Flushing Meadows–Corona Park

Flushing Meadows–Corona Park, often referred to as Flushing Meadows Park, or simply Flushing Meadows, is a public park in the northern part of Queens in New York City, New York, U.S. It is bounded by I-678 (Van Wyck Expressway) on the east, Grand Central Parkway on the west, Flushing Bay on the north, and Union Turnpike on the south. Flushing Meadows–Corona Park is the fourth-largest public park in New York City, with a total area of 897 acres (363 ha).

| Flushing Meadows–Corona Park | |

|---|---|

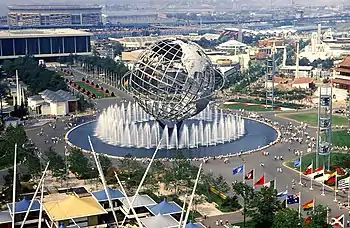

The Unisphere and New York State Pavilion | |

| Type | Public park |

| Location | Queens, New York, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 40°44′45″N 73°50′41″W |

| Area | 897 acres (363 ha) |

| Created | 1939 |

| Operated by | NYC Parks |

| Status | Open all year |

| Public transit access | Subway: LIRR: Port Washington Branch to Mets–Willets Point Bus: Q48, Q58, Q64, Q88 |

Until the 19th century, the site consisted of wetlands straddling the Flushing River, which traverses the region from north to south. Starting in the first decade of the 20th century, it was used as a dumping ground for ashes, since at the time, the land was so far away from the developed parts of New York City as to be considered almost worthless. New York City Parks Commissioner Robert Moses first conceived the idea of developing a large park in Flushing Meadow in the 1920s as part of a system of parks across eastern Queens. Flushing Meadows–Corona Park was created as the site of the 1939 New York World's Fair and also hosted the 1964 New York World's Fair. Following the 1964 fair, the park fell into disrepair, although some improvements have taken place since the 1990s and 2000s.

Flushing Meadows–Corona Park retains much of the layout from the 1939 World's Fair. Its attractions include the USTA Billie Jean King National Tennis Center, the current venue for the US Open tennis tournament; Citi Field, the home of the New York Mets baseball team; the New York Hall of Science; the Queens Museum; the Queens Theatre in the Park; the Queens Zoo; the Unisphere; and the New York State Pavilion. It formerly contained Shea Stadium, demolished in 2009. The Flushing River continues to run through the park, and two large lakes called Meadow and Willow Lakes take up much of the park's area south of the Long Island Expressway.

Flushing Meadows–Corona Park is owned and maintained by New York City Department of Parks and Recreation, also known as NYC Parks. Private, non-profit groups such as the Flushing Meadows–Corona Park Conservancy and the Alliance for Flushing Meadows–Corona Park provide additional funds, services, and support. The park is at the eastern edge of the area encompassed by Queens Community Board 4.[1]

Etymology

The park is named after the nearby neighborhoods of Flushing and Corona, which are separated by the park. The name "Flushing" is a corruption of the port town of Vlissingen in the Netherlands. By the 19th century, the word "flushing" had become associated with "a cleansing by rushing water".[2] "Corona" was added to the name during the 1964 New York World's Fair.[3]

History

Early years

During at least three glacial periods, including the Wisconsin glaciation around 20,000 years ago, ice sheets advanced south across North America carving moraines, valleys, and hills. In particular, bays and estuaries were formed along the north shore of Long Island. During glaciation, what is now Flushing Meadows Park was formed just north of the terminal moraine that runs across Long Island, which consisted of sand, gravel, clay and boulders.[4] The moraine created a drainage divide, with rivers north of the moraine such as the future Flushing River emptying into the north shore.[5] The Flushing Meadows site became a glacial lake, and then a salt marsh after the ice melted.[6] Prior to glaciation, the Flushing River valley was used by the Hudson River to drain southward into the Atlantic Ocean.[7] Through the 19th century, the site continued to consist of wetlands straddling Flushing River.[8] Species inhabiting the site included waterfowl and fiddler crab, with fish using water pools for spawning.[9]

The area was first settled by Algonquian Native Americans of Long Island (referred to erroneously as "Mantinecocks").[10][11] They consisted of the "Canarsee" and "Rockaway" Lenape groups,[12] which inhabited coastal wetlands across Queens and Brooklyn.[11][13] Beginning in 1640, Dutch settlers moved into the area, establishing the town of Newtown to the west of the site (which would become Elmhurst, Corona, and other areas in western Queens), and the town of Flushing to the east.[10] The meadows became known as the Corona Meadows.[14] By 1666, the Native American population had been displaced from the Flushing Meadows site by European settlers, although a deed reserved the right to hunt on the land for the Native Americans. Several wealthy landowners began building farmhouses on the site in the mid-to-late 17th century. The meadows provided numerous natural resources for settlers, including timber, water, fertile soil, and grass and hay for grazing domestic animals.[14] During the American Revolution, a farmhouse on the site of the modern World's Fair Marina was used as a headquarters for British forces.[15]

By the 1800s, primitive roads were established crossing the meadows, running along what are now Northern Boulevard and the Long Island Expressway.[16] Several railroads were also laid through the site, including lines of the Flushing and North Side Railroad (today's LIRR Port Washington Branch and the defunct Whitestone Branch).[17] Shortly after the American Civil War, the meadows became a waterfront resort due to its natural beauty, and affluent New Yorkers constructed homes in the area.[10] British saloon-keeper Harry Hill built the Flushing Bay Hotel and Pavilion on the future marina site.[15]

Filling and use as a dumping ground

Around 1907, contractor Michael Degnon, whose firm constructed the Williamsburg Bridge, the Cape Cod Canal, and the Steinway subway tunnel (used by today's 7 and <7> trains),[18] purchased large tracts of marsh near Flushing Creek.[19][20] At the time, the land was considered "all but worthless".[21] Degnon envisioned using the site to create a large industrial port around Flushing Bay, similar to a terminal he developed in Long Island City.[20][22] By 1911, Degnon had created a plan along with the United States Department of War and the Queens Topographical Bureau. The plan envisioned widening Flushing River and creating docks for ships, with numerous factories and freight facilities. Meanwhile, the residential areas of Corona were expected to become the primary residence for factory workers.[23][24]

To create the port, beginning in 1910 Degnon proceeded to fill the land using household coal ash and street sweepings from Brooklyn. Degnon set up two companies of his own, one of which was contracted with the New York City Department of Sanitation.[25] He also contracted the Brooklyn Ash Removal Company, owned by Fishhooks McCarthy, a member of the corrupt Tammany Hall political machine.[26] Residential ash was collected via trolleys of the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company, and loaded onto freight trains which traveled via the Long Island Rail Road branches, or other trolleys, which hauled the refuse to Corona.[25] The operation was referred to as a citywide refuse "conveyor belt," while the trains were nicknamed the "Talcum Powder Express" because they often ran uncovered and deposited soot onto the surroundings.[27] The northern end of the site was filled via now-conventional means, using dirt pumped from Flushing Bay which was being dredged to a lower depth. Material from the bay was extracted by an offshore hydraulic machine, and funneled through a 1,500-foot (460 m) pipe across Northern Boulevard, before being deposited onto the wetlands.[28] The filling for the north meadow was complete in 1916.[29]

The prospect of creating a port was halted in 1917 by material restrictions caused by World War I, and a lack of federal support for the project. Industrial activities in the borough were fulfilled by existing terminals in Long Island City, Maspeth, Flushing, and College Point.[30] Dumping of ash into the meadows continued, however, fueled by the increased use of garbage incinerators in the city.[31] The area became known as the Corona Dump or Corona Ash Dumps.[32] During nearly 30 years of filling, around 50 million cubic yards of ash and waste were dumped onto the meadows site.[33] One particular mound of ash rose 90 feet (27 m) high and was called "Mount Corona".[34] Other mounds rose 40–50 feet (12–15 m) high.[35] The average thickness of the ash was 30 feet (9.1 m).[36]

The dumps drew the ire of local residents, due to strong odors and being deemed unsightly, along with increasing rat infestations in the local neighborhoods.[37][38] Much of the "street sweepings" collected consisted of horse manure from horse-drawn carriages. In addition, many residents simply threw out normal garbage along with the coal ashes.[39] The meadows were also considered one of the worst breeding grounds for mosquitoes in the city.[40][41] The dump was famously characterized as "a valley of ashes" in F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby.[42] Fitzgerald meanwhile described the Flushing River, now polluted from the dumps, as "a small foul river".[43] The dumps and garbage trains were accused of facilitating a polio outbreak in Corona in 1916.[44] The Brooklyn Ash Removal Company was brought to court by local residents in 1923 for "violation of the sanitary code" due to the smoke emitted from the dumps.[45][46] As a minor concession, the company opened the Corona Park Golf and Country Club in 1931, on a tract near Nassau Boulevard (today's Long Island Expressway).[43][47]

