Fon people

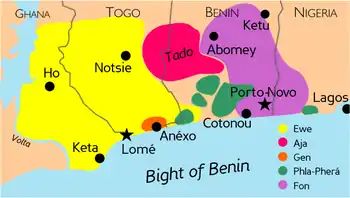

The Fon people, also called Fon nu, Agadja or Dahomey, are a Gbe ethnic group.[2][3] They are the largest ethnic group in Benin found particularly in its south region; they are also found in southwest Nigeria and Togo. Their total population is estimated to be about 3,500,000 people, and they speak the Fon language, a member of the Gbe languages.[2][4]

"Dahomey Amazon" by Élisée Reclus (1905) | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 5 million (including related groups like; Gun, Mahi, Ayizo, Weme) | |

| Languages | |

| Fon, French | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Gbe peoples |

| Person | Fon |

|---|---|

| People | Fon-nu |

| Language | fɔ̀ngbè |

| Country | Dahomey |

The history of the Fon people is linked to the Dahomey kingdom, a well-organized kingdom by the 17th century but one that shared more ancient roots with the Aja people.[3] The Fon people traditionally were a culture of an oral tradition and had a well-developed polytheistic religious system.[5] They were noted by early 19th-century European traders for their N'Nonmiton practice or Dahomey Amazons – which empowered their women to serve in the military, who decades later fought the French colonial forces in 1890.[6][7]

Most Fon today live in villages and small towns in mud houses with corrugated iron gable roofs. Cities built by the Fon include Abomey, the historical capital city of Dahomey on what was historically referred to by Europeans as the Slave Coast. These cities became major commercial centres for the slave trade. A significant portion of the sugar plantations in the French West Indies, particularly Haiti and Trinidad, were populated with slaves that came from the Slave Coast, through the lands of Ewe and Fon people.[8]

Origin

The Fon people, like other neighboring ethnic groups in West Africa, remained an oral tradition society through late medieval era, without ancient historical records. According to these oral histories and legends, the Fon people originated in present-day Tado, a small Aja town now situated near the Togo-Benin border. Their earliest rulers were originally a part of the ruling class in the Aja kingdom of Allada (also called Ardra kingdom).[3][8]

The Aja people had a major dispute, one group broke up and these people came to be the Fon people who migrated to Allada with king Agasu. The sons of king Agasu disputed who should succeed him after his death, and the group split again, this time the Fon people migrated with Agasu's son Dogbari northwards to Abomey where they founded the kingdom of Dahomey sometime about 1620 CE. The Fon people have been settled there since, while the kingdom of Dahomey expanded in southeast Benin by conquering neighboring kingdoms.[3]

The oral history of the Fon further attributes the origins of the Fon people to the intermarrying between this migrating Allada-nu Aja group from the south with the Oyo-nu inhabitants in the (Yoruba) Kingdoms of the plateau. These Yorubas were known as the Igede, which the Ajas called the Gedevi.[9][10] The fusion of the immigrant Aja conquerors and the original Indigenous Yorubas of the Abomey plateau thus created a new culture, that of the Fon.

Although these oral traditional origins have been passed down through the generations, they are not without controversy. The claim to an origin from within Allada is not recorded in contemporary sources before the late eighteenth century, and is likely a means of legitimating the claim and conquest of Allada by Dahomey in the 1720s.[11] These claims can also be interpreted as a metaphorical expressions of cultural and political influences between kingdoms rather than actual kinship.[12]

History

While references and documented history about the Fon people are scant before the 17th century, there are abundant documents on them from the 17th century, particularly written by European travelers and traders to West African coasts.[13] These memoirs mention such cities as Ouidah and Abomey. Among the most circulated texts are those of Archibald Dalzel, a slave trader who in 1793 wrote the legends, history and slave trading practices of the Fon people in a book titled the History of Dahomey.[14] Modern era scholars have questioned the objectivity and accuracy of Dalzel, and to what extent his pioneering book on Fon people was a polemic or dispassionate scholarship.[14]

In the 19th century and early 20th century, as the French presence increased and then the colonial period began in the Benin and nearby regions, more history and novels with references to the Fon people appeared, such as those by Édouard Foà,[15] N. Savariau,[16] Le Herisse and M.J. Herskovits' anthropological study on Fon people published in 1938.[13]

