Digitalis

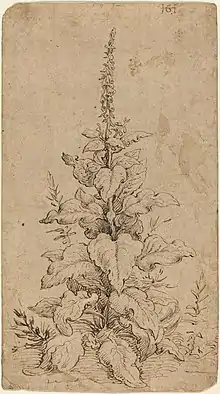

Digitalis (/ˌdɪdʒɪˈteɪlɪs/[2] or /ˌdɪdʒɪˈtælɪs/[3]) is a genus of about 20 species of herbaceous perennial plants, shrubs, and biennials, commonly called foxgloves.

| Foxglove | |

|---|---|

| |

| Digitalis purpurea (Common foxglove) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Lamiales |

| Family: | Plantaginaceae |

| Tribe: | Digitalideae |

| Genus: | Digitalis Tourn. ex L.[1] |

| Species | |

|

Over 20 species, see text: | |

Digitalis is native to Europe, Western Asia, and northwestern Africa. The flowers are tubular in shape, produced on a tall spike, and vary in colour with species, from purple to pink, white, and yellow. The scientific name means "finger". The genus was traditionally placed in the figwort family, Scrophulariaceae, but phylogenetic research led taxonomists to move it to the Veronicaceae in 2001.[4] More recent phylogenetic work has placed it in the much enlarged family Plantaginaceae.

The best-known species is the common foxglove, Digitalis purpurea. This biennial is often grown as an ornamental plant due to its vivid flowers, which range in colour from various purple tints through pink and purely white. The flowers can also possess various marks and spottings. Other garden-worthy species include D. ferruginea, D. grandiflora, D. lutea, and D. parviflora.[5]

The term digitalis is also used for drug preparations that contain cardiac glycosides, particularly one called digoxin, extracted from various plants of this genus. Foxglove has medicinal uses but is also very toxic to humans and other animals, and consumption can even lead to death.

Etymology

The generic epithet Digitalis is from the Latin digitus (finger).[6] Leonhart Fuchs first invented the name for this plant in his 1542 book De historia stirpium commentarii insignes (Notable comments on the history of plants), based upon the German vernacular name Fingerhut,[7][8] which translates literally as 'finger hat', but actually means 'thimble'.

The name is recorded in Old English as 'foxes glofe/glofa' or 'fox's glove'.[9] Over time, folk myths obscured the literal origins of the name, insinuating that foxes wore the flowers on their paws to silence their movements as they stealthily hunted their prey. The woody hillsides where the foxes made their dens were often covered with the toxic flowers. Some of the more menacing names, such as "witch's glove", reference the toxicity of the plant.[8]

Henry Fox Talbot (1847) proposed 'folks' glove', where 'folk' means fairy. Similarly, R. C. A. Prior (1863) suggested an etymology of 'foxes-glew', meaning 'fairy music'. However, neither of these suggestions account for the Old English form foxes glofa.[9]

Taxonomy

Species

The Flora Europaea originally recognised a number of species now seen as synonyms of Digitalis purpurea, or others: D. dubia, D. leucophaea, D. micrantha and D. trojana.[10] As of 2017, Plants of the World Online recognises the following 27 species (and a number of hybrids):[1]

- Digitalis atlantica Pomel

- Digitalis canariensis L.

- Digitalis cariensis Boiss. ex Jaub. & Spach

- Digitalis cedretorum (Emb.) Maire

- Digitalis chalcantha (Svent. & O'Shan.) Albach, Bräuchler & Heubl

- Digitalis ciliata Trautv.

- Digitalis davisiana Heywood

- Digitalis ferruginea L.

- Digitalis fuscescens Waldst. & Kit.

- Digitalis grandiflora Mill.

- Digitalis ikarica (P.H.Davis) Strid

- Digitalis isabelliana (Webb) Linding.

- Digitalis laevigata Waldst. & Kit.

- Digitalis lamarckii Ivanina

- Digitalis lanata Ehrh.