1939/1940 Fair and aftermath

New York City Parks Commissioner Robert Moses first conceived the idea of developing a large park in Flushing Meadow in the 1920s.[48] At the time, he envisioned the site to become a "true 'Central Park'", especially with much of city population moving to Queens and Long Island due to urban sprawl. Moses also planned Flushing Meadows to be the westernmost of a chain of parks running across Queens, which would include Kissena Park, Cunningham Park, Alley Pond Park, and Douglaston Park.[49][50] In 1929, representatives from surrounding communities created a plan to turn the ash dump into a recreational complex, and presented them to Queens Borough President George U. Harvey.[51]

In 1930, Moses released plans for numerous parks and highways in the city. This included the Grand Central Parkway, the construction of which would require taking land from the ash dumps. One of the provisional projects listed was a "Flushing River Park", along with a "Flushing River Parkway".[31][52] The Brooklyn Ash Removal Company's contract with the city expired in 1933,[53][54] and the city took over the company's assets and operations on May 25, 1934.[55][56][57] The Brooklyn Ash property occupied around 300 acres (120 ha) of the 1,000-acre (400 ha) site, north of what is now the Long Island Expressway.[58] The remainder of the meadows still contained natural wildlife. It was frequented by fur trappers, local residents collecting firewood and growing vegetables, and later, squatters during the Great Depression.[59] Areas of the dumps were also used for growing vegetables, with the soil fertilized by the garbage and manure.[60]

In 1935, the site, now planned as "Flushing Meadow Park", was selected for what would become the 1939 World's Fair.[61] In addition to the ash dumps and undeveloped meadows, houses in Corona east of 111th Street, adjacent to the dumps, were condemned and added to the site, displacing residents.[62][63] The plans were drafted by Parks Department landscape architect Gilmore David Clarke and his partner Michael Rapuano, designed in Beaux-Arts style.[64][65] Work on the World's Fair site began on June 16, 1936.[35] The project primarily involved leveling the ash mounds, with the leftover material used to fill other areas of the meadow. Two sites were excavated to create Meadow and Willow Lake, while much of the Flushing River was diverted into underground culverts. A floodgate was built to prevent tidal flow from flooding the lakes.[66][67] In addition to recreation, the lakes would serve as repositories for excess storm runoff.[68] The dirt from the lake sites was used as additional topsoil for the park.[69] The project was an around-the-clock job, with 450 workers operating on three daily shifts.[70][35][71][72] Workers had to combat the effects of high tide, and dust storms created by the ash. The work significantly changed the topography of the meadows, differing from that created by glaciation. Thousands of trees were transplanted to the fair site in order to create a natural landscape. Meanwhile, thousands of 100-foot (30 m) Douglas fir timbers were driven into the ground to act as pilings for the foundations of the fair structures.[73] The pedestrian plan called for numerous wide tree-lined pathways, including a central "Cascade Mall" leading to the Trylon and Perisphere, many of which would be retained for the park.[69]

Faced with having to dispose of the mountains of ashes, Moses incorporated a significant portion of the refuse into the bases of several roadways that bordered or bisected the park.[74] This included the Van Wyck Expressway (Interstate 678) running along the eastern side of the park, the nearby Interboro Parkway (now Jackie Robinson Parkway), and the Long Island Expressway (Interstate 495) that divides the park into north and south halves. The Grand Central Parkway separates a western lobe from the main part of the northern half, while the east-west Jewel Avenue bisects the southern half.[75] The success of the Flushing Meadows site as a garbage dump-turned-park led Moses and the city to develop other wetlands in the city into parks via short-term refuse landfilling. This process was used to create Marine Park and Spring Creek Park in Brooklyn, and Ferry Point Park in the Bronx. This was also the original plan for the Fresh Kills and Edgemere landfills, which remained open past their expected tenure and became large and long-term municipal waste sites.[74][76] The Fresh Kills site is currently being developed into Freshkills Park.[77]

_(16639606536).jpg.webp)

_(16458228567).jpg.webp)

In November 1939, a water main running through Flushing Meadows Park to supply water to Flushing failed. Unlike the fair buildings, the pipeline was not built on piling foundations and eventually sank into the marsh and landfill. In January 1940, Borough President Harvey demanded an investigation into the main's construction take place, while the Board of Estimate allocated $50,200 for repairs.[78] Following the closure of the Fair in 1940, the site was supposed to be cleared in order to develop and open Flushing Meadows as a city park. The onset of World War II, however, delayed the project.[79][80] The profits from the World's Fair were supposed to pay for the development of the park, but in spite of its success the fair turned a financial loss.[81] Only two permanent attractions were opened in 1941: an ice skating rink and roller rink[82][83] in the New York City Building,[84] and a public pool located in the New York State Marine Amphitheatre (now demolished).[85] The latter utilized the pool used for Billy Rose's Aquacade during the fair.[86]

In the meantime, some of the buildings from the 1939 Fair were used for the first temporary headquarters of the United Nations beginning in 1946. The former New York City Building was used for the UN General Assembly during this time.[87][88][84] Moses attempted to sell Flushing Meadows as a permanent headquarters for the UN, which would have required new structures and a complete redesign of the fair ground layout. The proposal was rejected however, due to concerns over the strength of the former marshland for building construction, the lack of "scenic beauty" in the meadows, and the distance from Manhattan. The UN moved to their now-permanent headquarters in 1951.[89] The New York City building was later refurbished for the 1964/1965 Fair as the New York City Pavilion, featuring the Panorama of the City of New York, an enormous scale model of the entire city.[90][84][91] It is one of two buildings that survive from the 1939/40 Fair, and the only one that remains in its original location.[92] (The other is the Belgium exhibition building, disassembled and moved to the campus of Virginia Union University in 1941.[93]) It is now the home of the Queens Museum of Art, which still houses, and occasionally updates, the Panorama.[84] The remainder of the park, meanwhile, had fallen into disrepair, with wild animals moving back into the area.[88] Only minor upgrades to the park occurred during this time.[94]

1964/1965 Fair

The Flushing Meadows site was selected in 1959 for the 1964 World's Fair.[95] Gilmore D. Clarke and Michael Rapuano were retained to tailor the original 1939 park layout for the new fair.[96] Three structures were retained from the 1939 Fair. Meanwhile, several new structures and attractions were created including the Unisphere, Shea Stadium, the New York Hall of Science, and Queens Botanical Garden; the latter three were intended as permanent attractions for the future park.[97] The Unisphere, built as the theme symbol for the 1964/1965 World's Fair, has since become the main sculptural feature of the park.[98] It stands on the site occupied by the Perisphere during the earlier Fair.[99] The Van Wyck Expressway was extended north through the park site along the right-of-way of the former World's Fair Railroad.[100] Moses and the Parks Department also prepared post-fair plans to finish Flushing Meadows Park, as well as Kissena Corridor Park and Kissena Park, projected to be complete by 1967.[101]

In early 1964, the New York City Council added "Corona" to the park's name; the park was now named "Flushing Meadows–Corona Park", in preparation for that year's World's Fair. Councilman Edward Sadowsky explained that this was intended to correct an injustice: "The people of Corona have long lived in the aroma of a junkyard or a dump named for their community. Now, when there is something beautiful to be seen, there is no mention of the name Corona."[3] Following the fair, most of the remaining $11.6 million from the fair funds, as well as money from Moses' Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority, were used to rehabilitate the site into a true park.[102] Flushing Meadows–Corona Park was transferred from the World's Fair Corporation back to the Parks Department, and opened on June 3, 1967.[50]

Late 20th century

Although the park was opened, it had yet to become the grand park Moses had originally envisioned.[103] In August 1967, new parks commissioner August Heckscher II sought to begin improvements on the park in order to turn it into the "Central Park of the 20th century." A new plan for the park had been designed by architects Marcel Breuer and Kenzō Tange, but the project did not receive funds due to communication issues with the New York City Comptroller's office.[104][105] By 1972, little development had taken place to improve the park, while many World's Fair structures remained in disrepair.[106][107] The disrepair was systematic within the park system, a product of lack of funding during that decade's fiscal crisis.[108] This state of disrepair continued into the 1980s.[109]

In 1975, a group of traditionalist Catholics started to assemble at the old Vatican Pavilion exedra monument of the 1964 New York World's Fair to have evening rosary prayer vigils, having been obligated to relocate from Bayside, Queens. This was led by a woman named Veronica Lueken who claimed she was experiencing visions there of the Virgin Mary, and giving out supposed messages from heaven, frequently apocalyptic in nature.[110][111] At its height in the late 20th century, thousands of people attended the nightly events, held on different feast days.[111] One event in June 1983 attracted fifteen thousand pilgrims.[110] Despite the events' popularity, Bishop Francis Mugavero, then Bishop of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Brooklyn, stated in a 1986 "Declaration Concerning the Bayside Movement" that the events lacked credibility.[112][113] After Lueken's death in 1995, and her husband's death in 2002, their followers divided into two small camps that continued to visit the park for vigils.[111][113]

