Fort Saint-Louis (Texas)

Fort Saint-Louis, Texas, was founded in 1685 by French explorer René-Robert Cavelier de La Salle and members of his expedition, including Jesuit missionary Zenobius Membre, on the banks of Garcitas Creek, a few kilometers inland from the mouth of the Lavaca River. La Salle had intended to establish the colony at the mouth of the Mississippi, but inaccurate charts and navigational errors led his ships more than six hundred kilometers to the west, to the coast of Texas.

| 28°20′N 97°07′W | |

| Location | United States Texas |

|---|---|

| Completion date | 18th century |

| Initial destination | Military fort |

The colony's brief existence was fraught with difficulties, including the hostility of the natives, epidemics and harsh climatic conditions. Conscious of his original mission, La Salle led several expeditions to find the Mississippi, which enabled him to explore much of the Río Grande and eastern Texas. During one of his absences, in 1686, the colony's last ship was destroyed, prohibiting the colonists from obtaining supplies from French possessions in the Caribbean Sea. His last expedition took place on the Brazos River in early 1687. It was then that La Salle and five of his men were murdered, due to rivalries within the group he was leading.

Spain heard of La Salle's mission in 1686. Worried that a French colony might threaten their possessions in New Spain, the Spanish authorities launched several expeditions to discover and destroy it. A Spanish expedition led by Alonso de León finally came upon the remains of the fort in the spring of 1689, three or four months after the Karankawas people had killed most of the French, with the exception of five children whom they captured. Although it only existed for three years, this colony enabled France to claim possession of Texas, and later the United States to justify its claim to Spanish Texas, on the pretext that it was part of the territory involved in the Louisiana Purchase.

Context

By the end of the 17th century, much of North America was occupied by European countries. Spain possessed Florida, Mexico and most of the southwest of the continent (Spanish Texas). The North Atlantic coast was in British hands, and the French occupied New France, much of what is now Canada, as well as the Illinois Country. The French feared that their territory was vulnerable to the expansionist aims of their neighbors. In 1681, Robert de La Salle launched an expedition down the Mississippi, hoping to reach the Pacific Ocean,[1] but in fact discovered a route leading to the Gulf of Mexico. Although Hernando de Soto had explored and taken possession of this region for Spain one hundred and forty years earlier,[2] on April 9, 1682, La Salle claimed the Mississippi Valley on behalf of the King of France, Louis XIV, and named it Louisiana, in his honor.[3]

Without the French presence at the mouth of the Mississippi, Spain would control the entire Gulf of Mexico and pose a threat to the southern borders of New France.[4] La Salle considered the Mississippi to be close to the eastern tip of New Spain, and on his return to France in 1683, he proposed the creation of a colony at the river's mouth. This would provide a base for promoting Christianity among the native peoples, as well as an ideal bridgehead for attacking the Spanish province of Nueva Vizcaya and gaining control of its rich silver mines.[2][5] He argued that a small number of Frenchmen could succeed in invading New Spain through an alliance with the native peoples, angry at being enslaved by the Spanish.[2] After Spain declared war on France in October 1683, Louis XIV agreed to support La Salle's plan;[2] his official duties from then on included "confirming the allegiance of the Indians to the crown of France, which would lead them to the true faith, and maintaining inter-tribal peace."[5]

The expedition

La Salle's original plan was to sail to New France, then overland to the Illinois Country and down the Mississippi to its mouth.[6] However, Louis XIV instructed La Salle to sail across the Gulf of Mexico, which Spain considered its exclusive property.[7] Although La Salle had requested only one ship, on July 24, 1684, he left La Rochelle with four vessels: the 36-gun man-of-war, Le Joly, the 300-ton supply ship, L'Aimable, the three-masted ship, La Belle, and the ketch, Saint-François.[8][9][10] Although Louis XIV supplied Le Joly and La Belle, La Salle, who wanted more cargo space, leased L'Aimable and Saint-François to French merchants. The king also provided one hundred soldiers and the entire crews of the ships, as well as funds to hire skilled workers to join the expedition. However, La Salle was obliged to use his own funds to purchase goods for exchange with the Amerindians.[11]