These histories suggest that Fon people's kingdom of Dahomey expanded in early 18th century, particularly during King Agaja's rule through the 1740s, reaching the Atlantic coast from their inland capital of Abomey.[3] During this period, 200 years after Portugal had already settled in the Kongo people lands on the Atlantic coast of Central Africa in the 16th century, there were numerous plantations in the Caribbean and Atlantic coastline of South America, which had already created a booming demand for slaves from the European traders. The expanded territory of the Dahomey kingdom was well positioned to supply this transatlantic trade and the 18th and 19th century history of the Fon people is generally presented within this context.[3][17][18]

Slavery, Bight of Benin

The Fon people did not invent slavery in Africa, nor did they have a monopoly on slavery nor exclusive slave trading activity. The institution of slavery long predates the origins of the Fon people in the Aja kingdom and the formation of the kingdom of Dahomey. The sub-Saharan and the Red Sea region, states Herbert Klein – a professor of history, was already trading between 5,000 and 10,000 African slaves per year between 800 and 1600 CE, with a majority of these slaves being women and children.[19] According to John Donnelly Fage – a professor of history specializing in Africa, a "slave economy was generally established in the Western and Central Sudan by about the fourteenth century at least, and had certainly spread to the coasts around the Senegal and in Lower Guinea by the fifteenth century".[20]

| Region | Total embarked | Total disembarked |

|---|---|---|

| West Central Africa | 5.69 million | |

| Bight of Benin | 2.00 million | |

| Bight of Biafra | 1.6 million | |

| Gold Coast | 1.21 million | |

| Windward Coast | 0.34 million | |

| Sierra Leone | 0.39 million | |

| Senegambia | 0.76 million | |

| Mozambique | 0.54 million | |

| Brazil (South America) | 4.7 million | |

| Rest of South America | 0.9 million | |

| Caribbean | 4.1 million | |

| North America | 0.4 million | |

| Europe | 0.01 million |

By the 15th century, Songhay Empire rulers to the immediate north of the Fon people, in the Niger River valley, were already using thousands of captured slaves for agriculture.[19] The demand for slave labor to produce sugarcane, cotton, palm oil, tobacco and other goods in the plantations of European colonies around the globe had sharply grown between 1650 and 1850. The Bight of Benin was already shipping slaves in the late 17th century, before the Fon people expanded their kingdom to gain control of the coast line.[22] The Fon rulers and merchants, whose powers were established on the Atlantic coast between 1700 and 1740, entered this market.[20] The Fon people were divided on how to respond to the slave demand. Some scholars suggest that Fon people and Dahomey rulers expressed intentions to curtail or end slave trading, states Elizabeth Heath, but historical evidence affirms that the Benin coastline including the ports of the Dahomey rulers and the Fon people became one of the largest exporter of slaves.[3]

The kingdom of Dahomey, along with its neighbors' kingdoms of Benin and Oyo Empire, raided for slaves and sold their captives into transatlantic slavery. The competition for captives, slaves and government revenues, amongst the African kingdoms, escalated the mutual justification and pressure. The captives were sold as slaves to the Europeans from the Bight of Benin (also called the Slave Coast), from the eighteenth to the nineteenth century.[23] The Fon people were both victims and also victimized other ethnic groups. Some captives came from wars, but others came from systematic kidnapping within the kingdom or at the frontiers, as well as the caravans of slaves brought in by merchants from the West African interior. The kingdom of Dahomey of Fon people controlled the port Ouidah, from where numerous European slave ships disembarked. However, this was not the only port of the region and it competed with the ports controlled by other nearby kingdoms on the Bight of Benin and the Bight of Biafra.[23]

The Fon people, along with the neighboring ethnic groups such as the Ewe people, disembarked in French colonies to work as slaves in the plantations of the Caribbean and coasts of South America. They were initially called Whydah, which probably meant "people sold by Alladah". The word Whydah phonetically evolved into Rada, the name of the West African community that embarked in slave ships from the Bight of Benin, and is now found in Haiti, Saint Lucia, Trinidad, French Antilles and other nearby islands with French influence.[8] In some Caribbean colonial documents, alternate spellings such as Rara are also found.[24]

