Fluorometer

A fluorometer, fluorimeter or fluormeter is a device used to measure parameters of visible spectrum fluorescence: its intensity and wavelength distribution of emission spectrum after excitation by a certain spectrum of light.[1] These parameters are used to identify the presence and the amount of specific molecules in a medium. Modern fluorometers are capable of detecting fluorescent molecule concentrations as low as 1 part per trillion.

_in_the_field..jpg.webp)

Fluorescence analysis can be orders of magnitude more sensitive than other techniques. Applications include chemistry/biochemistry, medicine, environmental monitoring. For instance, they are used to measure chlorophyll fluorescence to investigate plant physiology.

Components and design

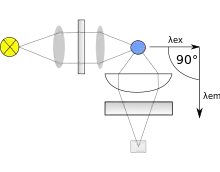

Typically fluorometers utilize a double beam. These two beams work in tandem to decrease the noise created from radiant power fluctuations. The upper beam is passed through a filter or monochromator and passes through the sample. The lower beam is passed through an attenuator and adjusted to try and match the fluorescent power given off from the sample. Light from the fluorescence of the sample and the lower, attenuated beam are detected by separate transducers and converted to an electrical signal that is interpreted by a computer system.

Within the machine the transducer that detects fluorescence created from the upper beam is located a distance away from the sample and at a 90-degree angle from the incident, upper beam. The machine is constructed like this to decrease the stray light from the upper beam that may strike the detector. The optimal angle is 90 degrees. There are two different approaches to handling the selection of incident light that gives way to different types fluorometers. If filters are used to select wavelengths of light, the machine is called a fluorometer. While a spectrofluorometer will typically use two monochromators, some spectrofluorometers may use one filter and one monochromator. Where, in this case, the broad band filter acts to reduce stray light, including from unwanted diffraction orders of the diffraction grating in the monochromator.

Light sources for fluorometers are often dependent on the type of sample being tested. Among the most common light source for fluorometers is the low-pressure mercury lamp. This provides many excitation wavelengths, making it the most versatile. However, this lamp is not a continuous source of radiation. The xenon arc lamp is used when a continuous source of radiation is needed. Both of these sources provide a suitable spectrum of ultraviolet light that induces chemiluminescence. These are just two of the many possible light sources.

Glass and silica cuvettes are often the vessels in which the sample is placed. Care must be taken to not leave fingerprints or any other sort of mark on the outside of the cuvette, because this can produce unwanted fluorescence. "Spectro grade" solvents such as methanol are sometimes used to clean the vessel surfaces to minimize these problems.

Uses

Dairy industry

Fluorimetry is widely used by the dairy industry to verify whether pasteurization has been successful. This is done using a reagent which is hydrolysed to a fluorophore and phosphoric acid by alkaline phosphatase in milk.[2] If pasteurization has been successful then alkaline phosphatase will be entirely denatured and the sample will not fluoresce. This works because pathogens in milk are killed by any heat treatment which denatures alkaline phosphatase.[3][4]

Fluorescence assays are required by milk producers in the UK to prove successful pasteurization has occurred,[5] so all UK dairies contain fluorimetry equipment.

Protein aggregation and TSE detection

Thioflavins are dyes used for histology staining and biophysical studies of protein aggregation.[6] For example, thioflavin T is used in the RT-QuIC technique to detect transmissible spongiform encephalopathy-causing misfolded prions.

Oceanography

.jpg.webp)

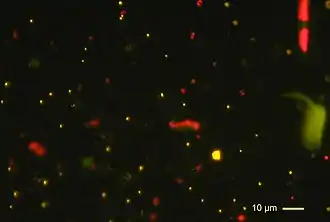

Fluorometers are widely used in oceanography to measure chlorophyll concentrations based on chlorophyll fluorescence by phytoplankton cell pigments. Chlorophyll fluorescence is a widely-used proxy for the quantity (biomass) of microscopic algae in the water. In the lab after water sampling, researchers extract the pigments out of a filter that has phytoplankton cells on it, then measure the fluorescence of the extract in a benchtop fluorometer in a dark room.[7] To directly measure chlorophyll fluorescence "in situ" (in the water), researchers use instruments designed to measure fluorescence optically (for example, sondes with extra electronic optical sensors attached). The optical sensors emit blue light to excite phytoplankton pigments and make them fluoresce or emit red light. The sensor measures this induced fluorescence by measuring the red light as a voltage, and the instrument saves it to a data file. The voltage signal of the sensor gets converted to a concentration with a calibration curve in the lab, using either red-colored dyes like Rhodamine, standards like Fluorescein, or live phytoplankton cultures.[8]

