalists proceeded. The British position in the South was strengthened when British and Loyalist forces repelled a French and Patriot siege of Savannah in the fall of 1779, with great loss of life to the besiegers.

Early British victories in the South

The British besieged Charleston in an arduous campaign. A crucial contribution was made by Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton, the English commander of a Loyalist unit called the British Legion. In a night attack on April 14, 1780, Tarleton took Monck's Corner, South Carolina, a strategic victory which helped seal off the Patriot garrison of Charleston from help or escape. Charleston's surrender to the British on May 12, 1780 was a disaster to the revolutionary cause. Over twenty-five hundred Continental regulars and huge supplies of Patriot weapons and ammunition were lost. [27] Another leader of Loyalists, the Scotsman Patrick Ferguson, commanded a force called the American Volunteers, who formed part of the army which took Charleston. [28]

Now the civil war in the South widened. Banastre Tarleton's British Legion, sometimes called the Loyal Legion, was a force consisting mostly at first of Pennsylvanians. It was quickly augmented by volunteers from the South. At one point the Legion grew to nearly two thousand men. On May 29, 1780 Tarleton and his men defeated a Patriot force under Abraham Buford at Waxhaws, South Carolina. After Buford refused to surrender, the Legion charged. Tarleton's horse was shot from under him; he mounted another. Buford and eighty or ninety men escaped. Over three hundred Patriots were killed or wounded, an almost incredible percentage of those engaged. The story soon spread that the Loyalists had bayoneted many of the wounded and those trying to surrender. Patriots began to speak bitterly of "Buford's Quarter," or "Tarleton's Quarter," meaning none.

In the civil war in the South, both sides resorted to the burning of farms and homes, torture, and summary execution on a huge scale.[29]

In the Battle of Ramsour's Mill, North Carolina, on June 20, 1780, the combatants on both sides were untrained militia, few if any in uniform. The battle was fought between neighbors, close relations and personal friends. More than half the Patriots in the battle were killed or wounded, and Loyalist casualties were very high. After the battle, the Loyalists retreated and left the Patriots in possession of the field. A prominent historian called this "... the most desperate engagement of the war in terms of the proportion of casualties to men involved on each side".

The same historian has written, "The battle of Ramsour's Mill... was the archetypal battle of the 'new man,' the American, whether Tory or patriot; it was the supreme military expression of individualism... here every man was a general in the sense that he fought, to a very large degree, in response to his own best judgment of what should be done."[30]

British fortunes reached their high point in August, 1780, when Lord Charles Cornwallis's force of British regulars and Loyalists inflicted a seemingly-decisive defeat on Patriot forces at the Battle of Camden. A substantial number of Cornwallis's three thousand men were Loyalists—North Carolina Loyalist regulars and militia, a Northern unit called the Volunteers of Ireland, and the infantry and cavalry of the British Legion. Lord Cornwallis did not oppose his Loyalists to the Patriot militia, and send his British regulars against the Continental regulars. Instead, the Loyalists faced the Patriot regulars, and the British attacked the inexperienced Patriot militia, routing them, exposing the Patriot flank, and causing the collapse and total rout of the whole Patriot army.[31]

The huge British success at Camden diverted attention from a Patriot victory at Musgrove's Mill, South Carolina, fought about the same time. This little-known battle was important. In it, an outnumbered force of Patriots confronted a force of Loyalist regulars and militia. The battle was fierce and protracted, but the frontier Patriot sharpshooters inflicted heavy casualties on the Loyalists, who were completely defeated. This success did much to hearten backwoods Patriots in the aftermath of so many British successes. [32]

The Patriot sharpshooters fared less well in September, 1780, in an attempt to retake Augusta from the British. The Patriot Colonel Elijah Clarke led nearly seven hundred mountain riflemen against a Loyalist garrison of only one hundred and fifty, accompanied by a few score Indians. But the Augusta garrison was commanded by Thomas "Burntfoot" Brown of Georgia, a resourceful man. Judging Augusta indefensible, Brown drove Clarke's men back by artillery fire, and the Loyalists then forced their way by bayonet right through the Patriot force, to the top of nearby Garden Hill. Brown held out for four days. Eventually the Patriots ran out of ammunition, but they cut off the Loyalists' water supply. Brown, in agony after yet another leg wound, ordered his men's urine be kept and cooled, and took the first drink himself. Eventually Brown's garrison was relieved by Loyalists, and the Patriots retreated. [33]

Continuing Loyalist and Indian raids

Despite Washington's retaliation, the Loyalist and Indian raids on the frontier intensified. The first order of business for the British was to destroy the Oneidas, the one tribe in New York which supported the Patriot cause. Supported by British regulars and Loyalists, the Mohawks, Senecas and Cayugas destroyed the Oneida settlements, driving the Oneidas away and destroying their usefulness as an early warning line to alert defenders that the Indian and Loyalist raiders were coming.