Additionally, in 1978, the US Open tennis tournament was moved from the West Side Tennis Club in Forest Hills to Flushing Meadows Corona Park. The tournament was originally held in the Singer Bowl stadium (renamed the Louis Armstrong Stadium), a 1964 World's Fair structure which was renovated and expanded for the tournament. Other parts of the park were also repaired or expanded for the tournament, including the fountains of the Unisphere.[107][114]

Arne Abramowitz became administrator of Flushing Meadows–Corona Park in 1986 and soon began planning a renovation of the park.[115] The following year, NYC Parks announced an $80 million rehabilitation of the park.[116][117] The renovation had been planned since the early 1980s but had been deferred due to a lack of funding.[118] The grounds of the park's northern section were landscaped in 1992,[119] and the restoration of the Unisphere was completed in May 1994.[120][121] Since the early 1990s, the New York State Pavilion's ledges, steps, and fountain grates have been utilized by skateboarders and featured in famous east coast skateboarding videos.[122][123][124]

Early 21st century

By the early 2000s, the park had become the residence of a number of homeless people.[125] This fact received attention after five possibly homeless individuals abducted, raped, and threatened to kill a woman who had been sitting with her partner at the nearby Mets–Willets Point subway station.[126]

Several improvements were made to Flushing Meadows–Corona Park in the 2000s and 2010s. The Flushing Meadows–Corona Park Conservancy was formed in 2002 to advocate for parkland in the area.[127] The $66.3 million Flushing Meadows Natatorium, encompassing an Olympic-sized public indoor pool and an NHL regulation-sized skating rink, opened in 2008. The facility is the largest recreation complex in any New York City park, at 110,000 square feet (10,000 m2).[128] This was followed by the opening of Citi Field, a new baseball field to replace Shea Stadium, in 2009.[129]

Another public-private partnership, the Alliance for Flushing Meadows–Corona Park, was created in 2015.[130] It commenced construction on, or announced plans for, several improvement projects at Flushing Meadows–Corona Park.[131] These included a plan to restore the New York State Pavilion,[132][133] as well as the construction of a "mist garden" in the park's Fountains of the Fairs.[134][135][131] Other projects included the construction of a promenade around Meadow Lake[131][134][136] and the rehabilitation of the World's Fair Playground and the marina.[131] In 2015, Flushing Meadows–Corona Park also started hosting the Queens Night Market, a summertime food market that features cuisine from dozens of countries.[137] The market became popular due to its affordability, since all food cost a maximum of $5–6.[138][139] Another food festival, the World's Fare, started in 2017 and is hosted in Citi Field's parking lot on about the third weekend of May.[140][141] Restoration of the New York State Pavilion began in 2019,[142] as did work on the Fountains of the Fairs.[143] The Fountains of the Fairs were dedicated in October 2020.[144][145]

In early 2022, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) gave a local group, the Waterfront Alliance, a $530,000 grant to study the effects of climate change at Flushing Meadows–Corona Park after U.S. representative Grace Meng had requested the grant the previous year.[146][147] The park was extremely vulnerable to flooding because of its topography and because of sea level rise caused by global warming. Climate scientists had predicted that parts of the park would be flooded regularly by the 2050s[147] and that the entire park could be underwater by the 2080s.[146][148] At the time, the city government was spending $350 million on various upgrades at the park.[147] By mid-2023, the New York City government was considering erecting tents in Flushing Meadows–Corona Park to temporarily house asylum seekers. This move came after the federal government repealed an order authorizing Title 42 expulsions of migrants, which had been implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic.[149][150]

Description

Attractions and geographical features of Flushing Meadows–Corona Park:

Layout

The layout of Flushing Meadows–Corona Park retains much of Gilmore D. Clarke and Michael Rapuano's Beaux-Arts planning from the 1939 and 1964 World's Fairs.[151][152] The northern section of the park, the former fair grounds,[69] revolves around large paved pathways which during the fairs led to focal points such as pavilions, fountains and sculptures. The Trylon and Perisphere, and later Unisphere, were placed at the main axial point.[65][152][153] The Unisphere and Queens Museum currently sit at the west end of the main promenade. Near the center of the promenade (called Herbert Hoover Promenade on the north side, and Dwight D. Eisenhower Promenade on the south side) are the Fountains of the Fairs, which sit in the median of the paths. At the far east end is the Fountain of the Planets, originally called the Pool of Industry.[153] This layout was used to guide fair goers to exhibits.[154] The layout was based on Gian Lorenzo Bernini's plan for St. Peter's Square in Vatican City.[65][155] The main promenade, measuring 2,500 feet (760 m),[156] was provisionally called the "Cascade Mall" during its construction,[69] and later named the "Constitution Mall" during the first fair.[156] Many former exhibit and pavilion sites have since been replaced with soccer fields (artificial turf or dirt and grass), while others have been left as open grass fields.[157]

The southern portion of the park is largely occupied by Meadow and Willow Lake.[158] The two lakes, along with the Pool of Industry/Fountain of the Planets in the former fair grounds, are fed by the Flushing River, which flows north through both lakes and underneath the fountain as a subterranean river towards Flushing Bay.[159] The two lakes are connected by a narrow channel, forming a peninsula in between the lakes.[152] During the 1939 Fair, Meadow Lake was temporarily named "Fountain Lake" and "Liberty Lake".[160][161] The land around Meadow Lake contains much of the park's true "parkland", with open grass, picnic and grilling areas, and baseball and cricket fields.[162] During the fairs, the land on the north shore and part of the eastern shore of the lake was used as an amusement area,[163][63] with large parking lots added on the east and west shores for the 1964 Fair.[164][63][165] The lots were removed and converted to parkland after the 1964 Fair.[165] The Willow Lake area of the park is a nature reserve.[166] The area around Willow Lake originally also contained sports fields and park trails,[63][69][167] until it was fenced off and turned into a preserve in 1976.[63]

The park is entirely circumscribed by highways constructed by Robert Moses. Its eastern boundary is formed by the Van Wyck Expressway (I-678). The south and west ends of the park are bound by the Grand Central Parkway, with the Kew Gardens Interchange situated at the southernmost point. The northern edge of the park is bound by the expressway portion of Northern Boulevard (New York State Route 25A) which connects the Grand Central and the Whitestone Expressway. The park is bisected by the Long Island Expressway, at the approximate south end of the former Corona Ash Dumps, which separate the northern and southern halves of the park. Jewel Avenue and its interchange with the Grand Central further separate the southern section into two halves, with Meadow Lake to the north of Jewel Avenue and Willow Lake to the south.[75] Access to the park is limited due to a lack of public transportation reaching many areas of the site, and presence of the highways at the perimeters of the park separating the site from local neighborhoods. The park also has very few formal entrances from local neighborhoods; this is a vestige of the World's Fairs, where access was controlled.[168][109]

Studies by various groups have separated the park into a different number of sections. A study by the Columbia Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation divides the park into three areas: the "historic core" (former World's Fair grounds), Meadow Lake, and Willow Lake.[169] The Flushing Meadows Corona Park Strategic Framework Plan divides the park into a total of seven "zones": the Marina along Flushing Bay (containing the World's Fair Marina), the "Sport Center" (containing Citi Field and the USTA), "West Park" (a small section extending west of the Grand Central Parkway and the fair grounds, housing the New York Hall of Science and the Queens Zoo), the "Recreation & Garden Botanical Area" (extending east of the fair grounds along the Kissena Creek corridor, housing the Queens Botanical Garden), the "Historic World's Fair Core Area", Meadow Lake, and Willow Lake.[166]

Size

Flushing Meadows–Corona Park is the fourth-largest public park in New York City. It was long believed to be 1,255 acres (508 ha) in size, but a survey concluded in 2013 found its actual size to be 897 acres (363 ha) when accounting for major roads and other exclusions within the park's perimeter.[170] This does not take into account a disputed claim that the neighborhood of Willets Point, along the north edge of the park, is itself part of the park.[171]

Ecology

_09.jpg.webp)

The two lakes and the remainder of Flushing Creek are separated by a flood gate or dam called the "Porpoise Bridge" or "Tide Gate Bridge", located just south of the Long Island Rail Road's Port Washington Branch trestle, at the north end of the Flushing Meadows Golf Center. The dam only permits northward flows towards Flushing Bay to pass, while blocking south-flowing waters.[95][63] As its name implies, the dam also acts as a bridge, carrying pedestrian and vehicular traffic over the creek. It measures 37 feet (11 m) wide and 370 feet (110 m) long.[172] The lakes are fed by groundwater.[173][63]

Prior to human development, Flushing Meadows was originally a tidal marsh, with Flushing Creek receiving south-flowing waters from the tides of Flushing Bay. Although the lakes were built as freshwater lakes and dammed to mitigate tidal effects, flooding continues to affect the park.[174][67] The lakes are also highly eutrophic, due to nutrients such as phosphorus from the former marshland seeping into the water, leading to the death of fish in the lakes. The regular tidal action that would filter the lakes is prevented by the dam.[175] In addition, the lakes are subject to pollution and storm runoff from the nearby highways, via pipes which feed into the lakes.[176][67]