The ships carried nearly 300 people, including soldiers, craftsmen, six missionaries, eight merchants and more than a dozen women and children.[12] Shortly after their departure, France and Spain ceased hostilities, and Louis XIV showed little interest in sending reinforcements to La Salle.[10] Details of the voyage were kept secret, so that Spain was unaware of its purpose, and La Salle's naval officer, Sieur de Beaujeu, was furious at not having been informed of their destination until after their departure. Discord between them intensified when they arrived in Saint-Domingue and quarreled over where to anchor. Beaujeu set sail for another part of the island, allowing the Spanish privateers to seize the Saint-François, fully loaded with provisions and tools for the colony.[13]

During the 58-day voyage, two people died of illness and one woman gave birth to a child.[14] The journey to Santo Domingo took longer than expected, and provisions were rather limited, especially after the loss of the Saint-François. La Salle had little money to replenish supplies, but two of the merchants on board had sold some of their goods to the islanders, and lent their profits to La Salle. To fill the gaps left by the desertion of several men, La Salle recruited a few islanders to join the expedition.[15]

At the end of November 1684, when La Salle had just recovered from a severe illness, the three ships set off in search of the Mississippi delta.[13] Before they left Santo Domingo, local sailors warned them that the Gulf's powerful currents could push their ships back towards the Florida Straits, if they did not correct their course.[16] On December 18, the expedition reached the Gulf of Mexico, entering territory that Spain claimed as its own.[17] None of the members of the expedition had ever sailed the Gulf or known its coasts.[18] Due to inaccurate charts, a miscalculation by La Salle in determining the latitude of the mouth of the Mississippi,[16] and an exaggerated correction for currents, the expedition was unable to find the Mississippi. It landed in Matagorda Bay in early 1685, over six hundred kilometers west of the river.[16]

Fort construction

On February 20, the colonists disembarked for the first time since leaving Santo Domingo three months earlier. They set up a temporary camp on the site of today's Matagorda lighthouse.[19] The expedition's chronicler, Henri Joutel, described his first impression of Texas as follows: "The country did not seem very favorable to me. It was flat and sandy, but nevertheless covered with grass. There were several small salt lakes. We didn't see much wild fowl, except for a few sandhill cranes and geese that weren't expecting us.[20]

Against Beaujeu's advice, La Salle ordered La Belle and L'Aimable "to negotiate the narrow and shallow pass" to bring supplies closer to camp.[21] To lighten L'Aimable's load, its eight cannons and a small part of its cargo were unloaded. After La Belle had successfully negotiated the pass, La Salle sent his pilot to L'Aimable to help with the navigation, but L'Aimable's captain refused.[20][22] As L'Aimable set sail, a group of Karankawas Amerindians approached and kidnapped some of the colonists. La Salle took a small group of soldiers to rescue them.[23] When he returned, L'Aimable was stranded on a sandbank.[19] After learning that the captain had given the order to sail even though his ship had hit the shoal, La Salle was convinced that the captain had deliberately beached his ship.[24]

For several days, the men tried to salvage tools and provisions from L'Aimable, but a storm prevented them from saving more than a few cannons, gunpowder, some food and goods before the ship sank on March 7.[21] The Karankawas then plundered the remains of the shipwreck, which washed ashore. When French soldiers approached their village to take back their possessions, the natives went into hiding. Discovering the village deserted, the soldiers recovered the goods, but also stole some furs and two canoes. The furious Karankawas then attacked, killing two Frenchmen and wounding several others.[21]

Beaujeu, having accomplished his mission of escorting the colonists across the Atlantic Ocean, returned to France aboard the Joly in mid-March 1685.[25][26] Many of the colonists chose to leave with him,[27] leaving only a group of 180.[28] Although Beaujeu delivered a message from La Salle on his arrival requesting more provisions, the French authorities, now at peace with Spain, never responded.[10][29] Among the remaining colonists, those suffering from dysentery and venereal disease gradually died.[25] The healthy built wells and a temporary fort on the island of Matagorda.[28]

