Fish in Chinese mythology

Fish are an important motif in Chinese mythology. There are various myths involving fish. Chinese mythology refers to those myths found in the historical geographic area of China. The geographic area of "China" is of course a concept which has evolved of changed through history. Fish in Chinese mythology include myths in Chinese and other languages, as transmitted by Han Chinese as well as other officially recognized 56 minority ethnic groups in China.[1]: 4 The Chinese word for "fish", yu, is a homophone for "abundance", "plenty", and "affluence" (yu 餘);[2] therefore, fishes are a symbol of wealth.[3]: 124 The Chinese dragon is the head of the fish clan. The act of fishing is also an important motif in Chinese mythology and culture.

Cultural significance and symbolism

Yu (fish)

Fishes are a symbol of wealth in Chinese culture.[3]: 124 The Chinese character for fish is yu (traditional Chinese: 魚; simplified Chinese: 鱼; pinyin: yú). It is pronounced with a different tone in modern Chinese, 裕 (yù) means "abundance". Alternatively, 餘, meaning "over, more than", is a true homophone, so the common Chinese New Year greeting appears as 年年有魚 or 年年有餘. Due to the homophony, "fish" mythically becomes equated with "abundance".[3]: 124

Fish and humans

- A picture of a child with a fish expresses the wishes of having an "abundance of high-ranking sons".[3]: 124

- Due to their association with wealth, fishes are eaten on Chinese New Year as they expresses the wishes of being affluent year by year[3]: 124 or "bring abundance of good wishes throughout the year".[2]

Fish and flowers

Fishes and foretelling

- According to ancient Chinese literature, an abundance of fishes in water is believed to foretell a good harvest while the fish swarming up the shoals of rivers is interpreted as a harbinger of civil unrest and rebellion against social order.[3]: 124

Sacrifices and religion

- Fishes were used as sacrifice in China; fish-heads (yutou 魚頭) were sacrificed in Central China to the god of riches as they were believed to symbolize the "beginning of wealth" (yutou 餘頭).[3]: 124 [2]

- The fish is part of the 8 Buddhist symbols:[3]: 126 they are golden fishes which comes in pairs; they are symbols of fertility and represents salvation from suffering.[4]

Sexuality/ marital bliss

- In ancient China, the word yu also meant penis as a secondary meaning, however nowadays, it is the eel which is used instead of fish.[3]: 124

- A metaphor for sexual intercourse in Chinese is "fish and water come together".[3]: 124

- A happily married couple is described as having "the pleasures of fish in water" (yúshuǐ zhīhuān 鱼水之欢[5]: 243 ); therefore pairs of fishes are symbolism of sexual harmony and mutual sexual pleasure.[2][3]: 124 Popular weddings gifts were prints of fishes swimming together.[2]

- When the fish constellation is visible in sky, it is interpreted that the time of "cloud and rains" (yunyu 云雨[5]: 243 ) have passed which means that it is no longer the auspicious time for the Emperor to have sexual intercourse.[3]: 124

Jin yu (Goldfish)

Jinyu (金鱼) is a homophone for "gold in abundance"; therefore, they are perceived as suitable gifts for wedding.[3]: 155 Jinyu is also an homophone of gold (jin 金) and jade (yu 玉),[6] which are both indicators of wealth.[2]

Goldfish and humans

- The depictions of goldfish in a pond (tang 塘) is used to express "may gold and jade fill your house" (jinyu mantang 金玉滿堂) to describe the wishes of having a prosperous household.[2][6]

- A similar depiction is the combination of goldfish in a pond in the courtyard of a house with a wealthy lady with 2 infants and her attendant which symbolically expresses for wish of having "gold (jin) in abundance (yu) fill the whole hall (tang) of the house".[3]: 124

Goldfish and flowers

Goldfish and purse

- The combination of a purse and a goldfish is used to express the wishes for having "gold (goldfish) in abundance in a purse."[3]: 205

Sexuality

Li (carp)

The word carp in Chinese is li (鲤) which is an homophone for advantage (li 利); therefore, carps are used to express wishes for benefits or advantage in business.[3]: 63 Its association with wealth mostly likely comes from the pun liyu (利餘), liyu (鯉魚) also means carp.[2] Li is also an homophone for the character li (力) which means strength, power, and ability.[2]

Carp and humans

- The picture of a carp being sold by a fisherman to a woman with a child expresses the fisherman's wishes for her to have good income and social advancement.[3]: 63, 126

Legends and mythologies

Fish

There is a tale dating in the 1st century BC about a giant fish which swallowed a boat.[3]: 126

Some tales involved drunk men turning into fishes.[3]: 126 There are also tales involving fish-demons (drunk men transformed into fishes) which could sometimes marry women.[3]: 126

Other tales involved fishes turning into birds.[3]: 126

Carp

Carp leaping the Dragon Gate (liyu tiao longmen 鯉魚跳龍門)

Carp (traditional Chinese: 鯉; simplified Chinese: 鲤; pinyin: lǐ) can be transformations of dragons or carp can sometimes change into dragons. According to tradition, a carp that could swim upstream and then leap the falls of the Yellow River at the Dragon Gate (Longmen 龍門) would be transformed into a dragon: this motif symbolizes success in the civil service examinations.[3]: 63 This is the Dragon Gate at the border of Shanxi and Shaanxi where the Yellow River flows through a cleft in the Longmen mountains, supposedly made by Yu the Great, who cut through the mountain. According to one account, all the carp competed at a yearly competition to leap the Longmen falls; those who succeeded were immediately transformed into dragons and flew off into the sky.[7]: 65, 74 Pictures of carp attempting to leap the Longmen falls have been enduringly popular in China. There are other Dragon Gates in the rivers of China, typically with steep narrows, and the mythological geography does not depend upon an actual location. The "flying carp" or "silver carp" (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) is native to China and other parts of Asia. It is a great jumper. Silver carp are strong swimmers and researchers have observed them to jump 1.81-2.24 meters (approximately 5.94 to 7.75 feet) above the surface of the water with an angle of leap of 44-70º.[8] They are quite capable of swimming upstream and leaping over barriers in the water.