Because of its connection with Flushing Bay, several fish species native to marine habitats regularly swim into and inhabit Meadow and Willow Lakes.[177] Fish species native to Meadow Lake include American eel, largemouth bass, northern snakehead (an invasive species), and white mullet.[177] Willow Lake is named for the many species of willow plants which inhabit the area.[178] Invasive phragmites, a genus of wild grasses, are also abundant.[179][178][167] Attempts to kill the phragmites with pesticides have led to further fish kill.[167][180] Numerous berry-producing trees and shrubs near Willow Lake attract several migratory bird species.[178] The biodiversity of the lakes has been found to be much lower than other water bodies of comparable size.[179]

Attractions

Near the northern end of the park, adjacent to Willets Point is the "Sport Center" zone, where the US Open tennis tournament is held.[181] In 2006, the tennis center was named USTA Billie Jean King National Tennis Center after professional tennis player Billie Jean King.[182] Its center court is Arthur Ashe Stadium, and its secondary stadium court is Louis Armstrong Stadium.[183] Citi Field, the home of the New York Mets since 2009, sits at the far north end of the park. Shea Stadium, the Mets' previous home and prior host to the New York Jets football team, once stood adjacent to the area now hosting Citi Field.[181]

In addition to the existing stadiums, several other sports venues have been proposed for the park. In the 1950s, Flushing Meadows was one of several proposed sites for the relocation of the Brooklyn Dodgers, until the franchise moved to Los Angeles in 1958.[184] A racing circuit to host a Formula One grand prix event was proposed for New York City, with one of the potential circuits to be built around Meadow Lake, first for the 1975 season, and later for the 1983 season.[185][186][187] The plans were opposed by the local community and environmental groups, and the race was postponed and ultimately canceled by 1985.[169][188][189] One of the alternate sites, the Meadowlands Sports Complex in New Jersey, would host the Meadowlands Grand Prix Champ Car event in 1984.[190] Also in the 1980s, the New Jersey Generals of the United States Football League (USFL) proposed to relocate to the park, with a new stadium to be built in Willets Point adjacent to Shea Stadium. The plans dissolved when the USFL folded in 1985.[191][192] Shortly afterwards, the New York Jets rejected a plan to take over the proposed stadium.[193][194] In the 2010s, a Major League Soccer stadium was proposed in the park after MLS founded New York City FC, the New York area's second soccer team. After examining several sites in the New York area, New York City FC finally decided on building its proposed stadium in Flushing Meadows–Corona Park by 2016, deeming the park as the only viable location for a stadium.[195] The stadium, which would have been located on the site of the Pool of Industry/Fountain of the Planets,[196] was heavily opposed by the community,[197] which forced the team to change its plans and play at Yankee Stadium.[198] In November 2022, New York City and NYCFC agreed to build the soccer club's 25,000-seat stadium in Willets Point adjacent to Citi Field; it is expected to be completed in 2027.[199][200]

The park's Meadow Lake contains a boat house, one of two structures that remain from the 1939 World's Fair, the other being the Queens Museum.[201] Rental boats are available at the boathouse for rowing and paddleboating, and Meadow Lake is also the site of rowing activities for non-profit Row New York, with teams practicing on the lake for much of the year.[202] Meadow Lake also hosts the annual Hong Kong Dragon Boat Festival in New York, and teams from New York practice in Meadow Lake during the summer months. The American Small Craft Association[203] (TASCA) also houses a fleet of over a dozen 14.5-foot (4.4 m) sloop-rigged sailboats, used for teaching, racing, and recreation by the club's members. Bicycling paths extend around Meadow Lake and connect to the Brooklyn–Queens Greenway.[204] The Willow Lake Trail, a nature trail around Willow Lake,[205] was partially reopened in 2013 and is part of the Willow Lake nature preserve. The 78th Avenue gate to the lake remains shuttered and inaccessible despite being the closest gate to the Kew Gardens–Union Turnpike subway station.[206][207] The chronic lack of maintenance of this portion of the trail has led to ordinary residents to resort to clearing the trail itself.[208] The many recreational playing fields and playgrounds in the park are used for activities that reflect the wide ethnic mix of Queens; soccer and cricket are especially popular.[209] New York Road Runners also hosts a weekly 3.30-mile (5.31 km) Open Run.[210] as well as an annual 6.2-mile (10.0 km) 10K run.[211]

Some World's Fair buildings continued to be in use after the 1964 Fair. The Flushing Meadows Carousel, opened as part of the 1964 Fair, operates in the northwestern part of the park.[212] The New York Hall of Science, founded during the 1964 World's Fair, was one of the country's first science museums and still operates in its original location at the park's northern corner.[213] The New York State Pavilion, constructed as the state's exhibit hall for the same World's Fair, is also a feature of the park. However, no new use for the building was found after the Fair, and the structure sits derelict and decaying,[214][215] although it was repainted yellow in 2015.[216][215] Next to the New York State Pavilion is the Queens Theatre in the Park,[217] originally the 1964 Fair's "Theaterama" attraction,[218] which moved into its current building in 1993.[217] Terrace on the Park, a banquet and catering facility, was originally the 1964 World's Fair's official helipad.[219] The Queens Museum, which became the headquarters of the United Nations General Assembly after the 1939 Fair, was adapted as the 1964 Fair's New York City Pavilion building. After the fair, it was subdivided into the Queens Center for Art and an ice-skating rink, the latter of which was removed when the museum was expanded in 2013.[220]

Other buildings remained for a while after the 1964 Fair's conclusion to see if a new use for them could be found, but were subsequently demolished. This included the Travel and Transportation Pavilion, destroyed in 1967 after a failed conversion to a fire station, and the Federal Pavilion, demolished in 1977 after great deterioration.[221] One such parcel became the site of the Playground for All Children, one of the first playgrounds designed to include handicapped-accessible activities. The design competition for the playground was won by architect Hisham N. Ashkouri; the facility was completed in 1984, and it was refurbished and reopened in 1997.[222]

Art installations

Immediately outside the USTA Billie Jean King National Tennis Center is a sculpture by Eric Fischl called Soul in Flight.[223][224] The sculpture, unveiled in August 2000, is a 14-foot bronze nude statue that serves as a permanent memorial to Arthur Ashe and includes one of his favorite quotes, "From what we get we can make a living; what we give, however, makes a life."[225]

In January 2022, sculptor Sherwin Banfield unveiled Going Back to the Meadows, a statue of Queens-born LL Cool J. Located in David Dinkins Circle, the installation depicts him in a Kangol bucket hat and Cuban link chain, holding up a solar-powered boombox loaded with a cassette of his 1985 debut album, Radio.[226][227] The sculpture, which is planned to remain through November 2022, features speakers that are timed to play LL Cool J's music for five hours on several days of the week.[228]

Other infrastructure

This park also contains three Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) maintenance facilities: the Jamaica subway yard, the Corona subway yard, and the Casey Stengel Bus Depot. The Jamaica Yard is located at the very south end of the park site, beyond Willow Lake, while the Corona Yard and Casey Stengel Depot are located across from Citi Field.[183]

Transportation

The New York City Subway and Long Island Rail Road both serve the park's northern end. The IRT Flushing Line subway station at Mets–Willets Point serves the 7 and <7> trains, and the similarly named LIRR station serves the Port Washington Branch. These stations are located at the northern end of the park adjacent to the Corona Yard and bus depot, primarily serving Citi Field and the USTA.[229][230] The 111th Street subway station is located just outside the park grounds, serving the Hall of Science.[229] The Q48, Q58, Q64 and Q88 buses all travel through the park, but only the Q48 stops within the park perimeter, serving Citi Field and the USTA. The Q58 and Q88 stop outside either side of the park and cross the park via the Horace Harding Expressway, while the Q64 crosses the park along Jewel Avenue/69th Road.[231][232]

In media

The "Valley of Ashes" described in F. Scott Fitzgerald's novel The Great Gatsby (1925) is a fictional location said to have been inspired by the site of Flushing Meadows–Corona Park when it was still a dump, as well as by nearby Willets Point.[233]

In the movie Men in Black (1997), the saucer-shaped restaurants atop the observation towers of the New York State Pavilion were portrayed as real alien UFOs used as a display to disguise its appearance to the public. Edgar the bug attempts to use one to escape Earth, but not before being shot down by the agents (destroying the Unisphere in the process), after which it attempts to climb aboard the second ship but is stopped by Jay, who tricks it into coming back down.[215][234] Scenes for the film Men in Black 3 (2012) were also filmed at Flushing Meadows.[234] That film features a scene that recreates Shea Stadium, demolished in 2009, during the 1969 World Series.[235]

The intro to the long-running 1990s sitcom The King of Queens was partly shot in Flushing Meadows–Corona Park.[236] In 2001, during the first season of The Amazing Race, the Unisphere at Flushing Meadows Park served as the Finish Line. In 2014, it served as a stop on the first leg of Season 25.[237]

In the Marvel Cinematic Universe, the Stark Expo—first featured in Iron Man 2 (2010)—takes place at the Flushing Meadows–Corona Park and appears in multiple films in the series, including Captain America: The First Avenger (2011) and briefly in Spider-Man: Homecoming (2017).[238][239][240]

In early 2018, musician Paul Simon announced that he would perform his final live concert at Flushing Meadows–Corona Park on September 22, 2018. Simon had grown up near the neighborhood and had visited the park frequently.[241][242]

References

Citations

- Queens Community Boards Archived February 2, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, New York City. Retrieved September 3, 2007.

