Fort Vause

Fort Vause (also known as Fort Vaux, Voss, Vass, Vance, or "Vass' Fort", and renamed Fort Lyttelton in 1757) was built in 1753 in Montgomery County, Virginia, by Ephraim Vause. The historic site is near the town of Shawsville, Virginia. It was attacked by French troops and Native American warriors in 1756, and most of the inhabitants were killed or taken prisoner.[1]: 151–56 The fort was rebuilt in 1757 but abandoned by 1759.

| Fort Vause | |

|---|---|

| Montgomery County, Virginia, USA | |

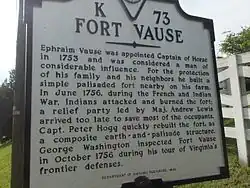

1998 state historical marker near Shawsville | |

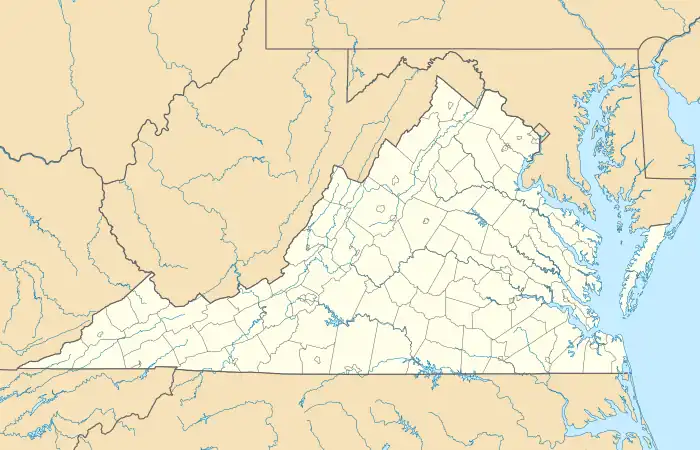

Fort Vause Approximate location of Fort Vause in Virginia | |

| Coordinates | 37°10.312′N 80°15.83′W |

| Type | Fort |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by | Privately owned land |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1753 |

| In use | 1753-1758 |

| Battles/wars | French and Indian War |

| Garrison information | |

| Past commanders | Captain John Smith Captain Peter Hogg Captain Henry Woodward |

| Garrison | 25-170 troops |

| Designated | 1998 |

History

The original fort was built in 1753 on the Great Wagon Road leading from Philadelphia to North Carolina,[2]: 43 to protect the home of Ephraim Vause and his neighbors. There is no description of the fort, but privately-built fortified homesteads of this period were typically stockades surrounding the farmhouse and outbuildings, in some cases including a crude two-storey blockhouse. Between 17 and 25 Virginia militia troops were stationed there in 1756, under the command of Captain John Smith.[3]: 124

Mary Draper Ingles and her husband William Ingles took refuge in the fort after their home was attacked during the Draper's Meadow Massacre of July, 1755, in which Mary and her sons were taken prisoner. Mary escaped and returned to her husband, and in early 1756 they moved to Fort Vause. Soon after their arrival, however, Mary had a pre-sentiment that the fort would be attacked, and asked her husband to leave.[4]

They left on 25 June,[5]: 93–94 and later the same day Fort Vause was attacked by 25 French soldiers together with 205 Miami, Ottawa and Shawnee warriors[2]: 43 [6]: 13 under the command of François-Marie Picoté de Belestre.[2]: 43 John and Matthew Ingles, younger brothers of William, chose to remain at the fort after William decided to leave with Mary. John is credited with shooting a scout from a tree, and then sounding the alarm that the fort was about to be attacked. He was killed and his wife Mary and their children were taken prisoner.[7]: 401 Matthew was out hunting at the time and was attacked on his way home. He fought hand-to-hand until his rifle broke, then with a frying pan handle, killing two of his attackers. He was taken prisoner by the Shawnee, but several years later was released or escaped. He died at Ingles Ferry, "a few months after his return."[1]: 115 [8]: 443–447 [5]: 93–94

