Puffin

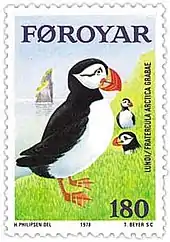

Puffins are any of three species of small alcids (auks) in the bird genus Fratercula. These are pelagic seabirds that feed primarily by diving in the water. They breed in large colonies on coastal cliffs or offshore islands, nesting in crevices among rocks or in burrows in the soil. Two species, the tufted puffin and horned puffin, are found in the North Pacific Ocean, while the Atlantic puffin is found in the North Atlantic Ocean.

| Puffin Temporal range: Pleistocene – Holocene, | |

|---|---|

| Atlantic puffin (F. arctica) with lesser sand eels (Ammodytes tobianus), on Skomer Island | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Charadriiformes |

| Family: | Alcidae |

| Subfamily: | Fraterculinae |

| Tribe: | Fraterculini |

| Genus: | Fratercula Brisson, 1760 |

| Type species | |

| Alca arctica | |

| Species | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Lunda | |

All puffin species have predominantly black or black and white plumage, a stocky build, and large beaks that get brightly colored during the breeding season. They shed the colorful outer parts of their bills after the breeding season, leaving a smaller and duller beak. Their short wings are adapted for swimming with a flying technique underwater. In the air, they beat their wings rapidly (up to 400 times per minute)[1] in swift flight, often flying low over the ocean's surface.

Etymology

The English name "puffin" – puffed in the sense of swollen – was originally applied to the fatty, salted meat of young birds of the unrelated Manx shearwater (Puffinus puffinus), formerly known as the "Manks puffin".[2] Puffin is an Anglo-Norman word (Middle English pophyn or poffin) for the cured carcasses of nestling Manx shearwaters.[3]

Taxonomy

The genus Fratercula was introduced by the French zoologist Mathurin Jacques Brisson in 1760 with the Atlantic puffin (Fratercula arctica) as the type species.[4][5] The name Fratercula is Latin for "friar" from the word fraterculus "little brother",[6] because the puffin's black and white plumage resemble robes worn by monks.[7]

The genus contain three species.[8] The rhinoceros auklet (Cerorhinca monocerata) has sometimes been included in the genus Fratercula,[9] and some authors place the tufted puffin in the genus Lunda.[10] The puffins and the rhinoceros auklet are closely related, together composing the subfamily Fraterculini.[11]

The oldest alcid fossil is Hydrotherikornis from Oregon dating to the Late Eocene while fossils of Aethia and Uria go back to the Late Miocene. Molecular clocks have been used to suggest an origin in the Pacific in the Paleocene.[12] Fossils from North Carolina were originally thought to have been of two Fratercula species,[13] but were later reassigned to one Fratercula, the tufted puffin, and a Cerorhinca species.[14] Another extinct species, Dow's puffin (Fratercula dowi) was found on the Channel Islands of California until the Late Pleistocene or early Holocene.[11]

The Fraterculini are thought to have originated in the Pacific, primarily due to their greater diversity there; there exists only one extant species in the Atlantic, compared to two in the Pacific. This species has shown some significant signs of animal intelligence.[15] On January, 2020, some researchers reported that, Atlantic puffins were seen using sticks as a tool to scratch themselves.[16] The Fraterculini fossil record in the Pacific extends at least as far back as the middle Miocene, with three fossil species of Cerorhinca, and material tentatively referred to that genus, in the middle Miocene to late Pliocene of southern California and northern Mexico. Although there are no records from the Miocene in the Atlantic, a re-examination of the North Carolina material indicated that the diversity of puffins in the early Pliocene was as great in the Atlantic as it is in the Pacific today. This diversity was achieved through influxes of puffins from the Pacific; the later loss of species was due to major oceanographic changes in the late Pliocene due to closure of the Panamanian Seaway and the onset of severe glacial cycles in the North Atlantic.[14]

