Francis Thompson

Francis Joseph Thompson (16 December 1859 – 13 November 1907) was an English poet and Catholic mystic. At the behest of his father, a doctor, he entered medical school at the age of 18, but at 26 left home to pursue his talent as a writer and poet. He spent three years on the streets of London, supporting himself with menial labour, becoming addicted to opium which he took to relieve a nervous problem.

Francis Thompson | |

|---|---|

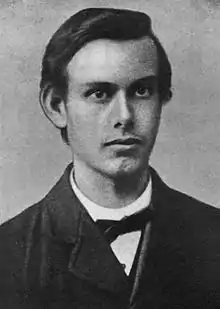

Thompson in 1877. | |

| Born | 16 December 1859 Preston, Lancashire, UK |

| Died | 13 November 1907 (aged 47) |

| Resting place | St. Mary's Cemetery Kensal Green |

| Known for | Ethereal poetry Over 50 poems; essays Hound of Heaven |

In 1888 Wilfrid and Alice Meynell read his poetry and took the opium-addicted and homeless writer into their home for a time, later publishing his first volume, Poems, in 1893. In 1897, he began writing prose, drawing inspiration from life in the countryside, Wales and Storrington. His health, always fragile, continued to deteriorate and he died of tuberculosis in 1907. By that time he had published three books of poetry, along with other works and essays.

Early life and study

Thompson was born in Winckley Street, Preston, Lancashire and baptized four days later in St Ignatius Church. His father, Charles, was a doctor who had converted to Roman Catholicism, following his brother Edward Healy Thompson, a friend of Cardinal Manning. Edward Healy, along with John Costall Thompson, Francis' uncles, were both authors. Francis had a brother who died in infancy, and three younger sisters.[1]

At the age of eleven, Thompson was sent to Ushaw College, a Catholic seminary near Durham. A frail, delicate and extremely shy boy, he was described by his school fellows in 1870 as 'mooney' or abstracted but happy enough. He could be recognised from afar along an 'ambulacrum' or corridor by his habit of sidling sheepishly along the wall with the collar of his coat turned up. Most of his leisure time was spent in the college library where he was fond of history and poetry books. It was noticed that despite the distractions in the library of catapult fights and general mayhem, he had the ability to shut himself off and continue to be absorbed in his reading.[2]

As he advanced up the college he became more skilled at writing and his friends remembered that out of twenty examination essays he obtained first place on sixteen occasions. Once he was punished with a beating for being the last boy to be ready for PE drill. He had no interest in Mathematics and, in his final exam, he came last. The only sport in which he developed an interest was Handball and it is said he achieved a standard above the average. He became a connoisseur of cricket though he rarely participated.[3] In preparation for Ushaw College's centenary celebrations due to take place in 1908, Thompson, by then a celebrated poet, was approached to write a Jubilee Ode to mark the occasion. The poet was delighted that the assignment had been offered to him and it is said that he looked forward to seeing his 'College home' once more. His death, however, in 1907 meant that the commission was never carried out.

Thompson studied medicine for nearly eight years at Owens College, now the University of Manchester. While excelling in essay writing, he took no interest in his medical studies; he had a passion for poetry and for watching cricket matches.[2] He never practised as a doctor, and tried to enlist as a soldier but was rejected for his slightness of stature. Then in 1885 he fled, penniless, to London, where he tried to make a living as a writer, in the meantime taking odd jobs – working for a bootmaker (John McMaster of Panton Street) and booksellers, and selling matches.[3] During this time, he became addicted to opium, which he had first taken as medicine for ill health, having experienced a nervous breakdown while still in Manchester. He lived on the streets of Charing Cross and slept by the River Thames, with the homeless and other addicts. He was turned down by Oxford University, not because he was unqualified, but because of his addiction.[4] Thompson contemplated suicide in his nadir of despair, but was saved from completing the action through a vision which he believed to be that of a youthful poet Thomas Chatterton, who had committed suicide over a century earlier.[5] A prostitute, whose identity Thompson never revealed, befriended him and gave him lodgings. Thompson later described her in his poetry as his saviour.[4]

Writing career

In 1888, after three years on the streets, he was 'discovered' after sending his poetry to the magazine Merrie England. He was sought out by the magazine's editors, Wilfrid and Alice Meynell, who recognised the value of his work. They took him into their home and, concerned about his opium addiction which was at its height following his years on the streets, sent him to Our Lady of England Priory, Storrington, for a couple of years. He continued to take opium but in small doses at irregular intervals, to relieve nerve pain.[4]