Now Joseph Brant's Loyalist Indians devastated the frontier. In May, 1780, Sir John Johnson, commanding four hundred Loyalists and two hundred Indians, attacked many settlements in the Mohawk Valley. Brant then led his men down the Ohio, where he ambushed a detachment of troops under the command of George Rogers Clark.[34]

In the autumn of 1780, Johnson, commanding over a thousand Loyalists and Indians, launched another series of raids.[35]

Revenge was soon to follow, however. In 1781, after renewed raids, the Patriot leader Marinus Willett inflicted two defeats on the Loyalists and Indians. The second one was won over a force composed of eight hundred Loyalists and British regulars, accompanied by a much smaller force of Indians. This Patriot victory was decisive, and in it Walter Butler was killed. Marinus Willett's son said that Butler "had exhibited more instances of enterprise, had done more injury, and committed more murder, than any other man on the frontiers." Yet only six years before, he had been a lawyer in Albany, a member of a prominent family, a handsome, graceful man.[36]

The tide turns in the South

After Camden, Banastre Tarleton's and Patrick Ferguson's Loyalist forces had been in the ascendant. An example was Tarleton's victory over Patriot raiders at Fishing Creek, shortly after the battle at Camden.[37]

Then a turning point came at King's Mountain, on the border of the Carolinas, on October 7, 1780. Major Patrick Ferguson commanded a Loyalist force which was enjoying success in pacifying northern South Carolina for the royal cause. But a Patriot force of over one thousand "over-the-mountain men", pioneers from the westernmost settlements, experts in the use of the rifle, was coming after him. Augmented by several hundred Patriot militiamen from the Carolinas, this force cornered Ferguson at King's Mountain.

Ferguson had nine hundred Loyalist troops, made up of Southern militia and detachments from three Northern units--the King's American Rangers, the Queen's Rangers and the New Jersey Volunteers. Ferguson, inventor of a breech-loading rifle, found himself in a situation where his Loyalists were armed with muskets, and the Patriots with rifles, whose range was greater. A series of Loyalist bayonet charges drove the over-the-mountain men back several times, but eventually Loyalist resistance collapsed. Ferguson was killed. After the Loyalist force surrendered, the frontiersmen fired point-blank into a mass of Loyalist prisoners, killing nearly a hundred of them. Other Loyalists were summarily hanged. Some Loyalists escaped, but Ferguson's force was completely destroyed, a huge blow to the British.[38]

Now a defeat lay in store for another commander of Loyalists—Banastre Tarleton. On January 17, 1781, Tarleton went into action against the Patriot commander Daniel Morgan at Cowpens, South Carolina. Tarleton had over five hundred Loyalist infantry and cavalry of his British Legion, along with Loyalist militia and British regulars. His eleven hundred men slightly outnumbered Morgan's force, which consisted of Continental regulars and Patriot militia. The culminating moment of the battle occurred when the Patriot right gave way. The Loyalists thought that the Patriots were panicking, as they had at Camden. The Loyalists began to advance, and Tarleton ordered one of the impetuous charges for which the British Legion was famous. The Loyalists ran into massed Patriot fire, and then were taken on their flank by an expertly timed Patriot cavalry charge. It was all over very quickly. Tarleton and a few others escaped, leaving behind a hundred killed, and over eight hundred captured, including two hundred and twenty-nine wounded. Another important Loyalist force had been nearly destroyed.[39]

Another Loyalist defeat followed on February 24, 1781, at the Haw River, North Carolina. The Patriot commander Colonel Henry Lee (father of Robert E. Lee) was in pursuit of Tarleton, who was moving around the area with a renewed force, recruiting Loyalists. A force of four hundred Loyalists under John Pyle was moving to join Tarleton. But they made a disastrous mistake. Lee's men wore green coats, like Loyalists, rather than the usual Patriot blue. Pyle and his men rode up to meet what they assumed was Tarleton's Legion (Tarleton himself was only a mile away). Lee actually grasped Pyle's hand, intending to demand surrender. At the last minute, a Loyalist officer recognized the ruse and ordered his men to open fire. Ninety Loyalists were then killed and many more wounded; not a single Patriot died.[40]