Extant species

| Species in taxonomic sequence | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Common and binomial names | Image | Description | Range |

| Atlantic puffin (Fratercula arctica) |

.jpg.webp) |

32 cm (13 in) long, with a 53 cm (21 in) wingspan, weight 380 g (13 oz).[17] | North Atlantic: coasts of northern Europe south to northern France, the British Isles, the Faroe Islands, Iceland, Greenland, Norway and Atlantic Canada then south to Maine. Winters south to Morocco and New York[18] |

| Horned puffin (Fratercula corniculata) |

|

38 cm (15 in) long, with a 58 cm (23 in) wingspan, weight 620 g (1.37 lb).[17] | North Pacific: coasts of Siberia, Alaska and British Columbia, wintering south to California and Baja California[19] |

| Tufted puffin or crested puffin[20] (Fratercula cirrhata) |

|

38 cm (15 in) long, with a 63.5 cm (25.0 in) wingspan, weight 780 g (1.72 lb).[17] | North Pacific: British Columbia, throughout southeastern Alaska and the Aleutian Islands, Kamchatka, the Kuril Islands and throughout the Sea of Okhotsk. Winters south to Honshū and California[10] |

Fossils

| Species in taxonomic sequence | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Common and binomial names | Image | Range | |

| Dow's puffin (†Fratercula dowi) |

Channel Islands of California Late Pleistocene | ||

Description

The puffins are stocky, short-winged, and short-tailed birds, with black upper parts and white or brownish-grey underparts. The head has a black cap, the face is mainly white, and the feet are orange-red. The bill appears large and colorful during the breeding season. The colorful outer part of the bill is shed after the breeding season, revealing a smaller and duller true bill beneath.[21] Because of their striking appearance they are also referred to as "clowns of the sea" and "sea parrots".

Although the puffins are vocal at their breeding colonies, they are silent at sea. They fly relatively high above the water, typically 10 m (33 ft) as compared with the 1.6 m (5.2 ft) of other auks.[17]

Behaviour

Breeding

Puffins breed in colonies on coasts and islands; several current or former island breeding sites are referred to as Puffin Island. The male Atlantic puffin builds the nest and exhibits strong nest-site fidelity. Both sexes of the horned puffin help to construct their nest. Horned puffin burrows are usually about 1 meter (3.3 feet) deep, ending in a chamber, while the tunnel leading to a tufted puffin burrow may be up to 2.75 meters (9.0 feet) long. The nesting substrate of the tufted and Atlantic puffins is soft soil, into which tunnels are dug; in contrast, the nesting sites of horned puffins are rock crevices on cliffs.[22] The Atlantic puffin burrow is usually lined with material such as grass, leaves, and feathers but is occasionally unlined. The eggs of the Atlantic puffin are typically creamy white but the occasional egg is tinged lilac.

Where rabbits breed, sometimes Atlantic puffins breed in rabbit burrows.

Puffins form long-term pair bonds or relationships. The female lays a single egg, and both parents incubate the egg and feed the chick (or "puffling").[23][24] The incubating parent holds the egg against its brood patch with its wings. The chicks fledge at night. After fledging, the chicks spend the first few years of their lives at sea, returning to breed about five years later. Puffins in captivity have been known to breed as early as three years of age.

After breeding, all three puffin species winter at sea, usually far from coasts and often extending south of the breeding range.[21]

Iceland is the home to most of the Atlantic puffins with about 10 million individuals.[25] The largest single puffin colony in the world is in the Westmann Isles of Iceland. In 2009, scientists estimated the number of nests to be 1.1 million,[26] and number of individuals there is estimated to be up to 4 million.[25]

Feeding

.jpg.webp)

Like many auks, puffins eat both fish and zooplankton but feed their chicks primarily with small marine fish several times a day. The puffins are distinct in their ability to hold several (sometimes over a dozen) small fish at a time, crosswise in their bill, rather than regurgitating swallowed fish. This allows them to take longer foraging trips since they can come back with more food energy for their chick than a bird that can only carry one fish at a time. This behavior is made possible by the unique hinging mechanism of their beak, which allows the upper and lower biting edges to meet at any of a number of angles.