- Steinberg 2015, p. 220.

- "Bill Adds 'Corona' to Fair Site's Name". The New York Times. February 5, 1964. Archived from the original on November 13, 2017. Retrieved January 29, 2012.

- Strategic Framework Plan, p. 52; Stage 1A Assessment, p. 2; Phase 1A Report 1985, p. 3; Mankiewicz & Mankiewicz 2002, p. 31.

- Mankiewicz & Mankiewicz 2002, p. 32.

- Stage 1A Assessment, p. 2.

- Feller, Michael (December 1988). "Kissena Park: The Wild Side; A Guide to its Natural Areas" (PDF). New York City Department of Parks and Recreation, Natural Resources Group. p. 2−4. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved June 2, 2018.

- Strategic Framework Plan, p. 52.

- Stage 1A Assessment, p. 7.

- "Flushing Meadows Corona Park: History". New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. Archived from the original on May 7, 2021. Retrieved March 28, 2017.

- Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. (1995). The Encyclopedia of New York City. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 462. ISBN 0300055366.

- Stage 1A Assessment, p. 5.

- Natural Resources Group. "Natural Area Mapping and Inventory of Spring Creek 1988 Survey" (PDF). New York City Parks Department. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved November 18, 2015.

- Stage 1A Assessment, p. 8.

- "Flushing Meadows Corona Park: World's Fair Marina". New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. Archived from the original on April 7, 2021. Retrieved March 28, 2017.

- Stage 1A Assessment, pp. 8–9.

- Stage 1A Assessment, p. 9.

- Stage 1A Assessment, p. 10; Phase 1A Report 1985, p. 18.

- Strategic Framework Plan, p. 52; Steinberg 2015, p. 211.

- Vincent F. Seyfried (1986). Corona: From Farmland to City Suburb, 1650–1935. publisher not identified. pp. 66–70. Retrieved April 8, 2017.

- Stage 1A Assessment, p. 11.

- Steinberg 2015, p. 211; Stage 1A Assessment, p. 11; PANYNJ Airport Transit Environmental Impact Statement 1994, p. 1⋅10.

- Phase 1A Report 1985, p. 18.

- "Paragraphs of Interest" (PDF). Newtown Register. September 28, 1911. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved March 27, 2017 – via Old Fulton New York Postcards.

The announcement made this week that the contractors who have filled in the Flushing meadows intend to develop the water front ...

- Steinberg 2015, p. 211; Strategic Framework Plan, p. 52; Stage 1A Assessment, p. 11; Phase 1A Report 1985, p. 19; PANYNJ Airport Transit Environmental Impact Statement 1994, p. 1⋅10.

- Schneider, Daniel B. (November 28, 1999). "F.Y.I." The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 8, 2022. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

- Stage 1A Assessment, p. 11; Steinberg 2015, p. 212.

- Stage 1A Assessment, p. 13; Phase 1A Report 1985, p. 23; PANYNJ Airport Transit Environmental Impact Statement 1994, p. 1⋅10.

- PANYNJ Airport Transit Environmental Impact Statement 1994, p. 1⋅10.

- Stage 1A Assessment, p. 14; Phase 1A Report 1985, p. 26; PANYNJ Airport Transit Environmental Impact Statement 1994, p. 1⋅10.

- Steinberg 2015, p. 213.

- Steinberg 2015, p. 212; PANYNJ Airport Transit Environmental Impact Statement 1994, p. 1⋅10.

- PANYNJ Airport Transit Environmental Impact Statement 1994, p. 1⋅10; Willets Point DEIS 2013, p. 1⋅3.

- NYC Parks Tomorrow's World 2015; Steinberg 2015, p. 212; Strategic Framework Plan, p. 52.

- "Work at Fair Site Begins Without Ceremony; 700 Job-Seekers on Hand, 500 to Be Hired". The New York Times. June 16, 1936. Archived from the original on November 23, 2017. Retrieved March 27, 2017.

- Willets Point DEIS 2013, p. 1⋅3.

- Steinberg 2015, p. 213; Strategic Framework Plan, p. 52; Stage 1A Assessment, pp. 14–15; Willets Point DEIS 2013, p. 1⋅3.

- "WAR DECLARED UPON RATS.; Extermination of Pests in Corona and Elmhurst Ordered by Copeland". The New York Times. November 4, 1920. Archived from the original on November 22, 2017. Retrieved March 27, 2017.

- Stage 1A Assessment, p. 12; Phase 1A Report 1985, p. 21.

- Steinberg 2015, p. 217; Willets Point DEIS 2013, p. 1⋅3.

- "Health Department Wars on Mosquitos; Great Number of Pests Laid to Heavy Rains". The New York Times. August 20, 1925. Archived from the original on June 16, 2018. Retrieved March 27, 2017.

- Stage 1A Assessment, pp. 14–15; Strategic Framework Plan, p. 52.

- NYC Parks Tomorrow's World 2015, p. 5.

- Phase 1A Report 1985, p. 24.

- "Smoke Nuisance Charge: Case Against Brooklyn Ash Removal Company Is Adjourned" (PDF). The New York Times. September 14, 1923. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved March 27, 2017.

- "Ash Company Held on Nuisance Charge: Special Sessions Court to Act on Maintenance of Corona Meadows Smudge" (PDF). Brooklyn Standard Union. September 26, 1923. p. 14. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved March 27, 2017 – via Old Fulton New York Postcards.

- "PLAN GOLF COURSES IN CORONA MEADOWS; Brooklyn Owners to Convert Land Into a Sport Centre". The New York Times. July 22, 1929. Archived from the original on June 16, 2018. Retrieved March 27, 2017.

- Caro 1974, p. 1083.

- 30 Years of Progress: 1934–1965, p. 56; PANYNJ Airport Transit Environmental Impact Statement 1994, p. 1⋅11.

- Schumach, Murray (June 4, 1967). "MOSES GIVES CITY FAIR SITE AS PARK; Flushing Meadows in Queens Becomes the 2d Biggest Recreation Area Here". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 22, 2017. Retrieved March 28, 2017.

- "Harvey Asked to Make Park Out Of Dump: Community Councils Suggest Development of Wasteland" (PDF). Long Island Daily Press. September 11, 1929. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved March 27, 2017 – via Old Fulton New York Postcards.

- "ASKS NEW CITY PARKS TO COST $20,000,000; Metropolitan Conference Urges Prompt Purchases, Chiefly in Queens and Richmond. BERRY GETS HONOR SCROLL Calls for a 'Normal' Pace in Public Projects and Predicts Agency to Coordinate Them". The New York Times. February 26, 1930. Archived from the original on November 22, 2015. Retrieved November 19, 2015.

- "City Ash Removal Halted by Court; Brooklyn Company Gets Stay to Prevent Municipality Operating Its Plants". The New York Times. December 30, 1933. Archived from the original on July 25, 2018. Retrieved March 27, 2017.

- "CITY NOW REMOVING ASHES IN BROOKLYN; Company's Agreement to Drop Suit Speeds Municipal Operation of Three Plants". The New York Times. January 9, 1934. Archived from the original on July 25, 2018. Retrieved March 27, 2017.

- "Flushing Meadows Corona Park: Lawrence Playground". New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. Archived from the original on March 30, 2017. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- Soper, George R. (March 18, 1934). "DISPOSAL OF WASTE AN URGENT PROBLEM; Supreme Court Order Against Dumping at Sea Points the Need for Incinerators READY FOR DUMPING". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 28, 2017. Retrieved March 27, 2017.

- "ASH COMPANY VALUE UNDER CITY INQUIRY; Proposed Purchase of Brooklyn Concern Brings Charge of $1,000,000 'Hijacking' Plan". The New York Times. February 10, 1934. Archived from the original on July 25, 2018. Retrieved March 27, 2017.

- Historic Preservation Studio 2015, p. 7; Steinberg 2015, p. 213.

- Steinberg 2015, p. 217.

- Phase 1A Report 1985, p. 22.

- "Great World Fair for City in 1939 on Site In Queens;...City to Lend New Park". The New York Times. September 23, 1935. Archived from the original on April 7, 2021. Retrieved January 29, 2012.

- Historic Preservation Studio 2015, p. 8; Steinberg 2015, p. 218.

- Kadinsky, Sergey (2016). Hidden Waters of New York City: A History and Guide to 101 Forgotten Lakes, Ponds, Creeks, and Streams in the Five Boroughs. New York, NY: Countryman Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-1-58157-566-8.

- Unisphere 1995, p. 1.