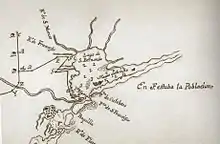

On March 24, La Salle took 52 men in five canoes to find a less exposed site. They discovered Garcitas Creek, a fish-filled river with fertile banks. They named it Rivière aux Bœufs after the bison that grazed nearby. Fort Saint Louis was built on a promontory overlooking the river, a league and a half from its mouth. Two men died, one bitten by a rattlesnake and the other drowning while fishing.[28] Sometimes at night, the Karankawas surrounded them and howled, but the soldiers managed to scare them off with a few shots.[30]

In early June, La Salle led the remaining settlers to the newly-discovered site. Seventy people embarked on an 80-kilometer overland journey on June 12. All provisions and goods were unloaded from La Belle, a back-breaking task that was completed by mid-July. The last load was taken away by the 30 men who had guarded the ship until then.[30] Although trees were growing near the new site, they were not suitable for building a fort, and logs had to be transported several kilometers to the construction site. Some of the beams and planks salvaged from L'Aimable were also transported.[29] By the end of July, half the settlers had died of exhaustion and starvation.[30]

The survivors build a large two-storey building in the center of the site. The first floor was divided into three rooms, one for La Salle, one for the priests and one for the officers.[29] The second floor featured a single room for storage. Surrounding the building were several other, smaller rooms housing the other members of the expedition. The eight cannons rescued from L'Aimable, each weighing between 318 and 514 kg, were positioned around the fort.[31]

Explorations

For several months, the colonists led short expeditions to explore the surroundings of their new domain. At the end of October 1685, La Salle decided to lead an expedition further afield with his only remaining ship, La Belle. He resupplied the ship and took on board 50 men in addition to La Belle's 27-man crew, leaving 34 men, women and children at the fort. The main body of the crew accompanied La Salle in canoes along the coast, while La Belle followed further out to sea. After a three-day voyage, they came upon a village of hostile Amerindians. Twenty Frenchmen attacked the native village, where they found various Spanish artefacts.[32] Several men died from eating Barbary figs, and the Karankawas killed a small group camping on the beach, including La Belle's captain.[33]

From January to March 1686, La Salle and his men set out overland to find the Mississippi: they headed west to the Rio Grande, probably reaching the present-day town of Langtry.[33][34] The men questioned the natives, asking them about the situation of the Spaniards and their mines, offering them gifts and telling them stories depicting the Spaniards as cruel and the French as benevolent.[10] When the group returned, they were unable to find La Belle[N 1] and were forced to walk back to the fort.[33][34]

The following month, they search eastward for the Mississippi River and returned to Canada.[34] Along the way, they meet the Caddos, who gave them a map of their territory, that of their neighbors, and showing the position of the Mississippi.[35] The Caddos were accustomed to making friendly pacts with their neighbors, and extended this peaceful policy to the French.[36] Among the Caddos, the expedition met Jumanos traders, who reported the presence of the Spanish in what is now New Mexico. These merchants would later inform the Spanish of their encounter with the French.[37]

When they reached the Neches River, four men deserted, and La Salle and one of his nephews fell ill, forcing the group to stop for two months. When they recovered, food and gunpowder began to run out.[35] In August, the eight survivors of the expedition[35] returned to Fort Saint Louis, having never gone beyond what is now eastern Texas.[38]

While La Salle was underway, six of the sailors who had been on La Belle arrived at Fort Saint Louis. According to their accounts, La Belle's new captain was a drunkard, perpetually inebriated. Few of the sailors were able to navigate, and the ship ran aground on the Matagorda peninsula. The survivors returned by canoe to the fort, leaving the ship behind.[39] The destruction of their last ship left the colonists isolated on the Texas coast, with no hope of reaching the French Caribbean colonies.[25]

By early January 1687, fewer than 45 of the 180 people in the colony remained, and the colony was plagued by internecine warfare.[38][40][41] La Salle believed their only hope of survival was an overland expedition to New France,[39] so he launched an expedition to the Illinois Country.[38] Fewer than 20 colonists remained at Fort Saint Louis, mainly women, children and the sick, along with seven soldiers and three missionaries, with whom La Salle was displeased.[40] Seventeen men took part in the expedition, including La Salle, his brother and two of his nephews. While camped near present-day Navasota on March 18, the men quarreled over a piece of bison meat. During the night, one of La Salle's nephews and two other men were murdered in their sleep by a member of the expedition. The next day, La Salle was killed while investigating his nephew's disappearance.[38][42] A fight ensued, which led to the death of two other members of the expedition.[43] Two of the survivors, including Jean L'Archevêque, joined the Caddos. The remaining six managed to reach the Illinois country. During their journey from Illinois to Canada, the men tell no one that La Salle had died. They returned to France in the summer of 1688, and informed the King of La Salle's death and the terrible conditions in the colony, but Louis XIV sent no help.[44]

