Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial

The Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial is a presidential memorial in Washington D.C., dedicated to the memory of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the 32nd President of the United States, and to the era he represents. The memorial is one of two in Washington honoring Roosevelt.

| Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial | |

|---|---|

FDR Memorial sign in 2008 | |

| |

| Location | Washington, D.C., United States |

| Coordinates | 38°53′2″N 77°2′40″W |

| Area | 7.50 acres (3.04 ha) |

| Established | May 2, 1997 |

| Visitors | 3,288,299 (in 2018) |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial |

Dedicated on May 2, 1997 by President Bill Clinton, the national memorial, spread over 7.5 acres (3.0 ha) adjacent to the southwest side of the Tidal Basin along the Cherry Tree Walk in West Potomac Park, traces 12 years of the history of the United States through a sequence of four outdoor rooms, one for each of FDR's terms of office.[1] Sculptures inspired by photographs depict the 32nd president alongside his dog Fala.

Other sculptures depict scenes from the Great Depression, such as listening to a fireside chat on the radio and waiting in a bread line, a bronze sculpture by George Segal. A bronze statue of First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt standing before the United Nations emblem honors her dedication to the UN. It is the only presidential memorial to depict a First Lady.[2]

Considering Roosevelt's disability, the memorial's designers intended to create a memorial that would be accessible to those with various physical impairments. Among other features, the memorial includes an area with tactile reliefs with braille writing for people who are blind. However, the memorial faced serious criticism from disabled activists. Vision-impaired visitors complained that the braille dots were improperly spaced and that some of the braille and reliefs were mounted eight feet off of the ground, placing it above the reach of most people.[3]

Design and features

The memorial's design and development represents the capstone of a distinguished career for the memorial's designer, landscape architect Lawrence Halprin[4] partly because Halprin had fond memories of Roosevelt, and partly because of the sheer difficulty of the task.[5]

Halprin won the competition for the Memorial's design in 1974. However, Congress did not appropriate the funds to move beyond this conceptual stage for more than 20 years.[4] Halprin collaborated with architect Robert Marquis who designed the visitor center in the winning plans.[6]

The memorial's design concept of four outdoor "rooms" and gardens is animated by water, stone, and sculpture.[5] The national memorial now includes sculptures and works by Leonard Baskin, Neil Estern, Robert Graham, Tom Hardy, and George Segal.

Running water is an important physical and metaphoric component of the memorial. Each of the four "rooms" representing Roosevelt's respective terms in office contains a waterfall. As one moves from room to room, the waterfalls become larger and more complex, reflecting the increasing complexity of a presidency marked by the vast upheavals of economic depression and world war.

Tour guides describe the symbolism of the five main water areas as:

- A single large drop – The crash of the economy that led to the Great Depression

- Multiple stairstep drops – The Tennessee Valley Authority dam-building project

- Chaotic falls at varying angles – World War II

- A still pool – Roosevelt's death

- A wide array combining the earlier waterfalls – A retrospective of Roosevelt's presidency

The architecture critic of the Washington Post stated that the memorial was designed "to give people as many options as possible to go this way or that, to reverse directions, to pause, to start over, to be alone, to meet others, and to experience as many different sights, smells and sounds as the site permits."[5]

When the memorial first opened, people were encouraged to wade into the fountains and waterfalls. However, within a matter of days, the National Park Service (NPS), which operates the Memorial, prohibited people from entering the water due to fear of accidents.

The site is a component of the NPS's National Mall and Memorial Parks administrative unit. As a historic area that the NPS manages, the memorial was administratively listed on the National Register of Historic Places on the date of its establishment, May 2, 1997.[7]

Wheelchair depiction

The statue of Franklin Delano Roosevelt stirred controversy over the issue of his disability. Designers decided against plans to have FDR shown in a wheelchair. Instead, the statue depicts the president in a chair with a cloak obscuring the chair, showing him as he appeared to the public during his life. Roosevelt's reliance on a wheelchair was not publicized during his life, as there was a stigma of weakness and instability associated with any disability.[8] However, historians and some disability-rights advocates wanted his disability to be shown for historical accuracy and to tell the story of what they believed to be the source of his strength.[9] Other disability advocates, while not necessarily against showing him in a wheelchair, were wary of protests about the memorial that leaned toward making Roosevelt a hero because of his disability.

The sculptor added casters to the back of the chair in deference to advocates, making it a symbolic "wheelchair". The casters are only visible behind the statue.

The National Organization on Disability, headed by the efforts of Alan Reich, raised US$1.65 million over two years to fund the addition of another statue that clearly showed the president in a wheelchair. In January 2001, the additional statue was placed near the memorial entrance showing FDR seated in a wheelchair much like the one he actually used. The memorial's designer construed the wheelchair controversy as evidence of success: "The most important thing about designing is to generate creativity in others, and to be inclusive – to include the needs and experiences of people interacting with the environment, and to let them be part of its creation."[4]

Gallery

Sign outside of the FDR Memorial in Washington DC

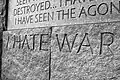

Sign outside of the FDR Memorial in Washington DC "I hate war" inscription.

"I hate war" inscription. View of the Washington Monument from the FDR Memorial.

View of the Washington Monument from the FDR Memorial. Statue of FDR with Fala, his Scottish Terrier

Statue of FDR with Fala, his Scottish Terrier_2011.jpg.webp) Statue of Eleanor Roosevelt in front of the United Nations logo.

Statue of Eleanor Roosevelt in front of the United Nations logo.