On March 15, 1781, the British won a victory at Guilford Court House, North Carolina. Tarleton's cavalry was present. This was a tactical British victory with huge losses, which made it clear that British power in the South was waning. On April 25, 1781, another battle was fought at Hobkirk's Hill, near Camden. An American historian has called Lord Rawdon's outnumbered nine-hundred-man British force "a motley collection of Loyalists stiffened by a few regulars".[41] In fact, the British force consisted mostly of Northern Loyalist units--the King's American Regiment, the New York Volunteers and the Volunteers of Ireland-- and a South Carolina militia unit. The Patriot forces were eventually driven from the field.[42] But British power in the South continued to decline.

Now the forts established by the British and manned by Loyalists fell to the Patriots, or were abandoned one by one. A major engagement was fought at Fort Ninety-Six, South Carolina, from May 22 to June 19, 1781. The defenders consisted of five hundred and fifty Loyalists, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel John Cruger, a New Yorker. Three hundred and fifty of Cruger's men were members of regular Loyalist regiments; the rest were South Carolina Loyalist militia. The besiegers consisted of a thousand Patriots under Nathanael Greene. The Patriots at Ninety-Six used classic siege warfare techniques, inching ever closer to the Loyalist fortifications. Cruger ordered attack after attack on the Patriot lines, to try to disrupt the work. Exhorted to surrender, Cruger defied Greene's "promises or threats". Hearing that Lord Rawdon was marching to the relief of the fort, Greene ordered a general attack. It was a failure. One hundred and eighty-five Patriot attackers were killed or wounded. In a few more days, the fort would have fallen, but Greene broke off the engagement and retreated.[43]

The story of the Ninety-Six siege from the Loyalist point of view is told in detail in the classic novel Oliver Wiswell, by Kenneth Roberts.

The last major battle in the South took place on September 8, 1781, at Eutaw Springs, South Carolina. The British forces included Loyalist units commanded by John Coffin and John Cruger (still fighting after abandoning Fort Ninety-Six.) After a long, bloody struggle the Patriots retreated. But the battle did nothing to halt British decline in the South. [44]

The British and Loyalists in the South had shown energy and courage. It had not been enough. As one historian said, "A vast area, far from the center of the stage in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, was seized by the British. The patriots, without anything but hindrance from their French allies, met initially with disastrous setbacks but finally, in a campaign that is a textbook study in the tactics and techniques of partisan warfare, recovered, for all practical purposes, the Carolinas and Georgia."[45]

By the time of the battle at Eutaw Springs, Cornwallis and the main part of his army had marched into Virginia. During the early part of his Virginia campaign, Cornwallis used the Loyalist cavalry as his "eyes." Tarleton's Legion had, after its defeats in the Carolinas, grown back to eight hundred men, mounted on Virginia thoroughbred hunters. Their defeats had robbed them of some of the dash they'd previously shown. But they remained dangerous. Cornwallis sent Tarleton and his men on a lightning raid against the Virginia Patriot government at Charlottesville, Virginia. The aim was to capture the House of Burgesses, and the Governor, Thomas Jefferson. Tarleton moved with his usual swiftness, by back roads. As his men passed the Cuckoo Tavern, near Louisa, Virginia, they were overheard by a celebrated Patriot marksman and horseman named Jack Jouett. He saw through a window, by faint moonlight, the hated Tory cavalry trotting past. Jouett set out with great success to arouse the neighborhood. He woke up Jefferson and his family at Monticello. Mrs. Jefferson and the children were removed to safety. Jouett also warned the Patriot legislators. When Tarleton stopped at the plantation of a Patriot, Mrs. Walker, she reputedly deliberately delayed Tarleton and his Loyalist officers with an enormous breakfast of salt herring, salt beef and johnnycake. But then the Legion lunged at Charlottesville. They moved so fast that they captured a thousand Patriot muskets, four hundred barrels of gunpowder, seven members of the House of Burgesses, and very nearly, Jefferson himself. At about the same time, John Graves Simcoe and his Loyalist Rangers moved against the Patriot commander von Steuben, who was guarding Patriot supplies. Steuben fled, and the stores were captured by the Loyalists. [46]

But the endgame was at hand. Cornwallis moved to fortify himself at Yorktown. A huge force of Patriot and French soldiers moved against him, and Cornwallis's surrender on October 19, 1781 proved decisive in winning the war.

