Fletcher-class destroyer

The Fletcher class was a class of destroyers built by the United States during World War II. The class was designed in 1939, as a result of dissatisfaction with the earlier destroyer leader types of the Porter and Somers classes. Some went on to serve during the Korean War and into the Vietnam War.[3]

_underway_the_1950s.jpg.webp) USS Erben underway in the 1950s | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name |

|

| Builders |

|

| Operators | |

| Preceded by | Gleaves class |

| Succeeded by | Allen M. Sumner class |

| Subclasses | |

| Cost | $6 million |

| Built | 3 March 1941 to 22 February 1945 |

| In commission | 4 June 1942 to 1971 (USN), 2001 (Mexico) |

| Completed | 175 |

| Cancelled | 13 |

| Lost | 19, plus 6 not repaired[1] |

| Preserved | |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Destroyer |

| Displacement | |

| Length | 369.25 ft (112.55 m) wl, 376.5 ft (114.8 m) o/a |

| Beam | 39.5 ft (12.0 m) |

| Draft | 17.5 ft (5.3 m) |

| Propulsion | 60,000 shp (45,000 kW); 4 oil-fired boilers; 2 geared steam turbines; 2 screws |

| Speed | 36.5 knots (67.6 km/h; 42.0 mph) |

| Range | 5,500 nmi (10,200 km; 6,300 mi) at 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph)[2] |

| Boats & landing craft carried | 2 × lifeboats |

| Complement | 329 officers and enlisted |

| Sensors and processing systems | |

| Armament | Varied; see § Armament |

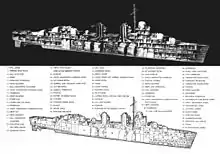

The United States Navy commissioned 175 Fletcher-class destroyers between 1942 and 1944, more than any other destroyer class, and the design was generally regarded as highly successful. The Fletchers had a design speed of 38 knots (70 km/h; 44 mph) and a principal armament of five 5-inch (127 mm) guns in single mounts with ten 21-inch (530 mm) torpedo tubes in two quintuple centerline mounts.[4] The Allen M. Sumner and Gearing classes were Fletcher derivatives.

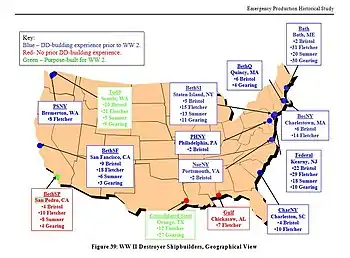

The long-range Fletcher-class ships performed every task asked of a destroyer, from anti-submarine warfare and anti-aircraft warfare to surface action.[5] They could cover the vast distances required by fleet actions in the Pacific and served almost exclusively in the Pacific Theater of Operations during World War II, during which they accounted for 29 Imperial Japanese Navy submarines sunk.[5] In a massive effort, the Fletchers were built by shipyards across the United States, and, after World War II ended, 11 were sold to countries that they had been built to fight against: Italy, Germany, and Japan, as well as other countries, where they had even longer, distinguished careers. Three have been preserved as museum ships in the U.S. and one in Greece.

Description

The Fletcher class (named for Admiral Frank F. Fletcher, Medal of Honor recipient) was the largest destroyer class ordered. It was also one of the most successful and popular with their crews. Compared to earlier classes built for the United States Navy, the Fletchers carried a significant increase in lethal firepower, including anti-aircraft (AA) weapons and increased armor plating; this contributed to greater displacement and overall weight and height increase. Their flush deck construction added structural strength; however, it did make them cramped, as less crew space was available below decks compared with a raised forecastle.

Design

_and_USS_Radford_(DD-446)_at_Federal_SB%2526DD_in_May_1942.jpg.webp)

The Fletcher class was the first generation of destroyers designed after the series of naval treaties that had limited ship designs heretofore. The growth in the design was in part a response to the challenge that had dogged U.S. Navy designs in coping with long range operations in the Pacific Ocean. They were also to carry no fewer than five 5 in (127 mm) guns and ten deck-mounted torpedo tubes on the centerline, allowing them to meet any foreign design on equal terms. Compared to earlier designs, the Fletchers were large, allowing them to adapt to evolving defensive priorities through the addition of two 40-millimetre (1.6 in) Bofors quadruple mount AA guns as well as six 20 mm (0.79 in) Oerlikon dual AA gun positions. This addition to the AA suite required the deletion of the forward quintuple torpedo mount, a change done under the 4 April 1945 anti-kamikaze program.[6]