In 2019, animal experts observed puffins, in two separate geographic locations, using sticks to scratch themselves indicating that the seabirds have a basic ability to use tools.[27][28]

Relationships with humans

Hunting

Puffins are hunted for eggs, feathers, and meat. Atlantic puffin populations drastically declined due to habitat destruction and exploitation during the 19th century and early 20th century. They continue to be hunted in Iceland and the Faroe Islands.[29]

The Blasket Islands off the Irish coast of County Kerry saw a serious decline due to harvesting. Until the islands were abandoned in 1953, the islanders often lived just above starvation level. As a result, the puffins were hunted in large numbers for food.

The Atlantic puffin forms part of the national diet in Iceland, where the species does not have legal protection. Puffins are hunted by a technique called "sky fishing", which involves catching the puffins in a large net as they dive into the sea. Their meat is commonly featured on hotel menus. The fresh heart of a puffin is eaten raw as a traditional Icelandic delicacy.[30] On the small Icelandic island of Grimsey as many as 200 puffins can be caught in a single morning.[31]

Related places and products

The name of the English island Lundy is believed to come from the old Norse word for "puffin island" (Lundey),[32] although an alternative explanation has been suggested with Lund referring to a copse, or wooded area.[33]

The Atlantic puffin is the provincial bird of the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador.

References

- "Puffin FAQs: 26 Questions About Puffins". Project Puffin. National Audubon Society. Archived from the original on 2012-08-29.

- Lockwood, W. B. (1993). The Oxford Dictionary of British Bird Names. Oxford University Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-19-866196-2.

- "Puffin". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- Brisson, Mathurin Jacques (1760). Ornithologie, ou, Méthode Contenant la Division des Oiseaux en Ordres, Sections, Genres, Especes & leurs Variétés (in French and Latin). Paris: Jean-Baptiste Bauche. Vol. 1, p. 52, Vol. 6, p. 81.

- Peters, James Lee, ed. (1934). Check-list of Birds of the World. Vol. 2. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 358.

- Lewis, Charlton T.; Short, Charles (1879). "frātercŭlus". A Latin Dictionary. Perseus Digital Library.

- Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. p. 164. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (2019). "Noddies, gulls, terns, auks". World Bird List Version 9.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- Barrows, Walter Bradford (1877). "Catalogue of the Alcidae contained in the Museum of the Boston Society of Natural History, with a Review and proposed Classification of the Family". Proceedings of the Boston Society of Natural History. 19: 154 – via Biodiversity Heritage Library.

- Harrison 1988, p. 406.

- Guthrie, Daniel A.; Thomas, Howell W.; Kennedy, George L. (1999). "A new species of extinct late Pleistocene puffin (Aves: Alcidae) from the southern California Channel Islands" (PDF). Proceedings of the 5th California Islands Symposium: 525–530.

- Pereira, Sergio L.; Baker, Allan J. (2008). "DNA evidence for a Paleocene origin of the Alcidae (Aves: Charadriiformes) in the Pacific and multiple dispersals across northern oceans". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 46 (2): 430–445. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2007.11.020. PMID 18178108.

- Olson, S. L.; Rasmussen P. (2001) "Miocene and Pliocene birds from the Lee Creek Mine, North Carolina." Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology 90 233-–365.

- Smith, N. A.; Olson, Storrs L.; Clarke, J. A. (2007). "First Atlantic Record of the Horned Puffin genus Cerorhinca (Aves, Alcidae) from the Pliocene of North Carolina" (PDF). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 27 (4): 1039–1042. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[1039:FAROTP]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 13622138.