British-Loyalist raids

Minor Loyalist raids continued well after the surrender at Yorktown.

On July 2, 1779, William Tryon, a former royal governor, assembled a force of twenty-six hundred regulars, Hessians, and a major Loyalist regiment, the King's American Regiment. This force attacked New Haven, Connecticut. Colonel Edmund Fanning of the King's Americans dissuaded Tryon from burning Yale College and the town (Fanning was a Yale graduate). The sacking of New Haven gave birth to a Yale legend. Napthali Daggett, a former college president, was caught firing at the royal troops. A British officer asked him if he would fire on them again if his life was spared. "Nothing more likely," said Daggett, who was promptly bayoneted. But a former student of his, William Chandler, a Loyalist officer, saved his life. Tryon's force went on to sack and burn the nearby town of Fairfield, then the town of Norwalk.[47]

William Franklin was the Loyalist son of Benjamin Franklin, and the former royal governor of New Jersey. One historian has called Franklin "one of the most dangerous Tories in America."[48] Franklin's unit, the Associated Loyalists, launched a series of raids in New Jersey.[49] On one occasion, the Associated Loyalists seized a well-known Patriot leader, Joshua Huddy. The Loyalists wanted revenge for the death of Philip White, a Loyalist who had been captured by Patriots and shot while trying to escape. The Loyalists hanged Huddy, leaving him swinging with a message pinned to his breast, reading in part "... Up goes Huddy for Philip White."[50]

A document dated 1 May 1782 in the papers of George Washington records various violent acts taken against people in parts of New Jersey, such as Monmouth County, some of whom are specifically identified as being Loyalists, and among those listed is Philip White for which the paper says:[51]

Philip White Taken lately at Shrewsburry in Action was marched under a guard for near 16 Miles and at Private part of the road about three Miles from Freehold Goal (as is asserted by creditable persons in the country) he was by three Dragoons kept back, while Capt. Tilton and the other Prisoners were sent forward & after being stripped of his Buckles, Buttons & other Articles, The Dragoons told him they would give him a chance for his Life, and ordered him to Run—which he attempted but had not gone thirty yards from them before they Shot him.

Philip White's brother, Aaron White, was captured with him, and although originally said that Philip was shot after trying to escape later recanted inasmuch as his statement had been made under threat of death and that his brother had actually been murdered in cold blood.[52]

The last major event of the war in the North came in September, 1781, when Benedict Arnold, now a British general, led a mainly Loyalist force of seventeen hundred men, which included Arnold's own American Legion, some New Jersey Volunteers and other Loyalists, in burning down New London, Connecticut.[53] This was the last of the major Loyalist raids in the North.

The Black Loyalists

The Revolution offered an opportunity for large numbers of slaves to fight, and many did, on both sides, in the hope of earning their freedom.[54] It has been suggested that two revolutions went on at once—the Patriot one against the British, and a second one fought by blacks for their freedom.[55]

Throughout the war, the British repeatedly offered freedom to those slaves who would join their side. One historian has said, "Thousands of blacks fought with the British."[56] One American historian has gone so far as to assert that the British position on black civil rights during the Revolution was morally superior to that of the Patriots. [57]

The story began when Lord Dunmore, the former royal governor of Virginia, on November 7, 1775, proclaimed freedom for all slaves (or indentured servants) belonging to Patriots, if they were able and willing to bear arms, and joined the British forces. One historian has said, "The proclamation had a profound effect on the war, transforming countless slaveholders into Rebels and drawing thousands of slaves to the Loyalist side."[58] Within a month of the proclamation, more than five hundred slaves left their masters and became Loyalists. The Ethiopian Regiment was raised, and put on uniforms with "Liberty to Slaves" across the chest. British regulars, white Loyalists and the Ethiopian Regiment attacked Great Bridge, near Norfolk, Virginia. The attack failed, and thirty-two captured blacks were sold by their captors back into slavery.[59]

Some of the Ethiopian Regiment escaped with Dunmore to New York shortly after the city was captured by the British in 1776. There the regiment was disbanded, but some of its men joined the Black Pioneers. This unit had been formed by the British general Henry Clinton, in North Carolina, from slaves responding to Dunmore's proclamation. (A pioneer in the British Army was a soldier who built bridges and fortifications.)[60]

In August 1775, South Carolina Patriots executed Thomas Jeremiah for treason. Jeremiah was a freed black man allegedly sympathetic to the British. Within three months of his death, five hundred blacks, a tenth of the black population of Charleston, had escaped to join the British forces, and both black and white Loyalists were raiding Patriot plantations.[61]

At the end of 1775, the British officer Captain William Dalrymple proposed that blacks be used as "irregulars"—that is, for what we now call guerilla warfare.[62] As the war ground on, an increasing number of blacks did indeed fight as Loyalist irregulars, or with the regular British forces.

