Franco-Moroccan War

The Franco-Moroccan War (Arabic: الحرب الفرنسية المغربية, French: Guerre franco-marocaine) was fought between the Kingdom of France and the Sultanate of Morocco from 6 August to 10 September 1844. The principal cause of war was the retreat of Algerian resistance leader Abd al-Kader into Morocco following French victories over many of his tribal supporters during the French conquest of Algeria and the refusal of the Sultan of Morocco Moulay Abd al-Rahman to abandon the cause of Abd al-Kader against colonial occupation.[1][2]

| Franco-Moroccan War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

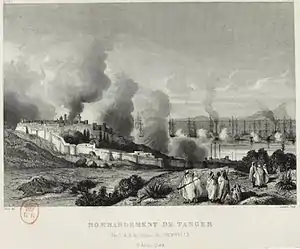

Painting of the Bombardment of Tangier. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

15,000 troops 15 warships |

40,000 cavalry 300 artillery | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

41+ killed 163 wounded |

1,150 killed 28 cannons lost | ||||||||

Background

Shortly after Algiers fell in 1830, and fearing French invaders, Muhammad Bennouna organised a deputation to ask Moulay Abd al-Rahman to accept a bay'a from Tlemcen. The people of Tlemcen offered Abd al-Rahman the oath of allegiance that would legally establish 'Alawi rule over their region.[3][4] The Sultan consulted the 'ulama of Fez, who ruled that the inhabitants of Tlemcen had already sworn allegiance to the Ottoman Sultan and they could not change it now.[3] In the summer of 1830 Sultan Abd al-Rahman accepted boatloads of Algerian refugees arriving in the ports of Tangier and Tétouan, ordering his governors to find them housing and settle them into new work.[4] In September 1830 the Tlemcenis sent another letter arguing that the authority of the Sublime Porte no longer existed, and that its former representatives had been irreligious tyrants. The notables of the beleaguered city kept pressuring for a Moroccan intervention, reminding Abd al-Rahman that the defense of Islam was the duty of the just ruler.[3][4]

In October 1830 the sultan named his nephew Moulay Ali ben Slimane, who was only fifteen years old, as Khalifa of Tlemcen and sent him to take control of Tlemcen. An uncle of the sultan, Idris al-Jarari, the Governor of Oujda, was sent with him to help in protecting the city.[5][2] The Moroccan troops were warmly welcomed, even in the provinces of Titteri and Constantine.[6] The Moroccan Sultan's authority was speedily recognised in all parts of the regency. The khotba, or public prayer, was pronounced in all the mosques for the Sultan of Morocco. Everything conspired to confirm the belief that Algeria had peaceably passed under the Moorish sceptre.[7]

Moulay Ali let local rivalries continue unchecked, while his troops pillaged pillaged the countryside instead of taking the citadel of Tlemcen, still manned by Ottoman troops. In March 1831 the sultan recalled both of them and nominated the Governor of Tétouan Ibn al-Hami in their place.[5][2] The Moroccan intervention in Algeria made it clear that the 'Alawi leadership could not orchestrate the popular feelings against the French to their own advantage. In January 1832 France sent an ambassador to Sultan Abd al-Rahman, demanding that he withdraw Morocco’s presence from Tlemcen. The Sultan initially refused to evacuate the city, but when a French warship appeared at Tangier the Makhzen negotiated and the sultan agreed to withdraw his troops. The Moroccan troops evacuated Tlemcen in May. But before Ibn al-Hami left, he appointed a new governor in the sultan's name. This was the local head of the Qadiriyya tariqa, Muhyi al-Din, who began to organise resistance to the French. In November he handed the leadership to his son, Abd al-Kader.[8][2] Another embassy was sent by the Marabouts and chiefs to Fez to implore the Moroccan Sultan to provide aid and assistance. Abd al-Rahman complied with their request, by sending a confidential agent to Mascara. This proceeding, however, produced no effect.[6]