Francis wrote most of his poetry during this period from 1888 – 1897, after which he turned to writing prose. He struck up a good relationship with the Meynells who, parents and children, furnished inspiration for some of his poetry. They arranged for publication of his first book Poems in 1893. The book attracted the attention of sympathetic critics in the St James's Gazette and other newspapers, and Coventry Patmore wrote a eulogistic notice in the Fortnightly Review of January 1894. Francis' poem The Hound of Heaven was called by the Bishop of London "one of the most tremendous poems ever written," and by critics "the most wonderful lyric in the language," while the Times of London declared that people will still be learning it 200 years hence. His verse continued to elicit high praise from critics right up to his last volume in 1897. His selected poems published in 1908 contains about 50 pieces in all.[4] Notable among his prose works are an essay on Shelley, "The Life of St. Ignatius", and "Health and Holiness".[3]

Later life and death

Thompson moved around frequently, subsequently living near Pantasaph, Flintshire, in Wales[2] and at Storrington. A lifetime of poverty, ill-health, and opium addiction had taken their toll on him, even though he found success in his last years.

Thompson died from tuberculosis at the age of 47, in the Hospital of St John and St Elizabeth, and is buried in St. Mary's Roman Catholic Cemetery in Kensal Green. His tomb bears the last line from a poem he wrote for his godson, a Meynell: Look for me in the nurseries of Heaven.[1]

Style and influence

His most famous poem, The Hound of Heaven, describes the pursuit of the human person by God. The playwright Eugene O’Neill could recite it from memory.[6]

In 2002, Katherine A. Powers, literary columnist for the Boston Globe, called Hound of Heaven "perhaps the most beloved and ubiquitously taught poem among American Catholics for over half a century," adding that Thompson's other poetry lost its popularity amidst anti-Modernism in the Catholic church during most of the twentieth century. However, she agrees that the dawning century is more akin to his spirit: "His medical training and life on the streets gave him a gritty view of reality and a social conscience, and his governing idea that God is immanent in all things and in all experience, so vexatious to both Victorians and the Vatican alike, no longer strikes an alien or heretical note."[7]

G. K. Chesterton said shortly after his death that "with Francis Thompson we lost the greatest poetic energy since Browning."[8] Among Thompson's devotees was the young J. R. R. Tolkien, who purchased a volume of Thompson's works in 1913–1914, and later said that it was an important influence on his own writing.[9]

Phrases from his poetry have been lifted by others and made famous. The U.S. Supreme Court in Brown II used "with all deliberate speed" for the remedy sought in their famous decision on school desegregation.[10] A phrase in "The Kingdom of God"[11] is the source of the title of Han Suyin's novel A Many-Splendoured Thing. In addition, Thompson wrote the most famous cricket poem, the nostalgic "At Lord's". He also wrote The Poppy (1893), Sister Songs (1895), New Poems (1897), and a posthumously published essay, Shelley (1909).

Halliday Sutherland borrowed the second line of The Hound of Heaven for the title of his 1933 autobiographical best-seller The Arches of the Years.[12] The American novelist Madeleine L'Engle used a line from the poem "The Mistress of Vision" as the title of her last Vicki Austin novel, Troubling a Star. The self-realized poet-yogi, Paramahansa Yogananda, was fond of quoting Thompson's The Hound of Heaven poem,[13]

Bishop Fulton J. Sheen quoted lines from Ex Ore Infantium[14] in his "The True Meaning of Christmas" episode in 1956.[15]

In 2012, Chris Ward's biographical filmscript, Hound: Visions in the Life of the Victorian poet Francis Thompson was staged at the Riverside Studios, Hammersmith and following that the stage version was taken on a tour of London's churches including St Giles-in-the Fields and in St Olav's (City of London) in May 2014.[16] A film of Hound based on the life of Francis Thompson has been made into feature film with a cast including Wayne Sleep, Toyah Willcox and Hazel O'Connor, and with Francis Thompson played by Daniel Hutchinson.[17]

Legacy

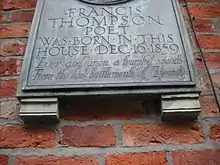

Thompson's birthplace, in Winckley Street, Preston, is marked by a memorial plaque.[18] The inscription reads: "Francis Thompson poet was born in this house Dec 16 1859. Ever and anon a trumpet sounds, From the hid battlements of eternity." The home in Ashton-under-Lyne where Thompson lived from 1864 to 1885 was also marked with a blue plaque. In 2014, however, the building collapsed.[19]

Notes

- Meynell, Everard. "Thompson Francis". Dictionary of National Biography, 1912 Supplement. 3.

- Thomson, John. Francis Thompson, Poet and Mystic, Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent and Company, Limited, 1923

- Chilton, Carroll B. "Francis Thompson." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 14. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1912. 29 November 2022

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Thomson, John (1913). Francis Thompson the Preston-born Poet. London: Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent.

