Fort de Valros

The Fort de Valros (also known locally as Tour de Valros) is a ruined small castle or fortress in the commune of Valros in the Hérault département of France. In the mid-19th century, the fort was the site of a semaphore station.

History

The site has no visible trace of occupation from antiquity, but archaeological digs have uncovered the remains of a necropolis used from the 8th to the 10th century.[1]

The promontory on which the fort stands is a strategic observation post. At 100 m altitude, it dominates the valley of the Thongue and controls two very ancient communication routes : the roads from Béziers to Pézenas and from Saint-Thibéry to Alignan-du-Vent. From historical records, it is known that in 1199, the powerful Viscount of Béziers, Raymond Roger Trencavel, authorised his vassal Etienne de Servian to build a forcia on the podium of Valros. But, from 1210, during the Albigensian Crusade, Etienne de Servian was forced to recount, under pressure from the troops of Simon de Montfort. Thus, the fortress had only a short functioning military life. It was dismantled soon after its construction, in the first half of the 13th century. Thereafter, the site continued to be frequented by troops who took water from the cistern, which never dried up.[1]

Architecture

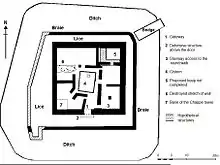

The fort was protected externally by a dry moat and a first enceinte, the braie, defining a peripheral circuit, the lice. This lice was, in case of need, defended by a clever device of horizontal removable posts. In the north east corner of the braie, a broken stretch of wall suggests the location of the access bridge. The modern footbridge now stands there. The shortest distance from the bridge to the entrance to the fort obliged an assailant to go left along the wall, exposing his right side, the most vulnerable because not protected by armour.[1]

The fort itself, a 24 m square, has a wall 1.80 m thick with a single opening, in the south. Above this gate was a hourd, a kind of wooden hut, designed to allow firing down onto assailants. The holes for the supporting structure are still visible.[1]

The interior was occupied by lean-to buildings whose roofs fed a central cistern of approximately 40m3 capacity. The surrounding wall, which reached a height of at least 11 m, supported a round walk and, certainly, crenellation. To the left of the door, traces of projecting stones suggest the presence of a staircase giving access to the round walk. In the north east corner, opposite the bridge, stored stones are witness to a project to build a keep, never completed. Three materials were used in the construction. Basalt was used for the centre of the surrounding walls, all of the upper parts and for the external enceinte. The basalt came from the digging of the moat. Volcanic breccia, a conglomerate, was used for the parts of walls above a height of 7 m. This rock was taken from a quarry on the east flank of the hill. Limestone from Pézenas was used in the construction of the cistern and the entrance door.[1]

Telegraph tower

The small square tower nestled in the south west corner of the fortress (number 7 on the plan above) is a remnant of the aerial telegraphy invented at the end of the 18th century by the engineer Claude Chappe (1763-1805), using semaphore signals.[1]

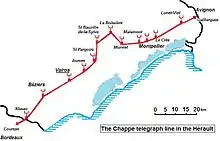

The first semaphore telegraphy line was established in 1794 between Paris and Lille.[2] The French network extended over 5,000 km with 534 stations serving 29 towns. Installed in 1834, the line linking Avignon to Narbonne, via Valros, was functioning until 1853. The semaphore network was then replaced by electric telegraphy. The tours de Chappe (Chappe towers), every 12 km or so, were built on high points. Each station was equipped with a mechanism for transmission and two telescopes to receive a message and to control its onward transmission.[3] The mechanism consisted of a vertical mast supporting a 4.60 m long movable arm, the regulateur. At either end of the latter was a secondary arm, 2 m long, the indicateurs. The mast extended down into the interior of the tower into a tight room, 3 m by 3 m, sheltering the stationnaire, the solitary worker glued to his telescopes. For speed, and confidentiality, messages were encoded using a table where each figure signified a word or phrase. To transmit a message, the regulateur was placed either horizontally or vertically. The indicateurs were articulated every 45o, with 7 positions for each. This gave a total of 98 combinations (7 X 7 X 2), of which six were reserved for the service - the only ones whose meanings were known to the stationnaire. The total repertoire of messages was, therefore, 92 pages of 92 lines, a total of 8,464. Signals were sent in groups of two: the first number for the number of the page, the second for the number of the line on that page.[1]

See also

References

- Information provided on notice boards on site

- Tour du télégraphe Chappe Archived 2011-09-28 at the Wayback Machine (in French)

- Beyer, Rick, The Greatest Stories Never Told, p.60, A&E Television Networks / The History Channel, ISBN 0-06-001401-6