George Washington wrote that a lack of vigilance by the sentries may have allowed the attackers to launch a surprise assault: "Indolent and careless, and always unguarded, [the sentries] are liable to be surprized. By this means Vass’s Fort was taken (and the Garrison destroyed)."[9] However, the fort's commander, Captain John Smith, was able to send a message to Captain William Preston requesting help.[10]: 49–51 One source says the 17 defenders held off the attackers for three days,[11] whereas another source says the siege lasted only 8 hours, during which 32 of the attackers were killed.[12]: 12 The French commander Belestre was also wounded during the siege.[13] Eventually only three men were still able to fight,[14]: 396 and their ammunition gave out, at which point the garrison surrendered on condition that they be permitted to leave.[7]: 398

Aftermath

At least 3 settlers were killed, and 22 were taken prisoner, including Ephraim Vause's wife, daughters, a slave and two servants (Ephraim was away on the day of the attack).[1]: 155–56 The fort was burned[15] and Shawnee warriors tortured and burned one of the fort's soldiers, a man named Cole.[16]: 95–96 [14]: 193, 201 Two other prisoners were killed, a badly wounded soldier and an elderly man.[12]: 12 The other prisoners were taken down the Mississippi River to New Orleans, after which several of them were then sent to Detroit and eventually transported to France, including the fort's commander, Captain John Smith. He was sent to England in an exchange of prisoners and returned to Virginia in early 1758.[7]: 399 Ephraim Vause's daughter Elizabeth Levicee Vause was held prisoner until she was released by agreement with Colonel Henry Bouquet in 1763.[10]: 49–51

A relief expedition of 47 men led by Major Andrew Lewis and Captain William Preston arrived on 26 June,[15] too late to aid the pioneers.[17] On 5 June, 1757, Cherokee warriors defending Fort Cumberland on the Maryland-Virginia border captured the French commander Belestre, who had been leading raids against other English settlements.[18][2]: 46 Ephraim Vause left the Shenandoah Valley in 1757 after a failed attempt to rescue his wife, and sold off his land in 1760.[19][20]: 361

Peter Looney

One prisoner, a 23-year-old sergeant named Peter Looney (or Lewney), was taken by Shawnees to Lower Shawneetown in Ohio.[14]: 201 He was then sent to Detroit, where he was adopted by a Native American family.[21] He became a respected warrior and attended important diplomatic meetings with the French.[22]: 172 He later escaped from his captors at Niagara, New York and reached Albany on 12 July, 1757.[12]: 12–13 He traveled to Philadelphia and then returned to Virginia, reporting on the fate of Captain Smith.[16][15]

Rebuilding

Construction on a new fort was initiated by Captain Peter Hogg in 1756 as an earthworks and palisade construction.[23] On 27 July 1756, Governor Robert Dinwiddie wrote orders on the fort's design: "It is agreed that...Fort Vaus be made at least one hundred feet Square in the Clear and that the Stockades be at least 14 feet Long."[24] When completed, it was a 100-foot square four-bastioned earthwork with a 15-foot high log palisade, with barracks.[19]

The fort was to be garrisoned with 100 men,[25] although George Washington recommended 150.[3]: 129 He visited the construction site in October 1756, as part of his tour of inspection of Southwestern Virginia.[17] Washington wrote to Governor Dinwiddie that "Vass’s place is a pass of very great importance, being a very great inroad of the enemy, and secure, if it was strongly garrisoned."[26] He noted in a November, 1756 proposal for the construction of frontier forts that "The fort at Vass’s, (which Capt. Hogg is now building) is in a much-exposed gap, subject to the inroads of the southern Indians."[27] The garrison was increased by an additional 70 men in May, 1757.[28]

