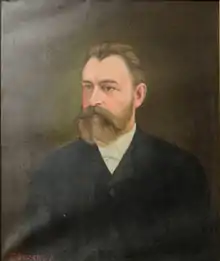

Frederick Augustus Tritle

Frederick Augustus Tritle (August 7, 1833 – November 18, 1906) was an American politician, businessman, and attorney. He served as the sixth Governor of Arizona Territory and held a number of lesser government positions there and in Nevada. He presented the silver spike used at the Promontory Point was held ceremony in May 1869. Tritle was the first governor to have visited Arizona before his appointment and also the first governor to make the territory his lifelong home.[1]

Frederick Augustus Tritle | |

|---|---|

| |

| 6th Governor of Arizona Territory | |

| In office March 8, 1882 – November 2, 1885 | |

| Nominated by | Chester A. Arthur |

| Preceded by | John C. Frémont |

| Succeeded by | C. Meyer Zulick |

| Personal details | |

| Born | August 7, 1833 Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | November 18, 1906 (aged 73) Phoenix, Arizona Territory, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Children | John Stewart Tritle |

| Profession | Attorney |

Background

Tritle was born near Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, to Frederick and Martha (Cooke) Tritle on August 7, 1833. He was educated in his home town and trained to become a lawyer. Tritle was admitted to the bar on April 10, 1855 and moved to Des Moines, Iowa, where he practiced law and engaged in real estate dealings. In 1857 he moved to Council Bluffs, Iowa, where he added a banking business to his other interests. After a short stay in California, Tritle moved to Carson City, Nevada, in February 1860. There he worked as a store clerk and began purchasing mining property.[2]

In 1862, Tritle married Jane Catherine Hereford in Sacramento, California. Jane was born to an influential family and her brother Frank became a U.S. Senator. The couple had four sons and one daughter.[2] In addition to his family, Tritle was active in Freemasonry and the Odd Fellows.[3] He was also an animal lover who adopted many stray dogs during his life.[4]

After his wedding, Tritle and his wife settled in Virginia City, Nevada, where he became president of a mining company. By 1867 he had become president and superintendent of a Comstock Lode operation, the Yellow Jacket Mine. His business interests also extended into railroading, with Tritle helping found the Virginia & Truckee Railroad. In 1869, Tritle was appointed a commissioner overseeing the new transcontinental railroad and later presented Nevada's silver spike during the completion ceremony at Promontory, Utah. Politically, Tritle served in the first session of the Nevada State Senate and lost the 1870 race for Governor of Nevada to Lewis R. Bradley by a vote of 6,149 to 7,200.[3]

Among his activities in Virginia City was operation of a mine stock and bonds brokerage office, Tritle & Murray (partner William B. Murray was from New York and a relative of the wealthy Jerome family). With the decline of the Comstock, in 1879, the partners relocated to Tombstone and began promoting copper and silver mines, eventually acquiring a share of the rich United Verde copper mine at Jerome, Arizona. With his appointment as governor the brokers Tritle & Murray relocated to Prescott, the territorial capital of Arizona.[5]

Governorship

Most details regarding Tritle's appointment as governor are unknown due to the related documentation having been lost.[6] It is known that he had business interests in Arizona by 1880 and advocated the territory's potential prior to his appointment as governor.[7] Following the resignation of John C. Frémont, Tritle was nominated by President Chester A. Arthur as territorial governor on January 26, 1882, confirmed on February 6, and sworn into office on March 8, 1882.[6]

Upon taking office, Tritle faced a problem of lawlessness within the territory caused by outlaw "cowboys" and hostile Indians.[8] To address this issue, the governor proposed creating a group similar to the Texas Rangers to combat the problem. Neither the territorial legislature nor the U.S. Congress were willing to allocate the funds needed to form such a group. Unable to create a group of rangers, Tritle instead called for the formation of volunteer militia to pursue hostile groups of Apache.[9] To combat the loose federation of outlaw Cowboys in Cochise County, General William T. Sherman, following a tour of Arizona's eastern and southern counties, recommended suspension of the Posse Comitatus Act to allow the U.S. Army to aid in restoring order.[10] Based upon the recommendations of Sherman and Tritle, and following consultation with members of the U.S. Senate, President Arthur issued a May 3, 1882 decree threatening to use military force if the criminal element did not disperse.[10] Use of the U.S. Army to enforce the law was not necessary as the outlaw Cowboy problem diminished over the next few months.[11]

