François Pierre Joseph Amey

François Pierre Joseph Amey (2 October 1768 – 16 November 1850) became a French division commander during the Napoleonic Wars. He enlisted in the French Royal Army in 1783 and joined a volunteer battalion in 1792. He won promotion to general of brigade in 1793 during the War in the Vendée. He held a command during the period of the infernal columns and his career became obscure until 1799 when he supported Napoleon's coup. He went on the Saint-Domingue expedition in 1802–1803 and later filled posts in the interior. In 1806–1807 he led a brigade at Jena, Golymin and Eylau where he was wounded.

François Pierre Joseph Amey | |

|---|---|

| Born | 2 October 1768 Sélestat, Bas-Rhin, France |

| Died | 16 November 1850 (aged 82) Strasbourg, France |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | Infantry |

| Years of service | |

| Rank | General of Division |

| Battles/wars |

|

| Awards | Légion d'Honneur, GC 1813 Order of Saint Louis, 1814 |

| Other work | Baron of the Empire, 1810 Mayor of Sélestat, 1820–30 |

Sent to Spain in 1808 in command of German troops, Amey fought at the Third Siege of Gerona the following year. In 1812 he participated in the French invasion of Russia and led his troops at the First and Second Battles of Polotsk. He was promoted to general of division and fought at the Berezina. He fought at Arnhem in fall 1813. While leading a division of recruits, he was wounded and captured after a heroic defense in the Battle of Fère-Champenoise in 1814. After rallying to Napoleon during the Hundred Days he was retired in 1815. He served as mayor of Sélestat for ten years then returned to military service in 1830–1833. His surname is one of the names inscribed under the Arc de Triomphe, on Column 1.

Revolution

Amey was born in Sélestat on 2 October 1768 to parents François Pierre Amey and Marie-Ursule Collignon. His Swiss-born father was the surgeon-major of the Waldner Swiss Regiment while his mother was a local girl.[1] On 1 October 1783 he joined the Vigier Swiss Regiment as a cadet. He became a sous lieutenant on 18 June 1788. He was involved in the Châteauvieux Regiment's mutiny at Nancy on 31 August 1790. He was dismissed from military service on 7 October 1792. Three days later he became the captain of the 1st Company of the Rhine Légion.[2] A month later he was an aide de camp to Adam Philippe, Comte de Custine but in 1793 he was sent to fight in the War in the Vendée.[3] Amey became adjutant general chef de bataillon on 23 June 1793 and chef de brigade on 23 October the same year. During this time he fought with the Army of the Coasts of La Rochelle and Army of the West under such generals as François Séverin Marceau-Desgraviers, Jean-Baptiste Kléber, Charles François Duhoux and Jacques-François Menou.[2] On 28 November 1793 he won promotion to general of brigade.[4] He distinguished himself at the Battle of Le Mans on 12–13 December where he had a horse killed under him.[3]

Louis Marie Turreau took over the direction of the conflict on 30 December. Turreau started a campaign of savage repression against the Vendeans by "infernal columns" on 24 January 1794. The columns roamed the countryside burning farms and killing any rebels they caught, including in many cases, women and children. Instead of ending the revolt, the severity of the repression provoked a fresh uprising. The heavy hand of the undisciplined Republican armies sometimes fell on those citizens who were loyal and, for this, the government suspended Turreau on 13 May.[5] During the operation Amey commanded a garrison at Les Herbiers.[6] According to one account his troops were guilty of some of the worst excesses.[7] He was suspended for a month beginning in August 1794.[3] Few generals who served in the Vendée during the first half of 1794 had successful careers; Amey and Georges Joseph Dufour became the exceptions.[7]

After his suspension, Amey served in the Army of the Alps and, according to one account, was put on the inactive list in July 1795.[3] Another source stated that he was employed with the Army of the Alps and the Army of the Rhine until 1799. He was at Saint-Cloud and became a participant in Napoleon's successful Coup of 18 Brumaire on 9 November 1799. Immediately afterward he was assigned to the 17th Military Division and became the president of the council of revision.[2] Amey transferred to the Army of the Rhine in 1800.[3] He went on the Saint-Domingue expedition in 1802 and returned the following year to an appointment as a Chevalier of the Légion d'Honneur on 11 December 1803. He became a Commander of the Légion d'Honneur on 14 June 1804.[2]