Spanish response

La Salle's mission remained secret until 1686, when Denis Thomas, a member of the expedition who had deserted Saint-Domingue, was arrested for piracy. Hoping for a lighter sentence, Thomas informed his Spanish jailers of La Salle's plans to found a colony and eventually seize the silver mines. Despite his confession, Thomas was hanged.[45]

The Spanish government realized that the French colony was a threat to their mines and shipping routes, so Carlos II's council of war felt that "Spain had to take swift action to remove this thorn that was piercing the heart of America. The longer we wait, the more difficult it will be."[10]. The Spanish had no idea of La Salle's whereabouts, and in 1686 they sent one sea expedition and two land expeditions to try to discover his colony. Although the expeditions failed to find La Salle, they did determine that he had to be located between the Rio Grande and the Mississippi.[46] The four other expeditions launched the following year were also unsuccessful, but enabled Spain to gain a better understanding of the geography and coastline of this part of the Gulf of Mexico.[46]

In 1688, the Spanish sent three new expeditions, two by sea and one by land. The land expedition, led by Alonso de León, discovered Jean Gery, who had deserted the French colony and was living with Coahuiltecans in what is now southern Texas.[47] Using Gery as a guide and translator, De León finally found the fort at the end of April 1689.[48] The fort and the five surrounding buildings were in ruins.[34] A few months earlier, the Karankawas had attacked the colony. The natives wreaked death and destruction, and the bodies of three people were found, including a woman who had been shot in the back with an arrow.[48] A Spanish priest accompanying De León organized a funeral service for the three victims.[34] The expedition's chronicler, Juan Bautista Chapa, wrote that all this was divine retribution for opposing the Pope, as Alexander VI had granted the territory of the Indies to the Spaniards alone.[49][48][50] They burned what remained of Fort Saint Louis, no doubt with the aim of erasing all traces of the French presence. The Spaniards also buried the eight French cannons, no doubt intending to return for them later.[51] They did indeed return to establish their own presidio (fort) on this site in 1722, but the cannons were not found.

Early in 1689, the Spanish authorities received a letter written in French. Jumanos scouts received these papers from the Caddos, who asked them to hand them over to the Spaniards. The documents included a painting on parchment depicting a ship, as well as a message written by Jean L'Archevêque. The message read:

I don't know what kind of people you are. We are French [;] we live among savages[;] we would prefer to be among Christians such as ourselves[.] ... Our only grievance is to be among beasts like them who believe neither in God nor in anything. My Lords, if it pleases you to take us, all you have to do is send us a message. ... We will deliver ourselves to you.[50]

Some time later, De León rescued L'Archevêque and his companion Jacques Grollet. When questioned, they mention that over 100 settlers had died of smallpox, and that the rest had been killed by natives.

Posterity

There were only fifteen survivors of the colony founded by La Salle. Six returned to France, the others were captured by the Spanish.[38] De León found four children, survivors of the final Amerindian attack, who were adopted by the Karankawas.[52] According to the children's testimony, they were attacked around Christmas 1688, and all the settlers were killed.[50] After their rescue, they were entrusted to the Viceroy of New Spain, Count of Galve, where they became servants. Among them were brothers Pierre and Jean-Baptiste Talon, who also returned to France and whose testimony was used for Iberville's 1699 expedition to the Gulf of Mexico.[52] Among the other Spanish captives, three became Spanish citizens and settled in New Mexico.[38] Despite the destruction of the French colony, the Spanish feared that a return attempt by the French was inevitable. For the first time, the Spanish crown authorized the installation of outposts in East Texas and Pensacola.[51]

