Francis Drake's circumnavigation

Francis Drake's circumnavigation, also known as Drake's Raiding Expedition, was an important historical maritime event that took place between 15 December 1577 and 26 September 1580. The expedition was authorised by Queen Elizabeth I and consisted of five ships led by Francis Drake. Termed a 'voyage of discovery', it was in effect an ambitious covert raiding voyage and the start of England's challenge to the global domination of Spain and Portugal.[1]

| Francis Drake's circumnavigation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Anglo–Spanish War | |||||||

Engraved world map of Drake's circumnavigation | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Various ports & shipping |

5 ships 169 men and boys | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

13 ships captured & plundered 12 merchants ships run aground 5 settlements plundered |

1 ship lost 2 ships scuttled 103 dead | ||||||

Drake set off on 15 December 1577 after a delay of nearly six months. After capturing Spanish vessels and Portuguese caravels while crossing the Atlantic he passed Cape Horn and became the first Englishman to navigate the Straits of Magellan. After reaching the Pacific Ocean in October 1578, he sailed up the west coast of South America. Due to losses by storms and disease, only two ships remained, one of which was the Golden Hind. Drake then plundered Spanish ports and took a number of Spanish treasure ships including the rich galleon Nuestra Señora de la Concepción. After continuing north, hoping to find a route back across to the Atlantic, Drake sailed further up the west coast of America than any European ever had done, and landed in present-day California, claiming the land for England and naming it New Albion.

Unable to find a passage, Drake turned south in the lone Golden Hind and in July 1579 sailed west across the Pacific. His travels took him to the Moluccas, Celebes, Java, and then round the Cape of Good Hope and finally the western tip of Africa. Drake arrived back in England in September 1580 with a rich cargo of spices and treasure and the distinction of being the second man to circumnavigate the globe and the first Englishman to do so. Seven months later, Queen Elizabeth knighted him aboard the Golden Hind, much to the annoyance of King Philip II of Spain because of his piratical actions. As a result, the voyage was one of the precursors to the Anglo–Spanish War.[2] Drake's intrusion into the Pacific, which Spain considered Mare clausum,[3] triggered an immediate Spanish colonization attempt of the Strait of Magellan aimed to block access to the Pacific.[4][5]

Background

During the early stages of the Age of Discovery, the Treaty of Tordesillas divided the New World into Spanish and Portuguese zones and was signed by the nations' respective monarchs and Pope Alexander VI. However the Protestant Reformation in the early sixteenth century resulted in Protestant nations of Europe that did not recognise Papal spiritual or temporal authority and subsequently rejected the treaty. One of these nations was England, and in the 1560s, King Philip II of Spain's relations with Queen Elizabeth I of England deteriorated, following her restoration of royal supremacy over the Church of England through the Act of Supremacy in 1559.[6]

English merchants and adventurers subsequently engaged in trade missions with the various Spanish posts in the New World. Spain was deeply suspicious of any attempt by foreign powers to trade or establish colonies in their zone of control, going so far as to massacre several hundred French Huguenot inhabitants of Fort Caroline in French Florida in 1565 after they had surrendered.[7]

In 1567, a fleet led by the English privateer Sir John Hawkins conducted a slave trading voyage, transporting enslaved Africans across the Atlantic to sell in Spanish and Portuguese colonies in the Americas. Sir Francis Drake, a cousin of Hawkins, accompanied him on the expedition. A number of ships were lost however when they were attacked by a Spanish squadron at the Battle of San Juan de Ulua. As a result, the Spanish became a lifelong enemy for Drake and they in turn considered him a pirate.[8]

Drake subsequently made two profitable trading voyages to the West Indies in 1572, commanding two vessels in a marauding expedition against Spanish ports in the Caribbean. He saw the Pacific Ocean and captured the port of Nombre de Dios on the Isthmus of Panama. He returned to England with a cargo of Spanish treasure but came at a tense time due to Elizabeth and Philip both agreeing and signing the Convention of Nymegen in 1573. Drake as a result had to lay very low over the next few years but intended on another future expedition where he knew he could get backing. With nearly 100,000 pesos of stolen loot secretly hidden away, Drake had enough money to command and set up a new fleet with a return to the Spanish Main. He also started to build a new more sturdy and heavily armed ship for the voyage.[9]

Preparation

In 1577, Drake was secretly commissioned by Queen Elizabeth I to set off on an expedition against the Spanish colonies on the American Pacific coast. The Queen invested 1,000 crowns in the venture and so Drake became a privateer.[10] The expedition also intended to explore areas where there could be potential English settlement – the first of its kind. Elizabeth and members of her court, including Robert Dudley, Christopher Hatton and Francis Walsingham (now Elizabeth's Secretary of State) were among those who invested in Drake's voyage and secretly supported his privateering – the looting of Spanish ships and ports. Other prominent members were Clerk of the Queen's ships – George Wynter, Surveyor of the Navy – William Wynter and Sir John Hawkins.[11]

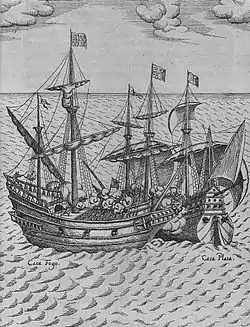

Drake set up the fleet over the year – the command ship and one that Drake had finished building was the Pelican, Its design being based on the Biscayan built nao Victoria,[12] the first ship to circumnavigate the world. It was 150 tons and was the most powerful ship of the expedition with eighteen guns in total. Of these seven were demi-culverins each side and two disassembled pinnaces. This was to be assisted by four other ships; Elizabeth of eighty tons with sixteen guns and was captained by John Wynter,[13] Marigold a thirty-ton supply ship of ten guns captained by John Thomas and two supply ships Benedict and the Swan. In all the complement consisted of roughly 164 men in total. The ships were armed and equipped with care and sufficiency.[14]

One essential member of crew was Diego, a formerly enslaved African who escaped from the Spanish and had joined Drake at Nombre De Dios in 1572.[15] Diego, by then a free man, was also a capable ship builder and knew the trade having been employed in Drake's service. Diego's fluency in Spanish and English however would make him a useful interpreter when Spaniards or Spanish-speaking Portuguese were captured. He was employed as Drake's servant and was paid wages, just like the rest of the crew.[16] As a free man he would accompany Drake assisting with local knowledge, but crucially, Drake through Diego would intend to feed false intelligence to the Spanish.[17]

There were also 'gentlemen' adventurers all of whom were linked to the investors. One of these was Thomas Doughty, an attorney who had accompanied Drake on his previous voyage, although tensions between the two became apparent. Drake also had his younger brother Thomas and his cousin John to accompany him. In addition to this there were carpenters, a blacksmith, a botanist and several musicians to entertain the captain and crew, and Walsingham sent his chaplain and confidant Francis Fletcher as an observer.[18]