Empire

Amey was put in command of the Ardennes department in the 2nd Military Division until 1806. At the beginning of the War of the Fourth Coalition in September 1806,[3] he was put in command of an infantry brigade in Étienne Heudelet de Bierre's 2nd Division in Marshal Pierre Augereau's VII Corps. The brigade consisted of three battalions of the 7th Light Infantry Regiment.[8] The 7th Light was engaged at the Battle of Jena on 14 October 1806.[9] He fought at the Battle of Golymin on 26 December 1806 and the Battle of Eylau on 7–8 February 1807 where he was wounded.[3] At Eylau, the VII Corps suffered such heavy losses that it was dissolved and its survivors distributed to other corps.[10] Amey became governor of Elbing and later took command of a brigade in Claude Carra Saint-Cyr's division of Marshal Jean-de-Dieu Soult's IV Corps.[3]

On 19 March 1808, Napoleon named Amey a Baron of the Empire with an endowment of 4,000 French francs.[2] His first wife Anne Marguerite Élisabeth Hantzler died that same day.[1] In January 1809 he took command of the German Legion in the VII Corps' 1st Division in Catalonia and fought at the Third Siege of Gerona.[3] In Jean-Antoine Verdier's 4th Division, he led the German brigade which consisted of the Würzburg and the 1st and 2nd Berg Regiments.[11] The Spanish defenders resisted heroically and losses were horrific. During the siege the Würzburgers lost 870 casualties out of 1,519, the 1st Berg lost 605 out of 1,310 and the 2nd Berg lost 709 out of 1,313 men.[12] After months of siege the French-Allied besiegers captured the key City Redoubt and on 7 December 1809, the Spanish garrison mounted an all-out attack to recapture the work. This completely failed and resulted in the additional loss of the Calvary and Chapter redoubts. The disaster led to the garrison's final surrender on 11 December.[13] From his position near Montjuich, Amey launched the counterattack which took the Spanish in flank and overran the two redoubts.[2]

He transferred to Holland in 1810 and remained there until 1812.[3] On 21 November 1810 he married his second wife, Caroline Henriette Charlotte de Polentz, the daughter of a Prussian baron.[1] In the French invasion of Russia he led the 2nd Brigade in Pierre Hugues Victoire Merle's 9th Division of the II Corps under Marshal Nicolas Oudinot. The brigade included 1,513 men of the 4th Swiss Line Infantry Regiment and 1,582 men of the 3rd Croatian Regiment, each with two 3-pound cannons attached.[14] He was recognized in the official bulletin for the distinguished part he played at the First Battle of Polotsk on 18–19 August 1812.[2] He also led his brigade at the Second Battle of Polotsk.[3] He was promoted general of division on 19 November 1812[2] and was wounded at the Battle of Berezina two weeks later. In 1813 he was appointed to command the camp of Utrecht in Holland and was awarded the Grand Cross of the Légion d'Honneur.[3]

With a Prussian corps under Friedrich Wilhelm Freiherr von Bülow about to invade the Netherlands in mid-November 1813, Marshal Jacques MacDonald directed that the line of the Ijssel River be held. Accordingly, Amey was given a 2,000-man flying column consisting of two battalions of infantry, one battalion of customs agents and a squadron of mounted gendarmes. On 14 November Amey left Wesel and marched toward Arnhem and Deventer.[15] On 23 November his column recovered Doesburg from a force of Don Cossacks. On 25 November, his column bumped into a Prussian force and was driven back to Arnhem after a running skirmish. The Prussians attempted to rush Arnhem's entrenched camp but were repulsed.[16] On 28 November, MacDonald reinforced Arnhem to a strength of 4,000 and put Henri François Marie Charpentier in command. The next day, Charpentier pushed back the Prussian outposts, but MacDonald realized the danger and ordered him to retreat. Charpentier disregarded his instructions and was defeated on 30 November in the Battle of Arnhem. During the action Charpentier was wounded so Amey took command of the withdrawing French forces.[17]

