Fort Glass

Fort Glass was a stockade fort built in July 1813 in present-day Clarke County, Alabama during the Creek War (part of the larger War of 1812).[2]

| Fort Glass | |

|---|---|

| Suggsville, Alabama in United States | |

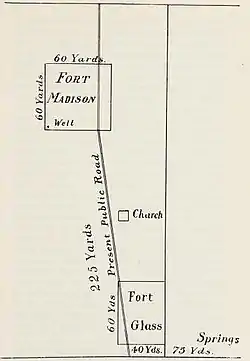

Sketch of Fort Glass and Fort Madison | |

Fort Glass  Fort Glass | |

| Coordinates | 31°31′19″N 87°43′08″W[1] |

| Type | Stockade fort |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Private |

| Controlled by | Private |

| Open to the public | No |

| Site history | |

| Built | July 1813 |

| Built by | Mississippi Territory settlers |

| In use | 1813 |

| Battles/wars | Creek War |

History

Background

The Creek War of 1813 began as a civil war between supporters of the Creek national government and a rebel faction called Red Sticks. Americans, who were already engaged in the War of 1812 against Britain, joined the Creek war in the hope of breaking Creek power and depriving the British of a potential ally.[3]

The American settlers became fearful after these Creek attacks and were unsure if the United States would protect them due to fact they were squatters on public lands. To protect themselves the settlers built temporary stockades, and most were named for the person who owned the land the stockade was built on. After the Creek War, most of these forts were dismantled.[2]

Creek War

Fort Glass was built in 1813 by and named for Zachariah Glass.[4] The fort was rectangular in shape, sixty yards by forty yards, and constructed of hewn pine logs.[5]

After completion, Samuel Dale stopped at Fort Glass on his way to Georgia. The occupants asked him to stay and he was given command of Fort Glass for a brief time.[6]

En route from Fort St. Stephens to intercept Peter McQueen's party of Red Sticks who were returning from Pensacola with supplies, Colonel James Caller stopped at Fort Glass after passing through Jackson.[7] Upon leaving Fort Glass, additional reinforcements joined Caller including a party of volunteers from Fort Glass led by Dale. These volunteers participated in the Battle of Burnt Corn on July 27, 1813.[8]

After the Battle of Burnt Corn, General Ferdinand Claiborne feared swift revenge on part of the Red Sticks. Claiborne sent Colonel Joseph Carson with two hundred mounted soldiers to Fort Glass as reinforcements to protect the settlers in the surrounding area. These soldiers arrived at Fort Glass on August 10, 1813.[9] Soon after their arrival, the soldiers began construction of a new fort located two hundred and twenty-five yards northwest of Fort Glass. This new fort was named Fort Madison in honor of then-President James Madison.[10] Soldiers remained in Fort Glass and Fort Madison, but Fort Madison was made the headquarters for the surrounding military district after it was constructed.[11] This district included the territory between the Alabama and Tombigbee Rivers.[12]

After the Red Stick attack on Fort Sinquefield, the settlers who occupied Fort Sinquefield fled to Fort Glass and Fort Madison for protection. Ten men from Fort Glass went to Fort Sinquefield to recover bodies of the slain and to assist with burials.[13] After news of the Fort Sinquefield attack reached Fort Glass, Jeremiah Austill traveled by horseback to inform General Claiborne at Mount Vernon, stopping overnight at Fort Carney.[14]

References

- "GNIS Detail - Fort Glass". U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 27 April 2021.

- "National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form". Department of the Interior. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- Braund, Kathryn. "Creek War of 1813-1814". Alabama Humanities Alliance. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

- Harris 1977, pp. 109.

- Halbert & Ball 1895, pp. 109.

- Owen 1898, pp. 96.

- "Forts and Battle Sites Alabama". Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- Rowland 1921, pp. 35.

- Pickett 1878, pp. 526.

- Ball 1994, pp. 318.

- Eggleston 1878, pp. 121.

- Rowland 1921, pp. 61.

- Eggleston 1875, pp. 17.

- Halbert & Ball 1895, pp. 200.

- Ball 1994, pp. 571.

- Braund 2012, pp. 250.

Sources

- Ball, Timothy Horton (1994) [1882]. A Glance into the Great South-East, or Clarke County, Alabama, and its surroundings, from 1540 to 1877. Grove Hill, Alabama: Clarke County Historical Society. OCLC 1009338180.

- Braund, Kathryn E. Holland (2012). Tohopeka: Rethinking the Creek War & the War of 1812. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-5711-5.

- Eggleston, George Cary (1878). Red Eagle and the Wars with the Creek Indians of Alabama. New York, New York: Dodd, Mead & Company. ISBN 9780548127322.

- Eggleston, George Cary (1875). The Big Brother: A Story of Indian War. New York, New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. ISBN 9798740712932.

- Halbert, Henry; Ball, Timothy (1895). The Creek War of 1813 and 1814. Chicago, Illinois: Donohue & Henneberry. ISBN 9781375702775.

- Harris, W. Stuart (1977). Dead Towns of Alabama. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0-8173-1125-4.

- Owen, Thomas McAdory, ed. (1898). Transactions of the Alabama Historical Society. Vol. II. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: Alabama Historical Society. ISBN 978-0267708888.

- Pickett, Albert James (1878). History of Alabama, and Incidentally of Georgia and Mississippi, from the Earliest Period. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: Willo Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1363310845.

- Rowland, Dunbar, ed. (1921). Publications of the Mississippi Historical Society: Centenary series. Vol. IV. Jackson, Mississippi: Mississippi Historical Society. ISBN 978-0526689989.