Ocean chlorophyll fluorescence is measured on research vessels, small boats, buoys, docks, and piers all over the world. Fluorometry measurements are used to map chlorophyll concentrations in support of ocean color remote sensing. Special fluorometers for ocean waters can measure properties beyond the total amount of fluorescence, such as the quantum yield of photochemistry, the timing of the fluorescence, and the fluorescence of cells when subjected to increasing amounts of light.[9] Aquaculture operations such as fish farms us fluorometers to measure food availability for filter feeding animals like mussels[10] and to detect the onset of Harmful Algal Blooms (HABs) and/or "red tides" (not necessarily the same thing).[11]

Molecular biology

Fluorometers can be used to determine the nucleic acid concentration in a sample.[12]

Fluorometer types

There are two basic types of fluorometers: the filter fluorometers and spectrofluorometer. The difference between them is the way they select the wavelengths of incident light; filter fluorometers use filters while spectrofluorometers use grating monochromators. Filter fluorometers are often purchased or built at a lower cost but are less sensitive and have less resolution than spectrofluorometers. Filter fluorometers are also capable of operation only at the wavelengths of the available filters, whereas monochromators are generally freely tunable over a relatively wide range. The potential disadvantage of monochromators arises from that same property, because the monochromator is capable of miscalibration or misadjustment, whereas the wavelength of filters are fixed when manufactured.

See also

- Fluorescence spectroscopy, for a fuller discussion of instrumentation

- Chlorophyll fluorescence, to investigate plant ecophysiology.

- Integrated fluorometer to measure gas exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence of leaves.

- Radiometer, to measure various electromagnetic radiation

- Spectrometer, to analyze spectrum of electromagnetic radiation

- Scatterometer, to measure scattered radiation

- Microfluorimetry, to measure fluorescence on a microscopic level

- Interference filter, thin film filters that work by optical interference, showing how they can be tuned in some cases

References

- "Fluorescence Spectrophotometry". Encyclopedia of Life Sciences. Macmillan Publishers Ltd. 2002.

- Langridge, E W. The Determination of Phosphatase Activity. Quality Management Ltd. Retrieved 2013-12-20.

- Kay, H. (1935). "Some Results of the Application of a Simple Test for Efficiency of Pasteurisation". The Lancet. 225 (5835): 1516–1518. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)12532-8.

- Hoy, W. A.; Neave, F. K. (1937). "The Phosphatase Test for Efficient Pasteurisation". The Lancet. 230 (5949): 595. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)83378-4.

- BS EN ISO 11816-1:2013

- Biancalana M, Koide S (July 2010). "Molecular mechanism of Thioflavin-T binding to amyloid fibrils". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Proteins and Proteomics. 1804 (7): 1405–12. doi:10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.04.001. PMC 2880406. PMID 20399286.

- Holm-Hansen, Osmund; Lorenzen, Carl J.; Holmes, Robert W.; Strickland, John D. H. (1965). "Fluorometric Determination of Chlorophyll". ICES Journal of Marine Science. 30 (1): 3–15. doi:10.1093/icesjms/30.1.3.

- Earp, Alan (2011). "Review of fluorescent standards for calibration of in situ fluorometers: Recommendations applied in coastal and ocean observing programs". Optics Express. 19 (27): 26768–26782. doi:10.1364/OE.19.026768. hdl:10453/18163. PMID 22274260.

- Falkowski, Paul G.; Lin, Hanzhi; Gorbunov, Maxim Y. (14 August 2017). "What limits photosynthetic energy conversion efficiency in nature? Lessons from the oceans". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. The Royal Society. 372 (1730): 20160376. doi:10.1098/rstb.2016.0376. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 5566876. PMID 28808095.

- Ogilvie, Shaun C.; Ross, Alex H.; Schiel, David R. (2000). "Phytoplankton biomass associated with mussel farms in Beatrix Bay, New Zealand". Aquaculture. 181 (1–2): 71–80. doi:10.1016/S0044-8486(99)00219-7.

- Anderson, Donald M.; Anderson, Per; Bricelj, V. Monica; Cullen, John J.; Rensel, J. E. Jack (2001). Monitoring and Management Strategies for Harmful Algal Blooms in Coastal Waters, APEC #201-MR-01.1 (PDF). Paris: Asia Pacific Economic Program, Singapore, and Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission Technical Series No. 59.

- Mészáros, Éva (2021). "Determine the concentration and purity of nucleic acids". INTEGRA Biosciences.