Francis Childs (printer)

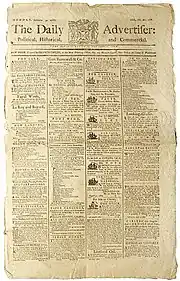

Francis Childs (1763–1830) was an American publisher and printer of The New York Daily Advertiser, founded on Thursday, March 1, 1785, who went on to be one of the printers for the newly established United States government. Childs, together with John Swaine, both established printers in New York City, printed the laws of the United States, beginning in 1789 shortly after the Constitution was ratified. They also published several works of the first Congress which met in 1791, in New York City.[1][2]

& John Swaine, 1791

Printing career

Childs was the printer and publisher of The New York Daily Advertiser, the third daily newspaper paper to appear in the United States.[3] Its first issue was published on Thursday, March 1, 1785 with its final issue appearing on August 30, 1806.[4] Since it was an independent upstart newspaper it realized a low subscription rate in its early days and attracted few advertisers. In an earnest effort to attract more advertising, Childs sold advertising space at the low rate of three shillings per ad.[3] During the ratification debates over the proposed United States Constitution in 1788 and 1789, The New York Daily Advertiser featured essays, which came to be known as The Federalist Papers, in support of that constitution.[5]

In a letter from Alexander Hamilton to Francis Childs' and The New York Daily Advertiser, dated July 12, 1787, Hamilton pointedly criticized New York Governor George Clinton for his opposition to the ratification of the proposed United States Constitution.[6] On September 15, 1787, Hamilton again wrote to The New York Daily Advertiser in regards to a defense of Clinton which appeared in the July 21 issue of The Advertiser and the September 6 issue of The New-York Journal, and Weekly Register, where he continued his criticism of Governor Clinton. In this letter Hamilton referred to himself in the third person, but left instructions to Childs to reveal his name to anyone making inquiries as to the letter's author on behalf of the governor.[7] Revolutionary poet Philip Freneau wrote political editorials for The New York Daily Advertiser, even though he was not its editor and an anti-federalist.[3]

In the 1780s before Childs began printing for the government, he worked with Benjamin Franklin in Philadelphia helping him set up his national network of printers.[8]

Official government printer

After ratification of the United States Constitution on June 21, 1788 the competition over the public printing contract for the newly established government became stringent among the leading printers in New York. Along with Childs, there was Samuel Loudon, Thomas Greenleaf, Archibald McLean, and John Fenno who all submitted applications for this important contract.[9][10] Childs and Swaine submitted a joint petition to the House of representatives on May 15, 1789 and were awarded the contract. On June 9, 1789, Childs and Swaine jointly addressed Samuel Allyne Otis, Secretary of the United States Senate, and John J. Beckley, Librarian of the United States Congress, as follows: "We will engage to print the Laws of Congress on the following terms": "For every sheet of letter press, including six hundred copies, two dollars and a half," "The paper to be furnished at the expense of the United States". The Secretary of the Senate and the Clerk of the House signed an agreement on June 29 that Childs and Swaine were to be jointly employed in the printing of the Laws of Congress. On July 2 Childs and Swaine were also commissioned "to print the laws of the United States until further order of Government". Their printing contract with the government was promptly announced in the July 3 issue of their newspaper, The New York Daily Advertiser: ""Gentlemen who wish to be supplied with copies of the Laws of the United States, are requested to make their application to Francis Childs and John Swaine, printers in New York, who are entrusted, by Congress, with the printing of the same". The price of the laws was set at one dollar. The laws were to be printed on "fine paper and a new type".[11]

Legal works printed

- Journal of the House of Representatives of the United States, 1789[12]

- Laws passed in the Territory of the United States North-West of the River Ohio, 1791[13]

- Report of the Secretary of State, on the subject of the cod and whale fisheries[14]

- Report of the committee appointed to examine into the state of the Treasury Department, 1794[15]

- An act providing for the relief of such of the inhabitants of Saint Domingo, resident within the United States, 1794[16]

- An act for the remission of the duties arising on the tonnage of sundry French vessels which have taken refuge in the ports of the United States, 1794[17]

See also

Citations

- Lee, 1923, p. 120

- Open Library

- Lee, 1923, p. 120

- Indiana University: Indiana University Library Catalog

- Hudson, 1873, p. 179

- Letter, Alexander Hamilton, July 21, 1787

- Letter: Alexander Hamilton, September 15, 1787

- Frasca, 2004, p. 404

- Letter: Loudon to Hamilton, May 22, 1789

- Acts of the First Congress, 1789

- Childs, 1962, pp. 95–97

- Journal, House of Representatives, U.S., 1789, p. title page

- Laws, U.S. Territory, North West, 1791, p. title page

- Report, Secretary of State, cod and whale fisheries, 1791, p. title page

- Report, Committee, Treasury Department, 1791, p. title page

- Act relief, Saint Domingp, 1794, p. title page

- Acts...tonnage of French Vessels...in the United States

Bibliography

- Childs, James B. (1962). "Disappeared in the Wings of Oblivion": The Story of the United States House of Representatives Printed Documents at the First Session of the First Congress, New York, 1789". The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America. The University of Chicago Press. 58 (2): 91–132. doi:10.1086/pbsa.58.2.24300895. JSTOR 24300895. S2CID 159967468.

- Frasca, Ralph (Autumn 2004). "Benjamin Franklin's Printing Network and the Stamp Act". Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies. Penn State University Press. 71 (4): 403–419. JSTOR 27778636.

- Hamilton, Alexander (July 21, 1787). "From Alexander Hamilton to The Daily Advertiser, [July 21, 1787]". Letter to The New York Daily Advistiser. National Archives. Retrieved March 8, 2022.

- Hamilton, Alexander (September 15, 1787). "From Alexander Hamilton to The Daily Advertiser, [September 15, 1787]". Letter to The New York Daily Advistiser. National Archives. Retrieved March 8, 2022.

- Hudson, Frederic (1873). Journalism in the United States, from 1690 to 1872. New York, Harper & Brothers.

- Jefferson, Thomas (1791). Report of the secretary of state, on the subject of the cod and whale fisheries. Philadelphia : Printed by Francis Childs and John Swaine.

- Lee, James Melvin (1923). History of American journalism. Boston, New York, Houghton Mifflin Company. ( Alternative publication )

- Loudon, Samuel (1789). "To Alexander Hamilton from Samuel Loudon, 22 May 1789". National Archives: Founders Online. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- Miller, John Chester (1960). The Federalist era, 1789–1801. New York, Harper. ISBN 978-0-0613-30278.

- "Printed by Francis Childs, printer of the laws of the United States". OPen Library. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- "ACTS PASSED AT THE FIRST CONGRESS & other publications by Francis Childs & John Swaine". Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- Laws passed in the Territory of the United States North-West of the River Ohio. Philadelphia : Printed by Francis Childs and John Swaine. 1791.

- Report of the committee appointed to examine into the state of the Treasury Department. Philadelphia : Printed by Francis Childs and John Swaine. 1794.

- An act providing for the relief of such of the inhabitants of Saint Domingo, resident within the United States. Philadelphia : Printed by Francis Childs and John Swaine. 1794.

- Journal of the House of Representatives of the United States. New York : Printed by Francis Childs and John Swaine. 1789.

- The Daily Advertiser. Indiana University: Indiana University Library Catalog. 1787. Retrieved March 8, 2022.

- An act for the remission of the duties arising on the tonnage of sundry French vessels which have taken refuge in the ports of the United States. Philadelphia : Printed by Francis Childs and John Swaine. 1794.