The slave traders and ship owners of European colonial system encouraged competition, equipped the various kingdoms with weapons, which they paid for with slaves, as well as built infrastructure such as ports and forts to strengthen the small kingdoms.[25] However, slave trading in the Bight of Benin soon came to an end as European and American nations passed legislation which outlawed their involvement in the slave trade. The last nation in the Americas to officially outlaw the slave trade was Imperial Brazil, in 1851.[3][26] When slave exports ceased, the king of the Fon people shifted to agricultural exports to France, particularly palm oil, but used slaves to operate the plantations. The agricultural exports were not as lucrative as slave exports had been in past. To recover state revenues he leased the ports in his kingdom to the French through a signed agreement in late 19th century. The French interpreted the agreement as ceding the land and ports, while the Dahomey kingdom disagreed.[3] The dispute led to a French attack in 1890, and annexation of the kingdom as a French colony in 1892.[27] This started the colonial rule for the Fon people.[3]

French colonial era

The period of French colonial empire marked the end of the Fon royalty, though France kept the system of plantations, which they had inherited from the royalty.[27] The only difference, so states Patrick Manning – a professor of World History specializing on Africa, for the next seventy years was that the French colonial state, instead of the former king of Fon people, now decided how the surplus (profits) from these plantations were to be spent.[27] The French colonial administrators made some infrastructure improvements to improve the plantation profitability and logistics to serve French colonial interests.[28]

The French colonial administration targeted slavery in Benin, they outlawed capture of slaves, legally freed numerous slaves, but faced resistance and factional struggles from previous local slave owners running their farms. The slavery that continued included those that was lineage-related, who cohabited within families in the region. The Fon aristocracy adapted to the new conditions, by joining the ranks of administrators in the French rule.[27]

Taxes new to the Dahomey colony's people, which the French called impôt, similar to those already practiced in France, were introduced on all ethnic groups, including the Fon people, by the colonial administrators. Payment of these were regularly resisted or just refused, leading to confrontations, revolts, arrests, prison terms and forced labor.[29] These complaints gelled into an anti-colonial nationalism movement in which the Fon people participated.[29] France agreed to autonomy to Dahomey in 1958, and full independence in 1960.[30]

Religion

Some Fon people converted to Christianity or Islam under the influence of missionaries during the colonial era, in Benin and in French West Indies colonies, but many continued their traditional religious practices.[31] While Islam arrived in the Benin area between 11th and 13th centuries, Christianity was adopted by Dahomey ruler Agonglo who came to power in 1789, and his Fon royalty supporters, with missionaries welcomed.[32] According to Steven Mailloux, the missionaries attempted to integrate the old concepts of Fon people on cosmogenesis to be same as Adam-Eve, and their Legba to be Christian Satan, teachings that led to syncretism rather than abandonment.[33]

The Fon people, states Mary Turner, have generally proven to be highly resistant to Christianity and Islam, even when brought over as slaves in a new environment as evident in Afro-Jamaican[34] and other African influenced cultures with ties to the Slave Coast.[35] They have generally refused to accept innovative re-interpretation of Fon mythologies within the Abrahamic mythical framework.[36] The priests of the Fon people, contrary to the expectations of the missionaries, adopted and re-interpreted Abrahamic myths into their own frameworks.[37]

Traditional beliefs

The traditional Fon religion is regionally called Vodoun, Vodzu or Vodu, which is etymologically linked to Vodun – a term that refers to their theological concept of "numerous immortal spirits and deities".[8][38]

The religious practice of the Fon people have four overlapping elements: public gods, personal or private gods, ancestral spirits, and magic or charms.[5] Thus, the Vodoun religion is polytheistic. The Fon people have a concept of a female Supreme Being called Nana Buluku, who gave birth to the Mawu-Lisa and created the universe.[5] After giving birth, the mother Supreme retired, and left everything to Mawu-Lisa (Moon-Sun, female-male) deities, spirits and inert universe. Mawu-Lisa created numerous minor imperfect deities. In Fon belief, the feminine deity Mawu had to work with trickster Legba and the cosmic serpent Aido Hwedo to create living beings, a method of creation that imbued the good, the bad and a destiny for every creature including human beings. Only by appeasing lesser deities and Legba, in Fon theology, can one change that destiny. This appeasing requires rituals and offerings to the lesser gods and ancestral spirits, who are believed to have ability to do favors to human beings.[5][39][40] A typical traditional home compound of the Fon people has a Dexoxos, or ancestral shrine.[5] The charms are locally called gbo, gris gris, ju ju, or obeah, involve leaves, herbs, smoke and these are offerings to public or personal gods of each family.[5]