Fletchers were also much less top-heavy than previous classes, allowing them to take on additional equipment and weapons without major redesign. They were fortunate in catching American production at the right moment, becoming "the" destroyer design, with only the Fletcher-class derivatives, the Allen M. Sumner and Gearing classes, following it.[5]

The first design inputs were in the fall of 1939 from questionnaires distributed around design bureaus and the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. The design parameters were the armaments desired of the next destroyer. As such, the questions were of how many guns, torpedoes, and depth charges were seen as desirable. Also asked was at what point would the design grow large enough to become a torpedo target instead of a torpedo delivery system.[7] The answer that came back was that five 5 in (127 mm) dual-purpose guns, twelve torpedoes, and twenty-eight depth charges would be ideal, while a return to the 1,500-ton designs of the past was seen as undesirable. Speed requirements varied from 35 to 38 knots (65 to 70 km/h; 40 to 44 mph), and shortcomings in the earlier Sims class, which were top-heavy and needed lead ballast to correct this fault, caused the Fletcher design to be widened by 18 in (46 cm) of beam.[8] As with other previous U.S. flush deck destroyer designs, seagoing performance suffered. This was mitigated by deployment to the Pacific Ocean, which is relatively calm compared to the Atlantic.[9]

To achieve 38 knots with a 500-ton increase in displacement, power was increased from 50,000 shp (37,000 kW) to 60,000 shp (45,000 kW) compared to the previous Benson and Gleaves classes. The Fletchers featured air-encased boilers producing steam at 600 psi (4,100 kPa) and 850 °F (450 °C), with two 350 kW steam turbine driven electrical generators and a 100 kW emergency diesel generator.[10] Typically, Babcock & Wilcox boilers and General Electric geared steam turbines were equipped, although other designs and manufacturers were probably used to maximize the rate of production.

Armament

_Bundeswehr_Military_History_Museum%252C_Dresden.jpg.webp)

Main gun armament was five dual-purpose 5-inch/38 caliber (127 mm) guns in single Mk 30 turrets, guided by a Mark 37 Gun Fire Control System, including a Mk 12 fire control radar and a Mk 22 height-finder (replaced by the circular Mk 25 radar postwar) linked by a Mark 1A Fire Control Computer and stabilized by a Mk 6 8500 rpm gyroscope.

Ten 21 in (530 mm) torpedo tubes were fitted in two quintuple mounts amidships, firing the 21-inch Mark 15 torpedo. Anti-submarine armament was two racks for 300-pound (140 kg) depth charges at the stern and six K-gun 300-pound depth charge throwers amidships.

Anti-aircraft armament initially was light, with a quadruple 1.1"/75 caliber gun located in an elevated tub between the number three and four 5-inch gun mounts and six Oerlikon 20 mm cannons (two in front of and below the bridge and four amidships). In June 1942, the 1.1" gun was replaced by a twin Bofors 40 mm gun mount; in some ships, another twin mount may have been added on the fantail between the depth charge racks. In February 1943, the fantail-mounted Bofors was removed and one twin mount was placed on each side of the aft funnel, bringing the total number of 40 mm to six.

In 1942 and 1943, the number of Oerlikon cannons was steadily increased with ships modified before leaving the shipyard with a seventh 20 mm mount in front of the bridge behind the number two 5" gun mount and anywhere from one to three mounts on the flying bridge depending upon the configuration of the ship. In combat, commanders often requisitioned additional guns with some ships mounting up to thirteen 20 mm cannons. In June and July 1943, two more twin Bofors mounts were added in place of the 20 mm cannons in front of and below the bridge, giving a total of ten. With this modification, the Oerlikon cannons were rearranged and their number was standardized at seven; four amidships and three in a heart-shaped mount on the fantail.

Due to the increasing threat from kamikaze attacks, beginning in July 1945 some ships returning to the United States for refits received further anti-aircraft modifications. The forward set of torpedo tubes was removed, providing space to replace the two amidships twin 40 mm guns with two quadruple mountings (for a total of fourteen). The seven single 20 mm guns were replaced with six twin mounts (four amidships and two on the fantail.

Three (Pringle, Stevens and Halford) were built with aircraft catapults after deletion of the rear torpedo tube mount and the number 3 5-inch gun mount. This alteration was not a success and was not repeated. These three destroyers were later converted to the regular Fletcher-class configuration.