- Fayet, Annette L.; Hansen, Erpur Snær; Biro, Dora (2019-12-30). "Evidence of tool use in a seabird". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 117 (3): 1277–1279. doi:10.1073/pnas.1918060117. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 6983420. PMID 31889002.

- Tracey, Liz (2020-02-02). "Puffins Seen Using Tools, Breaking Dumb-Puffin Stereotypes". JSTOR Daily. Retrieved 2020-02-02.

- Sibley 2000, pp. 252–253.

- Harrison 1988, p. 404.

- Harrison 1988, p. 405.

- "Tufted Puffin" is the preferred English name. F. Gill and M. Wright, Birds of the World: Recommended English Names, 2006.

- Harrison 1988, pp. 404–406.

- Piatt, John F; Kitaysky, Alexander S. (2002). A. Poole (ed.). "Horned Puffin (Fratercula corniculata)". The Birds of North America Online. Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology. doi:10.2173/bna.603. Retrieved 1 April 2009.

- "Kids patrol to help lost puffins". CBBC. British Broadcasting Corporation. September 3, 2009. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- Enright, Michael (December 30, 2018) [2011]. The Sunday Edition - December 30, 2018 (Radio interview). CBC. Event occurs at 48:00.

- "Safnavefur Vestmannaeyja - Fiska og náttúrugripasafn - Lundi". www.xtreme.is (in Icelandic). Archived from the original on 12 August 2007. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- "Nattsud.is". Archived from the original on 2011-07-22. Retrieved 2010-03-17.

- Andrew, Scottie (31 December 2019). "Two puffins scratched their itches with sticks -- the first evidence that seabirds can use tools". CNN. Retrieved 2020-01-01.

- Fayet, Annette L.; Hansen, Erpur Snær; Biro, Dora (2019-12-24). "Evidence of tool use in a seabird". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 117 (3): 1277–1279. doi:10.1073/pnas.1918060117. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 6983420. PMID 31889002.

- Lowther, Peter E.; Diamond, A. W; Kress, Stephen W.; Robertson, Gregory J.; Russell, Keith (2002). Poole, A. (ed.). "Atlantic Puffin (Fratercula arctica)". The Birds of North America Online. Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology. doi:10.2173/bna.709. Retrieved 1 April 2009.

- Plunkett, John (15 September 2008). "Gordon Ramsay cleared over puffin eating". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 6 April 2009.

- "The island where people eat puffins". BBC News. 24 September 2017. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- "Puffin Island". BBC Radio 4 - The Living World. BBC. Retrieved September 5, 2007.

- "Meaning of lundey". Pete Robson's Lundy Island Site. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved September 5, 2007.

Sources

- Alsop, Fred J. III (2001) "Atlantic Puffin" in: Smithsonian Birds of North America, Western Region: Page 451. New York City: DK Publishing, Inc. ISBN 0-7894-7157-4

- Ehrlich, P.; Dobkin, D. & Wheye, D. (1988) "Atlantic Puffin" in: The Birder's Handbook: a field guide to the natural history of North American birds: 207, 209–214. New York.

- Harrison, Peter (1988). Seabirds. Bromley: Helm. ISBN 0-7470-1410-8.

- Lee, D. S. & Haney, J. C. (1996) "Manx Shearwater (Puffinus puffinus)", in: The Birds of North America, No. 257, (Poole, A. & Gill, F. eds). Philadelphia: The Academy of Natural Sciences, and The American Ornithologists' Union, Washington, DC

- Lockley, R. M. (1953). Puffins. London: J. M. Dent.

- Sibley, David (2000). The North American Bird Guide. Pica Press. ISBN 978-1-873403-98-3.

External links

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 22 (11th ed.). 1911.

- Puffins at the Farne Islands, Northumberland

_with_lesser_sand_eels_(Ammodytes_tobianus).jpg.webp)

-4044.jpg.webp)

-4046.jpg.webp)