While many Fon identify as Christian, the majority continue to practice Benin's traditional religion Vodun. The Fon have priests and mediums who receive the spirits on the occasion of the great festivals. The cult of the sacred serpents in the temple of Whydah had some importance, but eventually fell into disuse.[43] Practice can involve drumming to induce possession by one of these gods or spirits. Together with other cultural groups from the Fon homeland region such as the Yoruba and Bantu, Fon culture merged with French, Portuguese or Spanish to produce distinct religions (Voodoo, Obeah, Candomblé and Santería), dance and musical styles (Arará, Yan Valu).

In the French colonies, such as Saint-Domingue (now Haiti), the Christian missionaries confiscated and burnt the statues and religious objects of the Fon people, but this did not end their practices. They rebuilt their icons again.[44] The Fon people and their government have reversed the colonial attempts to culturally change them. After the end of the colonial era, January 10 has been declared an official annual holiday in Benin dedicated to Vodun gods.[45]

Society and culture

The Fon people are traditionally settled farmers, growing cassava, corn and yams as staples.[2] The men prepare the fields, women tend and harvest the crop. Hunting and fishing are other sources of food, while some members of the Fon society make pottery, weave clothes and produce metal utensils. Among the cash crops, palm oil plantations are common in Fon people's region. The Fon culture is patrilineal and allows polygyny and divorce. A man with multiple wives usually lived in a compound with each wife and her children occupying a separate hut. A collection of compounds formed a village, usually headed by a hereditary chief. In contemporary times, traditional patrilineal clan-based living and associated practices are uncommon.[2]

Funerals and death anniversaries to remember their loved ones are important events, including drumming and dancing as a form of mourning and celebrating their start of life as a spirit by the one who died, can last for days.[47][48]

The Fon culture incorporated culture and shared ideas with ethnic groups that have been their historical neighbors. Many of their practices are found among Yoruba people, Akan people, Ewe people and others.[49]

Dahomey Amazons

A notable part of the Fon people's society was their use of female soldiers in combat roles over some two centuries. Over 3,000 women trained and served as regular warriors to protect the Fon and to expand its reach. The women warrior's brigade was led by a woman.[50][51]

Given the oral tradition of Fon people, when women joined as warriors in Fon society is unclear. The earliest European records, such as those of Jean-Pierre Thibault, suggest that the tradition dates back to the early 18th century or even earlier.[50] These gender roles were foreign to the European travelers, and early fictional stories in European media are considered unreliable by many scholars.[6]

See also

Notes

- This slave trade volume excludes the slave trade by Swahili-Arabs in East Africa and North African ethnic groups to the Middle East and elsewhere. The exports and imports do not match, because of the large number of deaths and violent retaliation by captured people on the ships involved in the slave trade.[21]

References

- Fon people, Encyclopædia Britannica, undated, 1.7 million population, Retrieved June 29, 2019

- Elizabeth Heath (2010). Anthony Appiah; Henry Louis Gates (eds.). Encyclopedia of Africa. Oxford University Press. pp. 482–483. ISBN 978-0-19-533770-9.

- III, John A. Shoup (2011). Ethnic Groups of Africa and the Middle East: An Encyclopedia: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-363-7.

- Molefi Kete Asante; Ama Mazama (2009). Encyclopedia of African Religion. Sage Publications. pp. 270–273, 257, 412. ISBN 978-1-4129-3636-1.

- Robin Law (1993), The 'Amazons' of Dahomey, Paideuma: Mitteilungen zur Kulturkunde, Bd. 39 (1993), pp. 245–260

- Alpern, Stanley B. (1998). "On the Origins of the Amazons of Dahomey". History in Africa. Cambridge University Press. 25: 9–25. doi:10.2307/3172178. JSTOR 3172178. S2CID 162412301.

- Patrick Taylor; Frederick I. Case (2013). The Encyclopedia of Caribbean Religions. University of Illinois Press. pp. 742–746, 1134–1139. ISBN 978-0-252-09433-0.