Prelude

When the French expanded their foothold into the interior, Abd al-Kader arose as the leader of the resistance. Abd al-Kader was careful, however, not to appear to challenge Abd al-Rahman's own claims of suzerainty, and made it known that he was acting merely as the Moroccan sultan's Khalifa, or deputy.[9] The Emir Abd al-Kader continued to cultivate his standing among his followers by pursuing the holy war. He called on Moroccan tribesmen of the eastern Rif Mountains to join his resistance, and he entreated the sultan to help him with military supplies. Abd al-Rahman complied by maintaining a steady stream of horses, arms, and money flowing to him.[10] Several of the frontier Morocco tribes had long been in open revolt against their sovereign. Abd al-Kader marched against them, subdued them, and sent the leaders of the rebellion in chains to Oujda, forwarding at the same time a letter from himself to Sultan Abd al-Rahman, stating his services. This was to conciliate the authorities of an empire where he was afterwards to seek assistance.[11][12]

In October 1842, after another defeat, Abd al-Kader fled with his followers from the territory of their fathers to Morocco.[13] Abd al-Kader had for some time made the Morocco frontier the basis of his forays into Algeria. He could retire within the Moroccan territory without molestation. The French, in order not to be thus baffled, had at last advanced a strong division to that part of the frontier from whence he made his sallies. Generals Louis Juchault de Lamoricière and Marie Alphonse Bedeau fixed on their encampment on Lalla Maghnia. On the 22nd of May, 1844, El-Gennaoui, commander of the Moorish garrison at Oujda, summoned the French to evacuate Lalla Maghnia. On the 30th, the Moorish Qaid, unable to control the fanatic passions of the contingents assembled around him, gave way to fire into the French entrenchments. Lamoricière and Bedeau quickly defeated and dispered them, with the Moorish troops falling back upon Oujda.[14][15] On the 15th of June, the Moorish troops approached unnoticed, and fired upon the French troops, wounding Captain Eugène Daumas and two men. The Moorish chief declared that the frontier must be set back to the Tafna River, and in case of refusal it was war.[15] The Governor-General of Algeria and French Marshal Thomas Robert Bugeaud wrote to El-Gennaoui insisting that the border be demarcated along the Kiss River, a position further west than the Tafna River, and threatening of war if Morocco would continue receiving and succouring Abd al-Kader.[16] The Marshal was seconded by one of King Louis Philippe I's sons, the young Admiral François d'Orléans, Prince of Joinville, who was commanding the cruisers off the Moorish coasts.[17]

On the 19th of June, violating the frontier, Marshal Bugeaud occupied Oujda.[18] The dispute, thus commenced on the frontier, soon spread into the higher regions of diplomacy. The French Government sent a squadron under Prince de Joinville to the coast of Morocco to support its official reclamations. Marshal Bugeaud received instructions to commence offensive operations by land.[19] The Emperor Abd al-Rahman sent orders to all his provincial Governors for a general levy. Abd al-Kader made his way into Djebel Amour, and endeavoured to raise the southern tribes against the French. They all remained faithful; the Emir only obtained a promise that they would join the Moorish army when it met the infidel forces.[18]

On the 1st of July, the Moors made an attack on the banks of Isly but fled at the first musket-shots. The French troops ascended the river on the 11th, and on the 13th killed some hundred horsemen of the Moorish tribes, losing only two men and five horses. On the 19th the French troops returned to Lalla Maghnia for refreshment.[18] The Prince de Joinville, cruising in the waters of Cádiz with a flying squadron, received orders to proceed to Tangier. The French Consul in Spain forwarded to the court of Fez Marshal Bugeaud's ultimatum to the Qaid Si el-Gennaoui.[20]

War

Bombardment of Tangier

The war began on August 6, 1844, at eight in the morning, when a French fleet under the command of the Prince of Joinville François d'Orléans, in his first action as a squadron commander, conducted a naval Bombardment of Tangier. In an hour's time all the outer batteries were destroyed; two works held out longer, the battery of the Kasbah and that of the marine fort. At eleven the fire ceased, the Prince commanding the squadron had executed the order of the Ministry, the exterior fortifications were in ruins, the town had been respected. The squadron, then, went into the Atlantic, passed along the coast of Morocco, and, though the weather was very bad, anchored before Mogador on the 11th of August. The condition of the sea would not allow of the vessels at once taking up their fighting positions. For three days they had to lie at anchor without being able to communicate.[21]