Drake used the only means of what the globe looked like and at the time that was from the Flemish cartographer Abraham Ortelius's map Theatrum Orbis Terrarum.[19] Rather than reveal his true intentions, Drake told the crew they were embarking on a trading voyage to Levant. The reason for this was to persuade the men to take ship and to avoid knowing the real dangers they faced.[20]

| Name | Captain | Crew | Weight (tons) | Fate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pelican (Golden Hind) | Francis Drake | 80 | 160 | Completed voyage |

| Elizabeth | John Wynter | 45 | 80 | Deserted off Cape Horn and returned home. |

| Marigold | John Thomas | 25 | 30 | Lost with all hands off Cape Horn |

| Benedict (supply) | Thomas Moon | Exchanged for Christopher | ||

| Swan (supply) | John Chester | scuttled | ||

Drake and the fleet set out from Plymouth on 15 November 1577, but soon encountered a storm in the English channel. Attempting to head back to port, they were too late – Pelican and Marigold suffered serious damage to their masts. They were forced to take refuge in Falmouth, from there they returned to Plymouth for repairs which lasted nearly a month.[21]

Circumnavigation voyage

They finally left Plymouth on 13 December heading South into the Atlantic, but poor winds led them to their first port of call two weeks later at Mogador off Morocco. Whilst assembling a Pinnace there Drake lost a man to Moorish raiders. Setting off again he sailed past the Canary Islands where the fleet captured three Spanish fishing vessels and three Portuguese caravels. The Benedict was swapped for one of the bigger Spanish vessels; a fifty-ton ship which was renamed Christopher, the Benedict itself was released with the prisoners.[22]

Atlantic crossing

In January 1578 Drake then set off for the Portuguese Cape Verde Islands hoping for plunder and supplies. Stopping at Santiago island he encountered the Santa Maria, a Spanish merchant ship which he captured despite coming under fire from a fort's guns just off Praia. The ship was loaded with wine and other stores, and was renamed Mary. Drake used the ship's haul of useful Spanish maps but more importantly added a Portuguese navigator Nuno da Silva, a man with considerable experience navigating in South American waters and who was willing to help Drake.[14] Drake assumed command of the Mary and reassigned Doughty to command his flagship the Pelican and set the captive Spanish crew off in a pinnace. Later tension between Drake and Doughty however turned sour when the latter accused Drake's brother, Thomas of stealing from the captured cargo of wine.[22]

During the long voyage across the Atlantic, Drake's hostility increased, fuelled by the rancour of his brother. As a result, Drake eventually demoted Doughty to command of the Swan. This insult proved too much for Doughty to take, and he began to complain bitterly about "the Captain General".[23]

Rounding South America

After passing the coast of Portuguese Brazil, Drake's fleet suffered great attrition after storms twice scattered the fleet; so on 13 May Drake put in to a bay and anchored off Cape Tres Puntas in the San Jorge Gulf. Another storm blew up and the fleet once more were forced to run for the open sea. When the Swan became separated from the rest of the fleet during a severe storm, Drake became convinced that Doughty was practicing witchcraft and this became somewhat of a bad superstition amongst the crew.[24]

On 17 May the fleet anchored in Deseado in order for the other ships to catch up, and over the next few days the fleet was brought together except the Swan under Doughty. They turned up the following day to meet a seething Drake where they had another quarrel, the former accusing him of witchcraft which he vehemently denied. Decisions were made regarding the fleet – Drake realised the need to condense his force due to losses sustained from disease and storms from the Atlantic crossing. The decision was made to scuttle Swan – the resultant loss of his command enraged Doughty. He confronted Drake who promptly lost his temper, struck Doughty and ordered him bound to the mast. It was decided that the ex Spanish Christopher was no longer needed so was burned, and so only the rigging and ironwork was kept.[25]

Execution of Doughty

By 3 June both Doughty and his brother, John who had been defending him had been put under house arrest and the sailors were forbidden from interacting with them. Drake accused Doughty of being "a conjurer and a seditious person", and his brother of being "a witch and a poisoner".[26]

The English made landfall on the bay of San Julian a natural harbour in Patagonia. Ferdinand Magellan had called in the same place half a century earlier, where he put to death some mutineers. Drake's men saw weathered and bleached skeletons on the grim Spanish gibbets and decided to remain in San Julian for the winter before attempting the Strait of Magellan.[27]

Whilst in San Julian Drake finally made the decision to try Doughty with treachery and an incitement to mutiny. The main pieces of evidence against Doughty were the testimony of the ship's carpenter, Edward Bright, who after the trial was promoted to master of the ship Marigold, and Doughty's admission of telling Lord Burghley, a vocal opponent of agitating the Spanish, of the intent of the voyage. Drake consented to his request of Communion and dined with him along with Francis Fletcher who had this strange account:

And after this holy repast, they dined also at the same table together, as cheerfully, in sobriety, as ever in their lives they had done aforetime, each cheering up the other, and taking their leave, by drinking each to other, as if some journey only had been in hand.[28]

The trial eventually found Doughty guilty, but only on the mutiny charge. On 2 July, at Drake's insistence, Doughty was beheaded, but this stern example did not have the desired effect. Drake held up his severed head and stated, 'behold the head of a traitor'. Increasing tensions between mariners and the gentlemen explorers brought the prospect of mutiny and this would last nearly a month. Drake went one step further and used a sermon to make a speech laying down rules of conduct, with himself in sole command. The effect on the assembled crew was powerful and from then mutiny was never on the mind of anyone.[29]

After attempts to repair Mary it was discovered that she had rotting timbers, so they broke up the ship for parts. In August they set off sailing West and then went on an attempt to pass through the Strait of Magellan.[30]

Strait of Magellan

Prior to entering the Strait, in July 1578, Drake sent Wynter ashore where he learned from indigenous people that they ate the astringent bark Winter's bark.[31] Captain Wynter ordered the collection of great amounts of bark – hence the scientific name.[32] Drake renamed the Pelican as the Golden Hind on 20 August 1578[33] to honour his patron, Sir Christopher Hatton, whose family crest was a golden hind (female red deer). Drake passed through the Strait of Magellan in just 16 days. As soon as they entered the Pacific Ocean, violent storms nearly shattered the remaining ships. The Marigold was never seen again and was presumably lost with all hands. A week later, the Elizabeth became separated from the Golden Hind and was battered to the point that the crew demand they head for home. Wynter, hopeful that he would meet the other ships in turn, demanded that he sail on to the East Indies and rendezvous with Drake. Fearing an all out mutiny, he reluctantly headed back to England.[34]

The fleet now only composed the Golden Hind with less than half of the 170 men that had set out. He sailed on to Tierra Del Fuego and arrived at one of the islands there. In the Magellan Strait Francis and his men engaged in skirmish with local indigenous people, becoming the first Europeans to kill indigenous peoples in southern Patagonia.[32]