- "The Kingdom of Abomey, the Royal Palaces of Abomey - Evenemenciel". Archived from the original on 2017-09-02. Retrieved 2017-09-02.

- Sandra T. Barnes (1997). Africa's Ogun, Second, Expanded Edition: Old World and New. Indiana University Press. p. 49. ISBN 0-253-11381-4.

- Law, Robin (1991). The Slave Coast of West-Africa 1550-1750. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 27. ISBN 0-19-820228-8.

- Miller, Joseph C. (1980). The African Past Speaks: Essays on Oral Tradition and History. Folkestone: Archon Books. p. 31-4. ISBN 0208017844.

- Patrick Manning (2004). Slavery, Colonialism and Economic Growth in Dahomey, 1640-1960. Cambridge University Press. pp. xv–xvi. ISBN 978-0-521-52307-3.

- I. A. Akinjogbin (1966), Archibald Dalzel: Slave Trader and Historian of Dahomey, The Journal of African History, Cambridge University Press, Vol. 7, No. 1 (1966), pages 67-78

- Le Dahomey, Édouard Foà (1895), BnF: National Library of France (in French)

- L'agriculture au Dahomey N. Savariau (1906), A. Challamel, Marseille, France, Exposition nationale (in French)

- Law, Robin; Mann, Kristin (1999). "West Africa in the Atlantic Community: The Case of the Slave Coast". The William and Mary Quarterly. 56 (2): 307. doi:10.2307/2674121. JSTOR 2674121.

- Herbert S. Klein (26 April 2010). The Atlantic Slave Trade. Cambridge University Press. pp. 53, 64–65, 53–68. ISBN 978-1-139-48911-9.

- Herbert S. Klein (2010). The Atlantic Slave Trade. Cambridge University Press. pp. 7–9. ISBN 978-1-139-48911-9.

- Fage, J. D. (1969). "Slavery and the Slave Trade in the Context of West African History". The Journal of African History. Cambridge University Press. 10 (3): 393–404. doi:10.1017/s0021853700036343. S2CID 162902339.

- David Eltis and David Richardson (2015), Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, 2nd Edition, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0300212549; Archive: Slave Route Maps, see Map 9; The transatlantic slave trade volume over the 350+ years involved an estimated 12.5 million Africans, almost every country that bordered the Atlantic Ocean, as well as Mozambique and the Swahili coast.

- Patrick Manning (2004). Slavery, Colonialism and Economic Growth in Dahomey, 1640-1960. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–3, 12–15. ISBN 978-0-521-52307-3.

- Herbert S. Klein (26 April 2010). The Atlantic Slave Trade. Cambridge University Press. pp. 64–65, 53–68. ISBN 978-1-139-48911-9.

- Rosanne Marion Adderley (2006). "New Negroes from Africa": Slave Trade Abolition and Free African Settlement in the Nineteenth-century Caribbean. Indiana University Press. p. 99. ISBN 0-253-34703-3.

- Anne Caroline Bailey (2005). African Voices of the Atlantic Slave Trade: Beyond the Silence and the Shame. Beacon Press. pp. 69–75, 175. ISBN 978-0-8070-5512-0.

- CHRONOLOGY - Who banned slavery when? Reuters

- Patrick Manning (2004). Slavery, Colonialism and Economic Growth in Dahomey, 1640-1960. Cambridge University Press. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-0-521-52307-3.

- Patrick Manning (2004). Slavery, Colonialism and Economic Growth in Dahomey, 1640-1960. Cambridge University Press. pp. 15–18. ISBN 978-0-521-52307-3.

- Patrick Manning (2004). Slavery, Colonialism and Economic Growth in Dahomey, 1640-1960. Cambridge University Press. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-0-521-52307-3.

- Jamie Stokes (2009). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East. Infobase. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-4381-2676-0.

- E.A. Ayandele (2013). 'Holy' Johnson, Pioneer of African Nationalism, 1836-1917. Routledge. pp. 197–198. ISBN 978-1-136-25196-2.

- Toyin Falola; Daniel Jean-Jacques (2015). Africa: An Encyclopedia of Culture and Society. ABC-CLIO. pp. 54–56. ISBN 978-1-59884-666-9.