- "Flushing Meadows Corona Park: Unisphere". New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. Archived from the original on December 1, 2021. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- Caro 1974, p. 1085; NYC Parks Tomorrow's World 2015, p. 5; Steinberg 2015, p. 213; Strategic Framework Plan, pp. 37, 52.

- Siegel, Sarah (2006). "Flushing the Meadows – relaxing a post-World's Fair urban landscape" (PDF). International Federation of Landscape Architects. p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- Mankiewicz & Mankiewicz 2002, p. 9.

- "VAST QUEENS PARK RISING ON FAIR SITE". The New York Times. December 6, 1936. Archived from the original on April 7, 2021. Retrieved April 4, 2017.

- NYC Parks Tomorrow's World 2015, p. 7.

- "'Cut and Fill' Grading of World's Fair Site Reported More than One-Third Complete". The New York Times. October 11, 1936. Archived from the original on March 28, 2017. Retrieved March 27, 2017.

- "Task of Filling World's Fair Site Will Be Pushed Night and Day; Moving of 7,000,000 Cubic Yards of Ashes and Soil Will Be in Full Swing Next Week – Two Lakes to Be Dug as Part of Work to Last till Next March". The New York Times. July 8, 1936. Archived from the original on July 25, 2018. Retrieved March 27, 2017.

- Steinberg 2015, p. 219.

- 30 Years of Progress: 1934–1965, p. 8; Steinberg 2015, p. 214.

- 30 Years of Progress: 1934–1965, p. 64; Historic Preservation Studio 2015, p. 126; Strategic Framework Plan, p. 14.

- Sullivan, Michael (January 4, 1962). "Garbage Dump Today, Park Tomorrow" (PDF). Long Island Star-Journal. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved January 7, 2017 – via Old Fulton New York Postcards.

- Steinberg 2015, p. 321.

- "Harvey Demands Probe of Sinking Fair Site Main; Water Pipe Laid in Mud, He Declares; Board Approves $50,200 Fund For Needed Repairs". Long Island Star-Journal. January 19, 1940. p. 9. Archived from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved August 8, 2018 – via Old Fulton New York Postcards.

- "Ready to Turn Fair Into Park; Moses Tells Mayor His Plans Are Set" (PDF). The Sun (New York). August 15, 1940. p. 14. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved March 27, 2017 – via Old Fulton New York Postcards.

- "Flushing Meadow" (PDF). Long Island Star-Journal. July 13, 1949. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved March 27, 2017 – via Old Fulton New York Postcards.

- Unisphere 1995, p. 3.

- "Moses Seeks $134,073 For Meadow Park Pay" (PDF). Long Island Star-Journal. February 15, 1941. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved April 26, 2017 – via Old Fulton New York Postcards.

- Markland, John (February 9, 1941). "Park Rising on Fair Site: New Skating Rinks Are First Development in a Vast Project". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 27, 2017. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- "Building History". Queens Museum. Archived from the original on April 26, 2015. Retrieved June 20, 2015.

- "Pool to be Opened on Aquacade Site". The New York Times. July 14, 1941. Archived from the original on July 25, 2018. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- Historic Preservation Studio 2015, p. 13; NYC Parks Tomorrow's World 2015, p. 29.

- Historic Preservation Studio 2015, pp. 14–15; Strategic Framework Plan, p. 53; PANYNJ Airport Transit Environmental Impact Statement 1994, p. 1⋅11.

- "FOUL LOT to FAIR: A SAGA by MOSES". The New York Times. April 11, 1966. Archived from the original on November 22, 2017. Retrieved March 27, 2017.

- Caro 1974, p. 1085; Historic Preservation Studio 2015, p. 21.; Mires, Charlene (April 8, 2015). Capital of the World: The Race to Host the United Nations. New York University Press. pp. 196, 199. ISBN 978-1-4798-3375-7. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- Historic Preservation Studio 2015, p. 24.

- The Panorama of the City of New York Archived March 12, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Queens Museum of Art. Retrieved May 16, 2012.

- Strategic Framework Plan, p. 53.

- Historic Preservation Studio 2015, p. 18.

- Historic Preservation Studio 2015, pp. 18–19.

- PANYNJ Airport Transit Environmental Impact Statement 1994, p. 1⋅11.

- Historic Preservation Studio 2015, p. 16; Unisphere 1995, p. 3.

- 30 Years of Progress: 1934–1965, p. 57; Strategic Framework Plan, p. 53.

- Strategic Framework Plan, p. 54; Unisphere 1995, p. 1.

- Unisphere 1995, pp. 1, 3.

- Mankiewicz & Mankiewicz 2002, p. 35.

- 30 Years of Progress: 1934–1965, p. 57; Moses, Robert (July 14, 1964). Flushing Meadow and Beyond; Post World's Fair Program; Progress Report (PDF). New York World's Fair 1964–1965 Corporation. p. 11. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- Caro 1974, p. 1085; PANYNJ Airport Transit Environmental Impact Statement 1994, p. 1⋅11; Unisphere 1995, p. 4.

- Caro 1974, pp. 1086–1087.

- Hoffman, Paul (August 28, 1967). "PARK IN FLUSHING GETS TOP PRIORITY; Heckscher Hopes to Make It the 'Park of the Century'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 7, 2021. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- Huxtable, Ada Louise (August 12, 1967). "Flushing Meadows Park Plan Delayed by Auditing; AUDITING DELAYS PARK IN FLUSHING". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 9, 2017. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- Weiss, Samuel (September 10, 1972). "Future of the Fair Site Still Debated". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 7, 2021. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- Shaman, Diana (December 3, 1978). "In Corona, They Look for a Lift From Tennis". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 26, 2021. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- Historic Preservation Studio 2015, p. 19.

- Coakley, Michael (August 24, 1984). "'64 Flushing Meadows fair site becomes $1 billion wasteland". Chicago Tribune. New York City. Archived from the original on March 30, 2017. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- Laycock, J.P. (2014). The Seer of Bayside: Veronica Lueken and the Struggle to Define Catholicism. Oxford University Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-19-937968-2. Archived from the original on October 1, 2022. Retrieved March 29, 2021.

- Kilgannon, Corey (October 9, 2003). "Visions of Doom Endure in Queens; Prophecy, and a Rift, at a Shrine". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 11, 2021. Retrieved March 29, 2021.

- Mugavero, Francis (November 4, 1986). "Declaration Concerning the 'Bayside Movement'". EWTN Global Catholic Television Network. Archived from the original on March 23, 2021. Retrieved March 29, 2021.

- "The Seer of Bayside". NYC Department of Records & Information Services. December 20, 2019. Archived from the original on March 4, 2021. Retrieved March 29, 2021.

- "U.S. Open Site Goes Public for '78". The New York Times. May 28, 1977. Archived from the original on July 26, 2021. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- Rivera, Elaine (December 30, 1986). "New Park Chief Building a Career in Open Spaces". Newsday. p. 21. Archived from the original on July 26, 2021. Retrieved July 26, 2021 – via newspapers.com

.

. - Anderson, Susan Heller (November 19, 1987). "Park in Queens to Get $80 Million Restoration". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 26, 2021. Retrieved July 26, 2021.

- Neugebauer, William (September 20, 1987). "It may be the jewel in city park crown". New York Daily News. pp. 318, 319. Archived from the original on July 26, 2021. Retrieved July 26, 2021 – via newspapers.com

.

. - Polsky, Carol (August 9, 1988). "Flushing Meadows Stuck in Park". Newsday. pp. 9, 24. Archived from the original on July 26, 2021. Retrieved July 26, 2021 – via newspapers.com

.

. - "Overdue facelift for park in works". Newsday. May 17, 1992. pp. 207, 216, 217. Archived from the original on July 26, 2021. Retrieved July 26, 2021 – via newspapers.com

.

. - Huang, Vivian (June 1, 1994). "Let us spray for Unisphere". New York Daily News. p. 293. Archived from the original on January 23, 2023. Retrieved November 4, 2019 – via newspapers.com

.

. - Muschamp, Herbert (September 2, 1994). "Summer's Last Hurrah: The Final Fling Before the Fall; Recircling the Globe". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 19, 2020. Retrieved November 4, 2019.

- Thrasher, Steven (May 18, 2010). "Maloof Money Brings NYC a Massive Skate Party, and a Free Park". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on April 19, 2017. Retrieved April 18, 2017.

- Fischler, Jacob (June 10, 2010). "Queens tweaks its wheels at first skate tourney". Queens Chronicle. Archived from the original on June 15, 2018. Retrieved April 18, 2017.

- Mehring, Jonathon. "Tribute to NYC street skating: Testing Out Flushing Meadows". X Games. Archived from the original on April 19, 2017. Retrieved April 19, 2017.