- Brégy, Katherine. "Francis Thompson". The Poets' Chantry.

- McNamara, Pat. "Catholic Poetry", McNamara's Blog, Patheos, November 16, 2013

- "Poet du jour - BCM - Summer 2002". bcm.bc.edu. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- Chesterton, G.K. (1909). "A Dead Poet." In: All Things Considered. New York: John Lane Company, p. 275.

- Tolkien, J.R.R. (1984). The Book of Lost Tales. Edited by Christopher Tolkien. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, p. 29n.

- Chen, James Ming (3 May 2012). "Poetic Justice". SSRN 778884.

- The Kingdom of God at Poets' Corner

- Making the List: A Cultural History of the American Bestseller by Michael Korda. Barnes and Noble Books, 2001. p. 67.

- Yogananda, Paramahansa (1982). "Creating and Destroying Habits at Will," in Man’s Eternal Quest, Self-Realization Fellowship, Los Angeles, CA. ISBN 978-0-87612-233-4.

- "Fifty Christmas Poems for Children: Ex Ore Infantium".

- "The True Meaning of Christmas by Archbishop Fulton Sheen". YouTube.

- "StackPath". indcatholicnews.com. 7 May 2014.

- Hound – via YouTube.

- Good Stuff. "Francis Thompson bronze plaque in Preston". Blue Plaque Places. Archived from the original on 23 November 2015. Retrieved 3 November 2015.

- Dramatic video shows moment dangerous building collapses in Ashton town centre, by John Scheerhout, in the Manchester Evening News; published 27 March 2014; retrieved 19 April 2014

References

- Chisholm, Hugh (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 869.

- Meynell, Everard (1912). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography (2nd supplement). London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Boardman, Brigid M. "Thompson, Francis Joseph (1859–1907)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/36489. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

Further reading

- Abrams, M.H. (1934). The Milk of Paradise: the Effect of Opium Visions on the Works of De Quincey, Crabbe, Francis Thompson, and Coleridge. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- Boardman, Brigid M. (1988). Between Heaven and Charing Cross: The Life of Francis Thompson. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Burdett, Osbert (1925). "Essay in Perspective." In: The Beardsley Period. London: John Lane.

- Butter, Peter H. (1961). Francis Thompson. London: Longmans, Green.

- Breathnach, Caoimhghin S. (1959). "Francis Thompson—Student, Addict, Poet". Journal of the Irish Medical Association. 45: 98–103. PMID 13804081.

- Breathnach, Caoimhghin S. (2008). "Francis Thompson (1859-1907): A Medical Truant and his Troubled Heart". Journal of Medical Biography. 16 (1): 57–62. doi:10.1258/jmb.2006.006075. PMID 18463068. S2CID 24637943.

- Cock, Albert A. (1911). "Francis Thompson," The Dublin Review, Vol. CXLIX, pp. 247–277.

- Figgis, Darrell (1918). "Francis Thompson." In: Bye-ways of Study. Dublin: The Talbot Press ltd., pp. 25–43.

- Hutton, John Alexander (1926). Guidance from Francis Thompson in Matters of Faith. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

- Le Gallienne, Richard (1925). The Romantic '90s. New York: Doubleday, Page & Company.

- Madeleva, Mary (1927). "The Prose of Francis Thompson." In: Chaucer's Nuns, and Other Essays. New York: D. Appleton and Company, pp. 43–88.

- McNabb, Vincent (1935). Francis Thompson & Other Essays. Hassocks: Pepler & Sewell.

- Mégroz, R.L. (1927). Francis Thompson: the Poet of Earth in Heaven. New York: Scribner.

- Meynell, Everard (1926). The Life of Francis Thompson. London: Burns, Oates, & Washbourne.

- Meynell, Viola (1952). Francis Thompson and Wilfrid Meynell: A Memoir. London: Hollis & Carter.

- O'Conor, J.F.X. (1912). A Study of Francis Thompson's Hound of Heaven. New York: John Lane.

- Owlett, F.C. (1936). Francis Thompson. London: J. & E. Bumpus, ltd.

- Reid, J.C. (1959). Francis Thompson, Man and Poet. London: Routledge & Paul.

- Shuster, George N. (1922). "Francis Thompson the Master." In: The Catholic Spirit in Modern English Literature. New York: The Macmillan company, pp. 127–146.

- Walsh, John Evangelist (1967). Strange Harp, Strange Symphony. New York: Hawthorn Books.

External links

- Works by Francis Thompson at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Francis Thompson at Internet Archive

- Works by Francis Thompson at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- A profile by Katharine Tynan in The Fortnightly Review [New Series].

- Boston College Magazine Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- Hound of Heaven (text)

- Francis Thompson Collection at Boston College (text)