- Digitalis lutea L.

- Digitalis mariana Boiss.

- Digitalis minor L.

- Digitalis nervosa Steud. & Hochst. ex Benth.

- Digitalis obscura L.

- Digitalis parviflora Jacq.

- Digitalis purpurea L.

- Digitalis sceptrum L.f.

- Digitalis subalpina Braun-Blanq.

- Digitalis thapsi L.

- Digitalis transiens Maire

- Digitalis viridiflora Lindl.

Hybrids

- Digitalis × coutinhoi Samp.

- Digitalis × fulva Lindl.

- Digitalis × macedonica Heywood

- Digitalis × media Roth

- Digitalis × pelia Zerbst & Bocquet

- Digitalis × purpurascens Roth

- Digitalis × sibirica (Lindley) Werner had been considered a valid species since it was first described by the English botanist and gardener John Lindley in 1821,[11] but it was considered a hybrid of D. grandiflora and D. laevigata by the German botanist Klaus Werner in 1960.[12]

Systematics

The first full monograph regarding this genus was written by Lindley in 1821. He included two sections, a section Isoplexis including two species, and the main section Digitalis with three subsections, including 2Y species, a number of which are now seen as synonyms or hybrids.[11]

In the last full monograph of the genus in 1965, Werner classified the 19 recognised species in five sections (four species from Macaronesia were separated in the genus Isoplexis at the time):[13][14][15]

- In the section Digitalis, along with the type species D. purpurea, four other species (as recognised as the time) were placed: D. thapsi, D. dubia, D. heywoodii and D. mariana.

- The monotypic section Frutescentes contained only D. obscura.

- The section Grandiflorae, which was also called section Macranthae by Vernon Hilton Heywood. It included, along with the type species D. grandiflora, also D. atlantica, D. ciliata and D. davisiana.

- Globiflorae included five species: D. laevigata, D. nervosa, D. ferruginea, D. cariensis and D. lanata.

- Tubiflorae included four species: D. subalpina, D. lutea, D. viridiflora and D. parviflora.

In their 2000 book about Digitalis, Luckner and Wichtl continued to uphold Werner's classification of the 19 species,[15][14][16] but molecular studies into the phylogeny of the genus published in 2004 found that although four of Werner's sections were supported by the genetics, the section Tubiflorae was polyphyletic, and that the species D. lutea and D. viridiflora should be placed in the section Grandiflorae.[17] This study, as well as a number of other studies published around that time, reunited the genus Isoplexis with Digitalis, increasing the number of species to 23.[14][17]

Peter Hadland Davis, an expert on the flora of Turkey, had used a different circumscription than Werner in his works, and recognised eight species in the country. A 2016 molecular phylogenetic study into the relationships of the Turkish species in the section Globiflorae aimed to reconcile this discrepancy, finding that the classification as proposed by Davis was largely correct: Globiflorae contained as distinct species D. cariensis, D. ferruginea, D. lamarckii, D. lanata and D. nervosa, and D. trojana was subsumed at the infraspecific rank as D. lanata subsp. trojana. This study listed 23 species: D. transiens, D. cedretorum, D. ikarica and D. fuscescens were not mentioned. D. parviflora and D. subalpina were not tested in this study,[12] but the 2004 study found these two species situated within the section Globiflorae.[17]

Ecology

Larvae of the foxglove pug, a moth, consume the flowers of the common foxglove for food. Other species of Lepidoptera eat the leaves, including the lesser yellow underwing.[18]

Uses

Historical uses

Nicholas Culpeper included Foxglove in his 1652 herbal medicine guide, The English Physician. He cited its use for healing wounds (both fresh and old), as a purgative, for "the King's Evil" ( mycobacterial cervical lymphadenitis), for "the falling sickness" (epilepsy), and for "a scabby head".[19] There is no empirical evidence for these claims, and it is not used for these conditions in modern medicine, only for slowing excessive heart rate in certain circumstances and/or strengthening heart muscle contraction in heart failure.[20]

Medicinal uses

Digitalis is an example of a drug derived from a plant that was formerly used by herbalists; herbalists have largely abandoned its use because of its narrow therapeutic index and the difficulty of determining the amount of active drug in herbal preparations. Once the usefulness of digitalis in regulating the human pulse was understood, it was employed for a variety of purposes, including the treatment of epilepsy and other seizure disorders, which are now considered to be inappropriate treatments.