Construction was delayed several times. Tools were difficult to obtain and they wore out quickly. The 30-man construction crew was paid sixpence per day, but in July 1756 they demanded an additional payment of 40 pounds of tobacco daily, which Washington refused to consider. Construction was still incomplete as of July 1757, and Washington was dissatisfied with the fort's location, writing to Hogg: "I have great complaints concerning your manner of carrying on the works at the Fort you are building. It has cost infinitely more money than ever was intended for it, and, by the injudicious spot of ground you have chosen to fix it upon, it has caused a general clamour."[29] Washington replaced Captain Hogg with Lieutenant Thomas Bullitt, sending Captain Henry Woodward to supervise construction.[3]: 128 Washington wrote to Woodward:

- "As the Fort which Captn Hogg is building, and to which you are now going, has, either thro' bad conduct in the Director, idleness in the workman, or through some other cause which I can not comprehend, been of infinitely more expense to the country, and much longer about, than was ever expected–-You are required to finish it with the utmost dispatch; and in that in any manner, however rough, if it will secure you upon an attack."[30]

Construction was completed by mid-August, at which point the fort was renamed Fort Lyttelton. By 1 September, Colonel Andrew Lewis reduced the garrison to one officer and twenty men, but records for February 1758 show a garrison of 74 men and 8 officers.[3] : 129

There is no mention of Fort Vause in colonial records after 1758, suggesting that it was abandoned, or possibly just used for storage.[3]: 129

Archaeological excavations

The Fort Vause Archaeological Site was established in 1968. Archaeological test excavations undertaken in 1968 identified the location and general size of the second fort[23] as well as evidence of its predecessor.[17][31] Excavations in 2005-2006 located three bastions of the second fort, still visible today.[19] Artifacts uncovered during these excavations included wrought-iron nails, clay pipe stems, British Brown stoneware, salt-glazed stoneware, a cast-iron kettle fragment, a gunflint, lead musket balls of several different calibers, and glass bottle fragments.[3]: 130–38 The site is now on the property of the Hinshelwood family.[32]

Legacy

Fort Vause is a National Landmark, file #060-0017.[17] A brass plaque mounted on a stone plinth was placed at the fort's site on 2 December, 1969.[17]

A replica of the fort was built at the Explore Park in Roanoke County, Virginia in 2004.[19][33]: 13 [34]

External links

References

- Waddell, Joseph Addison. Annals of Augusta County, Virginia, from 1726 to 1871. Virginia Historical Society, Staunton VA: C. R. Caldwell, 1902.

- Douglas McClure Wood, "I Have Now Made a Path to Virginia": Outacite Ostenaco and the Cherokee-Virginia Alliance in the French and Indian War," West Virginia History, New Series, Vol. 2, No. 2 (FALL 2008), pp. 31-60. West Virginia University Press

- Lawrence Babits, Stephanie Gandulla, eds. The Archaeology of French and Indian War Frontier Forts. University Press of Florida, 2013.

- Transcript of John Ingles' manuscript "The Narrative of Col. John Ingles Relating to Mary Ingles and the Escape from Big Bone Lick" Archived 2012-03-13 at the Wayback Machine, 1824.

- Hale, John P. Trans-Allegheny Pioneers (West Virginia and Ohio): Historical Sketches of the First White Settlers West of the Alleghenies, 1748 and After. 1886, reprinted 2002.

- Darby O’Donnell, Phase I Cultural Resource Identification Survey of Proposed Mountain Bike Trails and Parking Lot at Explore Park, Roanoke County, Virginia, Darby O’Donnell LLC, October 28, 2018

- Joseph A. Waddell, "Indian Wars in Augusta County," in The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Volume 2, Philip Alexander Bruce, William Glover Stanard, editors. Virginia Historical Society, 1894

- Pendleton, William Cecil. History of Tazewell County and Southwest Virginia: 1748-1920, W. C. Hill Printing Company, 1920.

- "From George Washington to John Campbell, Earl of Loudoun, 10 January 1757," Founders Online, National Archives. The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 4, 9 November 1756 – 24 October 1757, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1984, pp. 79–93.