Tritle was concerned with the development of Arizona's natural resources. Due to his background, mining was of utmost interest to the governor. Recognizing the potential for timber resources to aid the local economy, he asked the 12th Arizona Territorial Legislature to regulate use of the territory's forests. To aid with water needs, Tritle asked the legislature to appropriate funds for building artesian wells.[12] In addition he recommended that lakes and rivers throughout the territory be stocked with appropriate fish and that railroads connecting the northern and southern sections of the territory be built.[13] To advertise Arizona's potential to easterners, Tritle oversaw the creation of a display at the World Cotton Centennial in New Orleans.[14]

The influx of Mormon settlers to the territory during Tritle's administration caused concerns through the territory. About 2000 Mormon settlers had arrived in Arizona Territory during 1884, raising their totals to 5000 settlers, and their political opponents suspected the LDS Church was trying to create a large enough voting block to take over Arizona (At the time a majority of Idaho's legislature was Mormon and the church had been able to determine Wyoming's delegate to Congress). In response to the influx, five of the settlers were tried and convicted of polygamy.[15] Political response to the convictions was largely favorable, with the New York Times writing, "This is a very good beginning. If there are among the new settlers other men who have violated the law they should be promptly prosecuted and sent to the penitentiary. In no other way can the growth of polygamy in Arizona be checked."[16]

The final major event of Tritle's administration was the 13th Arizona Territorial Legislature, nicknamed the "Thieving Thirteenth". While the governor was never directly linked to any corruption, his association with the session damaged his reputation and caused his popularity to plummet.[17] A petition was even circulated calling for Tritle to be criminally prosecuted for signing off on the session's printing and clerical aid expenses.[18] The sharp drop of popular support was not the reason Tritle left office however. With incoming President Grover Cleveland taking office, Tritle submitted his resignation on October 7, 1885, to allow for a member of the new president's political party to be appointed as governor.[19]

After office

After leaving office, Tritle stayed in Prescott. He was suggested as a candidate for territorial delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1886 and was a delegate to Arizona's 1891 constitutional convention. Beginning in January 1895, Tritle served a two-year term as Yavapai County recorder and was appointed supervisor of the 1900 census within Arizona by President McKinley. Following his work on the census, Tritle's health declined and he moved to Phoenix to live with one of his sons. Tritle died in Phoenix on November 18, 1906, and was given an Episcopalian and Knights Templar funeral.[20] He is buried in Greenwood/Memory Lawn Mortuary & Cemetery in Phoenix. Tritle Peak in the northeast part of Grand Canyon National Park and Mount Tritle in the Bradshaw Mountains south of Prescott are both named for him.[21]

References

- Goff 1978, p. 84.

- Goff 1978, p. 85.

- Goff 1978, p. 87.

- Goff 1978, p. 95.

- Jerome, L. R. (April 14, 1901). "History of the United Verde, The Greatest Mine in the World (3 photos)". Los Angeles Herald, Sunday Magazine. p. 8. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

- Goff 1978, p. 88.

- Wagoner 1970, p. 194.

- Wagoner 1970, pp. 194–5.

- Wagoner 1970, p. 195.

- Wagoner 1970, p. 198.

- Wagoner 1970, p. 200.

- Wagoner 1970, p. 202.

- Wagoner 1970, p. 203.

- Wagoner 1970, p. 204.

- Wagoner 1970, pp. 205–6.

- "Colonies of Polygamists". The New York Times. December 7, 1884. p. 8.

- Wagoner 1970, p. 220.

- Wagoner 1970, pp. 220–1.

- Wagoner 1970, p. 221.

- Goff 1978, p. 94.

- Barnes 1988, p. 451.

- Barnes, Will C. (1988). Arizona place names. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 978-0-8165-1074-0.

- Goff, John S. (1978). Arizona Territorial Officials Volume II: The Governors 1863–1912. Cave Creek, Arizona: Black Mountain Press. OCLC 5100411.

- Wagoner, Jay J. (1970). Arizona Territory 1863–1912: A Political history. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 0-8165-0176-9.