A group of medicines extracted from foxglove plants are called digitalin. The use of D. purpurea extract containing cardiac glycosides for the treatment of heart conditions was first described in the English-speaking medical literature by William Withering, in 1785,[21][22][23] which is considered the beginning of modern therapeutics. In contemporary medicine, digitalis (usually digoxin) is obtained from D. lanata.[24][25] It is used to increase cardiac contractility (it is a positive inotrope) and as an antiarrhythmic agent to control the heart rate, particularly in the irregular (and often fast) atrial fibrillation. Digitalis is hence often prescribed for patients in atrial fibrillation, especially if they have been diagnosed with congestive heart failure. Digoxin was approved for heart failure in 1998 under current regulations by the Food and Drug Administration on the basis of prospective, randomized study and clinical trials. It was also approved for the control of ventricular response rate for patients with atrial fibrillation. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines recommend digoxin for symptomatic chronic heart failure for patients with reduced systolic function, preservation of systolic function, and/or rate control for atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular response. Heart Failure Society of America guidelines for heart failure provide similar recommendations. Despite its relatively recent approval by the Food and Drug Administration and the guideline recommendations, the therapeutic use of digoxin is declining in patients with heart failure—likely the result of several factors. The main factor is the more recent introduction of several drugs shown in randomised controlled studies to improve outcomes in heart failure.[26] Safety concerns regarding a proposed link between digoxin therapy and increased mortality seen in observational studies may have contributed to the decline in therapeutic use of digoxin, however a systematic review of 75 studies including four million patient years of patient follow-up showed that in properly designed randomised controlled studies, mortality was no higher in patients given digoxin than in those given placebo.[27]

Variations

A group of pharmacologically active compounds are extracted mostly from the leaves of the second year's growth, and in pure form are referred to by common chemical names, such as digitoxin or digoxin, or by brand names such as Crystodigin and Lanoxin, respectively. The two drugs differ in that digoxin has an additional hydroxyl group at the C-3 position on the B-ring (adjacent to the pentane). This results in digoxin having a half-life of about one day (and increasing with impaired kidney function), whereas digitoxin's is about 7 days and not affected by kidney function. Both molecules include a lactone and a triple-repeating sugar called a glycoside.

Mechanism of action

Digitalis works by inhibiting sodium-potassium ATPase. This results in an increased intracellular concentration of sodium ions and thus a decreased concentration gradient across the cell membrane. This increase in intracellular sodium causes the Na/Ca exchanger to reverse potential, i.e., transition from pumping sodium into the cell in exchange for pumping calcium out of the cell, to pumping sodium out of the cell in exchange for pumping calcium into the cell. This leads to an increase in cytoplasmic calcium concentration, which improves cardiac contractility.[28] Under normal physiological conditions, the cytoplasmic calcium used in cardiac contractions originates from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, an intracellular organelle that stores calcium. Human newborns, some animals, and patients with chronic heart failure lack well developed and fully functioning sarcoplasmic reticula and must rely on the Na/Ca exchanger to provide all or a majority of the cytoplasmic calcium required for cardiac contraction. For this to occur, cytoplasmic sodium must exceed its typical concentration to favour a reversal in potential, which naturally occurs in human newborns and some animals primarily through an elevated heart rate; in patients with chronic heart failure it occurs through the administration of digitalis. As a result of increased contractility, stroke volume is increased. Ultimately, digitalis increases cardiac output (cardiac output = stroke volume x heart rate). This is the mechanism that makes this drug a popular treatment for congestive heart failure, which is characterized by low cardiac output.

