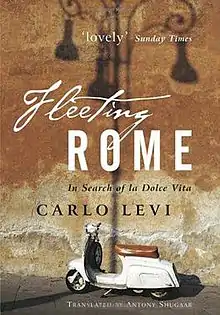

Fleeting Rome

Fleeting Rome: In Search of La Dolce Vita is a posthumous book by Italian Jewish writer and painter Carlo Levi, which collects a number of his writings: correspondence, documents, photographic material from his exhibition catalogues, mainly extracted from the Italian State Central Archive, but also from other sources, such as the Collection of Manuscripts by Modern and Contemporary Authors at the University of Pavia, and the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin, where Levi's Christ Stopped at Eboli is preserved.

| |

| Author | Carlo Levi |

|---|---|

| Original title | Roma fuggitiva: una città e i suoi dintorni |

| Translator | Tony Shugaar |

| Country | Italy |

| Language | Italian |

| Genre | essays, photographic |

| Publisher | John Wiley & Sons |

Publication date | 2004 |

| Media type | Print (Hardback) |

| Pages | 280 pp |

| ISBN | 978-0-470-87183-6 |

| OCLC | 56733361 |

| 945/.6320925 22 | |

| LC Class | DG806.2 .L4813 2004 |

| Preceded by | Carlo Levi inedito: con 40 disegni della cecità (2002) |

| Followed by | Fear of Freedom: With the Essay, "Fear of Painting" (2008) |

The book is a portrayal of everyday life in Rome from the end of World War II to the student movements of the 1960s. Levi skilfully and lovingly sketches a portrait of the Capital city and of its inhabitants through changing seasons and changing times. The author revels in the riotous celebrations for New Year and the many festivals through the year, and rejoices in the beauty of the city in the early morning mist. He introduces a civil servant who spends his days collecting wild asparagus (a perfect employee who takes up no room in his office and causes no scandals), a peasant who wishes to be a writer, a writer who prefers football to talking about literature and thieves who masquerade as policemen. Rome for Levi is a constant joyous adventure that at every encounter and every street presents the casual stroller with a new and hidden delight.

The book has an introduction by Italian critic Giulio Ferroni and quotes as its epigraph a sonnet about Rome written by the baroque writer Francisco de Quevedo:

| A Roma sepultada en sus ruinas[1] | To Rome Buried in Its Ruins |

|---|---|

| Buscas en Roma a Roma oh peregrino! y en Roma misma a Roma no la hallas: |

You seek Rome in Rome, o pilgrim! and in Rome itself you do not find Rome: |

Although this volume of essays was published posthumously, edited by Gigliola De Donato and Luisa Montevecchi, Levi himself intended to gather and publish them with the title Roma fuggitiva (Fleeting Rome), a name that had been inspired by the example of the above verses Quevedo dedicated to Rome.[2] 'Roma fuggitiva' is also the title of a short note among Levi's papers, dated 6 March 1963 from the addition or preamble to the article 'Il popolo di Roma' (The People of Rome). From this note, one learns that Levi took that reference as something like a metaphor for the endurance of that which history in any case had condemned to disappear, that is, that provisional 'restoration' that he had witnessed in the wake of the hopes of the Italian Resistance. These are the words of the article:

The 'fleeting moment' of Rome in these years is the external and evident history of the Italian ruling class, the fragile immobility of a restoration, the apathetic succession of scandals, speculations, deals, enrichments, the apparent triumph of a clerical bourgeoisie, and, flowing through the ruins, much like the river that so deeply moved the Spanish poet, is a glittering river of cars pounding the ancient roadways.[3]

The 1963 note distinguishes, on the one hand, between a Rome that is 'immense and pulpy' and, on the other hand, a 'living precious world', which seems to exist within it, consisting of a 'grey populace' waiting to speak, which is not 'dried out and dead like the stones and the architecture' and which seems to herald a possible world of the future.[4]

Notes

- F. de Quevedo, 'A Roma sepultada en sus ruinas', from 'Parnaso español: Clio', in Poesía varia, edited by J.O. Crosby, Ediciones Cátedra, Madrid, 1997.

- Mistakenly attributed to Luis de Góngora, cf. Fleeting Rome, p. xvi.

- Fleeting Rome, pp. xvii-xviii.

- id. p. xviii, and notes to Ch. I The People of Rome, pp. 239-240.