Service

Nineteen Fletchers were lost during World War II; six more were damaged, evaluated as constructive total losses, and not repaired.[1] Postwar, the remainder were decommissioned and put into reserve.

Ships lost

- De Haven, sunk by Japanese aircraft off Savo Island, 1 February 1943

- Strong, sunk by a Japanese destroyer group operating in the Kula Gulf, 5 July 1943

- Chevalier, scuttled after being torpedoed by a Japanese destroyer and accidentally rammed in the Naval Battle of Vella Lavella, 6 October 1943

- Brownson, sunk by Japanese aircraft off Cape Gloucester, 26 December 1943

- Hoel, sunk by Japanese surface ships in the Battle off Samar, 25 October 1944

- Johnston, sunk by Japanese surface ships in the Battle off Samar, 25 October 1944

- Abner Read, sunk by kamikazes in Leyte Gulf, 1 November 1944

- Spence, foundered in Typhoon Cobra, 18 December 1944

- Halligan, lost to a mine off Okinawa, 26 March 1945

- Bush, sunk by kamikazes off Okinawa, 6 April 1945

- Colhoun, sunk by kamikazes off Okinawa, 6 April 1945

- Pringle, sunk by kamikazes off Okinawa, 16 April 1945

- Little, sunk by kamikazes off Okinawa, 3 May 1945

- Luce, sunk by kamikazes off Okinawa, 4 May 1945

- Morrison, sunk by kamikazes off Okinawa, 4 May 1945

- Longshaw, scuttled after running aground and receiving heavy shore fire south of Naha, Okinawa, 18 May 1945

- William D. Porter, sunk by a kamikaze off Okinawa, 10 June 1945

- Twiggs, sunk by kamikazes off Okinawa, 16 June 1945

- Callaghan, sunk by Yokosuka K5Y kamikaze biplanes off Okinawa, 28 July 1945

- Newcomb, damaged by kamikazes off Okinawa, 6 April 1945. Decommissioned, 20 November 1945. Sold for scrap, 28 March 1946.

- Leutze, damaged by kamikazes off Okinawa, 6 April 1945. Decommissioned, 6 December 1945. Sold for scrap, 17 June 1947.

- Hutchins, damaged by a suicide boat off Okinawa, 27 April 1945. Decommissioned, 30 November 1945. Sold for scrap, January 1948.

- Haggard, damaged by kamikazes off Okinawa, 29 April 1945. Decommissioned, 1 November 1945. Sold for scrap, 3 March 1946.

- Evans, damaged by kamikazes off Okinawa, 11 May 1945. Decommissioned, 7 November 1945. Sold for scrap, 11 February 1947.

- Thatcher, damaged by kamikazes off Okinawa, 20 May 1945. Decommissioned, 23 November 1945. Sold for scrap, 23 January 1948.

Korean War

With the outbreak of the Korean War many were returned to active duty. During this time 39 were refitted under project SCB 74A, reducing their overall main armament and the number of torpedo tubes to accommodate other weapons. A new ahead-throwing weapon called Weapon Alpha was installed in many of the ships. Others carried trainable Hedgehogs. Eighteen ships were redesignated as escort destroyers (DDE), optimized for anti-submarine warfare; these reverted to destroyer (DD) designation in 1962.

Other navies

Many of the ships were sold to other navies during the mid-1950s, including:

| Country | No. sold |

|---|---|

| Argentina | 5[lower-alpha 1] (see Brown-class destroyer) |

| Brazil | 7 (see Pará-class destroyer) |

| Chile | 2 |

| Colombia | 1 |

| Greece | 7 |

| Italy | 3 (see Fante-class destroyer) |

| Japan | 2 (see Ariake-class destroyer) |

| Mexico | 2 |

| Peru | 2 |

| South Korea | 3 (see Chungmu-class destroyer) |

| Spain | 5 (see Lepanto-class destroyer) |

| Republic of China (Taiwan) | 4 |

| Turkey | 4 |

| West Germany | 6 (see Zerstörer 1-class destroyer) |

Any remaining were broken up in the 1970s. The last Fletcher in service, BAM Cuitlahuac (ex-John Rodgers), left the Mexican navy in 2001, meaning the total service life of the Fletchers stretched over almost six decades and into the 21st century.[1]