Wang Xiang

In one of the stories depicting his exemplar filial piety, Wang Xiang (a young boy) went to the frozen river when his ill mother said that she wanted to eat some carp in winter; there he sat on the ice long enough to melt through the ice and a big carp immediately sprang out of the hole.[3]: 179 In another version, Wang Xiang removed his coat and shirt in the cold and melted the ice when the sat on the ice and cried more and more until the ice melted a hole in the ice through his hot tears and body heat; in this version, it is 2 carps which sprang out of the hole immediately.[9]

Fish-related legends and myths

Other Chinese myths are related to fishes; some Chinese mythological motifs also involve fishermen or fish baskets or a fish trap.

Fuxi

According to Chinese myth, the culture hero Fuxi invented fishing after the Great Flood catching fishes and making nets.[3]: 126 He is also credited for teaching how to eat fish.[3]: 126

A story tells that first Fuxi fished with his hands, but after observing a spider catching insects in its web, he invented the rattan net and used it to catch fish, which skill he passed on to his descendants.[1]: 120

Taigong

Jiang Ziya, the great general and strategist and military mastermind who was key to establishing the Zhou Dynasty, was said to have spent years in his old age fishing, but with a straight hook, or no bait, or with his hook dangling above the water: but, he was fishing for a Lord, not a fish. After Jiang Ziya became the general, he was known as "Taigong" or "the Grand Duke". The degree to which this qualifies as a myth is open to question, but it is certainly a well-known motif.

Fish basket

According to Chinese myth, Fuxi also invented the fish basket, or trap (gu), by weaving bamboo into a cage which had a funnel opening, that was easy for the fish to enter because the big opening was on the outside, but inside it tapered to narrow and exit opening, so it was easy for the fish to get in, but hard to get out.[3]: 127 In other cases the fish basket served more as a net, in which a fish could be scooped from the water and transported to the market.

In one manifestation, Guanyin is pictured as holding a fish basket. This imagery is sometimes considered to have a sexual connotation.

Evolution of Chinese characters

The character for fish (魚) evolved from an ancient pictograph. It is the traditional 195th (out of 216) traditional radical. Over time, the pictographic representations tended to become increasingly stylized, until evolving to the modern standard form:

| script type | example |

|---|---|

| Oracle script |  |

| Bronzeware script |  |

| Great seal script |  |

| Seal script |  |

Gallery

Mongolian bamboo fish basket. Tools and utensils in the Yunnan Nationalities Museum, Kunming, Yunnan, China.

Mongolian bamboo fish basket. Tools and utensils in the Yunnan Nationalities Museum, Kunming, Yunnan, China. Dai bamboo fish basket. Tools and utensils in the Yunnan Nationalities Museum, Kunming, Yunnan, China.

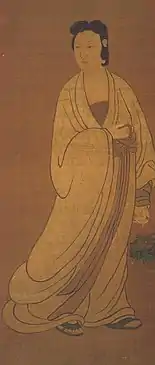

Dai bamboo fish basket. Tools and utensils in the Yunnan Nationalities Museum, Kunming, Yunnan, China. Guanyin of the fish basket - attributed to Zhao Mengfu Yuan dynasty.

Guanyin of the fish basket - attributed to Zhao Mengfu Yuan dynasty. Baskets in Haikou: the flat baskets at center are for holding small fish or shrimp.

Baskets in Haikou: the flat baskets at center are for holding small fish or shrimp.

See also

References

- Yang, Lihui (2005). Handbook of Chinese mythology. Deming An. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-57607-807-8. OCLC 61397586.

- Laing, Ellen Johnston (2017). "Carp and Goldfish as Auspicious Symbols and their Representation in Chinese Popular Prints". Arts Asiatiques. 72 (1): 97–109. doi:10.3406/arasi.2017.1965.

- Eberhard, Wolfram (1986). A dictionary of Chinese symbols : hidden symbols in Chinese life and thought. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 0-7102-0191-5. OCLC 11970928.

- "Symbols, Chinese Mandarin Squares, Online Exhibits, Exhibits, Spurlock Museum, U of I". www.spurlock.illinois.edu. Retrieved 2022-03-12.

- 视角: 翻译学硏究 [Shi jiao : Fan yi xue yan jiu = Perspectives: studies in translatology]. Vol. 2. Cay Dollerup, Ning Wang, 王宁. Beijing: Qing hua da xue chu ban she. 2003. ISBN 7-302-06943-3. OCLC 54376648.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - "Goldfish Exhibition at the Palace of Prolonging Happiness|The Palace Museum". en.dpm.org.cn. 2019. Retrieved 2022-03-12.

- Christie, Anthony (1968). Chinese mythology. London: Hamlyn. ISBN 0-600-00637-9. OCLC 41132.

- Parsons, Glenn R.; Ehlana Stell; Hoover, Jan (2015). "Estimating Burst Swim Speeds and Jumping Characteristics of Silver Carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) Using Video Analyses and Principles of Projectile Physics". doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.3948.2641.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "The twenty-four filial exemplars - chinaculture". en.chinaculture.org. 2013. Retrieved 2022-03-12.