- Feuer, Alan (March 25, 2011). "Who Calls Central Park Home? Census Counts 25". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 7, 2021. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- Wilson, Michael (December 28, 2002). "Squalid Site of Queens Rape Unnoticed by Public Nearby". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 6, 2017. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- Miller, Shane (April 24, 2013). "Willow Lake trail named for the late Pat Dolan - A nature trail that winds around a lake in Flushing Meadows-Corona Park was renamed Sunday in honor of a woman who worked for years to preserve its natural beauty. On Sunday morning at a Kew Gardens..." Queens Ledger. Archived from the original on April 7, 2021. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- "Flushing Meadows Corona Park". New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. Archived from the original on November 26, 2011. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- Vecsey, George (March 29, 2009). "Ballpark Pioneers Witness Citi Field's First Pitch". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 7, 2021. Retrieved May 22, 2019.

- "New Alliance for Flushing Meadows-Corona Park Hopes to Boost Funds". DNAinfo New York. Archived from the original on December 1, 2018. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- "World's Fair fountains in Queens to get $5M makeover". am New York. February 12, 2018. Archived from the original on May 13, 2019. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- Haynes, Daniel C. (June 2, 2018). "FMCP projects win design awards". Queens Chronicle. Archived from the original on January 17, 2020. Retrieved June 2, 2018.

- "New York State Pavilion Observation Towers Reconstruction : NYC Parks". www.nycgovparks.org. Archived from the original on April 7, 2021. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- Plitt, Amy (February 13, 2018). "World's Fair fountains in Queens will transform into 'mist gardens'". Curbed NY. Archived from the original on July 26, 2021. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- "Flushing Meadows Corona Park Fountain of the Fairs Reconstruction : NYC Parks". www.nycgovparks.org. Archived from the original on May 13, 2019. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- "Flushing Meadows Corona Park Meadow Lake Promenade Reconstruction : NYC Parks". www.nycgovparks.org. Archived from the original on May 13, 2019. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- Gleason, Will (March 11, 2019). "Citing its diversity and culture, NYC was voted best city in the world in new global survey". TimeOut. Archived from the original on May 11, 2019. Retrieved June 23, 2019.

- Parry, Bill (April 18, 2019). "Queens International Night Market kicks off another season Saturday night". QNS.com. Archived from the original on May 25, 2019. Retrieved May 22, 2019.

- Passy, Charles (March 8, 2019). "Queens Night Market Begins a New Chapter". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on May 17, 2019. Retrieved May 22, 2019.

- Hallum, Mark (November 28, 2018). "The World's Fare returns to Flushing's Citi Field in May of 2019 for second helping of global eats". QNS.com. Archived from the original on May 25, 2019. Retrieved May 22, 2019.

- "'World's Fare' Returns To Queens For Weekend Of Global Cuisine". MSN. May 10, 2019. Archived from the original on December 31, 2019. Retrieved May 22, 2019.

- Parry, Bill (November 8, 2019). "NYC Parks breaks ground on $24 million project to preserve the World's Fair Pavilion towers". QNS.com. Archived from the original on August 15, 2020. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- "Flushing Meadows Corona Park Fountain of the Fairs Reconstruction". New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. Archived from the original on April 26, 2020. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- Parry, Bill (October 29, 2020). "City completes $6.8 million restoration of fountains at Flushing Meadows Corona Park". QNS.com. Archived from the original on June 25, 2021. Retrieved July 26, 2021.

- Weaver, Shaye (October 30, 2020). "See the new misting plaza at Flushing Meadows Corona Park". Time Out New York. Archived from the original on July 26, 2021. Retrieved July 26, 2021.

- "Flood-prone city park gets a climate resilience plan". Crain's New York Business. March 31, 2022. Archived from the original on October 31, 2022. Retrieved October 31, 2022.

- Feldman, Ari Ephraim (March 17, 2022). "Federal grant spurs Flushing Meadows Corona Park resiliency plan". Spectrum News NY1 New York City. Archived from the original on October 31, 2022. Retrieved October 31, 2022.

- Parry, Bill (April 1, 2022). "Waterfront Alliance secures federal funding for climate resilience plan for Flushing Meadows Corona Park – QNS.com". QNS.com. Archived from the original on October 31, 2022. Retrieved October 31, 2022.

- Rubinstein, Dana (May 8, 2023). "Racetracks, Parks, Offices: A Frantic Search for Migrant Housing". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 12, 2023. Retrieved May 12, 2023.

- Gloria Pazmino, Samantha Beech (May 6, 2023). "New York City mayor announces plan to transport willing migrants to locations outside the city ahead of expected surge". CNN. Archived from the original on May 12, 2023. Retrieved May 12, 2023.

- Historic Preservation Studio 2015, p. 71; Strategic Framework Plan, p. 17; Unisphere 1995, pp. 3–4.

- Dunlap, David W. (August 26, 2001). "A Queens Park's Past Shapes Its Future". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 26, 2021. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- Strategic Framework Plan, pp. 15, 18.

- Historic Preservation Studio 2015, p. 71; Strategic Framework Plan, pp. 15, 18, 21.

- NYC Parks Tomorrow's World 2015, p. 3.

- Wood 2004, p. 19.

- Historic Preservation Studio 2015, pp. 46–47.

- Historic Preservation Studio 2015, pp. 49–50; Strategic Framework Plan, pp. 15, 18, 21.

- Strategic Framework Plan, p. 37.

- Wood 2004, p. 13.

- Loeb, August (October 27, 1940). "Fine Park From Fair: Flushing Meadow's New Play Area Will Be 'Second to None'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 7, 2021. Retrieved April 27, 2017.

- Historic Preservation Studio 2015, p. 46; Strategic Framework Plan, p. 21.

- Cotter & Young 2014, p. 13; Wood 2004, p. 108.

- Cotter & Young 2014, p. 13.

- Alden, Robert (August 11, 1965). "A LEGACY OF FAIR: UNWANTED RELICS; Exhibitors Are Required to Raze Pavilions, but 13 Have Gone Bankrupt". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved April 27, 2017.

- Strategic Framework Plan, p. 21.

- Colangelo, Lisa L. (November 24, 2014). "Something is fishy in Flushing Meadows Corona Park's Willow Lake where scores of fish are dying". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on April 7, 2021. Retrieved April 27, 2017.

- Strategic Framework Plan, pp. 13, 39.

- Historic Preservation Studio 2015.

- Foderaro, Lisa W. (May 31, 2013). "How Big Is That Park? City Now Has the Answer". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 5, 2017. Retrieved May 31, 2013.

- Honan, Katie (February 11, 2014). "Suit Seeks to Quash Willets West Mall Project". DNA Info. Archived from the original on December 26, 2014. Retrieved December 25, 2014.

- "Request for Proposals: Porpoise Bridge" (PDF). New York City Department of Design and Construction. May 8, 2013. p. RFP 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- PANYNJ Airport Transit Environmental Impact Statement 1994, p. 1⋅11; Mankiewicz & Mankiewicz 2002, p. 19.

- Strategic Framework Plan, p. 43.

- Strategic Framework Plan, p. 37; Mankiewicz & Mankiewicz 2002, p. 1; PANYNJ Airport Transit Environmental Impact Statement 1994, p. 1⋅11.

- Strategic Framework Plan, p. 37; Mankiewicz & Mankiewicz 2002, p. 19; PANYNJ Airport Transit Environmental Impact Statement 1994, p. 1⋅11.

- "Meadow Lake". New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Archived from the original on November 18, 2021. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- "Flushing Meadows Corona Park: Willow Lake Trail". New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. Archived from the original on April 7, 2021. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- Mankiewicz & Mankiewicz 2002, p. 2.

- "Flushing Meadows Corona Park: Willow Lake Park – Invasive Phragmites". New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. Archived from the original on April 7, 2021. Retrieved April 27, 2017.

- Strategic Framework Plan, pp. 15, 18, 21.

- Sandomir, Richard (August 3, 2006). "ennis Center to Be Named for Billie Jean King". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 7, 2021. Retrieved April 27, 2017.

- Strategic Framework Plan, p. 15.

- Fetter, Henry D. (August 14, 2005). "The Queens Dodgers?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 7, 2021. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- Katz, Michael (September 15, 1974). "New York Grand Prix Project Considered Again — At Flushing Meadow Park But With a Lot of Ifs". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 7, 2021. Retrieved April 27, 2017.

- "New York May Get '83 Auto Grand Prix". The New York Times. October 28, 1982. Archived from the original on April 7, 2021. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

- "New York Grand Prix scheduled". Reading Eagle. UPI. October 28, 1982. pp. 41, 47. Archived from the original on May 21, 2020. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

- "No auto racing in New York". Boca Raton News. June 3, 1983. p. 2D. Archived from the original on May 21, 2020. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

- Purnick, Joyce (June 27, 1985). "AUTO RACE IN QUEENS CALLED OFF". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 7, 2021. Retrieved April 27, 2017.

- Harris, Mike (June 29, 1984). "U.S. Grand Prix success is vital to CART future". Daily News. Bowling Green, Kentucky. AP. p. 1–B. Archived from the original on May 21, 2020. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

- Willets Point DEIS 2013, p. 1⋅4.

- "Real estate developer Donald Trump has proposed building an ..." United Press International. New York. December 11, 1984. Archived from the original on April 7, 2021. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- Eskenazi, Gerald (February 7, 1986). "Jets Will Remain in New Jersey". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 7, 2021. Retrieved January 18, 2010.