| Country | Pennant | Ship name | Former name | Acquired | Fate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | D-20 | ARA Almirante Brown | USS Heermann | 14 August 1961 | Scrapped in 1982 |

| D-21 | ARA Espora | USS Dortch | 16 August 1961 | Scrapped in 1977 | |

| D-22 | ARA Rosales | USS Stembel | 7 August 1961 | Scrapped in 1982 | |

| D-23 | ARA Almirante Domecq Garcia | USS Braine | 17 August 1971 | Sunk as a target on 7 October 1983 | |

| D-24 | ARA Almirante Storni | USS Cowell | 17 August 1971 | Scrapped in 1982 | |

| Brazil | D27 | Para | USS Guest | 5 June 1959 | struck in 1978, sunk as a target on 23 February 1983 |

| D28 | Paraiba | USS Bennett | 15 December 1959 | struck and scrapped in 1978 | |

| D29 | Paraná | USS Cushing | 20 July 1961 | struck in 1973 and scrapped in 1982 | |

| D30 | Pernambuco | USS Hailey | 20 July 1961 | sunk as a target about 1982 | |

| D31 | Piaui | USS Lewis Hancock | 1 August 1967 | struck and scrapped in 1989 | |

| D32 | Santa Catarina | USS Irwin | 10 May 1968 | struck in 1988 and sunk as a target in 1990 | |

| D33 | Maranhao | USS Shields | 1 July 1972 | struck and scrapped in 1990 | |

| Chile | D-14 | Blanco Encalada | USS Wadleigh | 26 July 1962 | struck in 1982, sunk as a target on 28 September 1991 |

| D-15 | Cochrane | USS Rooks | 26 July 1962 | struck in 1983, scrapped | |

| N/A | — | USS Charles J. Badger | 10 May 1974 | scrapped and cannibalized | |

| Colombia | DD-01 | ARC Antioquia | USS Hale | 23 January 1961 | struck in 1973, scrapped |

| Germany | D 170 | Zerstörer 1 | USS Anthony | 1 January 1958 | struck in 1976, sunk as a target on 16 May 1979 |

| D 171 | Zerstörer 2 | USS Ringgold | 14 July 1959 | transferred to Hellenic Navy on 18 September 1981 | |

| D 172 | Zerstörer 3 | USS Wadsworth | 6 October 1959 | transferred to Hellenic Navy on 15 October 1980 | |

| D 178 | Zerstörer 4 | USS Claxton | 16 December 1959 | transferred to Hellenic Navy in February 1981 | |

| D 179 | Zerstörer 5 | USS Dyson | 17 February 1960 | transferred to Hellenic Navy in February 1982 | |

| D 180 | Zerstörer 6 | USS Charles Ausburne | 12 April 1960 | scrapped in October 1968 | |

| Greece | D-06 | Aspis | USS Conner | 15 September 1959 | struck in 1991, scrapped in 1997 |

| D-16 | Velos | USS Charrette | 16 June 1959 | Active - In commission as museum ship since 1991 | |

| D-28 | Thyella | USS Bradford | 27 September 1962 | struck in 1981, scrapped in 1981 | |

| D-42 | Kimon | USS Ringgold | 18 September 1981 | struck in 1993, scrapped in 1993 | |

| D-56 | Lonchi | USS Hall | 9 February 1960 | struck on 10 October 1990, scrapped in 1997 | |

| D-63 | Navarinon | USS Brown | 27 September 1962 | struck in 1981, scrapped in 1981 | |

| D-65 | Nearchos | USS Wadsworth | 15 October 1980 | struck in 1991, scrapped in 1991 | |

| D-85 | Sfendoni | USS Aulick | 21 August 1959 | struck in 1991, scrapped in 1997 | |

| N/A | — | USS Claxton | February 1981 | scrapped and cannibalized | |

| N/A | — | USS Dyson | February 1982 | scrapped and cannibalized | |

| Italy | D-560 | Lanciere | USS Taylor | 2 July 1969 | struck in 1971 and cannibalized to provide spare parts for her sisters in Italian service |

| D-561 | Fante | USS Walker | 2 July 1969 | struck and broken up for scrap in 1977 | |

| D-555 | Geniere | USS Prichett | 17 January 1970 | struck and broken up for scrap in 1975 | |

| Japan | DD-183 | JDS Ariake | USS Heywood L. Edwards | 10 March 1959 | struck in 1974, scrapped in 1976 |