France did not relinquish its claim to Texas until November 3, 1762, when it ceded all territory west of the Mississippi to Spain under the Treaty of Fontainebleau.[53] In 1803, three years after Spain had returned Louisiana to France, Napoleon sold it to the United States. The original treaty, between Spain and France, did not explicitly define Louisiana's borders, and the descriptions contained in the document are ambiguous and contradictory.[54] The United States insisted to Spain that the sale included all the territory claimed by France, including Texas.[54] The matter was not settled until February 22, 1819, when Spain ceded Florida to the United States, in return for which the latter relinquished its claim to Texas. The official border of Texas was placed on the Sabine River (the present-day border between Texas and Louisiana), then following the Southern Red and Arkansas rivers to the 42nd parallel.[55]

Archaeological excavations

In 1908, historian Herbert Eugene Bolton identified a site along Garcitas Creek, near Matagorda Bay, as the location of the fort. Other historians, before and after Bolton, placed it on Lavaca Bay.[56] Historians and archaeologists debated the exact location of Fort Saint-Louis for several decades, with some casting doubt on whether the Spaniards had built their presidio on its ruins as they claimed. In 1950, archaeological excavations at the Garcitas Creek site near the Texas Memorial Museum uncovered traces of the Spanish fort and numerous artifacts of French origin. However, the French cannons were never found,[56][57] a doubt that was removed when a farmer found them with a metal detector on the Garcitas Creek site. In 1996, archaeologists from the Texas Historical Commission (THC) were commissioned to excavate and document the site where the eight well-aligned cannons, which had not seen the light of day for 300 years, rested.[56][58]

This discovery put an end to the historical debate over the fort's location and led to extensive research into Fort St. Louis and the presidio by the THC. Under the direction of Dr. Jim Bruseth and the assistance of project manager Mike Davis, THC archaeologists excavated the site until 1999. They mapped the locations of the fort and presidio, and learned new details about the two periods of occupation. One of the most important discoveries was that of the graves of the three Frenchmen buried by the Spaniards.[58]

For decades, THC has also been searching for the site of La Belle's shipwreck. In 1995, it was discovered in Matagorda Bay. Researchers brought to the surface a 363 kg bronze cannon, as well as musket balls, bronze brooches and barter beads.[59] Large sections of the wooden hull were intact, protected from the warm salt water by layers of muddy sediment that had created an oxygen-free gangue around the wreck.[59][60] La Belle was the oldest French shipwreck found in the Western Hemisphere. To enable archaeologists to recover as many artifacts as possible, a cofferdam was built around the wreck. This allowed the scientists to work in the dry, as if they were on dry land. This was the first attempt of its kind in North America. Research using a cofferdam had been carried out in Europe, but none on a vessel as large as La Belle.[61]

The National Underwater and Marine Agency searched for the wreck of L'Aimable from 1997 to 1999. Although a promising site was found, the ship was lying under more than seven meters of sand and could not be reached.[62]

See also

Notes

- Archaeologists from the Texas Historical Commission (THC) discovered a skeleton in the wreck of La Belle during an excavation in 1996. Near the skeleton, on a roll of rope, was a pewter cup inscribed "C. Barange", and a small water barrel. Archaeologists know from historical documents that La Belle's crew had run out of drinking water while awaiting La Salle's return, and they believe that the sailor probably died of thirst before the ship sank. The French sailor's remains were buried in the Texas State Cemetery on February 3, 2004. The THC organized the event, which was attended by the French Ambassador to the United States..

References

- Bannon 1997, p. 94.

- Weber 1992, p. 148.

- Chipman 1992, p. 72.

- Chipman 1992, p. 73.

- Calloway 2003, p. 250.

- Bruseth & Turner 2005, p. 76.

- Bruseth & Turner 2005, p. 19.

- Weddle 1991, p. 13.

- Chipman 1992, p. 74.

- Weber 1992, p. 149.

- Bruseth & Turner 2005, p. 20.

- Weddle 1991, p. 13, 16.

- Chipman 1992, p. 75.

- Weddle 1991, p. 16.

- Weddle 1991, p. 17.

- Chipman 1992, p. 76.

- Weddle 1991, p. 19.

- Weddle 1991, p. 20.

- Weddle 1991, p. 23.

- Bruseth & Turner 2005, p. 23.

- Weddle 1991, p. 24.

- Henri Joutel (1713), p. 72.

- Henri Joutel (1713), p. 73.

- Bruseth & Turner 2005, p. 26.

