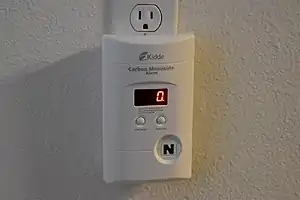

Carbon monoxide detector

A carbon monoxide detector or CO detector is a device that detects the presence of the carbon monoxide (CO) gas to prevent carbon monoxide poisoning. In the late 1990s Underwriters Laboratories changed the definition of a single station CO detector with a sound device to carbon monoxide (CO) alarm. This applies to all CO safety alarms that meet UL 2034 standard;[1] however for passive indicators and system devices that meet UL 2075, UL refers to these as carbon monoxide detectors. Most CO detectors use a sensor with a defined, limited lifespan, and will not work indefinitely.

CO is a colorless, tasteless and odorless gas produced by incomplete combustion of carbon-containing materials. It is often referred to as the "silent killer" because it is virtually undetectable by humans. In a study by Underwriters Laboratories, "Sixty percent of Americans could not identify any potential signs of a CO leak in the home".[2] Elevated levels of CO can be dangerous to humans depending on the amount present and length of exposure. Smaller concentrations can be harmful over longer periods of time while increasing concentrations require diminishing exposure times to be harmful.[3]

CO detectors are designed to measure CO levels over time and sound an alarm before dangerous levels of CO accumulate in an environment, giving people adequate warning to safely ventilate the area or evacuate. Some system-connected detectors also alert a monitoring service that can dispatch emergency services if necessary.

While CO detectors do not serve as smoke detectors and vice versa, combined smoke/CO detectors are also sold.[4] In the home, some common sources of CO include open flames, space heaters, water heaters, blocked chimneys or running a car or grill inside a garage.[5]

Installation

The devices can either be battery-operated or AC powered (with or without a battery backup). Battery-powered devices advertise a battery lifetime of up to 10 years. The gas sensors in CO alarms have a limited life span, typically two to five years.[6] Newer models are designed to signal a need to be replaced after a set time span. CO detectors all have "test" buttons like smoke detectors, but the test buttons only test the battery, electronic circuit and buzzer, not the alarm’s ability to sense gas.

According to the carbon monoxide guidelines of the National Fire Protection Association, CO detectors should be installed in each sleeping area in a dwelling, and each detector should be located "on the wall, ceiling or other location as specified in the installation instructions that accompany the unit".[7]

CO detectors are available as stand-alone models, or system-connected devices which can be monitored remotely.[8]

Function

The primary purpose of CO detectors is to sound an alarm to warn occupants of an enclosed space of a dangerous level of carbon monoxide. The alarm should normally sound after 40 to 165 minutes if the concentration rises to 100ppm, and in 4 to 15 minutes at 400ppm. The alarm should not sound too quickly, as brief false alarms may prompt users to disable the alarm, leaving them unprotected.[9] Alarm devices may display the CO level. There are also measuring instruments designed to display CO concentrations down to low, non-dangerous levels, rather than detect and warn of dangerous levels.

Some detectors without UL certification have been found not to sound at the specified threshold, or to sound within seconds.[9]

Wireless home safety devices are available that link carbon monoxide detectors to vibrating pillow pads, strobes or a remote warning handset.

Sensors

Early designs used a chemical detector consisting of a white pad that faded to a brownish or blackish color in the presence of carbon monoxide. Such detectors are cheap, but only give a visual warning. As carbon monoxide related deaths increased during the 1990s, audible alarms became standard.

The alarm points on carbon monoxide detectors are not a simple alarm level (as in smoke detectors) but are a concentration-time function. At lower concentrations, e.g. 100 parts per million (PPM), the detector does not sound an alarm for many tens of minutes. At 400 PPM, the alarm sounds within a few minutes. This concentration-time function is intended to mimic the uptake of carbon monoxide in the body while also preventing false alarms due to brief bursts of carbon monoxide from relatively common sources such as cigarette smoke.

Four types of sensors are available, varying in cost, accuracy and speed of response.[10] Most detectors do not have replaceable sensors.

Opto-chemical type

The detector consists of a pad of a coloured chemical which changes colour upon reaction with carbon monoxide. They only provide a qualitative warning of the gas however. The main advantage of these detectors is that they are the lowest cost, but the downside is that they also offer the lowest level of protection.

One reaction used for carbon monoxide detection is potassium disulfitopalladate (II) catalytic oxidation:

As reaction progresses, atomic palladium release causes the color to change from yellow to brown to black.