- Meislin, Richard J. (April 11, 1987). "Plans for Domed Stadium in Queens in Doubt". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 7, 2021. Retrieved January 18, 2010.

- David Picker (December 5, 2012). "M.L.S. Promotes Stadium at a Town Hall Meeting". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 7, 2021. Retrieved January 22, 2013.

- Leight, Holly (May 13, 2013). "Be Our Guest: Major League Soccer Stadium Would Pollute Flushing Meadows-Corona Park". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on April 7, 2021. Retrieved June 3, 2014.

- Carlisle, Jeff (May 21, 2013). "Many Questions Surround Stadium Plans, NYC FC". ESPN. Archived from the original on December 31, 2013. Retrieved June 3, 2014.

- Bradley, Jeff (April 21, 2014). "NYCFC Announces Plans to Play at Yankee Stadium; No Timetable Given for Stay". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on April 24, 2014. Retrieved June 3, 2014.

- Rubinstein, Dana; Belson, Ken (November 15, 2022). "New York City Reaches Deal to Build Soccer Stadium in Queens". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 9, 2023. Retrieved March 29, 2023.

- "Nomads no more: NYCFC and NYC reach deal on soccer stadium in Queens". AM New York. November 15, 2022. Archived from the original on November 16, 2022. Retrieved November 15, 2022.

- "Boathouse to reopen soon at Meadow Lake". Queens Chronicle. Archived from the original on July 23, 2023. Retrieved January 15, 2020.

- "Strokes of Genius". United Federation of Teachers. Archived from the original on April 15, 2013. Retrieved October 3, 2012.

- "About TASCA". The American Small Craft Association. TASCA. Archived from the original on July 25, 2008. Retrieved April 7, 2008.

- "Mission". Archived from the original on August 28, 2008. Retrieved May 23, 2008. Flushing Meadows-Corona Park Conservancy: mission.

- "Flushing Meadows Corona Park Highlights - Willow Lake Trail : NYC Parks". New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. June 26, 1939. Archived from the original on April 7, 2021. Retrieved January 15, 2020.

- Colangelo, Lisa L. (May 1, 2013). "Nature lovers can now venture into Willow Lake Preserve in Flushing Meadows-Corona Park and explore it on their own". nydailynews.com. Archived from the original on April 7, 2021. Retrieved January 15, 2020.

- Kern-Jedrychowska, Ewa (June 3, 2013). "Reopened Trail Gives Forest Hills Residents Access to Willow Lake Preserve". DNAinfo New York. Archived from the original on January 15, 2020. Retrieved January 15, 2020.

- Velasquez, Aria (June 17, 2021). "NYC Park Lovers Say City Nature Trails Need More Green". THE CITY. Archived from the original on July 27, 2021. Retrieved July 27, 2021.

- Kilgannon, Corey (September 12, 2010). "CITY ROOM; Sweat; Wide World of Sports in a Queens Park". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 21, 2017. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- Staff, NYRR (August 23, 2023). "Corona Parksite=NYRR". Retrieved August 23, 2023.

- Schilling, John (June 23, 2023). "Thousands participate in annual NYRR Queens 10K at Flushing Meadows Corona Park". QNS.com. Retrieved August 23, 2023.

- "You Spin Me Right Round, Baby, Right Round Like a Carousel ..." WNET. March 7, 2012. Archived from the original on April 7, 2021. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- Walter Sullivan (September 22, 1966). "Hopeful Future Museum; But City's Hall of Science Still Retains Aura Reminiscent of the World's Fair". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 7, 2021. Retrieved April 6, 2008.

- NYC Parks Tomorrow's World 2015, p. 41.

- Rosenberg, Zoe (April 28, 2017). "New York State Pavilion preservation effort gets funding infusion". Curbed NY. Archived from the original on April 7, 2021. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

- Colangelo, Lisa L. (May 5, 2015). "Iconic New York State Pavilion in Flushing Meadows Corona Park getting $3 million facelift – FOR FREE". New York Daily News. NYDailyNews.com. Archived from the original on April 7, 2021. Retrieved July 27, 2015.

- Ruiz, Albor (July 21, 1997). "Swing Thru Latin America Via Fest". NY Daily News. Archived from the original on April 7, 2021. Retrieved April 5, 2017.

- "Flushing Meadows Corona Park Archived May 8, 2021, at the Wayback Machine" New York Magazine, December 11, 2015

- "Flushing Meadows Corona Park Highlights – Terrace on the Park". NYC Parks. Archived from the original on April 7, 2021. Retrieved April 5, 2017.

- Cotter, Holland (November 7, 2013). "A Local Place for a Global Neighborhood". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 30, 2023. Retrieved May 2, 2015.

- Cotter & Young 2014, pp. 55, 67; Historic Preservation Studio 2015, p. 18.

- "Playground for All Children". NYC Parks. Archived from the original on October 30, 2021. Retrieved June 20, 2015.

- Toomey, Paul. "Arthur Ashe Statue Unveiled By USTA At Flushing Meadows". Queens Chronicle. Archived from the original on July 23, 2023. Retrieved October 26, 2022.

- Berkow, Ira (September 7, 2000). "Sports of The Times; Bronze Guy Stands Tall Sans Towel". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 26, 2022. Retrieved October 26, 2022.

- "Soul in Flight: A Memorial to Arthur Ashe". Archived from the original on May 27, 2022. Retrieved October 26, 2022.

- Kaufman, Gil (January 7, 2022). "LL Cool J Statue in Queens Sustainably Rocks the Bells". Billboard. Retrieved October 26, 2022.

- Rahmanan, Anna (January 6, 2022). "You can actually charge your phone at this new tree-like sculpture in Queens". Time Out New York. Archived from the original on October 26, 2022. Retrieved October 26, 2022.

- Rahmanan, Anna. "A statue of rapper LL Cool J is now on display in Queens". Time Out New York. Archived from the original on October 26, 2022. Retrieved October 26, 2022.

- "MTA Neighborhood Maps: neighborhood". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. 2018. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- "MTA Neighborhood Maps: neighborhood". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. 2018. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- Strategic Framework Plan, p. 38.

- "Queens Bus Map" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. August 2022. Retrieved September 29, 2022.

- "Mayor: Valley of Ashes in 'Great Gatsby' Was Inspired by Willets Point". WNYC. June 14, 2012. Archived from the original on April 7, 2021. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- Hirshon, Nicholas (June 7, 2011). "'Men in Black III' crews turn the clock back to the 1960s in Queens". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on April 7, 2021. Retrieved April 18, 2017.

- "Men In Black 3 – Compositing Shea Stadium". YouTube. Sony Pictures Imageworks. February 26, 2015. Archived from the original on November 17, 2021. Retrieved April 18, 2017.

- "'The King of Queens' 2". Queens Chronicle. June 24, 2015. Archived from the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved June 23, 2021.

- Burrell, Jackie (September 29, 2014). "'Amazing Race' recap: Pearly whites, pen-swiping and pirates". The Mercury News. Archived from the original on April 7, 2021. Retrieved April 18, 2017.

- Pereira, Ivan (April 14, 2010). "Movie 'Iron Man 2' features expo in Flushing Meadows". QNS.com. Archived from the original on December 31, 2019. Retrieved March 9, 2019.

- Hirshon, Nicholas (May 7, 2010). "Relics from 1964 World's Fair in Flushing Meadows-Corona Park revived in 'Iron Man 2'". nydailynews.com. Archived from the original on December 31, 2019. Retrieved March 9, 2019.

- O'Sullivan, M. (2017). Marvel Cinematic Universe Guidebook: The Avengers Initiative. Marvel Entertainment. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-302-49692-0. Archived from the original on July 23, 2023. Retrieved March 9, 2019.

- Aswad, Jem (June 20, 2018). "Paul Simon to Stage 'Unique' Farewell Concert at Queens' Flushing Meadows Corona Park". Variety. Archived from the original on October 9, 2021. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

- Davenport, Emily (June 20, 2018). "Paul Simon to conclude his 'Farewell Tour' at Flushing Meadows Corona Park in September". QNS.com. Archived from the original on April 23, 2020. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

Sources

- 30 Years of Progress: 1934–1965 (PDF). New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. June 9, 1964. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- Caro, Robert (1974). The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York. New York: Knopf. ISBN 978-0-394-48076-3. OCLC 834874.

- Cotter, Bill; Young, Bill (January 20, 2014). The 1964–1965 New York World's Fair. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4396-4214-6. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- "Flushing Meadows-Corona Park: Historic Preservation Studio". Columbia Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation. May 3, 2015. Archived from the original on April 1, 2017. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- La Guardia International Airport and John F. Kennedy International Airport, Port Authority of New York and New Jersey Airport Access Program, Automated Guideway Transit System (NY, NJ): Environmental Impact Statement. Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, United States Department of Transportation, Federal Aviation Administration, New York State Department of Transportation. June 1994. Archived from the original on January 23, 2023. Retrieved March 28, 2017.