- Chipman 1992, p. 77.

- Henri Joutel (1713), p. 94.

- Weddle 1991, p. 25.

- Weddle 1991, p. 27.

- Bruseth & Turner 2005, p. 27.

- Weddle 1991, p. 28.

- Bruseth & Turner 2005, p. 28.

- Weddle 1991, p. 29.

- Weddle 1991, p. 30.

- Chipman 1992, p. 83.

- Weddle 1991, p. 34.

- Calloway 2003, p. 252.

- Calloway 2003, p. 253.

- Chipman 1992, p. 84.

- Weddle 1991, p. 31.

- Weddle 1991, p. 35.

- Henri Joutel (1713), p. 157.

- Henri Joutel (1713), p. 201.

- Weddle 1991, p. 38.

- Bannon 1997, p. 97.

- Bruseth & Turner 2005, p. 7-8.

- Weber 1992, p. 151.

- Weber 1992, p. 151-152.

- Weber 1992, p. 152.

- Voir l'article Traité de Tordesillas.

- Calloway 2003, p. 255.

- Weber 1992, p. 153.

- Calloway 2003, p. 256.

- Weber 1992, p. 198.

- Weber 1992, p. 291.

- Weber 1992, p. 299.

- Allan Turner (16 February 1997). "Cannons' discovery ends debate on LaSalle fort". Houston: Houston Chronicle. p. City and State, 2. Retrieved 11 July 2007..

- Bruseth & Turner 2005, p. 32.

- "Fort St. Louis Excavation Highlights". Texas Historical Commission. Retrieved 9 September 2008..

- Allan Turner (14 July 1995). "History surfaces in Matagorda Bay". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 7 November 2007..

- Allan Turner (30 July 1995). "History rising from the bay's murky depths: La Salle ship one of many Matagorda victims". Houston Chronicle. p. State section, page 1. Retrieved 7 November 2007..

- Bruseth & Turner 2005, p. 48.

- Bruseth & Turner 2005, p. 45.

Bibliography

- Bannon, John Francis (1997). The Spanish Borderlands Frontier, 1513–1821. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-0309-7..

- Bruseth, James E.; Turner, Toni S. (2005). From a Watery Grave: The Discovery and Excavation of La Salle's Shipwreck, La Belle. College Station: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-58544-431-1..

- Calloway, Colin G. (2003). One Vast Winter Count: The Native American West Before Lewis and Clark. History of the American West. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-1530-6..

- Chipman, Donald E. (1992). Spanish Texas, 1519–1821. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-77659-3..

- Chaline, Olivier (2016). La mer et la France: Quand les Bourbons voulaient dominer les océans. Au fil de l’histoire (in French). Paris: Flammarion. ISBN 978-2-0813-3327-7..

- Vergé-Franceschi, Michel (2002). Dictionnaire d'Histoire maritime. Bouquins (in French). éditions Robert Laffont. ISBN 2-221-08751-8..

- Joutel, Henri (1713). Journal historique du dernier voyage que feu M. de La Sale fit dans le golfe de Mexique, pour trouver ... la riviere de Missicipi (in French). Paris: Chez E. Robinot. OCLC 166613126..

- du Terrage, Marc Villiers (1931). L'expédition de Cavelier de La Salle dans le golfe du Mexique (1684–1687) (in French). Paris: A. Maisonneuve. OCLC 221608557..

- Weber, David J. (1992). The Spanish Frontier in North America. Yale Western Americana Series. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-05198-8..

- Weddle, Robert S. (1991). The French Thorn: Rival Explorers in the Spanish Sea, 1682–1762. College Station: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-0-89096-480-4..

- Ifremer, L'épave de La Belle : accord Franco-Américain (in French), 2003.

- Texas Beyond History, Fort Saint-Louis, texasbeyondhistory.net, 2005.

- Texas Historical Commission (THC), La Salle Shipwreck Project, thc.state.tx.us.

External links

- 19 mars 1687 : Mort tragique de Cavelier de la Salle (in French) On Hérotode.

- La Salle's Texas Settlement on the Handbook of Texas Online website.

- Fort St. Louis Archeological Project on the Texas Historical Commission website.

- Fort St. Louis on the Texas Beyond History website.