Sound-on-film

Sound-on-film is a class of sound film processes where the sound accompanying a picture is recorded on photographic film, usually, but not always, the same strip of film carrying the picture. Sound-on-film processes can either record an analog sound track or digital sound track, and may record the signal either optically or magnetically. Earlier technologies were sound-on-disc, meaning the film's soundtrack would be on a separate phonograph record.[1]

History

Sound on film can be dated back to the early 1880s, when Charles E. Fritts filed a patent claiming the idea. In 1923 a patent was filed by E. E. Ries, for a variable density soundtrack recording, which was submitted to the SMPE (now SMPTE), which used the mercury vapor lamp as a modulating device to create a variable-density soundtrack. Later, Case Laboratories and Lee De Forest attempted to commercialize this process, when they developed an Aeolite glow lamp, which was deployed at Movietone Newsreel at the Roxy Theatre in 1927. In 1928, Fox Film purchased Case Laboratories and produced its first talking film In Old Arizona using the Aeolite system. The variable-density sound system was popular until the mid-1940s.[2]

Opposite with variable-density, in the early 1920s, variable-area sound recording was first experimented on by the General Electric Company, and later was applied by RCA which refined GE's technology. After the mid-1940s, variable-area system superseded the variable-density system, and became the major analog sound-on-film system until modern day.

Analog sound-on-film recording

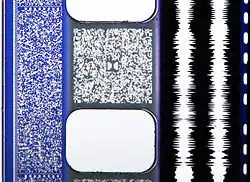

The most prevalent current method of recording analogue sound on a film print is by stereo variable-area (SVA) recording, a technique first used in the mid-1970s as Dolby Stereo. A two-channel audio signal is recorded as a pair of lines running parallel with the film's direction of travel through the projector's screen. The lines change area (grow broader or narrower) depending on the magnitude of the signal. The projector shines light from a small lamp, called an exciter, through a perpendicular slit onto the film. The image on the small slice of exposed track modulates the intensity of the light, which is collected by a photosensitive element: a photocell, a photodiode or CCD.

In the early years of the 21st century distributors changed to using cyan dye optical soundtracks on color stocks instead of applicated tracks, which use environmentally unfriendly chemicals to retain a silver (black-and-white) soundtrack. Because traditional incandescent exciter lamps produce copious amounts of infra-red light, and cyan tracks do not absorb infra-red light, this change required theaters to replace the incandescent exciter lamp with a complementary colored red LED or laser. These LED or laser exciters are backwards-compatible with older tracks.

Earlier processes, used on 70 mm film prints and special presentations of 35 mm film prints, recorded sound magnetically on ferric oxide tracks bonded to the film print, outside the sprocket holes. 16 mm and Super 8 formats sometimes used a similar magnetic track on the camera film, bonded to one side of the film on which the sprocket holes had not been punched ("single perforated") for the purpose. Film of this form is no longer manufactured, but single-perforated film without the magnetic track (allowing an optical sound track) or, in the case of 16 mm, utilising the soundtrack area for a wider picture (Super 16 format) is readily available.

Digital sound-on-film formats

Three different digital soundtrack systems for 35 mm cinema release prints were introduced during the 1990s. They are: Dolby Digital, which is stored between the perforations on the sound side; SDDS, stored in two redundant strips along the outside edges (beyond the perforations); and DTS, in which sound data is stored on separate compact discs synchronized by a timecode track on the film just to the right of the analog soundtrack and left of the frame[3] (sound-on-disc). Because these soundtrack systems appear on different parts of the print, one movie can contain all of them, allowing broad distribution without regard for the sound system installed at individual theatres.

Sound-on-film formats

Almost all sound formats used with motion-picture film have been sound-on-film formats, including:

Optical analog formats

- Fox/Western Electric (Westrex) Movietone, are variable-density formats of sound film. (No longer used, but still playable on modern 35 mm projectors.)

- Tri-Ergon, another variable-density format prevalent in Germany and Europe until the 1940s. The US patent rights of this Berlin based company were bought by William Fox in 1926, leading to a patent war with the US film industry lasting until 1935. Tri-Ergon amalgamated with a number of other German competitors from 1928 to form the Dutch-controlled Tobis Film syndicate in 1930,[4][5] licensing the system to UFA GmbH[6] as UFA-Klang.

- RCA Photophone, a variable-area format since the late 1920s—now universally used for optical analog soundtracks. Since the late 1970s usually with a Dolby encoding matrix.

Encoding matrices

- Dolby Stereo (SVA)

- Dolby SR

- Ultra Stereo

Optical digital formats

Obsolete formats

- Cinema Digital Sound, an optical format which was the first commercial digital sound format, used between 1990 and 1992

- Fantasound. This was a system developed by RCA and Disney Studios with a multi-channel soundtrack recorded on a separate strip of film from the picture. It was used for the initial release of Walt Disney's Fantasia (1940)

- Phonofilm, patented by Lee De Forest in 1919, defunct by 1929

See also

References

- Encyclopedia of Recorded Sound

- Fayne, John G. "(History of) Motion Picture Sound Recording" (PDF). The Journal of Audio Engineering Society. Retrieved January 26, 2022.

- DTS | Corporate | Milestones Archived 2010-06-09 at the Wayback Machine

- "KLANGFILM - Early Systems (1928 - 1931)", Komagane, Nagano Prefecture : Caliber Code Corporation. Last accessed 5 September 2020.

- Gomery, Douglas (1976). "Tri-Ergon, Tobis-Klangfilm, and the Coming of Sound". Cinema Journal. 16 (1): 51–61. doi:10.2307/1225449. JSTOR 1225449. Retrieved September 6, 2020 – via JSTOR.

- Kreimeier, K. (translation: Hill and Wang). 1999. THE UFA STORY. London: University of California Press.