Force concentration

Force concentration is the practice of concentrating a military force so as to bring to bear such overwhelming force against a portion of an enemy force that the disparity between the two forces alone acts as a force multiplier in favour of the concentrated forces.

| Part of a series on |

| War |

|---|

Mass of decision

Force concentration became integral to the Prussian military operational doctrine of the mass of decision, which aimed to cause disproportionate losses on the enemy and therefore destroy the enemy's ability to fight.

From an empirical examination of past battles, the Prussian military theorist Carl von Clausewitz (1780–1831) concluded:

[...] we may infer, that it is very difficult in the present state of Europe, for the most talented General to gain a victory over an enemy double his strength. Now if we see double numbers prove such a weight in the scale against the greatest Generals, we may be sure, that in ordinary cases, in small as well as great combats, an important superiority of numbers, but which need not be over two to one, will be sufficient to ensure the victory, however disadvantageous other circumstances may be.[1]

Lanchester's laws

During the First World War Frederick W. Lanchester formulated Lanchester's laws that calculated that the combat power of a military force is the square of the number of members of that unit so that the advantage a larger force has is the difference of the squares of the two forces,[2][3] i.e.

- If force A has say 2 units and force B has 3 units, then the advantage force B has is 3²−2² or 5.

- If force A still has 2 units and force B has 4 units then the advantage force B has is 4²−2² or 12.

- If force A still has 2 units and force B has 5 units then the advantage force B has is 5²−2² or 21.

So a two to one advantage in units will quadruple the firepower and inflict four times the punishment, three times as many units will have nine times the combat ability and so on. Basically the greater the numerical superiority that one side has, the greater the damage he can inflict on the other side and the smaller the cost to himself.

Mathematical model

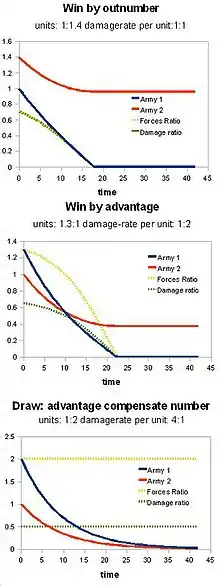

There is no battlefield where battle tactics can be reduced to a pure race of delivering damage while ignoring all other circumstances. However, in some types of warfare, such as a battle for air superiority, confrontation of armoured forces in World War II or battleship-based naval battles, the ratio of armed forces could become the dominant factor. In that case, equations stated in Lanchester's laws model the potential outcome of the conflict fairly well. Balance between the two opponent forces incline to the side of superior force by the factor of . For example, two tanks against one tank are superior by a factor of four.

This result could be understood if the rate of damage (considered as the only relevant factor in the model) is solved as a system of differential equations. The rate in which each army delivers damage to the opponent is proportional to the number of units – in the model each unit shoots at a given rate – and to the ability or effectiveness of each surviving unit to kill the enemy. The sizes of both armies decrease at different rates depending on the size of the other, and casualties of the superior army approach zero as the size of the inferior army approaches zero. This can be written in equations:

- is the number of units in the first army

- is the rate in which army 1 damages army 2 (affected by unit quality or other advantage)

- is a coefficient which describes army 1's ability to inflict damage per unit per time.

The above equations result in the following homogeneous second-order linear ordinary differential equations:

To determine the time evolution of and , these equations need to be solved using the known initial conditions (the initial size of the two armies prior to combat).

This model clearly demonstrates (see picture) that an inferior force can suffer devastating losses even when the superior force is only slightly larger, in case of equal per-unit qualitative capabilities: in the first example (see picture, top plot) the superior force starts only 40% larger, yet it brings about the total annihilation of the inferior force while suffering only 40% losses. Quality of the force may outweigh the quantitative inferiority of the force (middle plot) when it comes to battle outcomes.

Business strategy

In the 1960s, Lanchester's laws were popularised by the business consultant Nobuo Taoka and found favour with a segment of the Japanese business community.[4] The laws were used to formulate plans and strategies to attack market share. The "Canon–Xerox copier battle" in the UK, for example, reads like a classic people's war campaign. In this case, the laws supported Canon's establishment of a "revolutionary base area" by concentrating resources on a single geographical area until dominance could be achieved, in this case in Scotland. After this, they carefully defined regions to be individually attacked again with a more focused allocation of resources. The sales and distribution forces built up to support these regions in turn were used in the final "determined push in London with a numerically larger salesforce".