After this passage, the Golden Hind was pushed south and discovered an island which Drake called Elizabeth Island. Drake, like navigators before him, probably reached a latitude of 55°S (according to astronomical data quoted in Hakluyt's The Principall Navigations, Voiages and Discoveries of the English Nation of 1589) along what is now the Chilean coast. Despite popular lore, it seems unlikely that he reached Cape Horn or the eponymous Drake Passage, because his descriptions do not fit the first, and his shipmates denied having seen an open sea. The first report of his discovery of an open channel south of Tierra del Fuego was written after the 1618 publication of the voyage of Willem Schouten and Jacob le Maire around Cape Horn in 1616.[35]

Mocha Island and the Mapuche

The Golden Hind sailed north along the Pacific coast of South America – his first port of call was Mocha Island to get food and water. They encountered the Native Mapuche and greeted them with pleasantries the feelings of which were mutual. The first day proved to be a success with the Mapuches bringing a number of sheep, chickens and wheat to the crew. On the second day an eleven-man boat came ashore for water but the reception turned hostile; they were set upon and the Mapuche killed two and captured two more. A number were wounded including Diego and Drake who both had a large number of arrow wounds; Drake had one in the face. They withdrew but according to Fletcher, the fate of the two captured was death in ritual cannibalism being slowly carved into pieces and eaten alive.[16][36][37]

Diego never fully recovered from his many wounds. A year later, when the expedition neared the Moluccas, he died, perhaps from a lingering infection. Drake regretted the loss of his servant and his skill, diplomacy and knowledge of South America.[15]

Raids on Spanish American west coast

Heading further North, Drake recovered from his wounds and spent many weeks observing for settlements to raid.

Valparaíso and Callao

On December 5 he viewed the small Spanish settlement of Valparaíso, a coastal town with a number of houses and a church. He made an assault on the town and plundered what he could find, such as valuable art treasures and the church silver. Its harbour contained a ship which proved the most valuable as it was full of Chilean wine, 25,000 pesos in gold and with charts of the South American coast.[38] Drake's sack of Valparaíso gave origin to the legend about Cueva del Pirata.[39]

Drake left and carried on Northwards up the coast. He sailed into the remote Salada Bay near Copiapó where he was able to careen his ship and assembled the Golden Hind's pinnace. Whilst here Drake attempted to wait for the Elizabeth to appear which would've given sufficient strength to attack Panama, the next target. When it became apparent that Elizabeth wasn't going to turn up, Drake sailed off once the pinnace had been completed.[40]

Just before they got to Callao a Spanish coaster was intercepted and captured; from the prisoners information was gained bearing news that a number of treasure ships were heading in the area. As a result, Drake entered Callao which was the harbour for Lima on 13 February. The English took the town with ease and in the harbour lay a dozen vessels which Drake ordered ransacked and run aground. They then questioned the inhabitants from whom they learnt that a large treasure galleon called Nuestra Señora de la Concepción, had recently departed North West towards Panama bearing a valuable cargo of silver with its final destination of Manila. The following day an excited Drake rushed off in pursuit with the recently built pinnace and headed to the direction where the Spanish treasure galleon was most likely to be intercepted.[41]

Spanish pursuit

Around the same time the Spanish authorities began getting reports that an English naval force was off the coast. Panic began to spread once news that settlements had been raided. In Lima the Viceroy of Peru Francisco de Toledo was shocked and was surprised that the English had got this far. He immediately ordered all ships to be repaired and re floated from Callao to pursue but none were equipped to challenge Golden Hind. A dispatch was also sent off to Lima calling for more troops, and two ships were chosen for the chase. Frias Trejo commanded the Nuestra Señora del Valle and Pedro De Arana in the Nao de Muriles. These two were however improperly ballasted and so returned to port despite both being in sight of Drake. Toledo furiously ordered his own son Luis to lead the expedition with two heavily armed galleons and eleven other vessels to capture any English vessel they came across. They also were given the best pilots in the region including Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa and 120 soldiers.[42]

The fleet left Callao on 27 February and set out in pursuit of the English who they thought were heading towards Panama where Gamboa thought Drake would strike next.[43]

Drake still in pursuit of the Nuestra Señora de la Concepción and unaware of the sizeable Spanish force now coming for him, took a small ship just having departed from Guayas River which led to Guayaquil. The ship belonged to Benito Diaz Bravo and in its hold contained nearly 20,000 gold pesos from the Zaruma gold mines along with other victuals.[44]

Capture of Spanish treasure ships

On 1 March Drake sighted the Nuestra Señora de la Concepción just off the Audiencia of Quito coast. Drake came across the slower moving galleon then moved the pinnace towards the Spanish ship's port. The Spanish captain Juan de Anton was surprised to see a foreign vessel out this far. Drake ordered Diego to demand in Spanish for their sails to strike. Anton however refused and so Drake answered with cannon and arquebus fire. No further answer came from the Spaniard so more cannons were fired, this time damaging Nuestra Señora de la Concepcións rigging and also tore the mizzenmast and lateen yard off. Then with the Golden Hind on one side and the pinnace on the other, the English closed in and were able to board the vessel.[45] Since they were not expecting English ships to be in the Pacific, Nuestra Señora de la Concepcións (which later become known as Cagafuego's) crew was taken completely by surprise and surrendered quickly and without much resistance. Once in control of the galleon, Drake brought both ships to a secluded stretch of coastline to unload the treasure.[46]

Such was the hoard, it took six days for the treasure to be unloaded. Aboard the Nuestra Señora de la Concepción, Drake discovered 36 kilograms (80 lb) or 13 chests full of royals of plate and 26 thousand kilograms (26 long tons) of silver. 25,000 pesos of amounting in value to 37,000 ducats. In addition a golden crucifix and jewels completed the total worth around 360,000 pesos (about £7m by modern standards). In total the treasure amounted to the equivalent to around £480m in today's terms. There was so much treasure that the silver bars replaced the Golden Hind's ballast.[47] The crew could not believe their luck and were overjoyed at the sight of the Spanish galleon's treasure, and their morale reached a new high. Drake was also pleased at his good luck, and he showed it by dining with Cagafuego's officers and gentleman passengers. He offloaded his captives a short time later, and gave each one gifts appropriate to their rank, as well as a letter of safe conduct. Through Diego, Drake was able to bluff the Spanish and made it clear that there were other English ships in the area such as the Elizabeth under John Wynter (even though he had returned home) in order to cause some kind of panic and confusion and lead the Spanish into a wild-goose chase.[46]

On 16 March Luis de Toldeo and Gamboa sailed into Manta to gather any information they could get on Drake. They were told about Drake's pursuit of the Nuestra Señora de la Concepción and it was soon realised the inevitability that Drake had captured the ship. Gamboa nevertheless had a plan that if Drake was loaded with treasure, he would be able cut him off before he would get to the coast of the Province of Nicaragua. Don Luis however proposed to go to Panama in order to carry on his voyage and deliver his father's vital report regarding the English discovery of the Spanish settlements in South America.[48]