Battle of Isly

%252C_p_-_P2008_-_Mus%C3%A9e_Carnavalet.jpg.webp)

The Emperor Abd al-Rahman's son and heir presumptive, Sidi Mohammed, advanced towards Algeria, contrary to the orders of his father, with the intention of turning the French out of Lalla Maghnia. He was deceived by the reports of fanatic personages around him, and perhaps influenced by Abd al-Kader's agents, Sidi Mohammed even talked of a plan of conquering the province of Oran. Moulay Mohammed found the number of his soldiers increasing every day. All the Berber and Arab tribes that inhabit the vast territory extending from Fez to Oujda came to take part in the war against the infidels, and many Algerian tribes prayed for the success of the holy enterprise.[22] The conflict peaked on August 14, 1844 at the Battle of Isly, which took place near Oujda.[2] A large Moroccan force led by the Sultan's son Sidi Mohammed, was defeated by a smaller French royal force under the Governor-General of Algeria Thomas Robert Bugeaud.[23] As a consequence of the battle, Sidi Mohammed retreated to Taza and the Marshal spread his emissaries that he would pursue him there. Abd al-Rahman sent orders to his son to stay the Marshal's march, by making proposals of peace to him.[24] For his victory, King Louis Philippe I conferred the title of Duke of Isly upon Marshal Bugeaud. [25]

Bombardment of Mogador

The weather cleared up on the 15th. Mogador (Essaouira), Morocco's main Atlantic trade port, was attacked in the Bombardment of Mogador and briefly occupied by Joinville on August 16, 1844.[26][27] The Suffren, the Jemmapes, and the Triton, opened fire upon the fortifications. The Belle Poule and the other vessels of lighter draught entered the harbour and engaged the batteries of the Marina and those of the island defending the port. At first the Moors made a vigorous reply, but gradually slackened and then ceased their fire, being crushed by the projectiles from the squadron. The batteries fell into ruins, the guns were dismounted, and the gunners driven off. The island alone held out, being defended by a detachment of three hundred and twenty men. The steam-vessels Pluton, Gassendi and Phare, landed five hundred marines, who carried the position under a sharp fire and drive the defenders out of their last entrenchments. Next day a landing party completed the destruction of the works spared by shot. All the guns not dismounted were spiked, the powder drowned, and all the goods found in the custom-house burnt or thrown into the sea.[28]

While steamships played an important part in the operations at Tangier and Mogador, Joinville commanded both bombardments from the ship of the line Suffren, and the three ships of the line in his force provided most of the firepower.[1] The French lost no ships in the shelling, which Joinville called “much more of a political act than an act of warfare”, but suffered a significant casualty afterward, when the paddle steamer Groenland ran aground near Larache on the 26th of August and could not be saved.[1] The French Government gave a pledge to the United Kingdom that Tangier, as a quasi-European town, would be spared from hostilities.[29] The British had warships on hand at both Tangier and Mogador, and protested the bombardments. The Moroccan campaign, combined with concurrent Anglo-French tensions over Tahiti, fuelled a mild war scare.[1]

Aftermath

Treaty of Tangier

The war formally ended on September 10, 1844 with the signing of the Treaty of Tangier, in which Morocco agreed to recognize Algeria as part of the French Empire, reduce the size of its garrison at Oujda, and establish a commission to demarcate the border.[2] The peace treaty imposed on the Moroccan monarchy to abandon its support of Abd al-Kader and brand him an “outlaw”.[30][31] The 4th article of the treaty of peace stipulated that “Hajj Abd al-Kader is placed beyond the pale of the law throughout the entire extent of the Empire of Morocco, as well as in Algeria. He will, consequently, be pursued by main force, by the French on the territory of Algeria, and by the Moroccans on their own territory, till he is expelled therefrom, or falls into the power of one or other nation”.[19] Abd al-Kader would eventually surrender on the 24th of December 1847 to Henri d'Orléans.[32] The Convention of Tangier also stipulated that the boundaries existing between the Turks and Moors at the moment of the conquest should be preserved,[33] and that the Algero-Moroccan boundary agreement that was to follow was to use as its basis the territorial limits of Algeria as they had existed at the time of the Turkish rule.[34]