- Patricia Givens Johnson, William Preston and the Allegheny Patriots, B. D. Smith & Bros., 1976 ISBN 0961476559

- Beverley Bond, "The Captivity of Charles Stewart, 1755-57," in The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Volume 13, June 1926-March 1927, Mississippi Valley Historical Association, 1927; pp 58-200

- Daniel P. Barr, The Boundaries Between Us: Natives and Newcomers Along the Frontiers of the Old Northwest Territory, 1750-1850. Kent State University Press, 2006.

- Maass, John R. George Washington's Virginia. Arcadia Publishing, 2017.

- Steele, Ian K. Setting All the Captives Free: Capture, Adjustment, and Recollection in Allegheny Country. Canada: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2013.

- "To George Washington from Robert Dinwiddie, 12 July 1756," Founders Online, National Archives. The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 3, 16 April 1756–9 November 1756, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1984, pp. 259–261.

- Milo M. Quaife, "The Captivity of Peter Looney." The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Volume 15, 1928-1929

- "Fort Vause," Virginia Department of Historic Resources, June 2, 2023

- "From George Washington to John Stanwix, 15 June 1757," Founders Online, National Archives. Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 4, 9 November 1756 – 24 October 1757, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1984, pp. 215–217.

- Pete Payette, "Frontier Forts of Southwest Virginia," American Forts Network, 2009.

- Chalkley, Lyman. Chronicles of the Scotch-Irish Settlement in Virginia: Extracted from the Original Court Records of Augusta County, 1745–1800, vol III The Commonwealth Printing Company, Rosslyn VA, 1912.

- Patricia H. Quinlan, The Story of Peter Looney: His Year Living with the Indians, iUniverse, 2009 ISBN 1440131961

- Matthew C. Ward, "Redeeming the Captives: Pennsylvania Captives among the Ohio Indians, 1755-1765," The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, July 2001, Vol. 125, No. 3, University of Pennsylvania Press; pp. 161-189

- Mcbride, Kim A., "The Second Fort Vause: A Crucial French and Indian War Fort in the Roanoke Valley of Virginia," in Lawrence E. Babits, and Stephanie Gandulla (eds), The Archaeology of French and Indian War Frontier Forts Gainesville, FL, 2013; online edn, Florida Scholarship Online, 29 May 2014. Accessed 1 Sept. 2023.

- "From George Washington to Robert Dinwiddie, 4 August 1756," Founders Online, National Archives. The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 3, 16 April 1756–9 November 1756, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1984, pp. 312–323.

- "From George Washington to Robert Dinwiddie, 2 April 1757," Founders Online, National Archives. The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 4, 9 November 1756 – 24 October 1757, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1984, pp. 126–128.

- "From George Washington to Robert Dinwiddie, 10 October 1756," Founders Online, National Archives. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 3, 16 April 1756–9 November 1756, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1984, pp. 430–435.

- "Enclosure: Proposal for Frontier Forts, 9 November 1756," Founders Online, National Archives. The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 4, 9 November 1756 – 24 October 1757, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1984, pp. 10–11.

- "To George Washington from Robert Dinwiddie, 16 May 1757," Founders Online, National Archives. The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 4, 9 November 1756 – 24 October 1757, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1984, pp. 153–156.

- "From George Washington to Peter Hog, 24 July 1757," Founders Online, National Archives. The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 4, 9 November 1756 – 24 October 1757, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1984, pp. 325–327.

- "From George Washington to Henry Woodward, 29 July 1757," Founders Online, National Archives. The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 4, 9 November 1756 – 24 October 1757, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1984, pp. 350–351.

- Virginia Dept. of Historical Resources. 1999. The Virginia Landmarks Register. Page 320.

- Key, Lindsay. 2006. "Shawsville students help on archaeological dig" Roanoke Times. May 23, 2006.

- Alfred C. Anderson, "Report of the Virginia Recreational Facilities Authority: Virginia's Explore Park, Chapter 279 and Chapter 731," (2010)

- Photos of the Fort Vause replica at Explore Park in Roanoke, Virginia, by Pat and Chuck Blackley