Meanwhile, Drake went further north along the South American coast. Coming across Cano island Drake captured a frigate carrying a cargo of maize, honey and sarsaparilla. Drake took the vessel to a nearby bay (Bahía Drake); here the Golden Hind was repaired and careened. Drake decided that the enormous haul of treasure in the Golden Hind needed to be transferred to lighten his ship if he was to carry on any further. At the island they moved part of the silver over to the captured frigate which proved a sturdy ship. The frigate was also armed by a number of the Golden Hinds' guns.[49] Drake sent a party with the pinnace to forage and refill their water casks. As they moved into the dense tropical rain forest they managed to kill a crocodile and a monkey which they brought back to the ships. This was the first time they had tasted meat for some time. At the same time the English felt a 'severe shake' despite being a mile offshore – it was in fact their first experience of a violent earthquake – and some of the crew even witnessed what was a tsunami on the nearby shore.[50]

Whilst the Golden Hind was being repaired, the pinnace was scouting the area and came across another Spanish vessel which was soon captured with only a shot fired – this time a small barque. Although there was little value in the hold, the English did capture two valuable rutters which showed in detail the Manilla-Acapulco route. Also on board were two Chinese pilots who knew the route across the Pacific. Drake then disposed of the Sarsaparilla (the crew reported this as being an 'unpleasant smell'), and set off in the last week of March intending to raid the town of Guatulco.[49]

Last raids

Drake then raided the settlements of El Realejo and Sonsonate finding little of value.[51] At Guatulco the English went ashore against little resistance and promptly sacked the place. The booty was considerable; a heavy golden chain along with 7,000 pesos in silver was looted. There were plenty of provisions like water casks and food which the crew desperately needed but also fine China and silks, more maps of the Manilla galleon route and a number of slaves. Drake stayed for a couple of days, following which he released all the Spanish captives. The Portuguese pilot Nuno da Silva was also released here; he had gone beyond his usefulness having little to no knowledge beyond the Magellan straits.[52] He was also told that he was to give false information to the Spanish in a double bluff in that Drake had intended to go home via the Northwest Passage. Guatulco would prove to be Drake's last raid on the West Coast of New Spain.[53]

Nuno da Silva was later questioned by the Spanish in regards to Drake's whereabouts – he was tortured and interrogated, giving the information that Drake wanted them to hear, in that he was heading for the Northwest passage. The Spanish however did not believe this as Drake had actually hoped. At the same time the Spanish pursuit was going nowhere, having caught no sight of any English ships.[53] In the end Toledo had no real desire to overtake Drake who they thought must be much further North. Toledo proceeded to Panama where the 'pursuit' ended. Nevertheless, the Spanish continued to guard the routes where they thought Drake would turn around to head back via the Straits of Magellan.[19]

California and Pacific North West

Drake sailed north to seek a shortcut back to England via the hypothetical Strait of Anián, a supposedly navigable shortcut connecting the Pacific and Atlantic. The strait was speculated to exist at about 40 degrees north.[54]

In May Drake's two ships passed the Baja Peninsula and continued North. Prior to Drake's voyage, the western coast of North America had only been partially explored in 1542 by the Spanish explorer Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo. Intending to avoid further conflict with Spain, Drake navigated northwest of Spanish presence. By navigating well beyond where Cabrillo had asserted Spanish claim in the Pacific Northwest, Drake searched for a suitable bay to repair and careen his ship for the journey back to England.[21]

On 5 June 1579, the ship briefly made first landfall at South Cove, just south of Coos Bay or at Whale Cove near Depoe Bay and gathered fresh water and food. Although Drake may have possibly reached a latitude as high as 48 degrees, his northward progress was ultimately stopped by foul weather in the northeast trade winds belt. Upon failing to locate the strait, Drake went no further North and instead headed back south.[55]

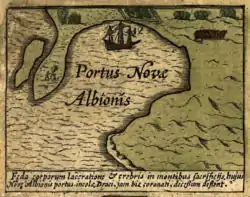

Nova Albion

On 17 June, as Drake headed South, his crew found a protected cove and landed on the coast of what is now Northern California. After staying there for twelve days Drake set off again and landed somewhere north of Spain's northernmost claim at Point Reyes, in Alta California. He found a good bay and landed in an estuary which became known as Drakes Estero. After erecting a small wooden fort and tents ashore, the crew restocked the two ships then stayed for a time to repair and careen the two ships.[56]

Drake also met the Native Coast Miwok people and soon had friendly interactions with them exchanging gifts while the English were given food.[57] In a particularly significant gesture, a large assembly of Coast Miwok descended on the encampment and honoured Drake by placing chains around his neck, a sceptre in his hand, and a crown of feathers on his head as if he were being proclaimed king. Upon this uncertain, seemingly voluntary surrender of sovereignty by its owners, England based its presumed legal authority to the territory.[58] Drake thus claimed the land in the name of the Holy Trinity for the English Crown as called Nova Albion – Latin for "New Britain" and for Queen Elizabeth I. Drake chose this particular name for two reasons: first, the white banks and cliffs which he saw were similar to those found on the English Channel coast and, second because Albion was an archaic name by which the island of Great Britain was known. To document and assert his claim, Drake is said to have an engraved Drake's Plate of Brass, one which contained a sixpence bearing Elizabeth's image, attached to a large post. Giving details of Drake's visit, it claimed sovereignty for Elizabeth and every successive English monarch.[59]

After gaining the Coast Miwok's trust, Drake journeyed to explore the inland area and visit their villages. Accompanied with crew members, Drake trekked on a Coast Miwok trail to traverse the Inverness Ridge and descend into what is now the Olema Valley.[56] Francis Fletcher observed and wrote in detail regarding the wildlife, countryside and climate. He wrote in great detail on the Coast Miwoks themselves in day-to-day activities being the first person to make a written record of any of the 64 distinct language groups in prehistoric California.[60]

After staying on this particular stretch of coast for several weeks the English were ready for the return voyage, and decided to leave the Spanish frigate behind in the bay. Overall, the relations between the Coast Miwok and their visitors were peaceful and friendly. When Drake and the crew left New Albion on 23 July, the Miwok seemed to exhibit distress when Golden Hind sailed away.[61]

Drake paused his journey the next day when anchoring his ship at the Farallon Islands where the crew hunted seal meat.[62] Assertions that he left some of his men behind as an embryo "colony" are founded on the reduced number who were with him in the East Indies.[63]

Detail of Jodocus Hondius map of 1589 showing cove in New Albion visited by Francis Drake.

