Finger-four

The finger-four formation (also known as the "four finger formation" and the "Fingertip Formation") is a flight formation used by fighter aircraft. It consists of four aircraft, and four of these formations can be combined into a squadron formation.

Description

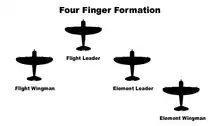

The formation consists of a flight of four aircraft, consisting of a "lead element" and a "second element", each of two aircraft. When viewing the formation from above, the positions of the planes resemble the tips of the four fingers of a human right hand (without the thumb), giving the formation its name.

The lead element is made up of the flight leader at the very front of the formation and one wingman to his rear left. The second element is made up of an additional two planes, the element leader and his wingman. The element leader is to the right and rear of the flight leader, followed by the element wingman to his right and rear.

Both the flight leader and element leader have offensive roles, in that they are the ones to open fire on enemy aircraft while the flight remains intact. Their wingmen have a defensive role — the flight wingman covers the rear of the second element and the element wingman covers the rear of the lead element.

Four of these flights can be assembled to form a squadron formation which consists of two staggered lines of fighters, one in front of the other. Each flight is usually designated by a color (i.e. Red, Blue, Yellow, and Green).

One disadvantage of the finger-four formation was that it left the least-experienced flier, the number two wingman, in the most exposed position (as "tail-end Charlie"). These were particularly vulnerable to a surprise diving attack, and in some cases could be picked off without the others in the formation even noticing.

History

The formation was developed by several air forces independently in the 1930s. The Finnish Air Force adopted it in 1934 and 1935.[1][2] Luftwaffe pilots developed the formation independently in 1938 during the Spanish Civil War, and were the first to use it in combat.

Finnish experiment

During the 1930s, the Finnish Air Force, aware of its weakness in numbers compared to its neighbours, sought to offset the disadvantage by a radical rethink of its tactics. The new tactical philosophy emphasized aggression, a willingness to attack regardless of the odds, as well as shooting accuracy at a time when aerobatic skill was prized by most air forces. Hand in hand with the changes was the adoption of the pair and finger-four formation, which allowed economy and gave the flexibility that the new tactics required. The aircraft in the new formations had greater vertical and horizontal separation and so they were free to scan in all directions for enemy aircraft, rather than focusing on maintaining a close formation. That allowed the pilots to maintain greater situational awareness and reduced their chance of being spotted by the enemy. The two pairs could split and attack on their own. The pilot who spotted the enemy would become the leader of the pair or even the whole flight for the duration of the attack, as he had the best situational awareness at that moment.

With no guarantee of success, the FAF adopted the new tactics and was later to find the validity of this approach during the Winter War (1939–1940) with the Soviet Union. The Finnish Air Force proved their effectiveness by achieving a 16:1 kill ratio with the finger-four against the Soviet Air Force, which used the conventional Vic formation.[2]

German experience in Spain

Involvement in the Spanish Civil War gave the fledgling Luftwaffe an early experience of combat conditions, but the "Condor Legion" quickly found its main fighter aircraft, the He 51, was outclassed by the Soviet I-16 in service with the Republicans. The new Bf 109B was effective but in short supply. For some time, only six were available, making the 3-plane Kette impractical. Flying in pairs (Rotte) or a two-pair Schwarm and using a more open formation (made possible by radio communication between aircraft) was found to confer other benefits.

Most notable in its development and use in the Luftwaffe were Günther Lützow and Werner Mölders and their fellow airmen. In the Luftwaffe, the flight (German: Schwarm) was made up of two pairs (German: Rotte) of aircraft. Each Rotte was composed of a leader and a wingman. The Rottenführer (pair leader) would attack enemy aircraft, leave his wingman to scan for threats and protect him while he engaged the enemy. The Germans thus eschewed the Finnish Air Force's more flexible approach.