Digitalis also has a vagal effect on the parasympathetic nervous system, and can be used to slow the ventricular rate during atrial fibrillation (unless there's an accessory pathway, when it can paradoxically increase the heart rate).[29] The dependence on the vagal effect means digitalis is not effective when a patient has a high sympathetic nervous system drive, which is the case with acutely ill persons, and also during exercise.[30][31]

Molecular probes

Digoxigenin (DIG) is a steroid found in the flowers and leaves of Digitalis species, and is extracted from D. lanata. Digoxigenin can be used as a molecular probe to detect mRNA in situ and label DNA, RNA, and oligonucleotides.[32] It can easily be attached to nucleotides such as uridine by chemical modifications. DIG molecules are often linked to nucleotides; DIG-labelled uridine can then be incorporated into RNA via in vitro transcription. Once hybridisation occurs, RNA with the incorporated DIG-U can be detected with anti-DIG antibodies conjugated to alkaline phosphatase. To reveal the hybridised transcripts, a chromogen can be used which reacts with the alkaline phosphatase to produce a coloured precipitate.

Toxicity

Depending on the species, the digitalis plant may contain several deadly physiological and chemically related cardiac and steroidal glycosides. Thus, the digitalis plants have earned several, more sinister, names: dead man's bells and witch's gloves. The toxins can be absorbed via the skin[33] or ingestion.

Digitalis intoxication, known as digitalism, results from an overdose of digitalis and can cause gastrointestinal, cardiac and neurological effects. The former include appetite loss, nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea; the cardiac symptoms include both tachycardia, and bradycardia (either of which, if severe enough, can result in syncope—see below); and the neurological effects include fatigue, delirium, and rarely xanthopsia (jaundiced or yellow vision).[34][35][36] Other oculotoxic effects of digitalis include generalized blurry vision, as well as the appearance of blurred outlines ('halos').[37] Other things mentioned are dilated pupils, drooling, weakness, collapse, seizures, and even death.

Digitalis poisoning can cause indirect inhibition of the atrioventricular node via a direct effect on the vagal nucleus. This results in bradycardia (decreased heart rate) or if severe enough, heart block. The direct effect of cardiac glycosides on heart muscle cells is to increase contraction of the cells, both in force and frequency, tending to produce tachycardia (increased heart rate), depending on the dose, the condition of one's heart, and the prevailing chemistry of the blood (specifically any of: low potassium, high calcium and low magnesium).[38] Electrical cardioversion (to "shock" the heart) is generally not indicated in ventricular fibrillation in digitalis toxicity, as it can make the rhythm disturbance more complicated or sustained.[39][40] Furthermore, the classic drug of choice for ventricular fibrillation in emergency setting,[41] amiodarone, can worsen the dysrhythmia caused by digitalis, therefore, the second-choice drug lidocaine is more commonly used.[42] Mild toxicity is treated by stopping the medication and general supportive measures; severe toxicity is treated with anti-digoxin antibody fragments.

The entire plant is toxic (including the roots and seeds). Mortality is rare, but case reports do exist. Most plant exposures occur in children younger than six years and are usually unintentional and without associated significant toxicity. More serious toxicity occurs with intentional ingestion by adolescents and adults.[43]

In some instances, people have confused foxglove with the relatively harmless comfrey (Symphytum) plant, which is sometimes brewed into a tea, with fatal consequences. Other fatal accidents involve children drinking the water in a vase containing digitalis plants.[44] Drying does not reduce the toxicity of the plant. The plant is toxic to animals, including all classes of livestock and poultry, as well as felines and canines.