Detail of Jodocus Hondius map of 1589 showing cove in New Albion visited by Francis Drake. Drake's landing in California, engraving published 1590 by Theodor de Bry

Drake's landing in California, engraving published 1590 by Theodor de Bry Natives of California greet Sir Francis Drake

Natives of California greet Sir Francis Drake

Pacific and East Indies

On 23 July 23 the Golden Hind left New Albion and two days later they sailed west to continue their Pacific crossing.[61] Winds were good enough to carry the ship roughly South West to the Caroline Islands by 13 October, an unusually quick passage at the time.[64] After staying at either Yap or Palau for two days they were met with some hostility from the natives who came in canoes in the hundreds. This led to some trouble and fearing being overwhelmed the English fired a number rounds killing or wounding some twenty before sailing off.[65]

A week after the encounter a Portuguese carrack was sighted. Drake intended to capture the vessel and so a running battle ensued until the carrack moved in amongst some shoals. Drake with his ship heavily laden with goods dared not enter for fear of running aground and so veered off continuing Westwards.[66]

Moluccas and Celebes

Drake having sailed past Mindanao soon reached the Moluccas. These were a group of islands in the south west Pacific known as the 'Spice Islands' for its rich plantations of nutmeg and cloves. Drake was cautious about meeting further Portuguese trading settlements, but he was in luck – by mid 1575 most of the Portuguese positions in the Moluccas had already fallen to the natives of the islands. In addition the indigenous tribes or kingdoms that had supported the Portuguese had been virtually cornered.[61]

In early November 1579, having passed Siau Island, Drake encountered two fishing canoes who were able to guide the Golden Hind through the islands. They led him to the island of Ternate – its volcanic peak Gamalama dominating the skyline. There Drake was able to dock and the crew were warmly welcomed by Sultan Babullah in a ceremonious courtesy in an old Portuguese castle. The Sultan controlled a number of other islands in addition to Ternate and traded mostly in cloves. Drake proclaimed himself no friend of the Portuguese and expressed an interest in trading for spices.[65]

After the first round of negotiations, Babullah sent a sumptuous meal to Drake and his men: rice, chicken, sugarcane, liquid sugar, fruit, coconuts and sago. Drake was impressed with Babullah, noting the enormous respect that he enjoyed from his subjects but could not fulfil on any agreements. In particular he resisted invitations to join in a campaign against the last remaining Portuguese fort in Tidore since his mission was to get back to England as soon as possible and fulfil his mission. With English linen, gold and silver, Drake was able to trade for around ten tonnes of exotic spices – most of these were cloves but included ginger, black pepper and nutmeg. With so many cloves on board that were worth so much – Drake rewarded his crew with silver which boosted their morale. The Golden Hind stayed for a further five days before sailing away.[67]

Drake sought a place to trim and water his ship and soon arrived off the Celebes islands unaware of the dangerous shoals and subsequently became caught on a reef on 8 January 1580.[68] Here Fletcher came at odds with Drake – in a sermon he preached regarding the grounding, Fletcher suggested that their ships' recent woe had resulted from the execution of Doughty which Drake promptly claimed as unjust. After the sermon, Drake had Fletcher chained to a hatch cover, then "solemnly excommunicated him".[69] The sailors waited for expedient tides and soon dumped three tons of cargo (mostly cloves) and a number of guns – this eventually freed the ship after three days much to the crew's and Drake's relief. As they left they were driven southeastwards into the Banda Sea and refitted at either Damer or Romang island to trim and careen Golden Hind.[70]

Java

The next month was frustrating for Drake – bad weather and confusing seas of the East Indies meant going was tough. They slowly made their way into the Savu Sea westwards passing the northern coast of Timor. On March 11, they eventually touched down at Tjilatjap on Java having anchored a safe distance from land. A boat load of armed men came ashore and were well received by the locals who showed them where to find water and food. Following this Drake then made contact with the rajahs and soon began exchanging courtesies and commodities.[71] The latter only wanted the finest silks and of which Drake had plenty from what they had taken at Guatulco. They stayed for two weeks and gathered enough supplies namely rice, chickens, yams and dried beef for part of the journey back.[72] Although the Portuguese were familiar with Java's northern coastline and suspected that it was an island, Drake was the first European to navigate the southern shores and to prove that Java was not part of the continent of Terra Australis.[70]

On 24 March Drake sailed off and caught a good wind, and next entered the Indian Ocean; he had roughly 11,000 miles to go before he reached England.[73]

Indian Ocean to Plymouth

Drake had a good wind and without stopping eventually came across the Southern tip of Africa. They rounded the Cape of Good Hope on 15 June where they feared severe storms after reading from accounts by Portuguese and Spanish sailors but were surprised on encountering good weather and a decent wind. Sailing North, food and water became desperately short after having sailed nearly 9,700 miles without stopping and with only one man lost.[74] As they continued North they reached the Western tip of West Africa (present day Sierra Leone) and landed on 22 July taking on fresh water, fruit and provisions. For almost all of the crew they encountered elephants for the first time and an 'oyster-tree', which had no leaves on it, but multitudes of oysters. They were also able to repair the ship, and once done left two days later heading for the English Channel.[75]

Drake and his crew had a few concerns on their return approach to England—namely, that King Philip of Spain may have declared war as a result of Drake's actions, or that Mary Stuart may have become Queen via Elizabeth's death or deposal. Drake aimed to encounter English merchant vessels to gather information before he finally entered port.[70]

Drake arrived in the English Channel on 26 September and soon came across some fishermen, asking them about who was on the throne and if England was at peace.[74] The fisherman informed them that all was well, but they were astonished to learn that the captain was Drake. By this time, most in England had presumed him and his men to be lost, after John Wynter's lone return with the Elizabeth a year prior. The fishermen sailed into Plymouth with Drake and 59 remaining crew aboard, along with the rich cargo of spices and captured Spanish treasures.[76]

Aftermath

Drake became the first Englishman to circumnavigate the globe.[77] Drake however was not the first Englishman to sail the Pacific Ocean; this fell to Magellan's master gunner during the 1519 expedition.[78]

Drake ended up having raided or plundered six coastal towns; he took thirteen ships, plundered them, used them and either released or scuttled them. He ran aground another twelve in Callao.