Hypothetical example

Imagine two equally matched sides each with two infantry and two armoured divisions. Now visualize a straight defensive line with the two infantry and two armoured divisions, deployed equally along the length of the line. Hypothetically the attacker can win by concentrating his armour at one point (with his infantry holding the rest of the line).

Traditionally it is accepted that a defending force has a 3:1 advantage over an attacker. In other words, a defending force can hold off three times its own number of attackers.[5][6][7] Imagine, then, that the defensive line is four units in length, so that each portion of the line can be held by a single defending division. Assume that they can take on the oncoming armour on equal terms (with ATGWs, pre-prepared artillery fireplans etc.) and that they have had time to dig in. This single unit should be able to hold off 3 times its own number. With the attacking force having only two armoured units, the defenders should have the advantage.

However, as the defensive line increases from the imaginary four units in length, the advantage slips from the defender to the attacker. The longer the line to be held, the thinner the defenders will be spread. With the defender having sacrificed his mobility to dig in, the attacker can choose where and when to attack. Either penetrating the line or turning a flank and thus being able to destroy the enemy in detail. Thus, concentrating two divisions and attacking at a single point generates a far greater force than is achieved by spreading two divisions into a line and pushing forward on a broad front.

Concentration of force in this scenario requires mobility (to permit rapid concentration) and power (to be effective in combat once concentrated). The tank embodies these two properties and for the past seventy years has been seen as the primary weapon of conventional warfare.

No one side has a monopoly on military art, and what is obvious to one side is obvious to the other. A far more likely scenario is that both forces will choose to use their infantry to hold a line and to concentrate their armour, and rather than a line in the sand, the infantry line would be more of a trip wire, to warn of where the enemy has chosen to launch his attack, with the armoured forces jostling to find the right place to attack or counterattack. Other considerations, then, must come into play for a decisive blow to be achieved.

Such considerations may be economic or political in nature, e.g. one side is unable or unwilling to allow the sanctity of its soil to be violated, and thus insists on defending a line on a map.

History

Force concentration has been a part of the military commander's repertoire since the dawn of warfare, though maybe not by that name. Commanders have always tried to have the advantage of numbers. The declined flank for example, was one way of achieving a force concentration during a battle.

Disposition of Roman Legions

At the beginning of the Roman Empire, in the first years of the first millennium, Rome's Legions were grouped into battle groups of three or four Legions, on the Rhine, on the Danube and in the Levant. By the third century A.D. these Legions had been dispersed along the frontiers in frontier fortifications, and within the Empire as internal security troops. In the first case Rome's military might was disposed in a manner in which it had a concentration of force capable of offensive action; in the second case it could defend effectively but could only attack and counterattack with difficulty.

Guerrilla warfare

As they are usually the smaller in number an appreciation of force concentration is especially important to guerrilla forces, who find it prudent initially to avoid confrontations with any large concentrations of government/occupying forces. However, through the use of small attacks, shows of strength, atrocities etc. in out of the way areas, they may be able to lure their opponents into spreading themselves out into isolated outposts, linked by convoys and patrols, in order to control territory. The guerrilla forces may then attempt to use force concentrations of their own; using unpredictable and unexpected concentrations of their forces, to destroy individual patrols, convoys and outposts. In this way they can hope to defeat their enemy in detail.

Regular forces, in turn, may act in order to invite such attacks by concentrations of enemy guerrillas, in order to bring an otherwise elusive enemy to battle, relying on its own superior training and firepower to win such battles. This was successfully practiced by the French during the First Indochina War at the Battle of Nà Sản, but a subsequent attempt to replicate this at Dien Bien Phu led to decisive defeat.

Aerial warfare

During World War I the Central Powers became increasingly unable to meet the Allied Powers in terms of outright number of fighter aircraft. To overcome this shortcoming rather than deploying their fighters uniformly along the fronts, the Germans concentrated their fighters into large mobile Jagdgeschwader formations, the most famous of which was Manfred von Richthofen's Flying Circus, that could be moved rapidly and unexpectedly to different points along the front. This allowed them to create a local superiority in numbers, that could achieve air supremacy in a local area in support of ground operations or just to destroy Allied fighters in the overall strategy of attrition.