| DD-184 | JDS Yūgure | USS Richard P. Leary | 10 March 1959 | struck in 1974, scrapped on 1 July 1976 | |

| Mexico | E-01 | ARM Cuauhtémoc | USS Harrison | 19 August 1970 | Dismantled |

| E-02 | ARM Cuitláhuac | USS John Rodgers | 19 August 1970 | Scrapped in 2011 | |

| Spain | D21 | Lepanto | USS Capps | 15 May 1957 | struck in 1985, scrapped |

| D22 | Almirante Ferrandíz | USS David W. Taylor | struck in 1987, scrapped | ||

| D23 | Almirante Valdés | USS Converse | 1 July 1959 | struck in 1986, scrapped in 1988 | |

| D24 | Alcalá Galiano | USS Jarvis | 3 November 1960 | struck in 1988, scrapped | |

| D25 | Jorge Juan | USS McGowan | 1 December 1960 | struck in 1988, scrapped | |

| South Korea | DD-91 | ROKS Chung Mu | USS Erben | 16 May 1963 | possibly scrapped |

| DD-92 | ROKS Seoul | USS Halsey Powell | 27 April 1968 | struck in 1982, scrapped in 1982 | |

| DD-93 | ROKS Pusan | USS Hickox | 15 November 1968 | struck in 1989, scrapped in 1989 | |

| Taiwan (Republic of China) | DDG-108 | ROCS Kwei Yang | USS Twining | 16 August 1971 | struck in 1999, scrapped |

| DDG-109 | ROCS Ching Yang | USS Mullany | 6 October 1971 | struck in 1999, sunk as a target on 1 November 2001 | |

| DDG-918 | ROCS An Yang | USS Kimberly | 1 June 1967 | struck in 1999, sunk as a target on 14 October 2003 | |

| DDG-919 | ROCS Kuen Yang | USS Yarnall | 10 June 1968 | struck in 1999, scrapped |

Surviving ships

Four Fletcher-class destroyers are preserved as museum ships. Three are in the United States and one is in Greece, although only Kidd retains her World War II configuration.

Velos is the only vessel still in commission. Velos alongside G. Averof are ceremonially commissioned by the Hellenic Navy having Palaio Faliro as their base. Their crew are active Officers of Hellenic Navy. Velos still retains its complete armament and equipment (as modernized in 1950s). In September 2019 its crew took her to Thessaloniki for a short 3-month stay. As of October 2020, she remains in Thessaloniki and she has been visited by over 157.000 visitors.

All three American museum ships have been designated as National Historic Landmarks.[11][12][13]

Surviving ships

- USS The Sullivans (DD-537), in Buffalo, New York

- USS Kidd (DD-661), in Baton Rouge, Louisiana

- USS Cassin Young (DD-793), in Boston, Massachusetts

- Velos (D16), in Palaio Faliro, Greece

Surviving parts

- USS Fletcher (DD-445), in National Museum of the United States Navy, Washington, D.C.[14]

- USS Radford (DD-446), in USS Orleck Naval Museum, Louisiana[15]

- USS Nicholas (DD-449), in the Veterans Memorial Museum in Chehalis, Washington[16] and at Center House, Marine Barracks, Washington, D.C.[17]

- USS Renshaw (DD-499), in Portsmouth Naval Shipyard Museum, Virginia

- USS Foote (DD-511), in National Museum of the Pacific War, Texas[18]

- USS Hailey (DD-556), on a naval base in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

- USS Smalley (DD-565), in Freedom Park, Omaha, Nebraska

- USS Dyson (DD-572), in Heritage Veterans Memorial Plaza, Texas[19]

- USS Izard (DD-589), in Ohio State University, Ohio[20]

- USS Caperton (DD-650), aboard USS Kidd (DD-661), in Baton Rouge, Louisiana

- USS Knapp (DD-653), in Columbia River Maritime Museum, Oregon[21]

- USS Chauncey (DD-667), aboard USS Kidd (DD-661), in Baton Rouge, Louisiana

- USS Monssen (DD-798), in Freedom Park, Nebraska

- Zerstörer 1 (D170) or Zerstörer 6 (D180), in Bundeswehr Military History Museum, Dresden[22]

- Zerstörer 6 (D180), in Marbeck-Heiden train station, Marbeck[23]

- ROCS Ching Yang (DD-9), in Yuanzhiluxiuxian Park, Tainan City[24] and Táinán jūn shǐ gōngyuán Park, Tainan City

- ROKS Chungmu (DD-91), in Yongsan War Memorial, Seoul[25][26]

- TCG İçel (D-344), in Derince Naval Base, Kocaeli, Turkey.