Elizabeth awarded Drake a knighthood aboard Golden Hind in Deptford on 4 April 1581; the dubbing being performed by a French diplomat, Monsieur de Marchaumont, who was negotiating for Elizabeth to marry the King of France's brother, Francis, Duke of Anjou. By getting the French diplomat involved in the knighting, Elizabeth was gaining the implicit political support of the French for Drake's actions.[79] After receiving his knighthood Drake unilaterally adopted the armorials of the ancient Devon family of Drake of Ash, near Musbury.[80]

The venture raised an enormous amount of money for the nation's coffers. As a result, the Queen declared that all written accounts of Drake's voyages were to become the 'Queen's secrets of the Realm'. In addition Drake and the other participants of his voyages were sworn to their secrecy on the pain of death; she intended to keep Drake's activities away from the eyes of rival Spain. Drake presented the Queen with a jewel token commemorating the circumnavigation. Taken from the Nuestra Señora de la Concepción, it was made of enamelled gold and bore an African diamond and a ship with an ebony hull. For her part, the Queen gave Drake a jewel with her portrait, an unusual gift to bestow upon a commoner, and one that Drake sported proudly in his 1591 portrait by Marcus Gheeraerts now at the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich. The "Drake Jewel", as it is known today, is a rare documented survivor among sixteenth-century jewels; it is conserved at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.[81] As for the rewards, all investors which included Walsingham were rewarded handsomely as individuals who received a return of some 5000 per cent. Some of these men invested in the Levant Company and this led to overseas trade expanding away from the Iberian controlled Indies.[74]

Drake became incredibly rich, and was also allowed to keep £24,000 of the purloined treasure for himself and his crew.[82] He was admired and celebrated by many in England, and became politically powerful – as well as being knighted he quickly became a favourite at the Queens's court. Drake became Mayor of Plymouth in September 1581 and then went on to become a member of parliament in 1581 and 1584. The execution of Doughty nevertheless continued to haunt Drake afterwards. John Doughty, sought legal recourse over the execution of his brother, but the action was dismissed on a technicality.[83]

Drake also had the Queen's blessing to continue his campaign of privateering and the money raised from these raids helped fund the second half of Elizabeth's reign. The Crown lacked sufficient funds to build an efficient navy, but privateering helped subsidised state power by mobilising armed ships and sailors.[84]

The circumnavigation was also a propaganda success that had lasting consequences. The personal stories of the seamen surviving the uncharted perilous waters of the unknown world and the lure of such adventures was an important element in the exploration of trade in the East in the late sixteenth century, which known as the 'Eastern Design'.[85] Thomas Cavendish directly influenced by Drake's voyage set out in 1586 and completed his circumnavigation by 1588. Then other voyages of exploration followed – Ralph Fitch attempted an overland voyage three years after Drake's return, Walter Raleigh in 1595 and James Lancaster in 1591 and 1600 – the latter of whom was one of the founders of the East India Company.[86] Thus began a period of British maritime and colonial dominance that lasted until the 20th century.[87]

Spanish reaction

After Drake's successful voyage, the Spanish now felt vulnerable in their colonies. Francisco de Toledo realised the weakness and wanted to build a series of fortifications on the coast for protection against foreign pirates. He also established 'la Armada del Mar del Sur' (the Southern Fleet) in the port of El Callao.[88] The majority of investment however was for defences and look outs in the Strait of Magellan. In order to seal the passage and having feared they were under English control, Toledo sent a squadron with two ships under Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa not only to explore but also take the region as a possession for Spain. They scrupulously explored the strait, trying to catch out any English they thought were hiding, though none were there. They also surveyed where to build fortifications. Gamboa then directly proceeded to Spain to inform Philip II of the dangers of a seaway open to his European enemies. Once this has been done, approval was given for remedial action and in 1584 an expedition was launched. This however achieved very little, two settlements including Ciudad del Rey Don Felipe were doomed to failure. Gamboa was captured by English privateers two years later.[89]

The biggest repercussion from the voyage however was the relationship between Spain and Portugal; the capture of the Nuestra Señora de la Concepción by Drake proved a shock as it provided evidence that the Spanish had been active in the Far East which had already been a Portuguese concession from the Pope as stated in the 1494 Tordesillas treaty. As a result, this which became one of the reasons for Philip to launch a Spanish invasion of Portugal which led to the Iberian Union.[14]

Drake's two expeditions had increased the annoyance of Philip II, and Anglo-Spanish relations continued to deteriorate, eventually moving towards open war.[2]

War

War between England and Spain officially began in 1585 soon after the execution of Mary Queen of Scots in 1587 and English involvement in the Dutch Revolt. The Queen ordered Drake to lead the next expedition to attack the Spanish New World in a kind of preemptive strike. Drake sailed to the West Indies and in 1586 captured Santo Domingo, Cartagena de Indias and raided St. Augustine. News of this reached Spain and this now further buoyed an invasion of England by Philip.[90]

Philip's project to send an invasion 'Armada' against England soon became known; Drake was to lead yet another preemptive strike on Spanish ships being prepared for it in Cadiz in April 1587. A number were destroyed and the raid, which Drake described as his 'Singeing the King of Spain's Beard' delayed the Armada for a year. This allowed the English to mobilise their defence and Drake was also a leading player during the Armada campaign. Drake's ability to attack England's Catholic enemies made him a hero at home and the terror of the Spanish, who called him 'El Draque' (The Dragon). King Philip put a price some 20,000 ducats for anyone who could eliminate Drake.[91]

Nova Albion claim

The precise location of the port in Nova Albion was carefully guarded to keep it secret from the Spaniards, and several of Drake's maps may have been altered to this end. All first-hand records from the voyage, including logs, paintings and charts, were lost when Whitehall Palace burned in 1698. A bronze plaque inscribed with Drake's claim to the new lands – Drake's Plate of Brass – fitting the description in his account, was discovered in Marin County, California but was later declared a hoax. Now a National Historic Landmark, the officially recognised location of Drake's New Albion is Drakes Bay, California.[92] Some writers have suggested that Queen Elizabeth's desire to maintain secrecy of the locations and extent of Drake's north Pacific explorations led to suppression and obfuscation of the reports.[93] Nevertheless, many of historians, geographers, linguists, anthropologists and other professionals have put forward their ideas of where Drake landed covering the coast from Alaska to northern Mexico.

The claim of Nova Albion occupied a significant place in British geopolitical considerations for centuries and even strengthened Britain's entitlement to the fur trade commerce along the Northwest Coast. Its influential assertions came in the Nootka Crisis with Spain in 1789 and also negotiated the 1846 Oregon Treaty which extended the border of Canada along the 49th parallel to the Pacific.[94]

Legacy

The voyage intrigued the likes of Gerardus Mercator who was often in contact with Abraham Ortelius regarding Drake's discovery of 'Nova Albion', although it was frustrating for them both given the secrecy of Drake's voyage.[74]

The earliest detailed account of the voyage was The World Encompassed by Sir Francis Drake,[95] published in 1628, which was compiled by Drake's nephew, based on his uncle's journal, the notes of Francis Fletcher, and other sources.[96] Nineteenth-century historians had to rely on the vague accounts supplied by Drake's navigator, Nuna da Silva, to the Spanish Viceroy in 1579, and by John Wynter, to the British navy. It was only in 1909 that da Silva's detailed log was discovered in the archives of Seville by Zelia Nuttall.[97] This log gave historians the best insight into Drake's voyage and also what life was like in the Elizabethan Navy.[74]

With the 400th anniversary of the circumnavigation, a replica of the Golden Hind named the Golden Hinde was built starting in 1973. It sailed from Plymouth on her maiden voyage in late the following year, arriving on 8 May 1975 in San Francisco, to commemorate Sir Francis Drake's claiming of New Albion in California.[98]

Drake receives knighthood from Queen Elizabeth. Bronze plaque by Joseph Boehm, 1883, base of Drake statue, Tavistock

Drake receives knighthood from Queen Elizabeth. Bronze plaque by Joseph Boehm, 1883, base of Drake statue, Tavistock Statue commemorating Drake and his circumnavigation of the Globe in Plymouth Hoe

Statue commemorating Drake and his circumnavigation of the Globe in Plymouth Hoe Cross commemorating the landing of Drake, in California in June 1579

Cross commemorating the landing of Drake, in California in June 1579 The stern of the "Golden Hinde" replica of the Golden Hind docked in Southwark

The stern of the "Golden Hinde" replica of the Golden Hind docked in Southwark

In popular culture

The circumnavigation was depicted along with the replica of the Golden Hind in the 1980 film Drake's Venture.