In popular culture

According to 1981 speculation, Vincent van Gogh's "Yellow Period" may have been influenced by digitalis, because it had been proposed as a therapy to control epilepsy around this time, and there are two paintings by the artist where the plant is present.[45] Other studies immediately questioned this: there are a large number of other possible explanations for van Gogh's choice of palette,[46][47] there is no evidence that van Gogh was ever given the drug or that his physician prescribed it, he was tested and had no xanthopsia, and in his many letters of the time he makes it clear that he simply liked using the colour yellow,[47][48][49] but it has remained a popular concept.[50]

References

- "Digitalis Tourn. ex L." Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. 2017. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- Oxford English Dictionary: "Digitalis"

- "Digitalis". Dictionary.com.

- Olmstead, R. G.; de Pamphilis, C. W.; Wolfe, A. D.; Young, N. D.; Elisons, W. J.; Reeves, P. A. (2001). "Disintegration of the Scrophulariaceae". American Journal of Botany. 88 (2): 348–361. doi:10.2307/2657024. JSTOR 2657024. PMID 11222255. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- Brickell, Christopher, ed. (2008). The Royal Horticultural Society A-Z Encyclopedia of Garden Plants. Dorling Kindersley. p. 377. ISBN 9781405332965.

- Hollman, A (September 1985). "Plants and cardiac glycosides". British Heart Journal. 54 (3): 258–261. doi:10.1136/hrt.54.3.258. PMC 481893. PMID 4041297.

- Fuchs, Leonhart (1542). De historia stirpium commentarii insignes (in Latin). Basel: In officina Isingriniana. pp. 892–893.

Apellauimus autem Digitalem, alludentes ad germanicam nomenclaturam...

- Klingaman, Gerald (17 May 2002). "Plant of the Week: Foxglove". University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- Liberman, Anatoly (10 November 2010). "Etymologists at War with a Flower: Foxglove". OUPblog. Archived from the original on 8 May 2013. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

In sum, foxglove means foxglove, and this disturbing fact has to be accepted.

- "Flora Europaea: Digitalis species list".

- Lindley, John (1821). Digitalium monographia: sistens historiam botanicam generis, tabulis omnium specierum hactenus cognitarum illustratam ut plurimum confectis ad icones (in Latin). London: Arthur Taylor for J.H. Bohte. pp. 1–27. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.160067.

- Eker, İsmail; Yücesan, Buhara; Sameeullah, Muhammad; Welß, Walter; Müller-Uri, Frieder; Gürel, Ekrem; Kreis, Wolfgang (January 2016). "Phylogeny of Anatolian (Turkey) species in the Digitalis sect. Globiflorae (Plantaginaceae)" (PDF). Phytotaxa. 244 (3): 263. doi:10.11646/phytotaxa.244.3.3. ISSN 1179-3163. S2CID 87777389. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 December 2021. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- Werner, Klaus (1965). "Taxonomie und Phylogenie der Gattungen Isoplexis (Lindl.) Benth. und Digitalis L.". Feddes Repertorium (in German). 70 (1–3): 109–135. doi:10.1002/fedr.19650700106.

- Kreis, Wolfgang (2017). "The Foxgloves (Digitalis) Revisited". Planta Medica. 83 (12–13): 962–976. doi:10.1055/s-0043-111240. PMID 28561136.

- Wichtl, Max (2001). "Digitalis L. -Fingerhut (Scrophulariaceae) - eine wichtige Arzneipflanzengattung". Stapfia (in German). 75 (164): 89–100. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- Luckner, M.; Wichtl, Max (2000). Digitalis: Geschichte, Biologie, Chemie, Physiologie, Molekularbiologie, medizinische Anwendung. Handbuch für Ärzte, Apotheker und andere Naturwissenschaftler (in German). Stuttgart: Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft. ISBN 3-8047-1705-5.

- Bräuchler, C.; Meimberg, H.; Heubl, G. (2004). "Molecular phylogeny of the genera Digitalis L. and Isoplexis (Lindley) Loudon (Veronicaceae) based on ITS- and trnL-F sequences". Plant Systematics and Evolution. 248 (1–4): 111–128. doi:10.1007/s00606-004-0145-z. S2CID 25480255.