Original Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial

During a conversation that he had with Supreme Court Associate Justice Felix Frankfurter in 1941, Roosevelt said that if he were to have a monument in Washington, it should be in front of the National Archives and should be no larger than his desk. A 3-foot (0.9 m) tall, 7-foot (2.1 m) long, 4-foot (1.2 m) wide block of white marble was subsequently dedicated in 1965 as his memorial near the southeast corner of Ninth Street NW and Pennsylvania Avenue NW, within a lawn in front of the National Archives Building.[10] The engraved words on the memorial state: "In Memory of Franklin Delano Roosevelt 1882–1945".[11]

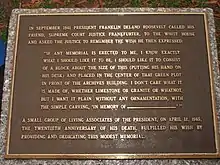

A bronze plaque at the edge of the sidewalk in front of the memorial states:

In September 1941, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt called his friend, Supreme Court Justice Frankfurter, to the White House and asked the Justice to remember the wish he then expressed:

If any memorial is erected to me, I know exactly what I should like it to be. I should like it to consist of a block about the size of this (putting his hand on his desk) and placed in the center of that green plot in front of the Archives Building. I don't care what it is made of, whether limestone or granite or whatnot, but I want it plain without any ornamentation, with the simple carving, "In Memory of ____".A small group of living associates of the President, on April 12, 1965, the twentieth anniversary of his death, fulfilled his wish by providing and dedicating this modest memorial.[11][12]

Further reading

- Halprin, Lawrence (1998). Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial. San Francisco, California: Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-0811817066. LCCN 97001896. OCLC 73511764. Retrieved July 8, 2019 – via Internet Archive.

- Olin, Laurie (2012). "The FDR Memorial Wheelchair Controversy and a 'Taking Part' Workshop Experience". Landscape Journal. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press. 31 (1/2): 183–197. doi:10.3368/lj.31.1-2.183. ISSN 1553-2704. JSTOR 43332537. OCLC 769366501. S2CID 108836482.

- Parsons, John G. (2012). "The Public Struggle to Erect the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial". Landscape Journal. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press. 31 (1/2): 145–159. doi:10.3368/lj.31.1-2.145. ISSN 1553-2704. JSTOR 43332535. OCLC 769366501. S2CID 108764766.

- Rainey, Reuben M. (2012). "The Choreography of Memory: Lawrence Halprin's Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial". Landscape Journal. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press. 31 (1/2): 161–182. doi:10.3368/lj.31.1-2.161. ISSN 1553-2704. JSTOR 43332536. OCLC 769366501. S2CID 108950569.

- Sully, Nicole (2019). "Architecture from the Ouija Board: Louis Kahn's Roosevelt Memorials and the Posthumous Monuments of Modernism". Fabrications: The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand. St. Lucia, Queensland, Australia: University of Queensland Press. 29 (1): 60–85. doi:10.1080/10331867.2018.1540083. ISSN 1033-1867. OCLC 809603466. S2CID 191998111.

See also

- List of statues of Franklin D. Roosevelt

- List of national memorials of the United States

- List of sculptures of presidents of the United States

- History of fountains in the United States

- Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park, New York City; site of another memorial park, opened in 2012.

- Architecture of Washington, D.C.

- Presidential memorials in the United States

References

- "District of Columbia: Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial". The National Parks: Index 2001–2003. Washington, D.C: United States Department of the Interior: National Park Service. 2001. p. 34 – via Internet Archive.

- "The White House / The National Archives". Clinton2.nara.gov. Archived from the original on 2011-09-27. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- Vick, Karl (25 May 1997). "New FDR Statue's Braille Shows a Form of Blindness". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- Sullivan, Patricia. "Lawrence Halprin, 93; Urban projects won wide acclaim for American landscape architect," Washington Post. October 28, 2009.

- Martin, Douglas. "Lawrence Halprin, Landscape Architect, Dies at 93," New York Times. October 28, 2003.

- Kitty Luce; Jessie Durant, eds. (2012). "Robert B. Marquis Collection, c. 1947, 1953-1994" (PDF). Online Archive of California. University of California, Berkeley. p. 6.

- (1) "Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial". National Register of Historic Places: Digital Archive on NPGallery. United States Department of the Interior: National Park Service. Archived from the original on July 8, 2019. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

(2) Bobeczko, Laura L.; Robinson, Judith H. (July 31, 1998). "East and West Potomac Parks Historic District: Revised National Register of Historic Places Nomination" (PDF). Department of the Interior: National Park Service. pp. Section 7, pp. 30–33 (Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 8, 2019. Retrieved July 8, 2019. - "Fdr: Rolling In His Grave???". Raggededgemagazine.com. Retrieved 2013-10-06.

- Mutchler, Meghan (10 April 1995). "Roosevelt's Disability An Issue At Memorial". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 June 2012.

- (1) Kirby, Doug; Smith, Ken; Wilkins, Mike (1996). "Franklin D. Roosevelt Memorial Block: Washington, D.C." RoadsideAmerica.com. Archived from the original on July 8, 2019. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

(2) Coordinates of the original Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial near the National Archives Building: 38°53′37″N 77°01′25″W - W., Kevin (ed.). "'In Memory of Franklin Delano Roosevelt: 1882–1945' marker". HMdb.org: The Historical Marker Database. Archived from the original on July 8, 2019. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- Coordinates of plaque at the edge of the sidewalk in front of the original Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial near the National Archives Building: 38°53′37″N 77°01′25″W