Similarly the Second World War Big Wing was one tactic that was evolved to cause maximum damage to the enemy with the minimum of casualties.

Blitzkrieg

Modern armour warfare doctrine was developed and established during the run up to World War II. A fundamental key to conventional Warfare is the concentration of force at a particular point (the [der] Schwerpunkt). Concentration of force increases the chance of victory in a particular engagement. Correctly chosen and exploited, victory in a given engagement or a chain of small engagements is often sufficient to win the battle.

Defence of France 1944

The Nazi defence of France in 1944 could have followed one of the two models offered in the hypothetical example. The first was to distribute the available forces along the Atlantic Wall and throw the invading Allies back into the sea where and when they landed. The second was to keep the German Panzers concentrated and well away from the beaches. Territory could then be conceded to draw the invasion force away from their lodgement areas from which it would be nipped off by the cutting of their supply lines and then defeated in detail. The superiority of concentrated forces using maneuver warfare in the hypothetical example carried the proviso of "all other things being equal"; by 1944 things were far from being equal.

With Allied air superiority not only were major force concentrations vulnerable to tactical and heavy bombers themselves, but so were the vital assets—bridges, marshalling yards, fuel depots, etc.—needed to give them mobility. As it was in this case, the blitzkrieg solution was the worst of both worlds, neither being far enough forward to maximise the use of their defensive fortifications, nor far enough away and concentrated to give it room to manoeuvre.

Similarly, for the Japanese in the final stages of the Island hopping campaign of the Pacific War, with Allied naval and air superiority and non-existent room to manoeuvre, neither a water's edge defensive strategy nor a holding back and counterattacking strategy could succeed.

Cold War and beyond

For much of the Cold War, to combat the overwhelming Soviet supremacy in armour and men, NATO planned to use much of West German territory as a flood plain in a defence in depth to absorb and disperse the momentum of a massed Soviet attack. Mobile anti-tank teams and counterattacking NATO armies would seek to cut off the leading Soviet echelons from their supporting echelons and then reduce the isolated elements with superior air power and conventional munitions, and if this failed, with nuclear munitions.

In an effort to avoid the use of nuclear munitions in an otherwise conventional war, the US invested heavily in a family of technologies it called "Assault Breaker", the two parts of these programmes were an enhanced realtime intelligence, surveillance, target acquisition, and reconnaissance capability, and the second part a series of stand off precision guided air-launched and artillery weapon systems, such as the MLRS, ICMs, M712 Copperhead, and the BLU-108 submunition. Against such weapons massed concentrations of armour and troops would no longer be a virtue but a liability. From the mid eighties and onward a much greater level of force dispersal became desirable rather than concentration.

See also

References

-

von Clausewitz, Karl (1909). "Book 3 (Of strategy in general): Superiority_of_numbers". Vom Kriege [On War]. London. Retrieved 2016-04-27.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "Article at Lanchester Press". Archived from the original on 2007-06-29. Retrieved 2007-05-06.

- Lanchester, F.W., "Mathematics in Warfare" in The World of Mathematics, Vol. 4 (1956) Ed. Newman, J.R., Simon and Schuster, 2138–2157

- "A British Military Theory Finds Favour Among Japan's Businesses". Archived from the original on 2007-04-18. Retrieved 2007-05-11.

- Mearsheimer, John J. (1989). "Assessing the Conventional Balance: The 3:1 Rule and Its Critics". International Security. 13 (4): 54–89. doi:10.2307/2538780. ISSN 0162-2889. JSTOR 2538780. S2CID 154036000.

- Epstein, Joshua M. (1988). "Dynamic Analysis and the Conventional Balance in Europe". International Security. 12 (4): 154–165. doi:10.2307/2538999. ISSN 0162-2889. JSTOR 2538999. S2CID 153344264.

- Mearsheimer, John J. (1982). "Why the Soviets Can't Win Quickly in Central Europe". International Security. 7 (1): 3–39. doi:10.2307/2538686. ISSN 0162-2889. JSTOR 2538686. S2CID 154732192.

Sources

- Carl von Clausewitz, On War, online version available, especially Book 3, Chapter VIII ("Superiority of Numbers"), and Chapter XI ("Assembly of Forces in Space").

- Dunnigan, James F. How To Make War, 2003, HarperCollins Publishers, New York.