- Robinson, G. S.; Ackery, P. R.; Kitching, I. J.; Beccaloni, G. W.; Hernández, L. M. (2010). "Digitalis". HOSTS – A Database of the World's Lepidopteran Hostplants. Natural History Museum, London. doi:10.5519/havt50xw. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- Culpeper, Nicholas (1652). The English Physician, Etc (1st ed.). London: William Bentley. pp. 97–98. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- "BNF (only available in the UK)". NICE. BMJ & Pharmaceutical Press. Retrieved 20 February 2023.

- Withering, William (1785). An Account of the Foxglove and some of its Medical Uses. Birmingham, England: M. Swinney.

- Goldthorp, W. O. (2009). "Medical Classics: An Account of the Foxglove and Some of its Medicinal Uses by William Withering, published 1785". British Medical Journal. 338: b2189. doi:10.1136/bmj.b2189. S2CID 72429441.

- Simpson, Beryl Brintnall; Ogorzaly, Molly Coner (2001). Economic Botany (3rd ed.). Boston: Mc Graw Hill. p. 529. ISBN 9780072909388.

- Hollman, A. (April 1996). "Drugs for atrial fibrillation. Digoxin comes from Digitalis lanata". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 312 (7035): 912. doi:10.1136/bmj.312.7035.912. PMC 2350584. PMID 8611904.

- Weisse, Allen B. (January 2010). "A Fond Farewell to the Foxglove? The Decline in the Use of Digitalis". Journal of Cardiac Failure. 16 (1): 45–48. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2009.08.001. PMID 20123317.

- Anon. "Medications Used to Treat Heart Failure". www.heart.org. American Heart Association. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- Ziff, Oliver J.; Lane, Deirdre A.; Samra, Monica; Griffith, Michael; Kirchhof, Paulus; Lip, Gregory Y. H.; Steeds, Richard P.; Townend, Jonathan; Kotecha, Dipak (30 August 2015). "Safety and efficacy of digoxin: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational and controlled trial data". British Medical Journal. 351: h4451. doi:10.1136/bmj.h4451. PMC 4553205. PMID 26321114. S2CID 9995597.

- Akera, Tai; Brody, Theodore M. (1985). "Sodium ion and the cardiac actions of digitalis". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 6: 296–298. doi:10.1016/0165-6147(85)90136-1.

- Fuster, Valentin; Rydén, Lars E.; Asinger, Richard W.; Cannom, David S.; Crijns, Harry J.; Frye, Robert L.; Halperin, Jonathan L.; Kay, G. Neal; Klein, Werner W.; Lévy, Samuel; McNamara, Robert L.; Prystowsky, Eric N.; Wann, L. Samuel; Wyse, D. George; Gibbons, Raymond J.; Antman, Elliott M.; Alpert, Joseph S.; Faxon, David P.; Fuster, Valentin; Gregoratos, Gabriel; Hiratzka, Loren F.; Jacobs, Alice K.; Russell, Richard O.; Smith, Sidney C.; Klein, Werner W.; Alonso-Garcia, Angeles; Blomström-Lundqvist, Carina; de Backer, Guy; Flather, Marcus; Hradec, Jaromir; Oto, Ali; Parkhomenko, Alexander; Silber, Sigmund; Torbicki, Adam (23 October 2001). "ACC/AHA/ESC Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: Executive Summary A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines and Policy Conferences (Committee to Develop Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation) Developed in Collaboration With the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology". Circulation. 104 (17): 2118–2150. doi:10.1161/circ.104.17.2118. ISSN 0009-7322. PMID 11673357.

- Watanabe, August M. (1 May 1985). "Digitalis and the autonomic nervous system". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 5 (5): 35A–42A. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(85)80461-7. ISSN 0735-1097. PMID 3886751.