- Steven Mailloux (1998). Reception Histories: Rhetoric, Pragmatism, and American Cultural Politics. Cornell University Press. pp. 15–16. ISBN 0-8014-8506-1.

- Davis, Nick (13 August 2013). "Obeah: Resurgence of Jamaican 'Voodoo'". BBC News.

- Mary Turner (1982). Slaves and Missionaries: The Disintegration of Jamaican Slave Society, 1787-1834. Press University of the West Indies. pp. 55–56. ISBN 978-976-640-045-3.

- Walter Jost; Michael J. Hyde (1997). Rhetoric and Hermeneutics in Our Time: A Reader. Yale University Press. p. 389. ISBN 978-0-300-06836-8., Quote: "They [Christian missionaries visiting Fon in Dahomey] cited one of the Fon creation myths (...) as a corrupted version of the Adam and Eve story. But the Fon were not persuaded by this interpretation. (..., the Fon people said:) 'But the missionaries, when they heard our [deities] name of Adanhu and Yewa, said our gods and theirs were all the same. They tried to teach us the rest about the beginning of man and woman, but the Dahomeans, the Fon, do not agree'. They say this is not their story. They know nothing about Legda trying to give fruit."

- Desmangles, Leslie Gerald (1977). "African Interpretations of the Christian Cross in Vodun". Sociological Analysis. Oxford University Press. 38 (1): 13–15. doi:10.2307/3709833. JSTOR 3709833.

- Molefi Kete Asante; Ama Mazama (2009). Encyclopedia of African Religion. SAGE Publications. p. 283. ISBN 978-1-4129-3636-1.

- Sara A. Rich (2009), The Face of "Lafwa": Vodou & Ancient Figurines Defy Human Destiny, Journal of Haitian Studies, Vol. 15, No. 1/2, Haitian Studies Association 20thAnniversary Issue (Spring/Fall 2009), pages 262-278

- Cosentino, Donald (1987). "Who Is That Fellow in the Many-Colored Cap? Transformations of Eshu in Old and New World Mythologies". The Journal of American Folklore. 100 (397): 261–275. doi:10.2307/540323. JSTOR 540323.

- Mike Dash (May 2013), The Trial That Gave Vodou A Bad Name, Smithsonian Magazine

- Kate Ramsey (2011). The Spirits and the Law: Vodou and Power in Haiti. University of Chicago Press. pp. 83–87. ISBN 978-0-226-70380-0."Quote: "The prisoners were bullied, cajoled... (...) I can never forget the manner in which the youngest female prisoner, Roseide Sumera turned to the public prosecutor and said, 'Yes, I did confess what you assert, but remember how cruelly I was beaten before I said a word' – Spenser St John, British minister to Haiti who witnessed the trial."

- Archived 2012-02-03 at the Wayback Machine EL ELEMENTO SUBSAHÁRICO EN EL LÉXICO venezolano (in Spanish: The Sub-Saharan element in the Venezuelan lexicon)

- Michael Laguerre (1973), The place of Voodoo in the Social Structure of Haiti, Caribbean Quarterly, Vol. 19, No. 3 (Sept 1973), pages 36-50

- J. Lorand Matory (2010). Anthony Appiah; Henry Louis Gates (eds.). Encyclopedia of Africa. Oxford University Press. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-19-533770-9.

- Curator's Choice: Islam in Africa, Fon Brooklyn Museum

- Toyin Falola; Daniel Jean-Jacques (2015). Africa: An Encyclopedia of Culture and Society. ABC-CLIO. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-59884-666-9.

- Renée Larrier; Ousseina Alidou (2015). Writing through the Visual and Virtual: Inscribing Language, Literature, and Culture in Francophone Africa and the Caribbean. pp. 163–164. ISBN 978-1-4985-0164-4.

- Mary Ann Clark (2012). Then We'll Sing a New Song: African Influences on America's Religious Landscape. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 135–136. ISBN 978-1-4422-0881-0.

- Dahomey’s Women Warriors, Smithsonian Magazine

- Stanley B. Alpern (11 April 2011). Amazons of Black Sparta: The Women Warriors of Dahomey. NYU Press. pp. ix–x, 16–22. ISBN 978-0-8147-0772-2.

External links

Media related to Fon people at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Fon people at Wikimedia Commons