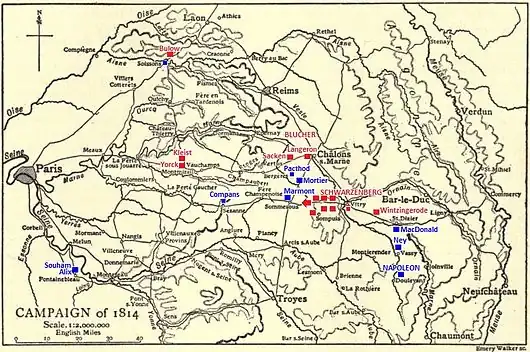

While Napoleon defeated Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher's Army of Silesia in the Six Days Campaign, Karl Philipp, Prince of Schwarzenberg's Army of Bohemia forced its way across the Seine River. With the French forces falling back to the Yerres River, Napoleon sent MacDonald's XI Corps south to Guignes which it reached late on 14 February 1814.[18] This was followed by a French victory in the Battle of Montereau on 18 February.[19] At this time the 8,000-man XI Corps included the divisions of Michel Sylvestre Brayer, Joseph Jean Baptiste Albert and Amey.[20] On 17–18 February Amey's division only included the 2nd Brigade which was made up of two battalions each of the 149th Line and Calvados National Guard and one battalion of the Manche National Guard.[21] On 28 February, Napoleon ordered Amey's division withdrawn to Troyes to guard the army's wagon train and artillery parks.[22] On 1 March the division counted only 772 infantry and a 70-man horse artillery company with four 8-pounders and one howitzer.[23]

Schwarzenberg's 100,000-strong army defeated Napoleon's 30,000 troops at the Battle of Arcis-sur-Aube on 20–21 March 1814.[24] Napoleon attacked the Allies before MacDonald's troops all joined him and sent orders to that marshal to hurry up.[25] When the Allies forced the French to retreat on the evening of the 21st, MacDonald's two lead divisions just arrived and Amey's division was well to the west at Anglure.[26] MacDonald's troops formed the rearguard of Napoleon's army as it retreated to the northeast toward Vitry-le-François. On the 23 March, an ambiguously-written order sent Amey's troops to Sézanne, leaving the unguarded artillery park to be attacked by the Russian Guard light cavalry. Another French unit rescued part of the convoy but 15 artillery pieces and 300 prisoners were carried off.[27] At this time, Marshals Auguste de Marmont and Édouard Mortier, duc de Trévise were following Napoleon's orders to move east toward Vitry. The evening of 23 March found the two marshals at Vertus and Étoges.[28] At Sézanne, Amey's 1,800 men found Michel-Marie Pacthod's 4,000-man division and a food convoy with 80 wagons. Hearing that a French corps was nearby, Pacthod and Amey decided to join forces with it. Their force reached Étoges on the evening of 24 March and sent messengers to Marmont and Mortier requesting instructions.[29]

In the Battle of Fère-Champenoise on 25 March 1814, 28,000 Allied cavalry inflicted a severe defeat on the forces of Marmont and Mortier,[30] which numbered 12,300 infantry, 4,350 cavalry and 68 guns. Due to inadequate reconnaissance, the two marshals unwittingly marched into the arms of Schwarzenberg and Blücher. According to George Nafziger, Pacthod and Amey had 5,800 men,[31] while Francis Loraine Petre estimated their force as 4,300 men.[32] After leaving Vatry, the force halted at Villeseneux to rest at 10:00 am when they were attacked by Fyodor Karlovich Korff's cavalry corps. With Amey's division formed into a single large square on the left (north) flank and 16 guns protecting the front, Pacthod's troops repulsed repeated attacks by Korff's horsemen for 90 minutes. They moved southwest to Clamanges where the convoy was abandoned and the horses used to help haul the cannons.[33] Pacthod's command reached Écury-le-Repos at 2:00–3:00 pm where it came under attack from the north by Ilarion Vasilievich Vasilshikov's cavalry corps and the southwest by Peter Petrovich Pahlen's cavalry corps. At the same time, Czar Alexander I of Russia directed the fire of 30 cannons from the south.[32]

When the badly beaten troops under Marmont and Mortier heard the approaching gunfire from Pacthod's fight, they believed that Napoleon was coming to save them. Though it was not true, this allowed the two marshals to rally their defeated troops. The Allies turned their attentions away from the two marshals and focused on the destruction of Pacthod's command. This probably saved Marmont and Mortier from total disaster.[34] At the end, 78 guns were blasting Pacthod's soldiers and the Allied cavalry finally broke all the French infantry squares.[35] With his troops still in a single square, Amey tried to get away into the Saint-Gond Marshes, but only a small handful of men escaped being killed, wounded or taken prisoner.[36] Pacthod, Amey and several brigadiers were captured and the czar released them on parole in recognition of their bravery.[35]