Biomimetic type

A biomimetic sensor works in a fashion similar to hemoglobin which darkens in the presence of CO proportional to the amount of carbon monoxide in the surrounding environment. It uses cyclodextrins, a chromophore, and a number of metal salts. This can either be seen directly or connected to an infrared source of photons such as an IR LED and then monitored using a photodiode. Battery lifespan is usually two to three years with conventional alkaline, but a lithium battery will last the life of the product. The biotechnology based sensors have a useful operational life of six years. These products were the first to enter the mass market, but because they cost more than other sensors they are mostly used in higher-end areas and RVs. The technology has been improved and is the most reliable technology, according to a report from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.[11]

Electrochemical type

The electrochemical detector uses the principle of a fuel cell to generate an electrical current when the gas to be detected undergoes a chemical reaction. The generated current is precisely related to the amount of carbon monoxide in the immediate environment close to the sensor. Essentially, the electrochemical cell consists of a container, two electrodes, connection wires and an electrolyte, typically sulfuric acid. Carbon monoxide is oxidized at one electrode to carbon dioxide while oxygen is consumed at the other electrode. For carbon monoxide detection, the electrochemical cell has advantages over other technologies in that it has a highly accurate and linear output to carbon monoxide concentration, requires minimal power as it is operated at room temperature, and has a long lifetime, which typically is five years to ten years. This technology has become the dominant technology in the United States and in Europe. Test buttons only indicate the operational effectiveness of the battery, circuit and buzzer. The only way to fully test the operation of a CO alarm using an electrochemical cell is with a known source of calibrated test gas delivered in a shroud to maintain the concentration level for the test period.

Semiconductor type

Thin wires of the semiconductor tin dioxide on an insulating ceramic base provide a sensor monitored by an integrated circuit. This sensing element must be heated to approximately 400 °C for operation. Oxygen increases resistance of the tin dioxide while carbon monoxide reduces it. The integrated circuit monitors the resistance of the sensing element. Lifespans are approximately five years and alarms need testing on installation and at least annually with a test gas.

Due to the large power demand of this sensor it is usually powered from the mains. A battery-powered, pulsed sensor is available with a lifetime of months.

This technology is widely used in Japan and elsewhere in the Far East, with some market penetration in USA. However the superior performance of electrochemical cell technology is beginning to displace this technology.

Concentration readout

Although all home detectors use an audible alarm signal as the primary indicator, some versions also offer a digital readout of the CO concentration, in parts per million (ppm). Typically, they can display both the current reading and a peak reading from memory of the highest level measured over a period of time. These advanced models cost somewhat more but are otherwise similar to the basic models.

The models with display have the advantages of indicating levels below the alarm threshold, reporting levels that may have occurred during an absence, and assessing the degree of hazard if the alarm sounds. They may also aid emergency responders in evaluating the level of past or ongoing exposure or danger.

Portable

Portable detectors are designed for aircraft, cars and trucks, and warn vehicle occupants of any CO hazard.

CO measurement instruments

Portable meters which display CO concentration down to a few ppm, more sensitive than home safety CO detectors and correspondingly much more expensive, are used by industrial hygienists and first responders, and for maintenance and tracing a CO leak. These devices measure low levels of CO in seconds, rather than the minutes or hours of residential alarms. Like other test equipment, professional CO meters must be tested and recalibrated periodically.

Legislation

United States

In the US (As of January 2017) 32 states have enacted statutes regarding carbon monoxide detectors, and another 11 have promulgated regulations on CO detectors,[12] as well as in Washington DC and New York City. In Canada, CO alarm requirements came into force on October 15, 2014 in Ontario,[13] there is a strong movement in Alberta to make CO detectors mandatory in all homes.[14]

More and more states are legislating for their installation as a mandatory feature.[15]

House builders in Colorado are required to install carbon monoxide detectors in new homes in a bill signed into law in March 2009 by the state legislature. House Bill 1091 requires installation of the detectors in new and resold homes near bedrooms as well as rented apartments and homes. It took effect on July 1, 2009. The legislation was introduced after the death of Denver investment banker Parker Lofgren and his family. Lofgren, along with his wife and children were found dead in their home near Aspen, Colorado on Nov. 27, 2008, victims of carbon-monoxide poisoning.

In New York State, "Amanda's Law" (A6093A/C.367) requires one- and two-family residences which have fuel burning appliances to have at least one carbon monoxide alarm installed on the lowest story having a sleeping area, effective since February 22, 2010. Although homes built before Jan. 1, 2008 are allowed to have battery-powered alarms, homes built after that date need to have hard-wired alarms. In addition, New York State contractors have to install a carbon monoxide detector when replacing a fuel burning water heater or furnace if the home is without an alarm. The law is named for Amanda Hansen, a teenager who died from carbon monoxide poisoning from a defective boiler while at a sleepover at a friend's house.[16][17]

Alaska House Bill 351 requires a carbon monoxide detector be installed in dwelling units that contain or are serviced by a carbon based fuel appliance or other device that produces by products of combustion.