Treaty of Lalla Maghnia

The Treaty of Lalla Maghnia, signed on March 18, 1845, established a line from the Mediterranean coast to Teniet el-Sassi. The line is based upon the principle that the borders between Morocco and Turkey should remain as the frontier between Algeria and Morocco,[35][36] although the original bounds of the Empire of Morocco and the Turkish domain of Algiers in the nineteenth century were conceptual and approximate rather than linear and exact.[37] The treaty designated that the ksour of Yich and Figuig belong to Morocco, while the ksour of Aïn Séfra, Sfissifa, Asla, Tiout, Chellala, El Bayadh, and Boussemghoun belong to Algeria.[38]

See also

References

- Sondhaus 2004, p. 72.

- Hekking 2020.

- Pennell 2000, p. 42.

- Miller 2013, p. 13.

- Pennell 2000, pp. 42–43.

- Churchill 1867, p. 21.

- Churchill 1867, p. 20.

- Pennell 2000, p. 43.

- Miller 2013, pp. 14–15.

- Miller 2013, p. 17.

- Churchill 1867, p. 230.

- Ideville 1884, p. 100.

- Wagner & Pulszky 1854, p. 367.

- Churchill 1867, pp. 233–234.

- Ideville 1884, p. 113.

- Ideville 1884, p. 114.

- Ideville 1884, p. 116.

- Ideville 1884, p. 118.

- Churchill 1867, p. 236.

- Ideville 1884, p. 119.

- Ideville 1884, pp. 119–120.

- Ideville 1884, p. 121.

- Pennell 2000, p. 49.

- Ideville 1884, p. 125.

- Ideville 1884, p. 133.

- Paterson 1844, p. 520.

- Houtsma 1987, p. 550.

- Ideville 1884, p. 120.

- Paterson 1844, p. 474.

- Bouyerdene 2012, p. 212.

- Bouyerdene 2012, p. 64.

- Bouyerdene 2012, p. 68.

- Ideville 1884, p. 173.

- Trout 1969, p. 20.

- Brownlie 1979, p. 58.

- Clercq 1865, p. 272.

- Brownlie 1979, p. 55.

- Clercq 1865, p. 274.

Bibliography

Books

- Bouyerdene, Ahmed (2012). Emir Abd El-Kader: Hero and Saint of Islam. World Wisdom, Inc.

- Brownlie, Ian (1979). African Boundaries: A Legal and Diplomatic Encyclopaedia. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers.

- Churchill, Charles Henry (1867). The Life of Abdel Kader, Ex-sultan of the Arabs of Algeria: Written from His Own Dictation, and Comp. from Other Authentic Sources. Chapman and Hall.

- Clercq, Alexandre J.H. (1865). Recueil des traites de la France, publié sous les auspices du Ministère des affaires étrangères (in French).

- Hekking, Morgan. The Battle of Isly: Remembering Morocco's Solidarity With Algeria.

- Houtsma, Martijn Theodoor (1987). E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913-1936. Vol. 9. Brill.

- Ideville, Henri (1884). Memoirs of marshal Bugeaud, from his private correspondence and original documents, 1784-1849, ed. from the Fr. by C.M. Yonge.

- Miller, Susan Gilson (2013). A History of Modern Morocco. Cambridge University Press.

- Paterson, Alexander (1844). The Anglo American. Vol. 3.

- Pennell, C. R. (2000). Morocco Since 1830: A History. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (2004). Navies in Modern World History. Reaktion Books.

- Trout, Frank E. (1969). Morocco's Saharan Frontiers. Librairie Droz.

- Wagner, Moritz; Pulszky, Ferencz Aurelius (1854). The Tricolor on the Atlas: Or, Algeria and the French Conquest.

Websites

- Hekking, Morgan (2020). "The Battle of Isly: Remembering Morocco's Solidarity With Algeria". Morocco World News.