See also

- Magellan expedition

- Loaísa expedition

- Martín Ignacio de Loyola

- George Anson's voyage around the world

- Operation Drake

- Drimys winteri

- A Strange Discovery

References

- Citations

- Lane & Bialuschewski 2019, p. 21

- Wagner 2013, p. 87

- Lytle Schurz, William (1922), "The Spanish Lake", The Hispanic American Historical Review, 5 (2): 181–194, doi:10.1215/00182168-5.2.181, JSTOR 2506024

- "Navegantes europeos en el estrecho de Magallanes [Discovery and recognition of the territory: European navigators in the Strait of Magellan]". Memoria Chilena (in Spanish). Retrieved October 20, 2019.

- Soto Rodríguez, José Antonio (2006). "La defensa hispana del Reino de Chile" (PDF). Tiempo y Espacio (in Spanish). 16. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- Loades 2003, p. 1147

- Bown 2012, pp. 3–5

- Dean 2013, p. 42

- Williams, Neville (1975). The Sea Dogs: Privateers, Plunder and Piracy in the Elizabethan Age. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 116. ISBN 9780297770114.

- Kelsey 2000, p. 66

- Bicheno 2012, p. 133

- Gorrochategui Santos, Luis (2018). English Armada: The Greatest Naval Disaster in English History. Oxford: Bloomsbury. p. 247. ISBN 9781350016996.

- Clarke, Benjamin (1852). The British gazetteer: political, commercial, ecclesiastical, and historical; showing the distances of each place from London and Derby. London: Published (for the proprietors) by H.G. Collins. p. 40.

Vice-Admiral Sir John Wynter knighted by queen elizabeth

- Lindsay 2014, p. 17

- Guasco 2014, p. 98

- Kaufmann, Miranda (2 November 2017). "The Untold Story of How an Escaped Slave Helped Sir Francis Drake Circumnavigate the Globe". History. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- Sugden 2012, p. 61

- Bicheno 2012, pp. 136–137

- Childs 2009, p. 155

- Southwest Pamphlets. 1784. p. 498.

- Sugden 2012, p. 130

- Bicheno 2012, pp. 138–139

- Kelsey 2000, pp. 97–98

- Poole, Reginald Lane; Hunt, William, eds. (1911). The Political History of England: The history of England from the accession of Edward VI to the death of Elizabeth, 1547–1603. Longmans, Green & Company. p. 319.

- Purves, David Laing (1874). The English Circumnavigators: The Most Remarkable Voyages Round the World by English Sailors. William P. Nimmo. p. 53.

- Kelsey 2000, p. 104

- Benson 2015, p. 127

- Barrow, John (1843). The Life, Voyages, and Exploits of Admiral Sir Francis Drake. J. Murray. p. 102. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- Bicheno 2012, pp. 141–142

- Flanagan 2017, p. 94

- Lynch, Robert G.; Spivak, Samuel (2017). Two Voyages to the Pacific Coast of North America: Francis Drake and Brune de Hezeta, Their Voyages Compared with Information about Scurvy. San Francisco: Drake Navigators Guild. p. 37.

- Martinic, Mateo (1977). Historia del Estrecho de Magallanes (in Spanish). Santiago: Andrés Bello. pp. 67–68.

- "Sir Francis Drake: A Pictorial Biography by Hans P. Kraus". Library of Congress. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- Coote 2005, p. 144

- Kelsey 2000, p. 135

- Mitchell 1981, p. 80

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1974). The Southern Voyages 1942–1616. Oxford University Press. p. 651.

- Sugden 2012, p. 125

- Montecino Aguirre, Sonia (2015). Mitos de Chile: Enciclopedia de seres, apariciones y encantos (in Spanish). Catalonia. pp. 196–197. ISBN 9789563243758.

- Spate 2004, p. 251

- Marley 2008, p. 64

- Sugden 2012, p. 126

- Bicheno 2012, p. 144

- Bawlf 2009, p. 141

- Levine & Lane 2015, p. 39

- Coote 2005, p. 157

- Bicheno 2012, p. 146

- Bawlf 2009, pp. 146–147

- Benson 2015, pp. 154–155

- Bundschuh & Alvarado 2012, p. 1257

- Wycherley, George (1935). Buccaneers of the Pacific Volume 1. Rich & Cowan. p. 41.

- Spain in the West, Volume 9. A. H. Clark Company. 1963. pp. 135–136.

- Levine & Lane 2015, p. 42

- Sugden 2012, p. 132

- Bawlf 2009, pp. 360–361

- Sugden 2012, p. 135

- Cassels 2003, pp. 263–264

- Wilson 1998, p. 160

- Fletcher, Francis (1854). The world encompassed by sir Francis Drake, being his next voyage to that to Nombre de Dios. Hakluyt society. pp. 224–225.

- Foster, George McClelland; Beals, Ralph Leon; Heizer, Robert Fleming; Goldschmidt, Walter Rochs (1945). Francis Drake and the California Indians, 1579. University of California Press. p. 12.

- Sugden 2012, pp. 138–139

- Thrower 1984, p. 61

- Dismissed by John Cummins, Francis Drake: The Lives of a Hero 1997:118: "In view of the prominence given in different versions to the crowning of Drake it would be odd if the establishment of a colony had gone unrecorded."

- Levine & Lane 2015, p. 43

- Thrower 1984, pp. 69–70

- Bawlf 2009, pp. 66, 69

- Mason 2018, p. 157

- Andrews 1984, p. 158

- Oakeshott 2010, p. 83

- Sugden 2012, p. 143

- Wilson 1998, pp. 185–186

- Bicheno 2012, p. 151

- Crompton & Goetzmann 2009, pp. 66–67

- Childs 2009, p. 156

- Benson 2015, pp. 169–170

- Thrower 1984, p. 84

- Beding 2016, p. 264

- Sugden 2012, p. 94.

- Perry 1996, p. 182

- Drake, H H. "Drake – The arms of his family and surname: Argent, a waver-dragon gules". GENUKI.

- "The Drake Jewel". Oieahc.wm.edu. Retrieved 2010-02-25.