In July 2011, California required installation of carbon monoxide detectors in existing single-family homes, with multifamily homes following in 2013.[18] CA Law 2015 require all new installation of smoke and CO alarms to be 10 year non serviceable type.[19] Existing alarms may not need to be replaced for home owners, see local codes. Required alarm location also vary per local enforcing agencies. In Maine, all rental units must have carbon monoxide detectors although in non rental homes they are recommended but are not required. [20]

Standards

- North America

The Canadian Mortgage and Housing Association reports, "The standards organizations of Canada (CSA) and the United States (Underwriters Laboratories or UL) have coordinated the writing of CO standards and product testing. The standards as of 2010 prohibit showing CO levels of less than 30 ppm on digital displays. The most recent standards also require the alarm to sound at higher levels of CO than with previous editions of the standard. The reasoning behind these changes is to reduce calls to fire stations, utilities and emergency response teams when the levels of CO are not life threatening. This change will also reduce the number of calls to these agencies due to detector inaccuracy or the presence of other gases. Consequently, new alarms will not sound at CO concentrations up to 70 ppm. Note that these concentrations are significantly in excess of the Canadian health guidelines,"[21] (and also in excess of US Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Permissible exposure limits, which is 50 ppm).[22]

- UK

In the UK a domestic/Type-B alarm compliant with BS EN 50291:2001 should emit an audible alarm after about 3 minutes exposure to 300 ppm CO, or 10 to 40 minutes at 100 ppm, or 60 to 90 minutes at 50 ppm.

References

- "Standard for Single and Multiple Station Carbon Monoxide Alarms". UL. Retrieved October 22, 2017.

- "UL Mobile | News". Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved February 28, 2016.

- NFPA 720: Standard for the Installation of Household Carbon Monoxide (CO) Warning Equipment, 2005 Edition, Annex B Dangers of Carbon Monoxide, B.1 Carbon Monoxide, Table B.1 Symptoms of Carbon Monoxide Exposure Based on Concentration

- "Carbon Monoxide Detectors Buying Guide". ranky10.com. September 22, 2017. Retrieved October 22, 2017.

- U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission, Carbon Monoxide Detectors Can Save Lives (CPSC Document #5010), archived from the original on April 9, 2009, retrieved July 29, 2007

- Sorenson, Ida (April 16, 2022). "9 Reasons Why Your Carbon Monoxide Detector Went Off Then Stopped". Retrieved October 14, 2022.

- NFPA 720: Standard for the Installation of Household Carbon Monoxide (CO) Warning Equipment, 2005 Edition

- "Top 5 Things to Know About CO," LifeSafety magazine, Fall 2006

- Hope, Paul (March 14, 2017). "3 Carbon Monoxide Alarms Named 'Don't Buy: Safety Risk' by Consumer Reports". Consumer Reports.

- Guide to Prevent Carbon Monoxide Poisoning, retrieved July 29, 2007

- Gundel, Lara A.; Michael G. Apte; Albert R. Nematollahi (1998). Carbon Monoxide Detector Technology Comparison: Response to Various Gases (PDF) (Technical report). Ernest Orlando Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. LBNL-40556. Retrieved January 14, 2014.

- "Carbon Monoxide Detector Requirements, Laws and Regulations". National Conference of State Legislatures. April 3, 2017. Retrieved October 22, 2017.

- "Carbon Monoxide Alarm Questions and Answers". Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services. Archived from the original on October 23, 2017. Retrieved October 22, 2017.

- Eva Ferguson (January 6, 2017). "Carbon monoxide safety advocate to lobby Alberta to make detectors mandatory in Alberta". Calgary Sun. Archived from the original on October 24, 2017. Retrieved October 22, 2017.

- http://artclesgalore.com/article.php?id=2879%5B%5D

- "Carbon Monoxide Virtual Toolbox". Division of Homeland Security and Emergency Services. November 7, 2014.

- "Welcome Page". New York State Office of Fire Prevention & Control. Archived from the original on May 21, 2010.

- Senate Bill 183

- Updated Smoke Alarm Requirement (Report). February 12, 2015. California State Fire Marshal Information Bulletin 14-006. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 6, 2016.

- Carbon Monoxide Environmental & Occupational Health Programs.

- Canadian Mortgage and Housing Association Archived April 11, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- "Carbon monoxide". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). April 11, 2016. Retrieved May 10, 2016.

External links

- Mike Busch (November 9, 2003). "Carbon Monoxide Detectors". Avweb.com. Archived from the original on February 11, 2004. Retrieved October 18, 2017.

- "Carbon Monoxide Alarm Considerations for Code Authorities" (PDF). UL. 2014 [First published 2009]. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 17, 2017. Retrieved October 18, 2017.

.jpg.webp)