- Tonkon, M. J.; Lee, G.; DeMaria, A. N.; Miller, R. R.; Mason, D. T. (December 1977). "Effects of digitalis on the exercise electrocardiogram in normal adult subjects". Chest. 72 (6): 714–718. doi:10.1378/chest.72.6.714. ISSN 0012-3692. PMID 923306.

- Glick, Bernard R. (4 May 2018). Methods in Plant Molecular Biology and Biotechnology. CRC Press. p. 183. ISBN 978-1-351-09139-8.

- "GRECIAN FOXGLOVE". Minnesota Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- Lewis, Robert Alan (1998). Lewis Dictionary of Toxicology. p. 387. ISBN 978-1-56670-223-2.

Symptoms may include gastrointestinal disturbances and pain, severe headache, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, irregular pulse, and yellow vision...

- "Digoxin Toxicity". RCEMLearning. Retrieved 20 February 2023.

- Renard, D; Rubli, E; Voide, N; Borruat, FX; Rothuizen, LE (23 August 2015). "Spectrum of digoxin-induced ocular toxicity: a case report and literature review". BMC Research Notes. 8: 368. doi:10.1186/s13104-015-1367-6. PMC 4546820. PMID 26298392.

- Goldfrank, L. W. (2006). Goldfrank's Toxicologic Emergencies (8th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Rehman, Rameez; Dawson, Andrew H.; Hai, Ofek (2022). "Digitalis Toxicity". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 29083729. Retrieved 20 February 2023.

- Abou-Donia, Mohamed (2015). Mammalian Toxicology. John Wiley & Sons. p. 631. ISBN 9781118683316.

- Fuster, Valentin; Rydén, Lars E.; Cannom, David S.; Crijns, Harry J.; Curtis, Anne B.; Ellenbogen, Kenneth A.; Halperin, Jonathan L.; Le Heuzey, Jean-Yves; Kay, G. Neal; Lowe, James E.; Olsson, S. Bertil; Prystowsky, Eric N.; Tamargo, Juan Luis; Wann, Samuel (August 2006). "ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation—Executive Summary". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 48 (4): 861. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2006.07.009. PMID 16904574. S2CID 8975477.

- "European Resuscitation Council".

- Lee Lopez, Orchid (2011). Back to Basics: Critical Care Transport Certification Review. Xlibris Corporation. p. 290. ISBN 9781456862749.

- "Cardiac Glycoside Plant Poisoning: Medscape reference". Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- Anon. "Notes on poisoning:Digitalis purpura". Canadian poisonous plants information system. Canadian Biodiversity Information Facility. Archived from the original on 13 October 2011. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- Lee, T. C. (20 February 1981). "Van Gogh's vision. Digitalis intoxication?". JAMA. 245 (7): 727–729. doi:10.1001/jama.1981.03310320049025. PMID 7007674.

- Lanthony, P. (October 1989). "[Van Gogh's xanthopsia]". Bulletin des Sociétés d'Ophtalmologie Française (in French). 89 (10): 1133–1134. PMID 2695267.

- Arnold, Wilfred Niels; Loftus, Loretta S. (1 September 1991). "Xanthopsia and van Gogh's yellow palette" (PDF). Eye. 5 (5): 503–510. doi:10.1038/eye.1991.93. PMID 1794418. S2CID 26723081. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 October 2018. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- Gruener, Anna (July 2013). "Vincent van Gogh's yellow vision". British Journal of General Practice. 63 (612): 370–371. doi:10.3399/bjgp13X669266. PMC 3693787. PMID 23834871. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- Voskuil, Piet (October 2020). "Vincent van Gogh and his illness. A reflection on a posthumous diagnostic exercise". Epilepsy & Behavior. 111 (107258): 107258. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.107258. PMID 32629415. S2CID 220323719.

- Harkup, Kathryn (10 August 2017). "It was all yellow: did digitalis affect the way Van Gogh saw the world?". The Guardian (UK). Retrieved 28 November 2020.