The Luftwaffe continued the use of the formation during its Battle of France, the Battle of Britain and the invasion of the Soviet Union in which its effectiveness was shown to be considerably greater than the standard three-aircraft "Vic" close formation used by its opponents.[3] Later, the RAF, the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) and Soviet Air Forces adapted their tactics.

Other operators

The Soviet Air Force units in the Spanish Civil War soon adopted the formation flying against the Germans and in 1938 recommended its use when they returned home. However, most of the Spanish veterans were swept away during Stalin's Great Purge of the armed forces,[3] and the more conservative "Vic" remained the standard Soviet formation. The pary and zveno were not reintroduced until the after Operation Barbarossa forced reforms by Alexander Novikov in 1942 and 1943.[4]

The RAF similarly could not radically reform their fighter tactics until the end of the Battle of Britain. The easing of the pressure and a switch to a more offensive stance led to various experiments with formations. The flying ace Douglas Bader was the first RAF pilot to try the formation, in May 1941. After some refining it became the standard formation of his Duxford Wing and eventually spread throughout RAF.[5][6]

The United States Army Air Corps and Naval Aviation began using a concept called "Fighting Pair" from 1940 to 1941. Japan also adopted the finger-four formation during World War II.[7][8][9]

Missing man formation

The finger-four formation became less common after World War II. However, it is still used in the "Missing Man Formation" at pilots' funeral ceremonies. The formation performs a fly-by in level flight over the funeral, at which point the second element leader climbs vertically and departs the formation, symbolizing the departure of the person being honored.

See also

Footnotes

- FAF history at sci.fi. Archived 2012-03-01 at the Wayback Machine

- Finnish Air Force in World War II, Heikki Nikunen Archived 2016-08-07 at the Wayback Machine at century-of-flight.

- Spick p27

- Hardesty p. 84

- Burns pp. 150–53

- Bader, Douglas (1973) p. 132-133

- Bickers (1996) p. 150

- Boyne (2003) p. 192

- Buell, Griess, Bradley & Dice (2002) p. 77

References

- Bader, Douglas Stewart (1973). Fight for the Sky: The Story of the Spitfire and the Hurricane. Sidwik and Jackson Ltd. p. 132-133. ISBN 0-283-97984-4.

- Bickers, Richard Townshend (1996). Von Richthofen: the legend evaluated. Naval Institute Press. p. 892. ISBN 1-55750-571-3.

- Boyne, Walter J. (2003). The influence of air power upon history. Pelican Publishing Company. p. 447. ISBN 1-58980-034-6.

- Buell, Thomas; Griess, Thomas E.; Bradley, John H.; Dice, Jack W. (2002). The Second World War: Europe and the Mediterranean. Square One Publishers. p. 448. ISBN 0-7570-0160-2.

- Burns, Michael (1990 reprint 1998) Bader: the man and his men Cassell ISBN 0-304-35052-4

- Gray, Stephen Roberts (2007). Rampant Raider: an A-4 Skyhawk pilot in Vietnam. Naval Institute Press. p. 284. ISBN 978-1-59114-342-0.

- Hardesty, Von (1982) Red Phoenix: the rise of Soviet air power 1941-1945 Arms and Armour Press ISBN 0-85368-565-7

- Holmes, Tony (2007). Spitfire VS Bf 109: Battle of Britain. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84603-190-7

- Spick, Mike (1996) Luftwaffe Fighter Aces Greenhill Books ISBN 1-85367-560-1

- Johnson J.E. (1964) Full Circle Cassell Military Paperbacks ISBN 0-304-35860-6

Further reading

- Air power history: turning points from Kitty Hawk to Kosovo

- Fire in the Sky: The Air War in the South Pacific

- Officers in Flight Suits: The Story of American Air Force Fighter Pilots in the Korean War

- Eagles of the Third Reich - Men of Luftwaffe

- The Luftwaffe Over Germany: Defense of the Reich By Donald Caldwell, Richard Muller