Estimates of the number of slaves who escaped to the British range from twenty thousand to one hundred thousand.[63] Thomas Jefferson estimated that thirty thousand slaves fled their masters just during the brief British invasion of Virginia in 1781.[64] Recent studies show that black soldiers fought in the British forces in large numbers, and one historian has said, that "... black soldiers were the secret of the imperial [British] army in North America."[65]

In Massachusetts, the British organized both all-black and multi-racial units. In 1779, Emmerich's Chasseurs, a Loyalist unit in New York, included blacks who raided the Patriots. There were black soldiers in De Lancey's Brigade in Savannah. There were blacks in the Royal Artillery units in Savannah, and black dragoons (cavalry). There were also large numbers of black pioneers and other non-combatant troops. At one point, ten per cent of the British forces at Savannah were black. There were substantial numbers of black soldiers in the British forces at Charleston, and analyses of British records show that blacks were represented in British units in Rhode Island at about the same time (1779).[66]

One of the most prominent black Loyalists was an escaped slave named Tye. This young man escaped in 1775 from his master in New Jersey, at that time a colony where slavery was legal. In Virginia, Colonel Tye joined Dunmore's regiment. After the regiment was disbanded, Tye fought on the British side in the battle of Monmouth. Colonel Tye, so-called by the British, then founded a unit which the British called the Black Brigade. The Brigade raided Patriot homes and farms in New Jersey, gathered intelligence for the British, kidnapped Patriot leaders, and gathered firewood and provisions for the British Army. Colonel Tye's men became a scourge to the Patriots. They were headquartered in a timber-built fortress at Bull's Ferry, New Jersey. George Washington sent a thousand troops against the fortress. A force of black and white Loyalists fought them off after an assault, and the raids went on. Colonel Tye finally died after being wounded in an assault by his men on the home of Joshua Huddy, the Patriot later hanged by William Franklin's Associated Loyalists.[67]

From at least 1776 through 1779, other black Loyalists were heavily involved in raids against Patriot forces in New Jersey.[68]

An American historian has said about the war in the South, "The more intelligent and articulate [sic] of the freed slaves were quite frequently used by the British as guides in raiding parties or assigned to the commissary..."[69] (to help round up provisions). Eliza Wilkinson, daughter of slave-holding Patriots, recorded a Loyalist raid of which she thought one of the most terrible features was the presence of "armed Negroes".[70] Battalions of blacks fought in the successful defense of Savannah against a French and Patriot siege at the end of 1779. One British observer wrote, "Our armed Negroes [were] skirmishing with the rebels the whole afternoon", and, later, "... the armed Negroes brought in two Rebel Dragoons and eight Horses, and killed two Rebels who were in a foraging party."[71] When Lord Cornwallis invaded Virginia in 1781, twenty-three of Jefferson's slaves escaped and joined the British forces.[59] It was said that two or three thousand black Loyalists were with Cornwallis in the Carolinas.[72]

British treatment of the black Loyalists was not uniform. The black soldiers were often housed in crowded, disease-ridden conditions.[69] On one occasion, British transport ships were leaving a Southern port for the West Indies, and were not able to take on all the blacks who wanted to escape. The black Loyalists clung to the sides of ships (risking capsizing them) until their fingers were chopped off by British soldiers. Others were abandoned on an island where twenty years after the Revolution, the ground was littered with their bones.[73]

When the war ended, the question arose as to what would happen to the Loyalists. The British were willing and anxious to reward white Loyalists and their families by helping them escape from the vengeance of Patriots. This particularly included those who had fought on the British side.

But what would happen to the blacks? As the fighting ended, escaped slaves were flooding into British-occupied New York City. Even there, blacks lived in terror of their former owners. Boston King, an escaped slave who had fought with the British, said "... we saw our old masters coming from Virginia, North Carolina, and other parts, and seizing upon their slaves in the streets of New York, or even dragging them out of their beds."[74]

Then the British government, having promised emancipation to all former slaves who fought for it, concluded a peace treaty ending the war. The treaty said, in article 7, that the British were to leave the United States "without ... carrying away any Negroes".