Restoration

Under the Bourbon Restoration, Amey was named a Chevalier of the Order of Saint-Louis in 1814 and appointed to command the 2nd Subdivision of the 2nd Military Division. On 4 March 1815, he attended a reception for Louis Antoine, Duke of Angoulême and his wife. A little over two weeks later he went over to Napoleon during the Hundred Days.[2] For this decision he was pushed into retirement on 9 September 1815. He returned to his hometown, serving as mayor of Sélestat in 1820–1830 and a member of the district council in 1826–1830.[1] He returned to the active list on 7 February 1831 and retired permanently from the army in 1833.[2] He died on 16 November 1850 at Strasbourg.[1]

Notes

- Kubler 1982.

- Mullié 1852.

- Jensen 2003.

- Broughton 2006.

- Phipps 2011, pp. 31–34.

- Clénet 1993, p. 152.

- Couteau-Bégarie & Doré-Graslin 2010, pp. 480–486.

- Chandler 2005, p. 237.

- Smith 1998, p. 224.

- Smith 1998, pp. 241–243.

- Smith 1998, p. 337.

- Oman 1996, p. 525.

- Oman 1996, pp. 57–58.

- Nafziger 1993.

- Leggiere 2007, pp. 102–103.

- Leggiere 2007, pp. 149–152.

- Leggiere 2007, pp. 153–156.

- Petre 1994, pp. 77–78.

- Smith 1998, p. 498.

- Nafziger 2015, p. 193.

- Nafziger 2015, pp. 617–618.

- Nafziger 2015, p. 289.

- Nafziger 2015, p. 629.

- Smith 1998, pp. 512–513.

- Petre 1994, p. 172.

- Petre 1994, p. 176.

- Petre 1994, p. 181.

- Petre 1994, pp. 185–186.

- Nafziger 2015, p. 335.

- Smith 1998, pp. 513–515.

- Nafziger 2015, p. 414.

- Petre 1994, p. 191.

- Nafziger 2015, p. 411.

- Nafziger 2015, pp. 409–410.

- Nafziger 2015, p. 413.

- Petre 1994, p. 192.

References

- Broughton, Tony (2006). "Generals Who Served in the French Army during the Period 1789-1815: Abbatucci to Azemar". The Napoleon Series. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- Chandler, David G. (2005). Jena 1806: Napoleon Destroys Prussia. Westport, Conn.: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 0-275-98612-8.

- Clénet, Louis-Marie (1993). Les colonnes infernales (in French). Perrin collection Vérités et Légendes.

- Couteau-Bégarie, Hervé; Doré-Graslin, Charles (2010). Histoire militaire des guerres de Vendée (in French). Economica.

- Jensen, Nathan D. (2003). "François-Pierre-Joseph Amey". FrenchEmpire.net. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- Kubler, Maurice (1982). "AMEY François Pierre Joseph". Nouveau Dictionnaire de Biographie Alsacienne (in French). Fédération des Sociétés d'Histoire et d'Archéologie d'Alsace. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- Leggiere, Michael V. (2007). The Fall of Napoleon: The Allied Invasion of France 1813-1814. Vol. 1. New York, N.Y.: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-87542-4.

- Mullié, Charles (1852). Biographie des célébrités militaires des armées de terre et de mer de 1789 a 1850 (in French). Paris.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Nafziger, George (1993). "French Grande Armée, 1 August 1812" (PDF). United States Army Combined Arms Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 December 2011. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

- Nafziger, George (2015). The End of Empire: Napoleon's 1814 Campaign. Solihull, UK: Helion & Company. ISBN 978-1-909982-96-3.

- Oman, Charles (1996) [1908]. A History of the Peninsular War Volume III. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole. ISBN 1-85367-223-8.

- Petre, F. Loraine (1994) [1914]. Napoleon at Bay: 1814. London: Lionel Leventhal Ltd. ISBN 1-85367-163-0.

- Phipps, Ramsay Weston (2011) [1931]. The Armies of the First French Republic: Volume III The Armies in the West 1793 to 1797 And, The Armies In The South 1793 to March 1796. Vol. 3. USA: Pickle Partners Publishing. ISBN 978-1-908692-26-9.

- Smith, Digby (1998). The Napoleonic Wars Data Book. London: Greenhill. ISBN 1-85367-276-9.