Filasterea

Filasterea is a proposed basal Filozoan clade that includes Ministeria and Capsaspora.[1] It is a sister clade to the Choanozoa in which the Choanoflagellatea and Animals appeared. Originally proposed by Shalchian-Tabrizi et al. in 2008, based on a phylogenomic analysis with dozens of genes. Filasterea was found to be the sister-group to the clade composed of Metazoa and Choanoflagellata within the Opisthokonta, a finding that has been further corroborated with additional, more taxon-rich, phylogenetic analyses.[2][3][4]

| Filasterea | |

|---|---|

| |

| Capsaspora owczarzaki | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| Class: | Filasterea Salchian-Tabrizi, 2008 |

| Families and Genera | |

| |

Etymology

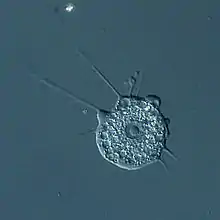

From Latin filum meaning "thread" and Greek aster meaning "star", it indicates the main morphological features shared by all their integrants: small, rounded amoeboids with a mononucleated cellular body, covered in long and radiating cell protrusions known as filopodia. These filopodia may be involved in substrate adhesion and capture of prey.

Applications

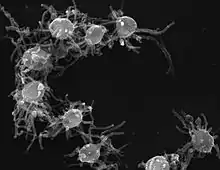

There are currently cultures from two filasterean species: Capsaspora owczarzaki and Ministeria vibrans, the first isolated from within a fresh-water snail, the second a marine, free-living bacteriovore. The complete genome sequence of C. owczarzaki has been obtained [5] and the genome sequence of M. vibrans is being sequenced. Comparative analyses have shown that Filasterea are key to unravel the genetic repertoire of the unicellular ancestor of animals and to provide insights into the origin of Metazoa. Metabarcoding analyses of 18S ribosomal RNA in marine environments have failed to recover other filasterean representatives,[6][7] suggesting this clade may not be especially abundant in natural ecosystems.

Taxonomy

- Class Filasterea Shalchian-Tabrizi et al. 2008[8][9][4]

- Order Ministeriida Cavalier-Smith 1997[10][11]

- Family Ministeriidae Cavalier-Smith 2008[1]

- Genus Ministeria Patterson et al. 1993

- Ministeria marisola Patterson et al. 1993

- Ministeria vibrans Tong 1997

- Genus Ministeria Patterson et al. 1993

- Family Capsasporidae Cavalier-Smith 2008[1]

- Genus Capsaspora Hertel et al. 2002

- Capsaspora owczarzaki Hertel et al. 2002

- Genus Pigoraptor Tikhonenkov et al. 2017[4]

- Genus Capsaspora Hertel et al. 2002

- Family Ministeriidae Cavalier-Smith 2008[1]

- Order Ministeriida Cavalier-Smith 1997[10][11]

| Opisthokonta |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In some research Capsaspora is found to be more closely related to Choanozoa than Ministeria.[12]

References

- Shalchian-Tabrizi K, Minge MA, Espelund M, et al. (7 May 2008). Aramayo R (ed.). "Multigene phylogeny of choanozoa and the origin of animals". PLOS ONE. 3 (5): e2098. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.2098S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002098. PMC 2346548. PMID 18461162.

- Torruella, Guifré; Derelle, Romain; Paps, Jordi; Lang, B. Franz; Roger, Andrew J.; Shalchian-Tabrizi, Kamran; Ruiz-Trillo, Iñaki (February 2012). "Phylogenetic relationships within the Opisthokonta based on phylogenomic analyses of conserved single-copy protein domains". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 29 (2): 531–544. doi:10.1093/molbev/msr185. ISSN 1537-1719. PMC 3350318. PMID 21771718.

- Torruella, Guifré; de Mendoza, Alex; Grau-Bové, Xavier; Antó, Meritxell; Chaplin, Mark A.; del Campo, Javier; Eme, Laura; Pérez-Cordón, Gregorio; Whipps, Christopher M. (2015-09-21). "Phylogenomics Reveals Convergent Evolution of Lifestyles in Close Relatives of Animals and Fungi". Current Biology. 25 (18): 2404–2410. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.07.053. ISSN 1879-0445. PMID 26365255.

- Hehenberger, Elisabeth; Tikhonenkov, Denis V.; Kolisko, Martin; Campo, Javier del; Esaulov, Anton S.; Mylnikov, Alexander P.; Keeling, Patrick J. (2017). "Novel Predators Reshape Holozoan Phylogeny and Reveal the Presence of a Two-Component Signaling System in the Ancestor of Animals". Current Biology. 27 (13): 2043–2050.e6. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.06.006. PMID 28648822.

- Suga, Hiroshi; Chen, Zehua; Mendoza, Alex de; Sebé-Pedrós, Arnau; Brown, Matthew W.; Kramer, Eric; Carr, Martin; Kerner, Pierre; Vervoort, Michel (2013-08-14). "The Capsaspora genome reveals a complex unicellular prehistory of animals". Nature Communications. 4: ncomms3325. Bibcode:2013NatCo...4.2325S. doi:10.1038/ncomms3325. PMC 3753549. PMID 23942320.

- del Campo, Javier; Ruiz-Trillo, Iñaki (2013-04-01). "Environmental Survey Meta-analysis Reveals Hidden Diversity among Unicellular Opisthokonts". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 30 (4): 802–805. doi:10.1093/molbev/mst006. ISSN 0737-4038. PMC 3603316. PMID 23329685.

- Del Campo, Javier; Mallo, Diego; Massana, Ramon; de Vargas, Colomban; Richards, Thomas A.; Ruiz-Trillo, Iñaki (September 2015). "Diversity and distribution of unicellular opisthokonts along the European coast analysed using high-throughput sequencing". Environmental Microbiology. 17 (9): 3195–3207. doi:10.1111/1462-2920.12759. ISSN 1462-2920. PMC 4500835. PMID 25556908.

- Adl; et al. (28 September 2012), "The Revised Classification of Eukaryotes" (PDF), Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology, 59 (5): 429–493, doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2012.00644.x, PMC 3483872, PMID 23020233, archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-16

- Silar, Philippe (2016), "Protistes Eucaryotes : Origine, Evolution et Biologie des Microbes Eucaryotes", HAL Archives-ouvertes: 1–462

- Ondřej Zicha (1999), "Ministeria", BioLib.cz, retrieved 2016-04-21

- Ruggiero; et al. (29 April 2015), "A Higher Level Classification of All Living Organisms", PLOS ONE, 10 (4): e0119248, Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1019248R, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0119248, PMC 4418965, PMID 25923521

- Reynolds, Nicole K.; Smith, Matthew E.; Tretter, Eric D.; Gause, Justin; Heeney, Dustin; Cafaro, Matías J.; Smith, James F.; Novak, Stephen J.; Bourland, William A. (2017). "Resolving relationships at the animal-fungal divergence: A molecular phylogenetic study of the protist trichomycetes (Ichthyosporea, Eccrinida)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 109: 447–464. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2017.02.007. ISSN 1055-7903. PMID 28219758.