- Sugden 2012, p. 149

- Senior, W (1921). "Drake at the Suit of John Doughty". Mariner's Mirror. 7 (10): 295. doi:10.1080/00253359.1921.10655051.

- "Queen Elizabeth I's Sea Dogs". The History Press. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- Lawson 2014, p. 4.

- Lawson 2014, p. 2

- Sugden 2012, p. 151

- Zavala, Silvio Arturo, ed. (1975). "Revista de Historia de América" (79–80). Instituto Panamericano de Geografía e Historia: 77.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Bradley 2009, p. 13

- Konstam 2011, pp. 76–77

- Hoffman 1999, p. 1

- "Drake Navigator's Guild". Drakenavigatorsguild.org. 2012-10-17. Retrieved 2012-10-25.

- Ward, Robert (July 1981). "Drake and the Oregon coast: Disputed place in USA". Geographical. Royal Geographical Society. LIII (10): 650.

- Spate 2004, p. 58

- "The World Encompassed by Sir Francis Drake, Being His Next Voyage to That to Nombre de Dios Formerly Imprinted: Carefully Collected out of the Notes of Master Francis Fletcher, Preacher in This Imployment". www.wdl.org. 1628. Retrieved 2020-10-07.

- "The World Encompassed by Sir Francis Drake" (PDF). National Humanities Center.

- Wilson, Derek A. (1977). The world encompassed: Francis Drake and his great voyage. Harper & Row. pp. 212–215. ISBN 9780060146795.

There has always been some confusion about the movements of Drake's ships during the storms of September and October 1578.

- (AP) (10 May 1975). "S.F. Hails Golden Hind". Spokane Daily Chronicle. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

Bibliography

- Andrews, Kenneth (1984). Trade, Plunder and Settlement: Maritime Enterprise and the Genesis of the British Empire, 1480–1630. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521276986.

- Bawlf, Samuel (2009). The Secret Voyage of Sir Francis Drake. D & M Publishers. ISBN 9781926706245.

- Beding, Silvio A, ed. (2016). The Christopher Columbus Encyclopedia. Beding Springer. ISBN 9781349125739.

- Bicheno, Hugh (2012). Elizabeth's Sea Dogs: How England's Mariners Became the Scourge of the Seas. Conway. ISBN 9781844861743.

- Bown, Stephen R. (2012). 1494: How a Family Feud in Medieval Spain Divided the World in Half. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 9781429941303.

- Bradley, Peter (2009). Spain and the Defence of Peru, 1579–1700. Bradley. ISBN 9781409297123.

- Benson, E.F (2015). Sir Francis Drake. Books on Demand. ISBN 9783734004797.

- Bundschuh, Jochen; Alvarado, Guillermo E, eds. (2012). Central America, Two Volume Set: Geology, Resources and Hazards. CRC Press. ISBN 9780203947043.

- Childs, David (2009). Tudor Sea Power: The Foundation of Greatness. Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 9781848320314.

- Coote, Stephen (2005). Drake: The Life and Legend of an Elizabethan Hero. New York: Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 9780743468701.

- Crompton, Samuel Willard; Goetzmann, William H (2009). Francis Drake and the Oceans of the World Explorers of New Lands Series. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 9781438102474.

- Dean, James Seay (2013). Tropics Bound: Elizabeth's Seadogs on the Spanish Main. History Press. ISBN 9780752496689.

- Flanagan, Adrian (2017). The Cape Horners' Club: Tales of Triumph and Disaster at the World's Most Feared Cape. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781472912541.

- Guasco, Michael (2014). Slaves and Englishmen: Human Bondage in the Early Modern Atlantic World. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812223941.

- Hoffman, Paul E (1999). The Spanish Crown and the Defense of the Caribbean, 1535–1585: Precedent, Patrimonialism, and Royal Parsimony. LSU Press. ISBN 9780807124277.

- Kaufmann, Miranda (2017). Black Tudors: The Untold Story. Oneworld Publications. ISBN 9781786071859.

- Kelsey, Harry (2000). Sir Francis Drake: The Queen's Pirate. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300084634.

- Konstam, Angus (2011). The Great Expedition: Sir Francis Drake on the Spanish Main – 1585–86 (Raid). Osprey. ISBN 9781849082457.

- Lane, Kris; Bialuschewski, Arne, eds. (2019). Piracy in the Early Modern Era: An Anthology of Sources. Hackett Publishing. ISBN 9781624668265.

- Lawson, Philip (2014). The East India Company: A History Studies In Modern History. Routledge. ISBN 9781317897651.

- Levine, Robert M; Lane, Kris (2015). Pillaging the Empire: Global Piracy on the High Seas, 1500–1750. Routledge. ISBN 9781317524465.

- Loades, D. M (2003). Reader's Guide to British History, Volume 2. Fitzroy Dearborn. ISBN 9781579582425.

- Lindsay, Ivan (2014). The History of Loot and Stolen Art: from Antiquity until the Present Day. Andrews UK Limited. ISBN 9781906509569.

- Marley, David (2008). Wars of the Americas: A Chronology of Armed Conflict in the Western Hemisphere. ABC CLIO. ISBN 9781598841008.

- Mason, A. E. W (2018). The Life of Francis Drake. Pickle Partners Publishing. ISBN 9781789125771.

- Mitchell, Andrew W, ed. (1981). Operation Drake, Voyage of Discovery. Severn House. ISBN 9780727820075.

- Oakeshott, Walter (2010). Founded Upon the Seas: A Narrative of Some English Maritime and Overseas Enterprises During the Period 1550 to 1616. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781108013420.

- Perry, Maria (1996). The Word of a Prince: A Life of Elizabeth I from Contemporary Documents. Boydell Press. ISBN 9780851156330.

- Spate, Oskar Hermann Khristian (2004). The Spanish Lake. Volume 1 of Pacific since Magellan. ANU E Press. ISBN 9781920942168.

- Sugden, John (2012). Sir Francis Drake. Random House. ISBN 9781448129508.

- Thrower, Norman Joseph William (1984). Sir Francis Drake and the Famous Voyage, 1577–1580: Essays Commemorating the Quadricentennial of Drake's Circumnavigation of the Earth. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520048768.

- Wagner, John (2013). Historical Dictionary of the Elizabethan World: Britain, Ireland, Europe and America. Routledge. ISBN 9781136597619.

- Wilson, Derek (1998). The World Encompassed: Drake's Great Voyage 1577–1580. Allison & Busby. ISBN 9780749003227.

Journals

- Cassels, Sir Simon (August 2003). "Where Did Drake Careen The Golden Hind in June/July 1579? A Mariner's Assessment". The Mariner's Mirror. 89 (1): 260–271. doi:10.1080/00253359.2003.10659292. S2CID 161710358.

External links

- "Queen Elizabeth I's Sea Dogs". History Press. Macmillian Distribution.