Many of the senior British officers in North America refused to comply with article 7. The British general Sir Guy Carleton (later Lord Dorchester), who commanded in New York City, believed that any black American who had served the mother country was not property; he (and his family) were British subjects. In defiance of the plain language of the treaty, (and of his own political masters in London), he began to issue passes which allowed the black bearer to go to Nova Scotia, or wherever else the freed black thought proper.[75] In May, 1783, George Washington met with Carleton. Washington protested about the British policy of carrying escaped slaves away. Carleton told Washington that the British were compiling a list of all the blacks who were being helped to escape, called the Book of Negroes.[76] A contemporary account states that "Sir Guy Carleton observed that no interpretation could be put upon the article [article 7 of the peace treaty] inconsistent with prior [promises] binding the National Honor which must be kept with all colors", and Carleton rebuked Washington for the suggestion that a British officer would consent to a "notorious breach of the public faith towards people of any complexion".[77] One black Loyalist who was eventually evacuated by Carleton had belonged to Thomas Jefferson, and three to George Washington.[78]

Eventually, nearly three thousand ex-slaves were evacuated by Carleton to Nova Scotia. One of their leaders there was Colonel Stephen Blucke, commander of the Black Brigade after Colonel Tye's death. Some eventually went on to Sierra Leone. Boston King and his wife were among them. Many remained in Nova Scotia.[79]

Nor were Carleton's evacuees from New York City the only black Loyalists to escape from the United States. Thousands of other blacks escaped to Canada by other means, many on ships leaving Charleston or Savannah. Others escaped to British Florida. A total of between ninety-one hundred and ten thousand four hundred black Loyalists eventually found refuge in Canada.[80]

The fate of the Loyalists

The majority of the 400,000 to 500,000 Loyalists remained in the United States after the British left. Those who were in Loyalist combat units, and non-combatant Loyalist families who had very visibly aided the British cause, and/or were unshakably loyal to Britain, mostly left. The largest number became the foundation of the English-speaking Canadian community.[81] According to recent estimates, about 62,000 Loyalists at a minimum left the United States by 1784: 46,000 to Canada, 8000-10,000 to Great Britain and the rest to the Caribbean. 5,090 whites and 8,385 blacks went to Florida, but almost all moved on after it was returned to Spain in 1784: 421 whites and 2,561 blacks returned to the States.[82]

The greater part of Loyalist emigration to Canada went to Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. There were at least two waves of American immigration shortly after the Revolution to what is now Ontario, then Upper Canada. The first wave were the wartime Loyalists, who in the early 1780s, went to the southern and eastern parts of the Niagara Peninsula. (Others went to the Eastern Townships in Quebec.) The emigrants to Ontario numbered approximately 6,600, not counting the Native American Iroquois. Small numbers of dedicated "Tories" continued to arrive in Upper Canada during the 1780s either as individual families or in small groups from the Mid-Atlantic States. In the second wave, 30,000 Americans, attracted by promises of land and low taxes in exchange for swearing allegiance to the King, went in the 1790s to the western Niagara Peninsula. Referring to this later group of land-seeking immigrants, Canadian historian Fred Landon concludes that, "Western Ontario received far more land-seekers than Loyalists."[83] However, the first wave, the dedicated Loyalist soldiers and families who came shortly after the Revolution, had a much greater influence on the political and social development of Ontario.

As to the Loyalists who went to England, their story was sometimes not as happy as they had no doubt dreamed. "Transplanted Americans were treated as Americans, not former or new Britons," and, "Some wealthy Loyalists chose exile in England, though they knew Loyalists were not welcome there."[84]

As to the Loyalists who remained within the United States, Loyalists were a minority in every state and in most communities. This differentiated them from the assertive, vocal, white pro-Confederate majorities in the South after the Civil War, who proudly proclaimed their Confederate heritage. After the Revolution, Loyalists and their descendants, prudently, rarely drew attention to themselves. An example of some who did is the Tiffany family, originally of Connecticut, who donated the diary of a Loyalist ancestor to the Library of Congress in 2000. The diary indicated that in fact the Patriot hero Nathan Hale was captured by Robert Rogers and his Loyalists, a narrative not known before. [85]

Remaining in the United States after the Revolution, or leaving and later returning, were not options for some of the Loyalists. Those who had fought for, or supported, the King sometimes rejected the new republic. The figure of a minimum of 62,000 Loyalist emigrants is given above. Another, higher, estimate is given in an American work dated 2010, which states that about one hundred thousand Loyalists were evacuated, most of them to Canada.[86] The numbers of those who left, and who stayed away, are debatable. For more information on this topic, see Loyalist (American Revolution), United Empire Loyalist, and Expulsion of the Loyalists.

In Canada, Loyalists of each regiment were usually given land in the same area so that soldiers who fought together could remain together. Allocations also depended on the Canadian port at which a regiment arrived. Thus, the King's Royal Regiment of New York, Butler's Rangers, Jessup's Corps, the King's Rangers and Joseph Brant's Iroquois got land in what is now Ontario; part of De Lancey's Brigade, the Pennsylvania Loyalists, the King's American Dragoons, the New Jersey Volunteers, the Royal Fencible Americans, the King's Orange Rangers and others were given land in what is now New Brunswick. Other Loyalists settled in Nova Scotia and Quebec.[87]

The defeated Tories of the Revolution became the United Empire Loyalists of Canada, the first large-scale group of English-speaking immigrants to many parts of that country, and one which did much to shape Canadian institutions and the Canadian character.

Loyalists became leaders in the new English-speaking Canadian colonies. John Graves Simcoe, commander of the Queen's Rangers, became the Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada (Ontario), and the city of Brantford, Ontario is named for the Loyalist Indian leader Joseph Brant. There is a bust of John Butler of Butler's Rangers at the Valiants Memorial in Ottawa.

The pro-Loyalist tradition in Canada has been summed up by an American historian: "Many Canadians believe that their nation's traditional devotion to law and civility, the very essence of being a Canadian, traces back to being loyal, as in Loyalist."[86] This Canadian self-image is reflected in the British North America Act, (1867), the founding Canadian constitutional document, which defines the aims of the new Dominion as "peace, order and good government"--contrast with "life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness."

8-10,000 Loyalists went to England, including hundreds of former slaves and Anglican clergy.[88] Eventually about 25% returned over the following decades.

Popular culture

By the time of the Civil War, American popular hostility to the Loyalists was fading, to be replaced by a vague memory of a few malcontents who for some reason could not accept the Revolution. Yet Loyalists appear in American popular culture. In Stephen Vincent Benet's short story "The Devil and Daniel Webster", Webster in his quarrel with the devil demands "an American jury", and gets one containing the Loyalist officer Walter Butler. In the book and film Drums Along the Mohawk, Loyalists are shown looting and burning with their Indian allies. The Disney television series The Swamp Fox (about the Patriot leader Francis Marion) showed Loyalists as cowardly guns-for-hire and was condemned by the Canadian House of Commons. The 1985 Al Pacino film Revolution depicts a rich Loyalist family named the McConnahays, whose youthful daughter falls for Pacino and the Patriot cause. The film The Patriot has a British character, Tavington, based on Banastre Tarleton. In history, Tarleton's men were mostly Loyalists. In the film, one, Captain Wilkins, is given a chance to declare his British allegiance at the beginning of the film, and is seen helping Cornwallis to the end.

The novel Oliver Wiswell, by the American historical novelist Kenneth Roberts, tells the whole story of the Revolution from the Loyalist side. Roberts did not portray his Loyalist hero as eventually seeing the error of his ways and returning to the American fold. Instead, the book depicts Oliver Wiswell from his new home in Canada (which he calls "land of liberty") as still being hostile to the revolution and its leaders. Another American historical novelist, Bruce Lancaster, also depicted Loyalists, although from a more conventional condemnatory point of view.

Two novels at least deal with the story of the black Loyalists. One is Washington and Caesar by Christian Cameron, which tells the story of a black Loyalist fighting in the British forces. The Canadian novel The Book of Negroes, by Lawrence Hill, depicts an enslaved black woman who helps the British and escapes with their help.

References

- Middlekauff, Robert, The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789, Oxford University Press, 1982, pp. 549-550

- Leonard Woods Labaree, Conservatism in Early American History (1948).

- Ellis, Joseph J., American Creation: Triumph and Tragedies at the Founding of the Republic, Vintage Books, 2007, p. 75

- Thomas B. Allen, Tories Fighting for the King in America's First Civil War Harper, 2010, pp. 19-20; pp. 34-36

- Allen, p. 61; p. 74

- Allen, pp. 100-102

- Allen, pp.106-108

- Smith, Page, A New Age Now Begins A People's History of the American Revolution (Vol. One), McGraw-Hill, 1976, pp. 624-625

- George C. Daughan (2016). Revolution on the Hudson: New York City and the Hudson River Valley in the American War of Independence. W. W. Norton. pp. 84–85. ISBN 9780393245738.

- Allen, pp. 157-183

- Allen, pp. 184-208

- Allen, pp.214-221

- Smith, Page, A New Age Now Begins A People's History of the American Revolution (Vol. Two), McGraw-Hill, 1976, pp. 891-912

- Smith, (Vol. Two), pp. 915-919

- Allen, pp. 229-230

- Allen, pp. 230-234

- Allen, p. 252

- Allen, pp. 252-255

- Smith, (Vol. Two), pp. 1150-1158

- Smith, (Vol. Two), pp. 1159-1162

- Smith, (Vol. Two), p. 1163

- Allen, p. 264

- Allen, p. 235-251

- Middlekauff, pp. 434-435

- Allen, pp. 278-279

- Smith, (Vol. Two), pp. 1309-1311

- Middlekauff, pp. 448-449

- Allen, p. 281

- Allen, pp. 281-287

- Smith, (Vol. Two), pp. 1399-1404; p. 1485

- Middlekauff, pp. 454-457

- Smith, (Vol. Two), pp-1404-1405

- Smith, (Vol. Two), pp.1423-1424

- Smith, (Vol. Two), pp. 1178-1182

- See Watt, Gavin K., The Burning of the Valleys Daring Raids From Canada Against the New York Frontier in the Fall of 1780, Dundurn Press, 1997

- Smith, (Vol. Two), pp. 1184-1189

- Smith, (Vol. Two), pp.1419-1420

- Smith, (Vol. Two), pp. 1419-1434

- Middlekauff, pp. 470-476

- Smith, (Vol. Two), pp. 1470-1472

- Smith (Vol. Two), p. 1492

- Smith (Vol. Two), pp. 1486-1495

- Smith (Vol. Two), pp. 1502-1506

- Middlekauff, pp 493-495

- Smith, (Vol. Two), p. 1507

- Smith, (Vol. Two), pp. 1631-1633

- Allen, pp. 302-306

- Allen, p. 295

- Allen, pp. 307-320

- Smith (Vol. Two), p. 1750

- "To George Washington from Not Assigned, 1 May 1782 (Early Access Document)". The Papers of George Washington. Founders Online. 1 May 1782. Archived from the original on 5 June 2020.

- "Perfidious America". The Economist. 20 December 2014. pp. 64–66. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

Accounts of his death differ: his brother Aaron, captured with him, signed an affidavit attesting that he was killed while trying to escape. Aaron later recanted, claiming that his captors had threatened to kill him unless he signed; the truth, he now maintained, was that the American militiamen had executed Philip White in cold blood.

- Allen, pp. 320-321

- For a full account, see Gilbert, Alan, Black Patriots and Loyalists Fighting For Emancipation in the War For Independence, University of Chicago Press, 2012

- Gilbert, p. 6

- Zinn, Howard, A People's History of the United States, Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 2005, p. 88

- Gilbert, p. xi

- Allen, p. 155

- Allen, pp. 154-155

- Allen, pp.172-173

- Gilbert, pp. 39-45

- Gilbert, p. 29

- Gilbert, p. xii

- Gilbert, p. ix

- Gilbert, p. 261

- Gilbert, pp. 122-127

- Allen, pp. 315-317

- Gilbert, p. 147

- Smith, (Vol. Two), p. 1393

- Smith, (Vol. Two), p. 1394

- Gilbert, p. 154

- Smith, (Vol. Two), p. 1399

- Smith, (Vol. Two), p. 1330

- Allen, pp. 330-331

- Allen, p. 331

- Allen, pp. 331-332

- Gilbert, pp. 177-178

- Allen, p. 332

- Allen, pp. 330-333

- Gilbert, pp. 190-205

- Maya Jasanoff, Liberty's Exiles: American Loyalists in the Revolutionary World (2011).

- Russell, David Lee (2000). The American Revolution in the Southern colonies. McFarland & Co. p. 317. ISBN 0-7864-0783-2.

- Fred Landon, Western Ontario and the American frontier (1941) p 280.

- Allen, Thomas B. (2011). Tories : fighting for the King in America's first civil war (1st Harper pbk ed.). Harper. p. 328. ISBN 978-0061241819.

- Allen, p. 175

- Allen, p. 333

- D.G.G. Kerr, ed., A Historical Atlas of Canada ( Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1966), pp. 36-37

- Keith A. Sandiford. Measuring the Moment: Strategies of Protest in Eighteenth-century Afro-English Writing (Susquehanna University Press, 1988), p 24.