Notes

In 2018, Kidd was used as the filming location for the fictional USS Keeling DD-548 (codenamed Greyhound), from C.S. Forester's novel The Good Shepherd, in her appearance in the book's 2020 cinematic adaptation, Greyhound.[27][28]

On 14 April 2022, museum ship USS The Sullivans sank at her Pier in the Buffalo Naval Park. The depth of water prevented complete sinking. Since then, the ship has been refloated and restoration of the ship's electric system and interior spaces is ongoing.[29]

Ships in class

References

- destroyerhistory.org: Fletcher class

- "USS Bush-Fletcher class". Retrieved 12 April 2007.

- Friedman, Norman (2004). US Destroyers: An Illustrated Design History (Revised ed.). Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. pp. 111–112.

- Friedman p. 472.

- Friedman pp. 111–112.

- Friedman, p. 118.

- Friedman, p. 112.

- Friedman, pp. 112–113.

- Friedman, p. 111.

- George Stewart (31 July 2013). "Life on a Fletcher Class Destroyer in the 1950's".

- Harry A. Butowsky (May 1985). "USS The Sullivans (DD-537)". National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination. National Park Service.

- "NHL nomination for USS Kidd". National Park Service. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- "NHL nomination for USS Cassin Young (destroyer)". National Park Service. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- "USS Fletcher (DD-445, later DDE-445)". public1.nhhcaws.local. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- "radford-museum – USS Orleck DD-886". Archived from the original on 13 June 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- Celene Fitzgerald. "Veterans' Museum to Receive Historic Navy Ship's Mast". The Chronicle. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- "Marine Barracks, Washington Tour Guide - Officer's Walk" (PDF). DVIDS Hub. 4 December 2014. p. 29. Retrieved 3 August 2023.

- "USS KIDD Veterans Museum". www.facebook.com. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- "USS Dyson Bell". www.verduinwebs.com. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- "Flag Honors Hall of Fame | Naval ROTC Alumni Society". Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- "USS Knapp - bridge: Fujifilm X System / SLR Talk Forum: Digital Photography Review". www.dpreview.com. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- "Fletcher-Klasse Mark-30 Turm Walkaround (124) Scalenews". Scalenews (in German). Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- "Handfestes Phänomen am Bahnhof Marbeck". Fletcher-oldies (in German). Archived from the original on 29 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- USS Sullivan Museum's Instagram Page

- 국방일보. DEMA. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

- 전쟁기념관 #5 - 용산전쟁기념관 전시실 3. 나혼자닷컴. 26 January 2010. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

- J.D. Simkins (March 2020). "'Greyhound' trailer puts Tom Hanks at the helm of a Nazi-hunting WWII destroyer". Military Times.

- Jeremy Krail; Sydney Kern (9 April 2018). "Tom Hanks' WWII drama filming aboard USS Kidd this week". WBRZ. Louisiana Television Broadcasting LLC.

- Jordan, Erin (11 November 2022). "USS The Sullivans no longer sinking, but set for more repairs". The Gazette (Cedar Rapids, Iowa). Retrieved 29 January 2023.

Bibliography

- Bauer, K. Jack; Roberts, Stephen S. (1991). Register of Ships of the U.S. Navy, 1775–1990: Major Combatants. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-26202-0.

- Davis, Rick E. & Wright, Christopher C. (2010). "USN Aircraft-Handling Destroyers 1919 to 1943, Part I: 1919–1941". Warship International. XLVII (3): 265–278. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Friedman, Norman (2004). US Destroyers: An Illustrated Design History (Revised ed.). Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-442-3.

- Gardiner, Robert; Chesneau, Roger (1980). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1922–1946. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-83170-303-2.

- Gardiner, Robert; Chumbley, Stephen (1995). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1947-1995. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 1-55750-132-7.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (1965). U.S. Warships of World War II. London: Ian Allan Ltd. ISBN 0-7110-0157-X.

- Toby, A. Steven (2015). "Note on High Speed Destroyers' Maneuverability". Warship International. LII (1): 24–27. ISSN 0043-0374.

- This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships.